-

Philosophy is for questioning religionPlainly I will agree that such fundamentalism and extremism are abhorrent, but I don't think that makes them nihilistic as such. I mean, kamikaze pilots and jihadi suicide bombers are both motivated by a belief in the afterlife. I abhor those kinds of violent ideology also, but regardless they are not nihilist. 'Nihil' means 'nothing', and nihilism the belief that nothing matters, or that is (ultimately) real. And I don't know if I agree that any of the principle religions hold that humans are 'nothing but dirt'. Twisted and degraded forms of religious belief are not necessarily illustrative of what was originally meaningful about them.

-

MysterianismDoes mysterianism entail that all brains in the universe cannot understand consciousness, or just us? If some superior intellect (machine or biological) could figure out consciousness, it would seem that they could explain it to us in a way we could understand. — RogueAI

What would a solution to the hard problem look like? For that matter, what is the problem? I had thought that the problem is actually a simple one: that you can't produce a third-person account of first-person experience, because the latter includes an experiential dimension that must always be omitted by the objective account. It is basically a rhetorical strategy to demonstrate the limitations of objectivity.

And what would an explanation of consciousness consist of? If the question is 'why does consciousness exist', the most obvious answer is that if it did not, no explanation would be possible, because explanations are only meaningful to conscious subjects such as ourselves (per Descartes' cogito ergo sum).

Consciousness, or 'the mind', is what used to be denoted by the term psyche, which can also be translated as 'soul'. Nowadays 'soul' is said to be a remnant of an earlier age, unilluminated by science, which provides no room for it. And yet..... -

Philosophy is for questioning religionA synoptic reading would be sufficient in my view. I was surprised by how some of the ideas in 'dialectic of enlightenment' resonated never having encountered it earlier in life. I suppose it's a case of 'the enemy of the enemy is a friend'. :-)

-

Philosophy is for questioning religionI've listened to that talk now, and I agree with what he's saying. But thanks for the opportunity of holding forth on one of my favourite themes.

-

Philosophy is for questioning religionBut much of this argument hinges on very specific, expressions or versions of religion. — Tom Storm

It's situated in the context of the Enlightenment criticism of religion, yes. (I was going to add something about the fact that the word 'religion' has no definite meaning, but I thought it might have muddied the waters.)

How could we determine the difference between the purported nihilism of secularism and the potential nihilism of religion? — Tom Storm

What is nihilism? It is variously expressed as the idea that nothing is real, or that nothing has any real meaning. As is well known, Nietszche - I'm not an admirer - forecast that nihilism would be the default condition of Western culture, which had supposedly killed its God. Heidegger likewise believed that the root cause of nihilism was the technological way of thinking that has come to dominate modern society, reducing everything quantifiable facts, and leaving no room for the kinds of intangible values and meanings that are essential to human existence, which he sought to re-articulate in a non-religious framework (albeit many suggest that his concerns and preoccupations remained religious in some sense.)

I noticed another of the critical marxists, Max Horkheimer, had similar concerns. His 1947 book The Eclipse of Reason says that individuals in "contemporary industrial culture" experience a "universal feeling of fear and disillusionment", which can be traced back to the impact of ideas that originate in the Enlightenment conception of reason, as well as the historical development of industrial society. Before the Enlightenment, reason was seen as an objective force in the world. Now, it is seen as a "subjective faculty of the mind". In the process, the philosophers of the Enlightenment destroyed "metaphysics and the objective concept of reason itself." Reason no longer determines the "guiding principles of our own lives", but is subordinated to the ends it can achieve. In other words, reason is instumentalized. Philosophies, such as pragmatism and positivism, "aim at mastering reality, not at criticizing it." (65) Man comes to dominate nature, but in the process dominates other men by dehumanizing them. He forgets the unrepeatable and unique nature of every human life and instead sees all living things as fields of means. His inner life is rationalized and planned. "On the one hand, nature has been stripped of all intrinsic value or meaning. On the other, man has been stripped of all aims except self-preservation." (101) Popular Darwinism teaches only a "coldness and blindness toward nature." (127)

What do you mean by 'the purported nihilism of religion'? -

Philosophy is for questioning religionIsn't the view of mankind as the fortuitous product of theism ... — Tom Storm

It's not fortuitous, but intentional, as a matter of definition.

In Buddhism, the view of 'fortuitous origins' is also rejected, although not in favour of divine creation, but as a form of nihilism. -

Philosophy is for questioning religionI wonder about the sense in which the specifically Enlightenment criticism of religion amounts to the demand for the replacement of the idea of religious revelation with empirical science.

The difficulty with that endeavour is to arrive at any kind of understanding of what the significance and content of such revealed truths might be, especially if they're understood to be beyond the scope of empirical observation and discovery. It might amount to a rejection of the content of such doctrines as a matter of principle, without being ever being able to know exactly what is being rejected.

You could say that Kant attempted to tackle such an analysis in such works as 'Religion within the Limits of Reason', but then even Kant was bound, to some extent, by his particular religious background, which was Lutheran pietism (although the influence of that is contested.)

I notice a recurrent theme in many debates about religious questions is the regular appeal to the purportedly self-evident facts of existence, facts which everyone is said to know and which nobody of sound mind is able to dispute. Implicitly or otherwise, such an appeal is then taken to be an endorsement of scientific method, which is above all seen as a means to elaborate and extend the range and scope of our knowledge of such facts which is surely preferable to the oft-criticized 'belief without evidence', which religious ideas are said to comprise.

But an issue here is the contest between religious lore, containing many symbolic and allegorical depictions of the human condition, on the one hand, with an attitude from which the human subject is altogether removed, or treated exclusively as phenomenon, on par with any other object of analysis (the 'view from nowhere'). And much of that debate is conditioned by the implicit boundary lines required by the rejection of the content of revealed religion, which usually manifests as the commitment to naturalism, defined in terms of its rejection of whatever is held to be supernatural. And by accident of history, that includes a great deal of pre-modern and ancient philosophy as well, insofar as that had become incorporated into the corpus of theology, and rejected along with it - a dialectical process that has unfolded over centuries.

So already there is a kind of asymetry visible in this dynamic. You have on the one side, the confidence of science, which has given rise to the astounding technology which characterises today's world and with which we sorrounded (and even defined), but which situates itself in a universe which it has already declared is devoid of meaning. As various philosophers (including Adorno) have observed, this is associated with the upsurge of nihilism, and the view of mankind as the fortuitous product of chance and physical necessity. As to the alternative, Thomas Nagel, no religious apologist, puts it like this:

To better identify the question, we should start with the religious response. There are many religions, and they are very different, but what I have in mind is common to the great monotheisms, perhaps to some polytheistic religions, and even to pantheistic religions which don’t have a god in the usual sense. It is the idea that there is some kind of all-encompassing mind or spiritual principle in addition to the minds of individual human beings and other creatures – and that this mind or spirit is the foundation of the existence of the universe, of the natural order, of value, and of our existence, nature, and purpose. The aspect of religious belief I am talking about is belief in such a conception of the universe, and the incorporation of that belief into one’s conception of oneself and one’s life.

The important thing for the present discussion is that if you have such a belief, you cannot think of yourself as leading a merely human life. Instead, it becomes a life in the sight of God, or an element in the life of the world soul. You must try to bring this conception of the universe and your relation to it into your life, as part of the point of view from which it is led. This is part of the answer to the question of who you are and what you are doing here. It may include a belief in the love of God for his creatures, belief in an afterlife, and other ideas about the connection of earthly existence with the totality of nature or the span of eternity. The details will differ, but in general a divine or universal mind supplies an answer to the question of how a human individual can live in harmony with the universe. — Thomas Nagel, Secular Philosophy and the Religious Temperament

(See also Does Reason Know what it is Missing, NY Times, Stanley Fish.) -

Why Monism?I suppose the kind of expression I would reach for is that all being is 'cut from the same cloth', so to speak. It's not a numerical unity, an undifferentiated block, which is how it must seem, but that all beings arising from a single source. Of course it's a very difficult thing to articulate and I'm probably not doing a good job of it. I would have to do a search of some of the literature to flesh it out a bit.

-

Why Monism?As I said, I think the basis of monist philosophy is another kind of cognitive mode or way of being. Saying 'all is One' in ordinary discourse is meaningless - as I said above, the only sensible response is 'one what?' So it needs to be understood in the framework of an interpretive model. Why Heidegger came to my mind, I'm not sure, as I'm by no means an expert in his philosophy, but I think he too grasps that this kind of insight requires a different way of being in the world. The point being, there are precedents in philosophy for the idea, but it takes some study to begin to grasp what it means.

-

The circular reasoningphilosophy requires reasoned arguments, true, but truth does not need any proof because it's self-explanatory. And what heaven explains by way of revelation is truth. — Beena

However, you have joined a philosophy forum, and whatever explanations heaven provides to you, and whether they're truthful or not, may not be of any interest to the other participants, if you can see what I mean. -

The circular reasoningJust because some revelation came my way, would i have to prove it? Isn't it self explanatory in its very substance and so needs no proof? — Beena

Philosophy requires reasoned arguments. A revelation may be meaningful to you, but the onus of proof is on you to demonstrate why it ought to be meaningful to anyone else. Or don't say anything about it, but demonstrate what it has taught you by reasoned argument, from premisses to a conclusion. -

Why Monism?. I suppose that today we would call it subjective "Intuition", as opposed to objective "Observation". — Gnomon

I'd question that - it is because it is interpreted through the subject-object perspective that we fail to grasp its import. This interpretation subjectivizes or relativizes insight, making it a personal matter, whereas its import is precisely that it is transpersonal. Many will say that there is 'no intersubjective validation' available for such insights, but that is because today's criteria are generally empirical, recognising only what can be observed and validated by sense-perception.

There's a deep issue at the back of this that is central to my personal quest. It has to do with the emergence of objective consciousness at the basis of the modernity.

I put a question to ChatGPT:

Q: What did Heidegger say about the impact of 'objectification' of consciousness?

A: Heidegger argues that objectification involves reducing the world to a collection of objects that are available for manipulation and control. This way of looking at the world has the effect of distancing us from the world and from our own being. We come to see ourselves and others as objects, and our relationship to the world becomes one of mastery and domination.

According to Heidegger, this way of thinking and relating to the world obscures the true nature of things and leads to the forgetfulness of being. Instead of being attuned to the world and open to its possibilities, we become caught up in a narrow, instrumental way of thinking that limits our understanding and our experience.

Heidegger's solution to this problem involves a return to a more authentic way of being in the world, which he calls "being-toward-death." This involves facing up to the fact of our own mortality and recognizing the finitude and fragility of our existence. By embracing our own mortality and our own vulnerability, we can come to a deeper understanding of ourselves and our relationship to the world.

So 'objectification' is the hallmark of the modern condition and state of consciousness, it's the water we swim in. Whereas the 'unitive vision' occurs in a different register, usually associated with poets, artists and mystics, although it is spoken of by scientists at times, such as an oft-quoted letter from Einstein.

I like the fact that physicists are exploring these ideas. -

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?At least with science, for the most part, we are able to identify regularities and make predictions. — Tom Storm

That's empiricism 101. I think Whitehead was quite aware of that when he wrote the book. I think the point is that empiricism itself always starts with excluding factors that are not under consideration for this or that hypotheses. Those are what Polanyi describes as the boundary conditions of science - the factors that are taken into account at the outset as relevant to the specific subject of the observation or experiment. And they are generally concerned with matters that can be confirmed or disconfirmed by observation and inference. In that sense, religious attitudes which seek to influence empirical outcomes such as praying for someone's recovery or good fortune in the lottery, are easily disconfirmed by straightforward empiricism. But are they the most important or only religious claims that are at issue? What about a maxim such as it being greater to give than to receive, or that one ought to tend to the sick and poor. Are they subject to empirical analysis? There are many others that fall under that general heading. The Dalai Lama once said (in his book on science) that should science show that any of the tenets of Buddhism are empirically invalid, then they should be changed. But so far that hasn't occurred (although for sure many elements of traditional Buddhist cosmology have fallen by the wayside.) -

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?The Buddhist, Parmenidean, Greek, Spinozan and Hegelian ideas that you enumerate...[are] very clearly a faith, not reason, based belief. — Janus

You say that because of your faith in the unerring testimony of the senses. Yet the fact that there might be a woolly mammoth behind a hill (or not) is not sufficient for drawing a conclusion about the overall nature of the human condition.

Alfred North Whitehead argued that faith plays an important role in science. In "Science and the Modern World" (1925), he said that "faith is the foundation of all coherence and stability, and of all progress." He believed that science cannot operate without some basic assumptions or principles that are not themselves subject to empirical verification, and that these assumptions must be taken on faith, that science rests on a metaphysical foundation, which includes beliefs about the nature of reality, causality, and the reliability of sense perception. These metaphysical assumptions are not themselves subject to empirical verification but are instead based on faith in the rationality of the universe and in the ability of human beings to understand it. -

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?Very good. I've not read much of Hannah Arendt though clearly a profound thinker.

As to intellectual intuition, I take it that a proponent would say that it is possible to directly see metaphysical truth. Kant was one of, if not the, first to deny that possibility, the point being that maybe we can, but we cannot demonstrate empirically, logically or discursively that we can, so it remains a matter of belief. I can't see how that can be denied. I can't see any kind of rational argument against it, but I'm open to hearing one. — Janus

I think the kind of 'direct seeing' we're discussing is more characteristic of the mystical traditions. As you know I have huge admiration for Kant, but I can't help but feel something his missing from his rather dessicated account of the a priori, which often amounts to nothing more than competence in mathematics and logic. And also recall that Kant's critique ushered in a novel form of of critical metaphysics, unlike positivism which sought to completely reject it (and which is still very much part of modern discourse).

I'll mention again the essay by Edward Conze on Buddhist philosophy and its European parallels, where he says that in classical philosophy, East and West, there was recognition of an hierarchy of persons, some of whom, through what they are, can know much more than others; that there is a hierarchy also of the levels of reality, some of which are more real, because more exalted, than others; and that the wise have found a wisdom which is true, although it has no empirical basis in observations which can be made by everyone and everybody; and that there is a rare and unordinary faculty in them by which they can attain insight into those domains - through the Prajñāpāramitā of the Buddhists, the logos of Parmenides, the Sophia of the Greeks, Spinoza's amor dei intellectualis, Hegel's Vernunft, and so on; and that true teaching is based on an authority which legitimizes itself by the exemplary life and charismatic quality of its exponents. -

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?Theosophy and such new age stuff and religion more widely sought to find the truth, a description of how things are with regard to the relation between god and the universe and everything. in assuming this could be found it methodological tied itself to what is the case. Science will always do a better job of telling us what is the case. — Banno

'What to do' is bound up with 'how things are' or perhaps more to the point 'what things mean'. Science does a great job of measurement, quantification and prediction, within its scope - not so much on what its discoveries mean (witness the current hand-wringing over predictive AI). Nowadays there are arguments raging in various branches of physics as to whether this or that approach or hypothesis even is science at all. Many of the disputes about interpretations of physics are also philosophical in nature. There you're starting to roam into qualitative judgement with precious little 'inter-subjective agreement' (Google Popperazi ;-) )

When doing Buddhist Studies, one of the Sanskrit terms that leapt out at me was 'yathābhūtaṃ'. This is something like the quality of sagacity. "Yathābhūtaṃ" can be translated as "seeing as it actually is" or "in accordance with reality." It can be used to describe a state of mind or perception that is free from illusions, misunderstandings, or bias, and that allows one to see things objectively and truthfully 1. I suppose there are equivalents in Western languages, perhaps 'Veritas' being one. Arguably, the whole idea of scientific detachment arose from this. But the difference is that post-Galilean science is predicated on the separation of observer from observed, the distinction between primary and secondary qualities, and the divorce of fact and value, among very many other things . This stance amounts to a kind of implicit metaphysic with its baseline assumptions being, as Polanyi said, the boundary conditions for science.

But the over-arching insight characteristic of sagacity arises from a very different kind of mentality or type of consciousness. There are those who say that some of the ancient Greek philosophers - Parmenides and Plotinus come to mind - embodied that kind of sagacity. But then, many of their ideas became assimilated by Christianity and subsequently abandoned on account of that association. And now science has stepped into the vacuum caused by that absence, but without anything like the philosophical depth that they used to embody.

There is no intersubjectively definitive way to determine whether something is the case regarding the veracity of purportedly pure intellectual insights into the nature of things; — Janus

But surely the cultural context is fundamental to that. Our culture does have an agreed basis, and that is scientific method. But the problem, as I mentioned already, is that it methodically excludes the qualitative (not to mention 'the immeasurable'). Different cultures have other standards and frameworks and plenty of scope for intersubjective validation according to those frameworks. Heck, it's practically what 'culture' means. But Western culture, so-called, has an uncanny knack for the dissolution of all and any frameworks. That is what John Vervaeke means by 'the meaning crisis'. I mean, yay science!, computers are great, as is dentistry and penicillin and innummerable other inventions, but the 'scientific worldview' is another matter altogether. But then

the answer to your question may depend on how you define intellectual intuition and what kind of evidence you consider relevant

One of the better, current books I read on this is Defragmenting Modernity, Paul Tyson. -

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?As I tried to point out ealier in this thread, I think the issue is bound up with the emphasis on 'belief' as the sole criteria of what constitutes a religious maxim. This is why I often refer to Eastern philosophical attitude, for their emphasis on insight as distinct from simple acceptance of dogma. Earlier in this thread @Gnomon provided a definition of theosophy, to wit:

Theosophy is a term used in general to designate the knowledge of God supposed to be obtained by the direct intuition of the Divine essence. In method it differs from theology, which is the knowledge of God obtained by revelation, and from philosophy, which is the knowledge of Divine things acquire by human reasoning. . . . India is the home of all theosophic speculation.

There's a problem with that definition, as no Buddhist would agree that illumination comprises 'knowledge of God', as Buddhism is not theistic. But nevertheless the general idea stands, which is that there is genuine insight into the domain of the first cause, etc. It is hard to obtain, and few obtain it, but real nonetheless. But as our view of all such matters is indeed so thoroughly jaundiced by the very dogma which our particular forms of religious consciousness have foisted on us, then it is impossible to differentiate that genuine type of insight from its ossified dogmatic remnants. But, as the sage Rumi said, 'there would be no fools gold, were there no gold'. -

Infinite Regress & the perennial first causePhilosophy is about getting the words right — Banno

That is not the sum total of the subject although it's an important part.

Aristotle's argument for a first cause is based on the observation that motion and change are fundamental features of the natural world and are characteristic of everything that we observe. He believed that motion and change cannot occur without some cause or explanation, and that this cause must itself be unmoved and unchanging. Aristotle argued that if there were no such first cause, then motion and change would be infinite and eternal, without any ultimate explanation or source.

I think part of the reason for his insistence that the first mover must itself be unmoving is derived from the Phaedo. In that, Socrates suggests that in order to explain a particular phenomenon, one must have knowledge of a more general principle or cause that underlies it. Socrates refers to this more general principle as the "cause" or "explanans," and the particular phenomenon as the "effect" or "explanandum."

Socrates asserts that the explanans must be of a higher order than the explanandum, because it is the more general principle that explains why the particular phenomenon occurs. By this logic, if the unmoved mover itself was subject to motion and change, then it would provide no explanation for these, as it would itself be part of what we are required to explain.

So in answer to the question, I don't think Aristotle's principle of the first cause can be equated with the uroboros, and the idea of 'self-causation' in respect to such an analogy is muddled. -

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?The trouble is, while religion pretends to moral authority, it repeatedly fails. — Banno

Someone once told me that all generalisations are false, although I took it with a grain of salt. -

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?"Ritual" simply focuses on a repeating practice or act that ground the mind. It can be used as a purely health-based practice for better mental health in its basic function. — Christoffer

As I noted earlier, Auguste Comte, founder of sociology and of the idea of positivism, attempted to create just such a secular church movement, The Church of Man, although it never really took off. IThere's still a Church of Positivism in Brazil, I read. )

Some will say that religion answers only psychological needs, but that itself is reductionist. According to anthropology and comparative religion, religions operate along a number of different lines to provide social cohesion, normative frameworks, and (most of all) a sense of relatedenss to the cosmos, by providing a mythical story which accords a role to human life in the grand scheme of things.

The difficulty with science replacing religion is that it provides no basis for moral judgements, it is a quantitative discipline concerned chiefly with measurement and formulating mathemtically-sound hypotheses. Strictly speaking there is no 'scientific worldview' as such, as science operates on the basis of tentative (i.e. falsifiable) theories which are only ever approximative. It is a method, and maybe an attitude, rather than a definitive statement as to what is real. (Hence the interminable arguments about 'qualia' and whether human beings actually exist.)

Modern science emerged in the seventeenth century with two fundamental ideas: planned experiments (Francis Bacon) and the mathematical representation of relations among phenomena (Galileo). This basic experimental-mathematical epistemology evolved until, in the first half of the twentieth century, it took a stringent form involving (1) a mathematical theory constituting scientific knowledge, (2) a formal operational correspondence between the theory and quantitative empirical measurements, and (3) predictions of future measurements based on the theory. The “truth” (validity) of the theory is judged based on the concordance between the predictions and the observations. While the epistemological details are subtle and require expertise relating to experimental protocol, mathematical modeling, and statistical analysis, the general notion of scientific knowledge is expressed in these three requirements.

Science is neither rationalism nor empiricism. It includes both in a particular way. In demanding quantitative predictions of future experience, science requires formulation of mathematical models whose relations can be tested against future observations. Prediction is a product of reason, but reason grounded in the empirical. Hans Reichenbach summarizes the connection: “Observation informs us about the past and the present, reason foretells the future.”

The demand for quantitative prediction places a burden on the scientist. Mathematical theories must be formulated and be precisely tied to empirical measurements. Of course, it would be much easier to construct rational theories to explain nature without empirical validation or to perform experiments and process data without a rigorous theoretical framework. On their own, either process may be difficult and require substantial ingenuity. The theories can involve deep mathematics, and the data may be obtained by amazing technologies and processed by massive computer algorithms. Both contribute to scientific knowledge, indeed, are necessary for knowledge concerning complex systems such as those encountered in biology. However, each on its own does not constitute a scientific theory. In a famous aphorism, Immanuel Kant stated, “Concepts without percepts are blind; percepts without concepts are empty.” — Edward Dougherty -

Avoiding blame with 'Physics made me do it' is indefensibleInteresting that stuffy archaic Christianity defends freedom of the will as a matter of principle while scientific materialism views humans as automata.

-

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?Some even question whether Daoism or Buddhism qualify as religions — Janus

Dharma and religion have overlaps but they’re not exactly the same. -

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?Dawkins would denigrate religion as being something like a mind-parasite. It is what he invented the terminology of 'memes' for (which is one of the ideas I actually use, it's a helpful meme.)

One point that is at the back of my mind is the exclusive emphasis on 'belief' in respect of religion. It can be contrasted with the attitude associated with Hindu and Buddhist culture which place more emphasis on the attaining of insight, that being the ostensible aim of meditative practices. But if you go into it, you discover it's really a very difficult path to actually follow. Not that people can't follow it, but there's a lot of room for error and endless scope for self-delusion (traditionally this is why a spiritual master is required, although that requirement is another fertile ground for charlatans and scams)

The founding teacher of Pure Land Buddhism, Shinran, said that the path of meditation and insight was 'the path of sages' - which is, of course, intrinsic to Buddhism, as Buddha and the patriarchs of Buddhism are regarded as sages. But at the same time, Shinran said that very few could actualise that path of insight in reality as it requires exceptional dedication and skill. (You'd never pick that up reading Alan Watts.) The rest of us - 'bombu', in their terms, meaning 'foolish ordinary people' - have to rely wholly and solely on the salvific power of faith in Amida Buddha (one of the legendary Buddhas) who made a vow to bring all beings to Nirvāṇa (it is a school of Mahāyāna Buddhism). Pure Land is, for this reason, often compared with Christianity, which is superficially true although it's vastly different in terms of actual doctrine, which is Buddhist through and through.

There's another level of similarity, though, between the two traditions, which is that the philosophical schools that early Christianity absorbed, such as neoplatonism, and also some of the gnostic sects adjacent to Christianity, likewise taught austere philosophical and contemplative practices with a view to acheiving divine union. In this they were similar to the Buddhist and Hindu schools, as they were all 'axial age' religions (per Karl Jaspers). But the success of Christianity was in rejecting such 'elitism' and its onerous disciplines by offering salvation to all (although on condition of faith in the Doctrine). For this reason, and since the ascendancy of Luther in particular, with his emphasis on salvation by faith alone and sola scriptura, there's almost a complete disconnect between the sapiential or (broadly speaking) gnostic dimension of Christian and Greek philosophy, and how religion is nowadays conceived, as 'belief without evidence'.

The point being, the realisation of higher planes of being, which permeates all of those forms of culture, is 'evidential', in the sense that for those who practice within those cultures, there is said to be the attainment of insight (jñāna or gnosis). Whereas in our technocratic age (and here on this forum) all of that is stereotyped under the umbrella of mere belief. (See Karen Armstrong Metaphysical Mistake)

Is intelligibility itself transcendent? — Tom Storm

The expression "to be, is to be intelligible" is a fundamental concept in Platonism. The phrase refers to the idea that the ultimate reality of the world is not the physical objects that we experience through our senses, but rather the intelligible forms or ideas that objects instantiate.

According to Plato, the material world is constantly changing and imperfect, while Forms are not subject to decay. As such they are the only real objects of knowledge and are what make things in the physical world intelligible or understandable. In other words, the physical objects we see and touch are only shadows or imitations of the perfect Forms, which exist in a realm beyond the physical.

Therefore, when we say that something "is," we mean that it participates in the intelligible Form or idea of that thing. In Platonism, knowledge is the process of understanding the Forms, and the highest form of knowledge is knowledge of the Form of the Good.

The doctrine of forms, modified by Aristotle, became absorbed into theology through Pseudo-Dionysius, Eriugena, Thomas Aquinas and scholastic philosophy, before being generally rejected since the Enlightenment (although neo-thomism and Aristotelianism are making something of a comeback.) -

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?Or is the 'parasite' the human urge to make and hold foundational metanarratives — Tom Storm

Yeah Richard Dawkins would say that. Although he would make an exception for evolutionary biology of course. -

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?That they're parasitic on religion?

Auguste Comte, founder of sociology and inventor of 'positivism', also tried to found a replacement for religion. Comte's religion, which he called the "Religion of Humanity" or the "Religion of Man," was intended to provide a moral framework for a scientific society. It was based on the idea that human beings could achieve happiness and fulfillment by working for the betterment of humanity as a whole, rather than pursuing individual goals or selfish desires. Comte believed that this new religion should be centered around a "cult of humanity," in which the great thinkers, scientists, and social reformers of history would be venerated as saints. He proposed a system of rituals and ceremonies to celebrate the achievements of humanity, including a "Festival of Humanity" to be held on August 20th of each year. It never really took off, although there is still a 'Church of Positivism' in Brazil. -

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?Religious thinking is always hierarchical thinking. — Janus

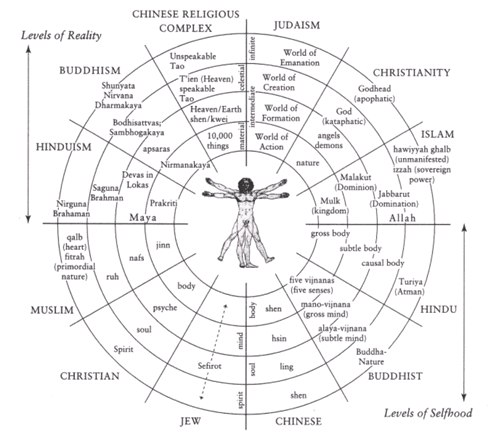

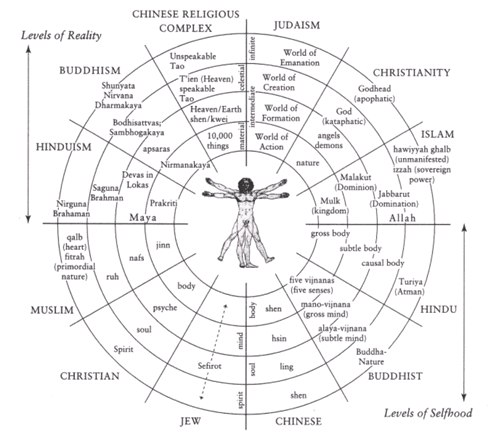

Huston Smith's depiction of the Great Chain of Being -

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?I came into contact with the Theosophical Society through the Adyar Bookshop, which was an institution in Sydney until early in this millennium when it fell victim to Amazon. It was always staffed by kindly older ladies, as was the associated Adyar Library. I noted in my visits there that the membership was on the whole very aged, as the Society’s heyday was in the 1920’s. And it’s been on a downward trajectory ever since. The Victorian Theosophists were an eccentric lot and Madame Blavatsky often depicted as an outrageous charlatan. Nevertheless they were a fascinating milieu, at one stage there was a very well-appointed Theosophy House in the business district of Sydney, and their lectures were well attended. Then there was the discovery and promotion of Krishnamurti, so-called ‘World Teacher’, for whom an amphitheatre was constructed at Balmoral beach in Sydney (which in the end stood vacant, as he famously resigned from the organisation before appearing at it.) I will always retain some affection for them, they are a 'third way' outside of either religion or science as cultural institutions.

-

Replacing matter as fundamental: does it change anything?I wasn’t attempting to trivialize anything. All I meant was that the fact that living beings began to appear on the earth doesn't undermine the idea that consciousness might be concieved as existing as a latency or potentiality in the Universe prior to the appearance of simple organisms, which enable it to manifest, providing a way to conceive of it as a cause, rather than simply as a consequence or epiphenomenon. That writer you told me about, Søren Brier, seems open to that kind of perspective. Agree that may not be an empirical theory at least according to current naturalism. (Incidentally the Life's Ratchet domain name seems to have lapsed although I am aware of the book.)

-

Replacing matter as fundamental: does it change anything?Unlike biosemiosis, it can't pinpoint a moment when the latency became present in the Cosmos — apokrisis

You mean, ‘manifested’. -

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?I will add, science itself has a parallel discipline - the point of the scientific method being to eliminate the personal, the idiosyncratic, the subjective, so as to arrive at a conclusion which does not depend on the observer. It is an austere discipline and its roots are very much entwined with the development of the Western intellectual tradition. But it also assumes at the outset, as one of the 'boundary conditons', as it were, that the domain of enquiry is objective, that it exists totally separately from us. That, I think, is the crucial step that occured with the 'scientific revolution'. Prior to that, in scholastic metaphysics, there remained a sense of the 'unity of knower and known' that is one of the fundamental motifs of the various wisdom traditions. You find it in Aquinas. But with Galileo and the ascendancy of the dualistic model which assigns primary reality to the measurable quantities of objects, then not only do you have a new scientific method, but also a fundamentally different way of being, which we're now so embedded in, that it is very difficult to be aware of it. It's the water in which we all swim.

-

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?do you think I’m making sense in the above things regardless of god, certain values are non-negotiable? — invicta

I think you are, but it's an unwinnable argument, as there will always be counter-examples, such as those @Tom Storm has given.

When I studied Comparative Religion, the very first class was devoted to ‘defining religion’. Convinced this would be a simple task, we all sat around in small groups and canvassed ideas and came up with a list of what we thought would amount to a definition. To our surprise, the lecturer was able to demonstrate that every definition was incomplete or inaccurate. We couldn't, in the end, come up with a definition.

I was (and am) a theosophical type (small t), who believes that the different wisdom traditions portray profound truths, but they are very hard to grasp. They can't be explained in direct terms - that is why so much of their lore is couched in terms of myth, metaphor, and allegory. Ultimately they all demand that you become a different kind of being. Herewith a quote from a Catholic philosopher (I will add, I'm not Catholic)

Our minds do not—contrary to many views currently popular—create truth. Rather, they must be conformed to the truth of things given in creation. And such conformity is possible only as the moral virtues become deeply embedded in our character, a slow and halting process. We have lost the awareness of the close bond that links the knowing of truth to the condition of purity. That is, in order to know the truth we must become persons of a certain sort. The full transformation of character that we need will, in fact, finally require the virtues of faith, hope, and love. And this transformation will not necessarily—perhaps not often—be experienced by us as easy or painless. Hence the transformation of self that we must—by God’s grace—undergo “perhaps resembles passing through something akin to dying.”

You could find exact parallels to that text in Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, and Buddhist sources, were you to look. But it's not the property of any of them, in that it's not confined or limited to them. Let the world get rid of all of them - the requirement would remain. -

A potential solution to the hard problemI think it's essential to it.

As I said in my first comment, the question 'why are we subjects of experience?' is a strange question. It's tantamount to asking 'why do we exist?' The question is asked, 'why did consciousness evolve?' Humphrey quotes another philosopher to that effect:

As far as anybody knows, anything that our conscious minds can do they could do just as well if they weren’t conscious.

For some reason, this strikes me as manifestly absurd. Even very simple critters are conscious - obviously not rationally self-aware and self-conscious - but some level of consciousness is required for them to react to stimuli and survive, to maintain themselves in existence. It's what differentiates organisms from minerals. So the statement is completely self contradictory - 'a conscious mind could do what it does, even without the attribute that makes it "a conscious mind" '. And I don't know that the phenomenon of blindsight is a persuasive argument for that.

But if you phrase the question 'why do I exist?', it is a much more open-ended question than the question of why the brain is configured in such a way as to give rise to the sense of self. The way the question is addressed by Humphrey is from an objective point of view - how to provide a plausible account for the fact that humans and other higher animals have a sense of self, given evolutionary biology and neurology (which, surprise!, is because it provides an incentive to continue existing - which is, after all, the only answer evolutionary biology can give, as continuing to exist is the definition of what constitutes a living species.) But is that all there is to the question of the nature of conscious existence?

David Chalmers discusses Humphrey's earlier work in his book The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory, saying that it fails to address the hard problem of consciousness, suggesting that Humphrey's approach is reductionist and that it relies too heavily on the assumption that consciousness is a mere byproduct of brain function (in other words, assuming what it needs to prove, or begging the question.)

I know that my objection is easily dismissed. The reductionist approach dismisses the whole idea of there being such a problem in the first place! But the question remains whether reductionism has addressed it or whether it's not really seeing it in the first place. (A different kind of blindsight, maybe.) -

A potential solution to the hard problemHow do you view the hard problem as concerned with “what it means to be”? — Luke

As the crux of the issue. Seems to me that Humphries addresses one aspect of the problem - what is the evolutionary rationale for this capacity? Why are humans and other higher animals aware of themselves? It's like 'yes, I can see how the mind produces reflexive awareness of its own inner states'. He talks about the internal systems that allow that, and how it enriches the state of experience, but the rationale for it is evolutionary - how this contributes to our adaptive ability. That's why, I presume, Daniel Dennett posted it, as it dovetails nicely with his evolutionary philosophy, But it doesn't come to terms with the issue of what it means to be - the kind of concerns that animate phenomenology and existentialism. It's a different kind of 'why' - there's an instrumental 'why', and an existential 'why', if you like. I think Humphries addresses the first, but not the second. (Some discussion of this in the comments on the Aeon article, I note.)

I don't want to say that say, what we call "Mars" is constituted (made of) something mental, I don't think it is. But I grant that whatever we know about Mars comes through experience. — Manuel

You're not alone. Albert Einstein was walking with his friend Abraham Pais one afternoon, when he suddenly stopped and said 'Does the moon cease to exist when nobody's looking at it?' He was asking exactly the same question. I won't address it here though as it's a derailer. -

Replacing matter as fundamental: does it change anything?All I ever see is folk saying consciousness is a fundamental simple of the Cosmos, but somehow the complex functional neurology of creatures with evolved nervous systems are needed to get it to the point of being able do stuff that gives evidence it exists. — apokrisis

How about, consciousness is a fundamental simple of experience? Even despite the fact that I comprise billions of cellular operations, many existing on a sub- or un-concious level, nevertheless the fact is I also possess subjective unity of experience. I don't learn about a pain in my foot by being informed of it.

Why do we attribute agency to evolution? Saying that evolution does things or creates things or produces outcomes? When the way natural selection acts is as a filter - it prevents things that are not adaptive from proliferating. Evolution pre-supposes living organisms which adapt and survive, but to say that evolution is the cause of the existence of organisms seems putting the cart before horse. I think there is a tendency to attribute to evolution the agency that used to be assigned to God. It's kind of a remnant of theistic thinking.

As regards consciousness being the product of an evolved nervous system - what about the panpsychist (or maybe even pansemiotic) idea that consciousness is an elemental feature of the Cosmos, that exists in a latent state, and which then manifests itself through evolution. Not that consciousness should be reified as some existing force that can be identified as a separate factor or influence. The lecturer I had in Indian philosophy used to say, 'What is latent, becomes patent'. I'm pretty sure this is conformable with C S Peirce's metaphysics also.

But the idea that it is real as a latency in the cosmos, taking form as organic life, at least addresses:

It is pretty obvious why consciousness is a bigger problem for anyone who thinks it arrived early in the Universe’s evolution. — apokrisis -

A potential solution to the hard problemI believe this misses the main crux of the article. It is not about “building” a sense of self, but about having one — Luke

What occurs to me, reading that article, is that what his model is describing is ego, the self's idea of itself. I don't think it addresses the aspect of the hard problem concerned with what it means to be.

No, by physicalism I mean everything in the world is physical stuff - of the nature of the physical - this means that experience is a wholly physical phenomenon. — Manuel

You could flip this perspective, you know. You're saying that, because we can't define the physical, due to the ambiguous wave-particle nature of matter and the other paradoxes of qm, that it could or must be the case that, if everything exists is physical then the physical must also include the mental. But what if we acknowledged that nothing is completely or only physical, on the grounds that what is physical can never be completely defined, and that what we experience as physical is instead the attribute of a class of cognitive experiences? -

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?Both the Russian and Chinese Communist parties set out to eradicate religion, and to institute 'scientific communism', but both of them failed. (Since the fall of Soviet Communism we now have the appalling spectacle of the officially-sanctioned Russian Orthodox patriarchy blessing Putin's war crimes.) The Chinese Communist Party has made an enormous effort to discourage and control Christian sects within its borders, however it is growing faster there than almost anywhere in the world, from less than a million to more than 100 million in the last four decades.

-

Will Science Eventually Replace Religion?It seems that science is in need of religions’ values, ethics, and morals. Might science absorb values, ethics, and morals from religions? From purified religions, of course. — Art48

One philosophical point to consider in all this is the implication of David Hume's 'is /ought' problem and the difficulty of deriving the latter from the former.

I think one of the implications of his observation is that moral frameworks within which values are oriented are extrinsic to science. As it happens, due to the cultural context within which modern scientific method developed, there is, as it were, a residual moral framework that originated in the broader Christian worldview which had previously characterised Western culture, but such a framework can't be derived from science as such. There are no good or bad chemical reactions, simply things that just happen. And if you want to see what a modern, technologically and scientifically advanced culture that doesn't share the same historical orientation towards human rights is like, look no further than the PRC, where individual rights and social minorities are ruthlessly forced back into the imposed consensus.

One problem is, that 'religion' has itself become a kind of cliché or stereotype, the ossified remnants of myths and motifs that no longer possess vitality or relevance. The culture has outgrown its religious tropes. But think about this: we are surely approaching a period when renunciation ought to be valued because capitalist economics, based on unending growth, are nearing or surpassing their sustainable limits. And within what kind of cultural framework would a renunciate attitude, eschewing material gain and seeking the cultivation of wisdom, make sense?

Here I'm reminded of the famous counter-cultural classic, Small is Beautiful, by E F Schumacher, published in the early 70's on the basis of what he called Buddhist Economics. He believed that conventional Western economics was based on a flawed view of human nature, one that saw people as inherently selfish and materialistic. He believed that this view led to a focus on economic growth and the accumulation of wealth at the expense of other values, such as social justice, environmental sustainability, and spiritual well-being. He argued that Buddhist economics was based on an alternative view of human nature, one that recognized our interdependence with others and with the natural world. He believed that this view led to an economic system that was more equitable, sustainable, and in tune with our spiritual and emotional needs, working with nature rather than against it, and of valuing human relationships and the quality of life over material possessions. It also emphasizes the importance of mindfulness, compassion, and non-violence in economic decision-making.

Fifty years later, not much has come of his ideas, sad to say, but I bring them up, because they embody of kind of religious philosophy, in that the Buddhist worldview still incorporates a soteriology (a doctrine of liberation from the world). And I don't believe that science, or scientific naturalism, offers any such horizon of being, however conceived. (I sometimes wonder if dreams of interstellar colonization represent a kind of sublimated longing for Heaven.) In any case, for a Buddhist commentary on same, I will refer to a lecture given by translator-monk Bhikkhu Bodhi A Buddhist Response to Contemporary Dilemmas of Human Existence. It was a keynote lecture at a conference, so is a dense piece, and quite lengthy, but I find myself in substantial agreement with a lot of it.

The triumph of materialism in the sphere of cosmology and metaphysics had the profoundest impact on human self-understanding. The message it conveyed was that the inward dimensions of our existence, with its vast profusion of spiritual and ethical concerns, is mere adventitious superstructure. The inward is reducible to the external, the invisible to the visible, the personal to the impersonal. Mind becomes a higher order function of the brain, the individual a node in a social order governed by statistical laws. All humankind's ideals and values are relegated to the status of illusions: they are projections of biological drives, sublimated wish-fulfillment. Even ethics, the philosophy of moral conduct, comes to be explained away as a flowery way of expressing personal preferences. Its claim to any objective foundation is untenable, and all ethical judgments become equally valid. The ascendancy of relativism is complete. — Bhikkhu Bodhi

However, I'll also add as a counter to that, that there is a new kind of dialogue emerging between science and spirituality which eschews both religious dogma and scientific materialism, often inspired on the one hand by environmentalism and 'systems science' and even by the idealistic trend arising from 'the new physics':

Sigmund Freud remarked that ‘the self-love of mankind has been three times wounded by science’ referring to the Copernican revolution, Darwin’s discovery of evolution, and Nietszche’s declaration of the Death of God. In a strange way, the Copenhagen Interpretation gave back to humanity what the Enlightenment had taken away, by placing consciousness in a pivotal role in the observational construction of the most fundamental constituents of reality. While this is fiercely contested by what Werner Heisenberg termed ‘dogmatic realism’, for better or for worse it has become an established idea in modern cultural discourse (see e.g. Richard Conn Henry The Mental Universe.)

So the entire field is in a period of intense flux, as it ought to be, considering the tumultous nature of today's world. What is emerging is no longer the hard-edged materialistic science of the later modern period, nor the cliches and time-worn tropes of historical religion, but something that absorbs but exceeds both. -

Why Monism?I mentioned the book The One, by Heinrich Pas, earlier in the thread - see this Aeon essay by the author with a synopsis of some of the ideas in that book. (Also worth taking the time to peruse the reader comments and author responses.)

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum