-

Best Arguments for PhysicalismIt seems that you are avoiding looking at, whether the following statement of yours is indicative of science denialism.

There is no scientific evidence for physicalism — wonderer1

Because you're not getting the distinction between an empirical theory and a metaphysical stance. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)He’s been a perfectly sound leader as far as I’m concerned notwithstanding all the eye rolling. But rest easy, I won’t argue the case.

-

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?This post outlines why I don’t believe there’s any specific conflict between idealism and science. There’s a conflict between idealism and scientific materialism, but as you’ve already agreed, most scientists don’t push scientific materialism.

-

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?Stop trying to shift the goalposts. :sweat: — 180 Proof

I'm not shifting them. You're just not seeing them :rofl: -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)This issue is so muddled with money for Ukraine and Israel - entirely separate concerns. — jgill

Yeah and who did that muddling, eh? Who was it, exactly, that tied them together. Hint: it wasn't Joe Biden. -

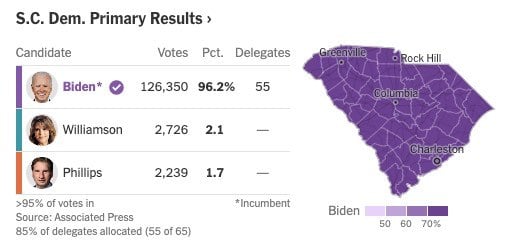

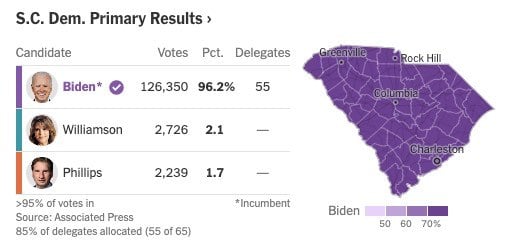

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)

Now THAT'S a majority. The kind of majority Trump felt entitled to in New Hampshire and Iowa (but *didn't* get).

I do hear you on the alarm about undocumented arrivals. It's definitely a serious issue, but again, requires bipartisan support as it's bigger than either party. And that support is being jeopardised by Trump and his congressional minions for purely political reasons. He has no interest in solving it, only in exploiting it. -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?When I don't believe that objections are justified I feel no reason to respond to them.

-

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?Evolution and cosmology were examples pertinent to young earth creationism cases of science denial.

Do you still deny that there is scientific evidence for physicalism? — wonderer1

I regard creationism as on a par with flat-earth theories and the like. It has no merit whatever. But young-earth creationism and anti-scientific ideologies are not typical of mainstream Christianity, and they're certainly not typical of idealism. That you seem to equate them shows a misunderstanding on your part.

As a child, I grew up on the excellent Time-Life series of books on naturalism and evolution, I'm thoroughly versed in evolutionary theory and am interested in paleontology and especially in paleoanthropology. I hadn't been much aware of Biblical creationism until Richard Dawkins started kvetching about it in the early noughties (I grew up in Australia, and creationism has very little presence here. For instance the creationist ideologue, Ken Ham, had to re-locate from Australia to Kentucky to attract an audience.) As for cosmology, I follow that with interest also, you might notice I started a thread on the JWST. I read a fair amount of popular science books and articles. So I don't have any problems with science.

Let's make it clear what 'physicalism' is. Per the SEP entry on same:

Physicalism is, in slogan form, the thesis that everything is physical. The thesis is usually intended as a metaphysical thesis, parallel to the thesis attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Thales, that everything is water, or the idealism of the 18th Century philosopher Berkeley, that everything is mental. The general idea is that the nature of the actual world (i.e. the universe and everything in it) conforms to a certain condition, the condition of being physical. Of course, physicalists don’t deny that the world might contain many items that at first glance don’t seem physical — items of a biological, or psychological, or moral, or social, or mathematical nature. But they insist nevertheless that at the end of the day such items are physical, or at least bear an important relation to (or supervene on) the physical.

That is what I'm disputing. But it doesn't mean that I believe that evolution or the Big Bang didn't occur, or that the Universe is not as science describes it, or other empirical facts. There's no need for me to do that.

Turning to the SEP entry on Idealism, what I argue for is nearer to this:

although the existence of something independent of the mind is conceded, everything that we can know about this mind-independent reality is held to be so permeated by the creative, formative, or constructive activities of the mind (of some kind or other) that all claims to knowledge must be considered, in some sense, to be a form of self-knowledge.

I wouldn't put it exactly like that but it's at least a starting-point (I put it in my terms in the Mind-Created World OP.)

There have been, and are, scientists who are inclined to idealism, and of course many that are not (and probably many more that fall into neither camp.) But neither view is a scientific theory per se. They are metaphysical conjectures or philosophical frameworks.

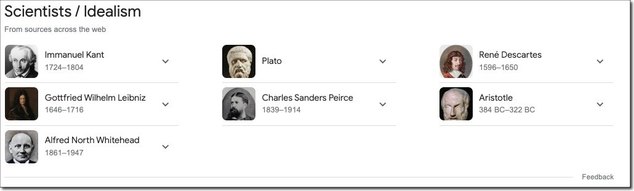

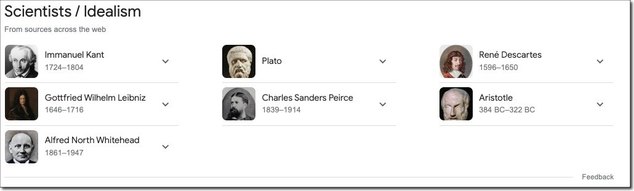

Just for a lark, I googled 'idealist scientists', and look who comes back:

I feel I'm in good company :-) -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)I can tell the difference. — unenlightened

But wouldn't your denunciation apply equally to any plausible candidate to the American Presidency? If if both candidates were to drop out of the race, would you expect anyone to appear who would reverse or atone for what you consider the crimes of the American state? -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?very few philosophers or scientists dogmatically advocate "metaphysical physicalism", you're taking issue wirh a non-issue (or strawman), just barking at shadows in your own little cave, — 180 Proof

Nonsense. Banno frequently cites the surveys of academic philosophy which show that only a minute percentage of them support idealist philosophy. Philosophical and scientific materialism are the de facto belief system in secular culture. And if I were indeed 'barking at shadows' then how come it elicits such volumes of antagonistic cynicism from you?

So, again, please demonstrate how, as you claim, 'the established facts of evolution and cosmology are "equally compatible" with idealism (i.e. antirealism) as they are with physicalism'. — 180 Proof

First please demonstrate why idealism implies anti-realism in the first place.

it is you who are saying I am not allowed to argue — Janus

What I quoted was not an argument, but an angry denunciation.

The truth of spiritual ideas cannot be either empirically or logically demonstrated and hence cannot be rationally argued for. The arguments are always in the form of authority, the idea that there is some special hidden knowledge available only to the elect. — Janus

Again, you're just singing from the positivist playbook

positivism

1.

PHILOSOPHY

a philosophical system recognizing only that which can be scientifically verified or which is capable of logical or mathematical proof, and therefore rejecting metaphysics and theism.

On the Forms.

I don't find the idea of forms at all remote or esoteric. They live on in Aristotelian philosophy and are implicitly part of Western philosophy generally.

Here are examples:

Consider that when you think about triangularity, as you might when proving a geometrical theorem, it is necessarily perfect triangularity that you are contemplating, not some mere approximation of it. Triangularity as your intellect grasps it is entirely determinate or exact; for example, what you grasp is the notion of a closed plane figure with three perfectly straight sides, rather than that of something which may or may not have straight sides or which may or may not be closed. Of course, your mental image of a triangle might not be exact, but rather indeterminate and fuzzy. But to grasp something with the intellect is not the same as to form a mental image of it. For any mental image of a triangle is necessarily going to be of an isosceles triangle specifically, or of a scalene one, or an equilateral one; but the concept of triangularity that your intellect grasps applies to all triangles alike. Any mental image of a triangle is going to have certain features, such as a particular color, that are no part of the concept of triangularity in general. A mental image is something private and subjective, while the concept of triangularity is objective and grasped by many minds at once. — Edward Feser

It is largely the very peculiar kind of being that belongs to universals which has led many people to suppose that they are really mental. We can think of a universal, and our thinking then exists in a perfectly ordinary sense, like any other mental act. Suppose, for example, that we are thinking of whiteness. Then in one sense it may be said that whiteness is 'in our mind'. ...In the strict sense, it is not whiteness that is in our mind, but the act of thinking of whiteness. The connected ambiguity in the word 'idea'...also causes confusion here. In one sense of this word, namely the sense in which it denotes the object of an act of thought, whiteness is an 'idea'. Hence, if the ambiguity is not guarded against, we may come to think that whiteness is an 'idea' in the other sense, i.e. an act of thought; and thus we come to think that whiteness is mental. But in so thinking, we rob it of its essential quality of universality. One man's act of thought is necessarily a different thing from another man's; one man's act of thought at one time is necessarily a different thing from the same man's act of thought at another time. Hence, if whiteness were the thought as opposed to its object, no two different men could think of it, and no one man could think of it twice. That which many different thoughts of whiteness have in common is their object, and this object is different from all of them. Thus universals are not thoughts, though when known they are the objects of thoughts.

We shall find it convenient only to speak of things existing when they are in time, that is to say, when we can point to some time at which they exist (not excluding the possibility of their existing at all times). Thus thoughts and feelings, minds and physical objects exist. But universals do not exist in this sense; we shall say that they subsist or have being, where 'being' is opposed to 'existence' as being timeless. — Bertrand Russell, The Problems of Philosophy - The World of Universals

For Empiricism there is no essential difference between the intellect and the senses. The fact which obliges a correct theory of knowledge to recognize this essential difference is simply disregarded. What fact? The fact that the human intellect grasps, first in a most indeterminate manner, then more and more distinctly, certain sets of intelligible features -- that is, natures, say, the human nature -- which exist in the real as identical with individuals, with Peter or John for instance, but which are universal in the mind and presented to it as universal objects, positively one (within the mind) and common to an infinity of singular things (in the real).

Thanks to the association of particular images and recollections, a dog reacts in a similar manner to the similar particular impressions his eyes or his nose receive from this thing we call a piece of sugar or this thing we call an intruder; he does not know what is sugar or what is intruder. He plays, he lives in his affective and motor functions, or rather he is put into motion by the similarities which exist between things of the same kind; he does not see the similarity, the common features as such. What is lacking is the flash of intelligibility; he has no ear for the intelligible meaning. He has not the idea or the concept of the thing he knows, that is, from which he receives sensory impressions; his knowledge remains immersed in the subjectivity of his own feelings -- only in man, with the universal idea, does knowledge achieve objectivity. And his field of knowledge is strictly limited: only the universal idea sets free -- in man -- the potential infinity of knowledge.

Such are the basic facts which Empiricism ignores, and in the disregard of which it undertakes to philosophize. — Jacques Maritain, The Cultural Impact of Empiricism -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?Am I not allowed to argue for what I believe can and cannot be coherently philosophically investigated? I don't believe things like God, karma, rebirth, heaven and hell can be coherently philosophically investigated on account of the fact that I have never encountered any coherent philosophical investigation of such matters — Janus

If you lived in a culture, such as India or China, where reincarnation was part of the culture, you might have a different view of that. And I suggest you're not interested in any 'coherent philosophical investigation' of such matters because you're pre-disposed to reject consideration of them. Hence your self-appointed role as secular thought police, which we see on display here with tiresome regulariy.

We can know nothing whatsoever about whatever might be "beyond being". The idea is nothing more than the dialectical opposite of 'being'. Fools have always sought to fill the 'domains' of necessary human ignorance with their "knowing". — Janus

Not for nothing Alan Watts' last book was The Book: on the Taboo... And it is a cultural taboo, of that there is no doubt, as one who regularly questions it. -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?the supposition physicalism is only a paradigm, or set of methodological criteria (i.e. working assumptions), for making and interpreting explanatory models of phenomena and, therefore, not "entailed" by modern sciences. — 180 Proof

I agree. Physicalism is supposed for all practical purposes, as physical objects are what methodological naturalism deals with. But that is not physicalism as a metaphysical view. It's physicalism as a metaphysic that I take issue with. That's why I say that @wonderer1 is wrong. He thinks that my philosophical view seeks to dispute the facts of evolution, cosmology etc. I don't dispute the facts. I only dispute that they mean. -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?Although I'm not sure, something along the lines of Wayfarer's suggestion currently seem quite plausible:

My interpretation of 'beyond being' is that it means 'beyond the vicissitudes of existence', 'beyond coming-to-be and passing away'. That idea is made much more explicit in Mahāyāna Buddhism than in Platonism, but I believe there is some common ground.

— Wayfarer — javra

Further to this, and apropos of the issue of esoteric philosophy. The following is a comparison of a passage from Parmenides, who is generally understood as the originator of classical metaphysics, and an esoteric school of Mahāyāna Buddhism called Mahamudra.

Parmenides is generally understood as a mystical philosopher, his prose-poem was delivered to him verbatim by 'the Goddess' that he met 'on the plains beyond the gates of day and night'.

From the final section of Parmenides:

That being is free from birth and death

Because it is complete, immutable and eternal.

It never was, it never will be, because it is completely whole in the now,

One, endless. What beginning, indeed, should we attribute to it?

Whence would it evolve? Whither?

I will not allow you to say or to think that it comes from nothingness,

Nor that being is not. What exigency would have brought it forth

Later or earlier, from nonbeing?

....

Being the ultimate, it is everywhere complete.

Just as an harmoniously round sphere

Departs equally at all points from its center.

Nothing can be added to it here nor taken away from it there.

What is not, cannot interrupt it’s homogeneous existence.

What is, cannot possess it more or less. Out of all reach,

Everywhere identical to itself, beyond all limits, it is.

Compare a passage from the Aspiration Prayer of Mahamudra:

It is not existent--even the Victorious Ones do not see it.

It is not nonexistent--it is the basis of all Saṃsāra and Nirvāṇa.

This is not a contradiction, but the middle path of unity.

May the ultimate nature of phenomena, limitless mind beyond extremes, be realised.

If one says, "This is it," there is nothing to show.

If one says, "This is not it," there is nothing to deny.

The true nature of phenomena,

which transcends conceptual understanding, is unconditioned.

May conviction be gained in the ultimate, perfect truth. -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?Now you might believe that some have attained knowledge of them, but that is just an opinion — Fooloso4

You keep saying that 'we' do not know and can never know the forms - does this 'we' include Plotinus, Proclus, all the philosophers before and since? Perhaps the reason 'we' do not have knowledge of them is because of the very materialism you deem not worth discussing. Might that not be a blind spot? -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?Yes, it probably says so much about Western culture and the nature of consumerism and shallowness — Jack Cummins

'Consumer culture' is the engine of capitalism, the whole world's economy depends on it. And it's really diametrically opposed to any form of renunciate philosophy, as many have pointed out. -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?What is made explicit, as I have pointed out, is that all of the Forms are beyond coming-to-be and passing away but unlike the Good, they are said to be entirely and to be entirely knowable. — Fooloso4

In the Analogy of the Divided Line, isn't knowledge of the forms distinguished from knowledge of sensible things, and knowledge of geometery and mathematics? Knowledge of the forms being described as 'noesis', that which is the activity or pertains to nous, intellect.

I think that for heuristic purposes, a distinction can be made between 'being' and 'existence'. This is not a distinction that is intelligible in Ancient Greek due to the specific characteristics of the Greek verb 'to be' (for which see an illuminating paper The Greek Verb 'To Be' and the Problem of Being, Charles Kahn.) The distinction between reality and existence draws attention to the fact that the forms (i.e. intelligible objects) are not existent qua phenomena ('phenomena' being appearance). They are properly speaking noumenal objects, not in the Kantian sense of an unknown thing, but an 'object of nous'. So, in that sense, they are real but not existent (hence my rhetorical question, 'does the number 7 exist?')

Lloyd Gerson puts it like this in his paper Platonism Vs Naturalism:

Aristotle, in De Anima, argued that thinking in general (which includes knowledge as one kind of thinking) cannot be a property of a body; it cannot, as he put it, 'be blended with a body'. This is because in thinking, the intelligible object or form is present in the intellect, and thinking itself is the identification of the intellect with this intelligible. Among other things, this means that you could not think if materialism is true… . Thinking is not something that is, in principle, like sensing or perceiving; this is because thinking is a universalising activity. This is what this means: when you think, you see - mentally see - a form which could not, in principle, be identical with a particular - including a particular neurological element, a circuit, or a state of a circuit, or a synapse, and so on. This is so because the object of thinking is universal, or the mind is operating universally.

This implication of matter-form dualism is preserved in Thomist philosophy:

if the proper knowledge of the senses is of accidents, through forms that are individualized, the proper knowledge of intellect is of essences, through forms that are universalized. Intellectual knowledge is analogous to sense knowledge inasmuch as it demands the reception of the form of the thing which is known. But it differs from sense knowledge so far forth as it consists in the apprehension of things, not in their individuality, but in their universality. — Thomistic Psychology: A Philosophical Analysis of the Nature of Man, by Robert E. Brennan

So, put roughly, the ideas are real, but not phenomenally existent. The sensible phenomenon is existent, but not truly real. Of course modern philosophy is overall nominalist and empiricist and will not acknowledge these ideas. That is why Gerson argues that Platonism and naturalism are incommensurable.

Again, to try and contextualise this, against the background of the scala naturae, the great chain of being, it means that sensible objects, being material, are at the lowest level. Matter is 'informed' by the ideas as wax is by the seal. That is the sense in which they're higher and less subject to decay (i.e. passing in and out of existence). -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?Some people do seem to seek for 'enlightenment' or even the bliss of 'Nirvana' as an end. — Jack Cummins

Considerably more than a few. It’s a multi-million dollar business. A while back there was a series of lawsuits in the USA over the copyright on any number of Sanskrit terms associated with yoga studios and yoga practice. If it’s not worth money, it doesn’t mean anything to a lot of people. -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?comparison:

There is no scientific evidence for physicalism.

— Wayfarer

'There is no scientific evidence for evolution.'

'There is no scientific evidence for the earth being billions of years old.'

See the science denialist pattern?

You flatter yourself by referring to yourself as "questioning". — wonderer1

I fully accept the established facts of evolution and cosmology. But they do not necessarily entail physicalism. They are equally compatible with an idealist philosophy. The fact that you think they’re in conflict is only due to your stereotyped ideas of what you think idealism must entail. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Indeed. I'm very unimpressed by Fani T. Willis. Can't afford these kinds of slip-ups considering the gravity of the case. But at the same time, as the article notes, there are a number of other cases involving Trump. The January 6th trial will be the truly momentous one - no slip ups from Jack Smith (although the trial date has slipped.) But if Trump is convicted of those charges, and even if it's technically possible to be elected President after conviction, in practical terms I can't see how his candidacy would survive. I also wonder if the Supreme Court's decision on his eligibility will take the outcome of that trial into account, because it damn well should.

-

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?Don't you think however that there is also a lot of hostility in the other direction (from those who hold idealist positions), who persistently disparage physicalists? — Tom Storm

I myself try to refrain from sarcastic or ad hominem criticisms. Although I did notice recently that I was compared to a young-earth creationist for questioning what I call 'common-sense physicalism' (i.e. the idea that the mind can be understood through neuroscience). Of course I criticize physicalism, as I think of it as something like a popular myth. It's something that is generally just assumed to be the case, as being self-evident, 'common sense', such that questioning it seems incredible to a lot of people. (I was rather put off by the strident hostility and polemicism of Kastrup's book Materialism Is Baloney, even though on the whole I'm in Kastrup's corner. I think it can be criticized without that kind of language. )

Regarding Bhikkhu Bodhi's talk - the context of that was a keynote speech at an interfaith conference. (Bhikkhu Bodhi, born Jeffrey Block, is an American monk who was English-language editor of the Buddhist Texts Publication Society.) I don't think that description he gives is at all exagerrated or overly polemical.

For Strauss, there were three levels of the text: the surface; the intermediate depth, which I think he did think is worked out; and the third and deepest level, which is a whole series of open or finally unresolvable problems ~ Stanley Rosen. — Fooloso4

In the SEP entry on Strauss I note that the relationship of 'reason and revelation' is one of the over-arching themes of his work:

[Strauss] criticizes the modern critique of religion beginning in the 17th century for advancing the idea that revelation and philosophy should answer to the same scientific criteria, maintaining that this notion brings meaningful talk of revelation to an end, either in the form of banishing revelation from conversation or in the form of so-called modern defenses of religion which only internalize this banishment. Strauss’s early musings on the theologico-political predicament led him to a theme upon which he would insist again and again: the irreconcilability of revelation and philosophy (or the irreconcilability of what he would call elsewhere Jerusalem and Athens or the Bible and Greek philosophy). Strauss maintains that because belief in revelation by definition does not claim to be self-evident knowledge, philosophy can neither refute nor confirm revelation:

The genuine refutation of orthodoxy would require the proof that the world and human life are perfectly intelligible without the assumption of a mysterious God; it would require at least the success of the philosophical system: man has to show himself theoretically and practically as the master of the world and the master of his life; the merely given must be replaced by the world created by man theoretically and practically (SCR, p. 29).

Because a completed system is not possible, or at least not yet possible, modern philosophy, despite its self-understanding to the contrary, has not refuted the possibility of revelation. On Strauss’s reading, the Enlightenment’s so-called critique of religion ultimately also brought with it, unbeknownst to its proponents, modern rationalism’s self-destruction. Strauss does not reject modern science, but he does object to the philosophical conclusion that “scientific knowledge is the highest form of knowledge” because this “implies a depreciation of pre-scientific knowledge.” As he put it, “Science is the successful part of modern philosophy or science, and philosophy is the unsuccessful part—the rump” (JPCM, p. 99). Strauss reads the history of modern philosophy as beginning with the elevation of all knowledge to science, or theory, and as concluding with the devaluation of all knowledge to history, or practice

In other words, Strauss admits the possibility of religious revelation throughout his work. What he does not seem to consider, it seems to me, is the possibility of gnosis or divine illumination, which seems distinguishable from 'revelation'. Nevertheless, obviously a scholar of great depth and range, someone else I'll never really get the chance to read. -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?You clearly take issue with Fooloso4 for a secular and, shall we say, 'modern' reading of Plato and Aristotle? You think his take, though scholarly, stops short where it matters, right? — Tom Storm

I respect his knowledge of the texts and have benefitted from it in many discussions about Plato. And I’m also aware of the deficiencies of own learning. In generations past, these texts were the subject of The Classics and classical education but I encountered little of them until well into adulthood. But on the other hand, Plato is one of the founding figures of Western culture and I feel as though a certain amount of it has seeped in to me solely due to my cultural heritage (and I have at least done some readings) But as I now understand it, a classical education in Plato required reading all the dialogues, in a prescribed order, and with associated commentary, as part of a structured curriculum. At this stage in life, I am not going to achieve that.

So I’m not equipped to criticise Fooloso4’s interpretation, save to say that in my view it’s rather deflationary. I think Plato’s dialogues can be read on many levels and are open to many kinds of interpretation, and that there are kind of ‘off-ramps’ for those who are not inclined to the esoteric face of his philosophy. But I agree with Lloyd Gerson that Platonism and naturalism are incommensurable, whereas for most here, naturalism is axiomatic and anything that can be categorised as supernatural - and it’s a broad brush! - is off limits.

At heart in most of these discussions you hold the position that there is a realm beyond the quotidian world and that this can be understood/accessed through a range of approaches - e.g., Buddhism, Tao, Jnana Yoga, and the classical Western philosophical tradition, which has been filleted by secularism and modernist understandings. — Tom Storm

That’s what philosophy is, or used to be. Pierre Hadot makes that quite clear in his ‘Philosophy as a Way of Life’ and other publications. I think the watershed was the division of mind and matter, and primary and secondary attributes, associated with Galileo, Descartes and Newton and ‘the scientific revolution’.

The underlying historical cause of this phenomenon seems to lie in an unbalanced development of the human mind in the West, beginning around the time of the European Renaissance. This development gave increasing importance to the rational, manipulative and dominative capacities of the mind at the expense of its intuitive, comprehensive, sympathetic and integrative capacities. The rise to dominance of the rational, manipulative facets of human consciousness led to a fixation upon those aspects of the world that are amenable to control by this type of consciousness — the world that could be conquered, comprehended and exploited in terms of fixed quantitative units. This fixation did not stop merely with the pragmatic efficiency of such a point of view, but became converted into a theoretical standpoint, a standpoint claiming validity. In effect, this means that the material world, as defined by modern science, became the founding stratum of reality, while mechanistic physics, its methodological counterpart, became a paradigm for understanding all other types of natural phenomena, biological, psychological and social.

The early founders of the Scientific Revolution in the seventeenth century — such as Galileo, Boyle, Descartes and Newton — were deeply religious men, for whom the belief in the wise and benign Creator was the premise behind their investigations into lawfulness of nature. However, while they remained loyal to the theistic premises of Christian faith, the drift of their thought severely attenuated the organic connection between the divine and the natural order, a connection so central to the premodern world view. They retained God only as the remote Creator and law-giver of Nature and sanctioned moral values as the expression of the Divine Will, the laws decreed for man by his Maker. In their thought a sharp dualism emerged between the transcendent sphere and the empirical world. The realm of "hard facts" ultimately consisted of units of senseless matter governed by mechanical laws, while ethics, values and ideals were removed from the realm of facts and assigned to the sphere of an interior subjectivity.

It was only a matter of time until, in the trail of the so-called Enlightenment, a wave of thinkers appeared who overturned the dualistic thesis central to this world view in favor of the straightforward materialism. This development was not a following through of the reductionistic methodology to its final logical consequences. Once sense perception was hailed as the key to knowledge and quantification came to be regarded as the criterion of actuality, the logical next step was to suspend entirely the belief in a supernatural order and all it implied. Hence finally an uncompromising version of mechanistic materialism prevailed, whose axioms became the pillars of the new world view. Matter is now the only ultimate reality, and divine principle of any sort dismissed as sheer imagination.

The triumph of materialism in the sphere of cosmology and metaphysics had the profoundest impact on human self-understanding. The message it conveyed was that the inward dimensions of our existence, with its vast profusion of spiritual and ethical concerns, is mere adventitious superstructure. The inward is reducible to the external, the invisible to the visible, the personal to the impersonal. Mind becomes a higher order function of the brain, the individual a node in a social order governed by statistical laws. All humankind's ideals and values are relegated to the status of illusions: they are projections of biological drives, sublimated wish-fulfillment. Even ethics, the philosophy of moral conduct, comes to be explained away as a flowery way of expressing personal preferences. Its claim to any objective foundation