-

Science seems to create, not discover, reality.What do you think the analogy means? — Janus

It is in a rather curious essay called Law Without Law which you can find here https://m.psychonautwiki.org/w/images/3/30/Wheeler_law_without_law.pdf

Wheeler is well-known for his idea of the participatory universe, that the universe is somehow brought into being by the act of observation (although his definition of ‘observation’ is rather broad as shown below). There’s a well-written magazine article on him here, from which:

While conscious observers certainly partake in the creation of the participatory universe envisioned by Wheeler, they are not the only, or even primary, way by which quantum potentials become real. Ordinary matter and radiation play the dominant roles. Wheeler likes to use the example of a high-energy particle released by a radioactive element like radium in Earth's crust. The particle, as with the photons in the two-slit experiment, exists in many possible states at once, traveling in every possible direction, not quite real and solid until it interacts with something, say a piece of mica in Earth's crust. When that happens, one of those many different probable outcomes becomes real. In this case the mica, not a conscious being, is the object that transforms what might happen into what does happen. The trail of disrupted atoms left in the mica by the high-energy particle becomes part of the real world.

At every moment, in Wheeler's view, the entire universe is filled with such events, where the possible outcomes of countless interactions become real, where the infinite variety inherent in quantum mechanics manifests as a physical cosmos. And we see only a tiny portion of that cosmos. Wheeler suspects that most of the universe consists of huge clouds of uncertainty that have not yet interacted either with a conscious observer or even with some lump of inanimate matter. He sees the universe as a vast arena containing realms where the past is not yet fixed.

I certainly don’t claim to understand everything about it, but it’s interesting, and also very much the kind of science that the OP was about (as I point out in my earlier post.) -

Evolution, creationism, etc?I am not interested in 'why' questions — FreeEmotion

Well, I’ll bow out, then. -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?Mustn’t be forgotten that phenomena are what appears to a subject.

-

Science seems to create, not discover, reality.Yes, and also, don't believe everything you read on the Internet.

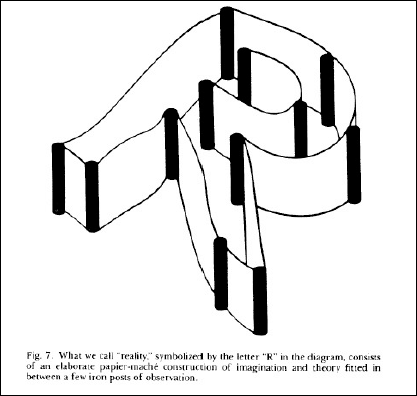

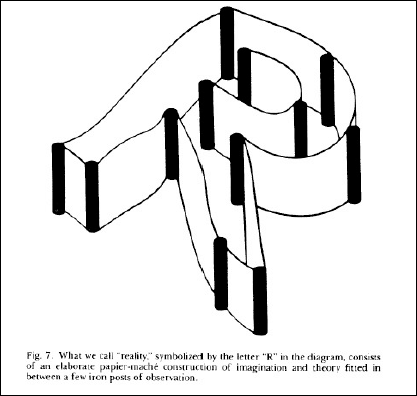

More germane to the actual argument, another graphic I posted previously, from John Wheeler's Law Without Law:

-

Science seems to create, not discover, reality.Just wondering’, you know, given my philosophical proclivities….what kind of answer can one expect when asking about the status of reason? — Mww

I’m vary wary of any attempt to *explain* reason. It seems obvious to most that ‘it evolved’, as above, but I see that as reductionist, in that it reduces reason to a matter of adaptation. That’s why I frequently refer to Thomas Nagel’s essay Evolutionary Naturalism and the Fear of Religion, which is also a defence of the ‘sovereignty of reason’ against naturalistic accounts. -

Science seems to create, not discover, reality.If mind emerges from nature… — Count Timothy von Icarus

Big ‘if’. -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?The quotes are because the term ‘create’ has connotations beyond what is intended in this context. There is no simple way to convey the gist. The basic tenet I’m criticising is the instinctive notion of the mind independence of phenomenal objects.

-

Science seems to create, not discover, reality.No, not saying that. I’m saying that reason is dependent on the ability to abstract, which I don’t think is a controversial claim.

The problem is, naturalism is further up in the epistemological stack that basic reason. So whenever you say that we can understand reason (etc) through neuroscience, you’re the one who is getting it backwards. Notice that naturalism doesn’t explain reason - it doesn’t need to explain it. It can safely assume reason, that there is a repeatable order and things happening for a reason. But as soon as you start to ask ‘why are things like that?’, then you’re into the territory of metaphysics. But then, because there is an inherent bias in naturalism against metaphysics, you’re likely to get into a tangle.

(Sorry for the brevity of the above. It’s Friday night in my Timezone and I’m expected elsewhere.) -

Science seems to create, not discover, reality.I think a more realistic way of looking at it is that human reason is substantially a function of pattern recognition occurring in our brains, and that notions like forms and universals reflect a neurologically naive attempt at making sense of the results of such pattern recognition. — wonderer1

The problem there is that we wouldn’t recognise patterns, let alone have neuroscience, or any science, were it not for the ability to abstract, compare, contrast, equate, and so on. The term ‘intelligible objects’ is indeed unfortunate, as it gives rise to reification (‘making a thing’) but I see ‘object’ as a convenient metaphor for a rational operation. Numbers aren’t actually ‘objects’ in any sense other than ‘the object of thought’. The ability to count, for example, is first and foremost an intellectual act, but the fact that such an act reveals facts which are ‘true in all possible worlds’ suggests the transcendental nature of reason. -

Evolution, creationism, etc?Science accepts evolution because we have a preponderance of evidence of evolution. — flannel jesus

Of course. I mean, duh. But the philosophical question is: why do we exist? Now, evolutionary biology has a clear and unambiguous answer to that question: we exist in order to propagate. There's no reason for that, other than keeping on going. Dawkins says it concisely: 'Why we exist, you're playing with the word "why" there. Science is working on the problem of the antecedent factors that lead to our (biological) existence. Now, "why" in any further sense than that, why in the sense of purpose is, in my opinion, not a meaningful question.' So much for philosophy, eh? Pass the coconut. -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?What's different between what we want to reconcile? — jorndoe

That which is tractable to objective measurement vs qualities of being ("qualia"), which are not.

Your hardcore scientific materialists say on account of this that said qualities of being must be somehow illusory or non-existent.

Check out this paper. Lends some scientific support. -

Evolution, creationism, etc?How do I find out if this argument holds water? I am willing to accept a conclusion either way:

It is confusing to me, on the one hand Michael Behe, a mainstream Biologist with maybe not mainstream views, and those on the other side.

Are they agreed on the facts?

Are they agreed on the conclusions?

Can I tell if they are indeed agreed on facts and how their conclusions differ?

One problem I face is that a lot of the arguments are mixed in with the fine tuning argument. To be clear, my position on the fine tuning argument is this: If the existence of God is not a settled one way or the other, then the fine tuning argument is circumstantial evidence for the existence of a God and Creator, however, it does not conclusively prove anything. Why? Because we are obviously here, despite the odds, as a sort of anthropomorphic argument, and theories could emerge in the future that make the existence of the universe inevitable. It is possible. Conclusive proof is a different thing altogether. — FreeEmotion

Ask a hard question, why don't you. It is a notoriously contentious matter.

If you haven't read Mind and Cosmos by Thomas Nagel, it might be a useful reference. He professes atheism, has no brief for creationism, but the sub-title of the book is 'why neo-darwinian materialism is almost certainly false.' From a purely philosophical perspective he weighs up the big issues.

My own point of view is that I too am opposed to neo-darwinian materialism proposed by the likes of Daniel Dennett, Richard Dawkins and Jerry Coyne. I don't think it holds water philosophically. But I find many of the ID types uncomfortably near to Protestant fundamentalism. It's instructive, for example, that their (now mothballed) site Uncommon Design is adamantly opposed to any idea of 'human-caused climate change' ( I guess because such things are supposed to be God's doing.) It's also instructive that they seem to regard both Edward Feser and David Bentley Hart's classical theological views as being tantamount to atheism - because neither subscribe to the kind of fundamentalist sky-father theology that many American Protestants do. (Hart has nothing but scorn for any kind of ID argument.)

So - very deep issues. I think some of the points Michael Behe and Alvin Plantinga make are quite compelling, but as this is a secular philosophy forum, I would not go into bat for them here. It never ends well.

Physicists pay a good deal of attention to the "Fine Tuning Problem," and it's mentioned in virtually all popular science books on cosmology these days. That's not to say these arguments have convinced people of the need for God to explain the universe, but rather that "there are things we need to explain that we currently cannot." — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think is on the right track. There are a couple of Australian science writers, Luke Barnes and Geraint Lewis who wrote a book The Fortunate Universe (review) which weighs those arguments. They're both mainstream and highly qualified and neither wear their religious convictions too obviously on their sleeve. -

Science seems to create, not discover, reality.:ok:

I can go along with most of that, except for

empirical substrate — Joshs

If the 'empirical substrate' refers to simple cognition, other animals possess that (and as has been shown, some recognise numbers of objects up to a point), but they don't possess the general ability of abstract reason. So I'm not inclined towards a deflationary attitude towards reason.

The power of reason that can produce both the empty universality of mathematical objects and the meaningful sense of real objects is in its anticipative construing of never before seen events in terms of likeness and difference with respect to previous experience, rather than in some ready-made internal capacity to apprehend ready-made external forms. — Joshs

Very close in meaning to the synthetic a priori. And that certain forms seem to pre-exist the minds which discover them is also a relevant consideration. Sure the mind and world are co-arising, but the structures which animate both are commensurable in some sense (which is the contention of classical metaphysics, i.e. Thinking Being, Eric Perl). -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?What we see is a function not simply of what random pixels of shape and color happen to impinge on our retinas. It is a function of what patterns we are able to synthesize out of this chaos of sensation. We have to discern correlations among initially disparate elements of the world, and coordinate these with our own movements. — Joshs

Quite. This is the point of the book I keep referring to, Mind and the Cosmic Order, by Charles Pinter. He shows how this process is working even with studies of insect perception. Minds 'create' the objects of perception, not in the sense that they're otherwise or previously non-existent, but insofar as they're object of cognition (and reason, for us.)

I think that the phenomenology and enactivism that Joshs refers to is aware of this in a way that analytical philosophy is not. -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?To refer to the original context, @Leontiskos was responding to the OP Mind-Created World, but the point that the 'boulder' objection does not address is this one:

there is no need for me to deny that the Universe (or the boulder!) is real independently of your mind or mine, or of any specific, individual mind. Put another way, it is empirically true that the Universe (or boulder) exists independently of any particular mind. But what we know of its existence is inextricably bound by and to the mind we have, and so, in that sense, reality is not straightforwardly objective. It is not solely constituted by objects and their relations. Reality has an inextricably mental aspect, which itself is never revealed in empirical analysis. Whatever experience we have or knowledge we possess, it always occurs to a subject — a subject which only ever appears as us, as subject, not to us, as object. — Wayfarer -

When Does Philosophy Become Affectation?My argument was that boulders treat cracks differently than canyons whether or not and minds are involved: — Leontiskos

My response was to refer to the argumentum ad lapidem, the 'appeal to the stone', by which Samuel Johnson famously attempted to refute Berkeley's argument of the mental nature of reality. In the context in which your argument was made, you failed to address the salient point in question, but proceeded on the mere assumption that 'of course there are mind-independent objects'. -

Science seems to create, not discover, reality.. I see you are saying rationality exists independent of human perception. (A condition of experince but independent of experince. Kant) Can we say this? Could it not be the case that although reason allows us to do things, it's capacity to work is subject entirely to the human point of view. — Tom Storm

I think the traditionalist answer to that is to refer to universals - hence my reference to Russell yesterday. Very briefly, it revolves around the metaphysical assertion that Ideas (whether construed as forms, principles or universals) are only graspable by a rational mind (nous) but they are not produced by the mind. They are 'in the mind, but not of it' - that is, intelligible objects.

It is largely the very peculiar kind of being that belongs to universals which has led many people to suppose that they are really mental. We can think of a universal, and our thinking then exists in a perfectly ordinary sense, like any other mental act. Suppose, for example, that we are thinking of whiteness. Then in one sense it may be said that whiteness is 'in our mind'.....In the strict sense, it is not whiteness that is in our mind, but the act of thinking of whiteness. The connected ambiguity in the word 'idea', which we noted at the same time, also causes confusion here. In one sense of this word, namely the sense in which it denotes the object of an act of thought, whiteness is an 'idea'. Hence, if the ambiguity is not guarded against, we may come to think that whiteness is an 'idea' in the other sense, i.e. an act of thought; and thus we come to think that whiteness is mental. But in so thinking, we rob it of its essential quality of universality. One man's act of thought is necessarily a different thing from another man's; one man's act of thought at one time is necessarily a different thing from the same man's act of thought at another time. Hence, if whiteness were the thought as opposed to its object, no two different men could think of it, and no one man could think of it twice. That which many different thoughts of whiteness have in common is their object, and this object is different from all of them. Thus universals are not thoughts, though when known they are the objects of thoughts. — Bertrand Russell, The World of Universals

Feser makes an identical point:

Consider that when you think about triangularity, as you might when proving a geometrical theorem, it is necessarily perfect triangularity that you are contemplating, not some mere approximation of it. Triangularity as your intellect grasps it is entirely determinate or exact; for example, what you grasp is the notion of a closed plane figure with three perfectly straight sides, rather than that of something which may or may not have straight sides or which may or may not be closed. Of course, your mental image of a triangle might not be exact, but rather indeterminate and fuzzy. But to grasp something with the intellect is not the same as to form a mental image of it. For any mental image of a triangle is necessarily going to be of an isosceles triangle specifically, or of a scalene one, or an equilateral one; but the concept of triangularity that your intellect grasps applies to all triangles alike. Any mental image of a triangle is going to have certain features, such as a particular color, that are no part of the concept of triangularity in general. A mental image is something private and subjective, while the concept of triangularity is objective and grasped by many minds at once. — Edward Feser

In the Aristotelian scheme, nous is the basic understanding or awareness that allows human beings to think rationally. For Aristotle, this was distinct from the processing of sensory perception, including the use of imagination and memory, which other animals can do. For him then, discussion of nous is connected to discussion of how the human mind sets definitions in a consistent and communicable way, and whether people must be born with some innate potential to understand the same universal categories in the same logical ways. — Wikipedia

Broadly speaking, it was the decline of scholastic realism in later medieval thought which leads to today's empiricism, nominalism and materialism - because there is no conceptual space in which there can be real abstractions. That has been collapsed with Scotus' 'univocity of being' and Ockham's nominalism.

That's why I find myself somewhat unwillingly drawn towards neo-Thomism :yikes:

What would Joshs say about the status of reason. — Tom Storm

I would guess he would say it's contingent, as postmodernism generally does. -

Science seems to create, not discover, reality.if rationality emerges from how our mental structures organize and interpret our sensory experiences, leading to consistent and coherent knowledge, then isn't rationality contingent? — Tom Storm

No, because it has to exist in the first place, in order for us to know anything. It's 'transcendental' in Kant's sense that it is implicit in knowledge but not revealed in experience. Accordingly, It's not emergent but pre-supposed.

I think the precursor to that argument is the Argument from Equality in the Phaedo. You will recall that Socrates says that in order to know that two things are exactly equal, we already must possess the idea of equality as the basis for such judgements. I think the principle can be extended to all manner of judgements concerning 'it is', 'it is not', etc. We don't notice that in all such judgements, abstraction is involved. We don't notice it, because judgement relies on it. That is why natural science can't account for reason - because it has already incorporated many such grounding assumptions in its fundamental axioms. That is the source of 'the blind spot of science'. Few see it, and advocating it generally provokes a furious response, which indicates that it's a hot-button issue.

I think the overwhelming tendency in philosophy generally is to vaccilate between 'the world is real' (the objective stance, scientism) and the mind is real (subjective idealism). I think the right balance is to understand that experiential insight has both subjective and objective poles - which is the phenomenological analysis in a nutshell. And even though phenomenology differs from Kant, I still see Kant - and Plato - as the starting point. -

Science seems to create, not discover, reality.Have a read of Mind Created World on Medium (I don't think that needs a log in). The first half is reproduced in a thread of that name.

-

Science seems to create, not discover, reality.If rationality doesn't exist in the world, then the entire scientific project and empiricism is doomed from the outset. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Rationality doesn't exist in the world tout courte. It is derived from the consistency of the relationships between ideas and experiences. (Even ChatGPT agrees!) -

Science seems to create, not discover, reality.If the mind creates the world, did the Moon exist before minds? — Count Timothy von Icarus

Definitely not. But neither did it not exist.

*Nor for transcendental idealism....Whatever judgements are made about the world, the mind provides the framework within which such judgements are meaningful. So though we know that prior to the evolution of life there must have been a Universe with no intelligent beings in it, or that there are empty rooms with no inhabitants, or objects unseen by any eye — the existence of all such supposedly unseen realities still relies on an implicit perspective. What their existence might be outside of any perspective is meaningless and unintelligible, as a matter of both fact and principle.

Hence there is no need for me* to deny that the Universe is real independently of your mind or mine, or of any specific, individual mind. Put another way, it is empirically true that the Universe exists independently of any particular mind. But what we know of its existence is inextricably bound by and to the mind we have, and so, in that sense, reality is not straightforwardly objective. It is not solely constituted by objects and their relations. Reality has an inextricably mental aspect, which itself is never revealed in empirical analysis. Whatever experience we have or knowledge we possess, it always occurs to a subject — a subject which only ever appears as us, as subject, not to us, as object. — Wayfarer

That is from the Mind-Created World OP, and I believe is consistent with Kant's idealism. (Incidentally @Manuel has pointed out an excellent recent book on Kant, Manifest Reality which I think advocates a similar interpretation - the correct one - although I'm still only part-way through it. ) -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?Still not buying the idea of 'build'. But agree with the re-definition according to enactivism.

-

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?But it seems equally the case that humans have been "built" by an external agent — RussellA

As soon as you have to enclose the key word in scare quotes, it's game over ;-)

Unifying investigators of embodied cognition is the idea that the body or the body’s interactions with the environment constitute or contribute to cognition in ways that require a new framework for its investigation - SEP — RussellA

'New' in comparison to what, do you think?

If nature isn't mindless, what kind of mind do you envisage nature having? — RussellA

The kind that manifests where living organisms appear.

Isn't this a lost cause, answering the unanswerable? — RussellA

It can be, but I still find the term 'soul' meaningful, although it's notoriously difficult to define such terms. The Aristotelian approach of the soul being the form of the body - note that 'form' is nothing like 'shape', more like 'organising principle' - rings true to me. -

Evolution, creationism, etc?Does the "Intelligent Design" argument really demonstrate the inadequacy of all versions of theories of evolution proposed so far to explain certain features in organisms — FreeEmotion

They argue that. Whether they succeed in demonstrating it is another matter.

is it necessary to have degree in microbiology to test their arguments? — FreeEmotion

How does one test such an argument? -

CoronavirusFunny that in America at least, the politicians who are the most 'anti-vax', are also the ones most totalitarian leaning.

Or maybe it's not funny. -

The Mind-Created WorldAnd actually, come to think of it, and considering my appalling academic record, it was, until then, about the only exam I'd ever passed.

-

The Mind-Created WorldDon’t know if I’ve related this anecdote but when I finally decided to give uni a shot, several years after leaving school, I sat the quaintly-named Mature Age Student Entrance Exam. It was sat in an old-fashioned exam room, rows of desks, pencil and paper. And Lo and Behold, the main body of the exam was a comprehension test on a 1,500-odd word passage, with searching questions about what it meant. And that passage was from Russell’s Mysticism and Logic! It was spookily apt, as it was just the kind of subject that I was interested in. And not only did it get me in, it more or less defined my self-designed curriculum for my subsequent degree.

-

The Mind-Created WorldThat quote comes from a chapter called The World of Universals in The Problems of Philosophy. It is one of his very early books, but a very helpful treatment of universals in my opinion. As for reconciling universals with naturalism, I don't think he would have tackled that, and I'd be surprised if it were possible, as today's naturalism is pretty solidly grounded in a nominalist attitude, I would have thought. Although I think the early Russell was always more open to some aspects of philosophical idealism than many of his successors and that he was to become later in life.

-

The Mind-Created WorldAnd things imagined by the mind are studied in the field of psychology. — Metaphysician Undercover

Regrettably in this case I have to agree with your opponent. That is the error of psychologism. Geometric shapes and numbers are not mind-dependent in that sense at all, even though they can only be perceived by the mind. As Bertrand Russell remarked of universals 'universals are not thoughts, though when known they are the objects of thoughts.'

These are all created by the imagination, and so is your supposed "object itself", a product of the mind. — Metaphysician Undercover

I imagine you're a steam train or a walrus, so it must be true, right? How could it not be, my imagination cannot err. -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?Do you think there is something it's like to be a Venus Fly Trap? — RogueAI

No, but sure glad not to be the fly :lol: -

Reasons for believing in the permanence of the soul?But if it is the case, there is nothing to be evaluated besides physical objects, and so our view has to default to physicalism, and the self can then never be investigated. — Lionino

Not at all. Recall the primal dictum given to Socrates by the Oracle of the Temple of Delphi: know thyself! But that is a very different matter to knowing about an objective subject, such as physics or chemistry or cosmology. Not that they’re in any way in conflict, but you can be expert in a technical subject yet still lack the insight typically associated with self-knowledge. (I see Hugh Everett III, who came up with the Many Worlds interpretation of QM, as an example.)

Where I place Descartes in the grand scheme of things, is that he is associated with the advent of the modern world-view. Indeed my first undergraduate unit in philosophy was in Descartes: The First Modern Philosopher. Later I came to understand how the combination of Descartes’ philosophy with his co-ordinate geometry, combined with Newtonian science and Galileo’s physics, form one of the pillars of the modern world and the scientific revolution. And obviously it is a momentous cultural and historical achievement. But it also marks the advent of a particularly modern form of consciousness - the self-aware subject situated in the domain of objective forces directed by physical laws. It gives rise to what I have termed ‘the illusion of otherness’, which is the sense of separation between self and world which runs deep in modern culture - whereas in earlier cultures, there is a lived sense of kinship with nature (although not in the romantic sense that modern environmentalism understands it.) So the kind of criticism Husserl makes, is a reflection on Descartes and the human condition. This is why phenomenology becomes one of the main sources of the later existentialism of Heidegger, Sartre and others.

This is basically what I’ve been studying since I was in my twenties and debating here for the last ten years or so. I get it’s a lot to take on and also that I might be mistaken about some fundamental aspects of it. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?But how can my concept of a Thing-in-Itself be more than just its appearance, if by definition it is impossible to conceptualise a Thing-in-Itself outside of its appearance? — RussellA

I think you need to step back and try to re-focus on the basis of this debate. It is that the mind is not a blank slate which passively receives impressions from the world, but an active agent that dynamically constructs the experience of the world ('the world'). The human brain is the most complex natural phenomenon known to science. It works on many levels, from the autonomic, parasympathetic to the unconscious, subconscious and conscious levels (and beyond!) I'll mention again a recent book on cognitive science and philosophy, Mind and the Cosmic Order, by Charles Pinter, which makes the case in the light of current science. I give some details in my OP Mind-Created World.

But the thing is, we can't see that process from the outside. We can't objectify the process, because it is the basis on which objectivity works - it is the process that creates both the object and the subject. And we also can't get outside it in the other sense of seeing the world as it would be in the absence of consciousness. (Yogis and mystics 'go beyond' but I'll leave that aside here).

To put it in one of the quotes I read on this forum (I've since read the book it came from):

Ultimately, what we call “reality” is so deeply suffused with mind- and language-dependent structures that it is altogether impossible to make a neat distinction between those parts of our beliefs that reflect the world “in itself” and those parts of our beliefs that simply express “our conceptual contribution.” The very idea that our cognition should be nothing but a re-presentation of something mind-independent consequently has to be abandoned. — Dan Zahavi, Husserl’s Legacy: Phenomenology, Metaphysics, and Transcendental Philosophy, Dan Zahavi

There is quite a bit of discussion about this idea in current culture, see for example this video Is Reality Real? I'm not endorsing everything in it, but it shows at least how even neurosciencetends to undermine scientific realismis asking these questions.

We could be biological machines. — RussellA

It's an invalid metaphor, as organisms display fundamental characteristics which machines do not. Machines are built by external agents (namely, humans) to perform functions. Organisms do not conform to that description and besides are not created by an external agency to serve a purpose. The mechanist analogy is a hangover from early modern science.

I agree that it may be distasteful to think that humans can be reduced to products of mindless evolution, but does this necessarily mean that this is not the case? — RussellA

That is part of a much larger argument. My view is that the idea of mindless nature is specific to a particular phase of cultural development which was dominant in the late modern period, but which I believe is falling from favour.

How can the soul be beyond the scope of human comprehension as millions of words have been written about it? — RussellA

Kant would say that it's because the mind has a tendency to seek answers to unanswerable questions. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?Why cannot abstract reasoning and language be explained within biology? — RussellA

That's a big question, but again, because biology is the science of living organisms and their environments, their physiology, reproduction, evolution and so on. It's not logic, mathematics or linguistics. I'm familiar with those materials you mention, all of which serve to illustrate the falsity of mechanistic reductionism. All living things, from the very simplest, display intentional behaviours and perform tasks which mechanical devices do not (although they can of course nowadays be modelled in software but again I question the degree to which that could be described as 'mechanical'.) To the extent that we ourselves are biological creatures then we share all of those basic traits with the entire organic kingdom.

But by 'transcending the biological' I mean h. sapiens has capacities and abilities which are beyond those biological functions, amazing though they might be. I see that as having occurred in the process of social development over many hundreds of thousands of years, with the appearance of art, literature, religion, language and story-telling. I think there are many human capacities which have no rationale or even utility from the viewpoint of evolutionary biology (although Dawkins suggests that just as a peacock's tail evolved because it was attractive to peahens, certain memes, like language, spread and evolve because they are attractive or useful to their human hosts. The idea is that language, like a peacock's tail, may have originally arisen for one purpose such as communication but then took on additional roles and became more elaborate, partly due to social selection - that is, being attractive or impressive to other humans. But I see that as reductionist - it reduces culture to a utility in the service of reproduction, or a byproduct of it, rather than having an instrinsic reality. I also include religious consciousness (though not all forms of religious belief or ideology) for which I don't think there is a biological rationale.

I'm using the term 'transcendent' more in the dictionary sense above, although I'm also drawn to the traditionalist idea that reason itself is a higher form of cognition. (This shows through in debates about Platonic realism and the nature of universals, i.e. that man 'the rational animal' is able to grasp through reason principles that are not perceptible to the senses alone and to other creatures.) So I think the attempt to account for human capacities purely through the lens of biological evolution is generally reductionist (see Anything But Human.) Of course I also understand that many people will say 'but what else is there?' as evolution to all intents is the 'secular creation myth'.

Incidentally, as this thread is about Kant, we should mention his distinction between the two terms:

Transcendental: In Kant's philosophy, "transcendental" refers to the conditions that make knowledge possible. It is not about the objects of knowledge themselves but about our mode of knowing those objects prior to the experience of them. Transcendental concepts are a priori, meaning they exist prior to experience. They are necessary conditions for the possibility of experiencing and understanding the world. For example, time and space are transcendental ideas; they are not derived from experience but are the necessary conditions under which any sensory experience can occur.

Transcendent: On the other hand, "transcendent" refers to that which goes beyond the limits of experience and possible knowledge. It deals with things that lie beyond what we can cognitively grasp. In Kant's view, transcendent ideas are those that venture beyond the boundaries of human understanding and into the realm of the unknowable. For instance, the concept of God, the soul, or the totality of the universe are transcendent ideas because they are beyond the scope of empirical investigation and human comprehension. -

Reasons for believing in the permanence of the soul?Now there is something that is interesting. Though it may seem a mistake to objectify the mind, as it is the mind that scans for objects, is it not valid when we talk about self-reflection, or rather, self-analysis? Descartes in his meditations talks about investigating what is this "thinking thing", which is him. Can the memories we have of our mind and/or experiences not be an object which will then be studied by the mind itself? Surely it is not the same thing as a physical body, like a stone, but we could argue that it could be seen as a thing that exists, hence why Descartes calls it a substance. — Lionino

But you're using the word 'thing' and 'existence' very imprecisely here. Surely I can reflect on myself, I can engage in reflection and analysis, but that is always something done by a subject, and the subject itself is never truly an object, as such, except for in the metaphorical sense of 'the object of enquiry'. We relate to the natural world and to others as objects of perception (although understanding of course that others are also subjects), but the 'I' who thus relates is not an object, but that to which or whom objects appear.

I know the following is perhaps tangential to the OP, but recall that this particular digression was based on the quote I mentioned from Descartes which compares stones and minds as instances of substance. I found the reference I was thinking of regarding Husserl's critique of Descartes' tendency to 'objectify' the mind, in the Routledge Introduction to Phenomenology, edited by Dermot Moran. He says:

Of course, Descartes himself had failed to understand the true significance of the cogito and misconstrued it as thinking substance (res cogitans), thus falling back into the old metaphysical habits, construing the ego as a “little tag-end of the world”, naturalising consciousness as just another region of the world, as indeed contemporary programmes in the philosophy of mind deliberately seek to do. ...

(I believe that's a reference to the 20th century program of naturalised epistemology.)

A little further along he says:

Descartes correctly recognised that I exist for myself and am always given to myself in a radically original way. I am a structure of egocogito-cogitatum. According to Husserl, as we have seen, Descartes’s mistaken metaphysical move was to think of this ego as a part of the natural world—as res cogitans, a thinking substance. I am not a part of the world...

Why? because:

In contrast to the outlook of naturalism, Husserl believed all knowledge, all science, all rationality depended on conscious acts, acts which cannot be properly understood from within the natural outlook at all. Consciousness should not be viewed naturalistically as part of the world at all, since consciousness is precisely the reason why there was a world there for us in the first place. For Husserl it is not that consciousness creates the world in any ontological sense—this would be a subjective idealism, itself a consequence of a certain naturalising tendency whereby consciousness is cause and the world its effect—but rather that the world is opened up, made meaningful, or disclosed through consciousness. The world is inconceivable apart from consciousness. Treating consciousness as part of the world, reifying consciousness, is precisely to ignore consciousness’s foundational, disclosive role. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?Kant's references to the "a priori" are explained by what we know today as Innatism, a natural consequence of life's 3.7 billion years of evolution in a dynamic dance with the world of which it is a part. — RussellA

I get the idea that Plato’s appeal to the ‘innate wisdom of the Soul’ can be explained naturalistically with reference to evolutionary psychology. Makes sense, kind of. But that is a Darwinian account of mind, which I think tends towards biological reductionism (in other words, reducing all our faculties to the biological). After all, Darwinian theory is not a theory about the mind, it is a theory about the evolution of species. And evolution is concerned with no other end than successful reproduction.

But no other evolved species has the capacity for abstract reasoning and language in anything more than rudimentary forms. H. Sapiens alone is able to peer into the domain of reason and symbolic form. (Speaking of Chomsky, he co-authored a book on this very question, Why Only Us?, with Robert Berwick.) So my rather more idealist stance is that the human being is able to transcend the biological - that we are more than physical (and therefore more than simply biological). So our cognitive horizons are greater than those of purely sensory creatures. And that is without denying the facts of evolution, although it may be calling what is generally taken as its meaning into question.

Concepts in the mind must refer to something. They cannot be empty terms. — RussellA

I appreciate the care you've taken in your replies. I think the view I’m coming to is that we have nowadays a very restricted view of what is real. You’re saying, ideas must refer to something - they must have a real referent that exists ‘out there somewhere’ as the saying has it. That is what I think Magee is referring to when he wrote "the inborn realism which arises from the original disposition of the intellect". It is what later phenomenology refers to as ’the natural attitude’.

//Incidentally I acknowledge that the above is not directly relevant to Kant per se, although as I've said in the Mind-Created World OP, I believe my philosophy is convergent with Kant's.// -

Reasons for believing in the permanence of the soul?Stanford claims that English "substance" matches Ancient Greek usía in meaning, — Lionino

Via the Latin ‘substantia’, as SEP also says.

Etymology. From Middle English substance, from Old French substance, from Latin substantia (“substance, essence”), from substāns, present active participle of substō (“exist”, literally “stand under”), from sub + stō (“stand”).

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum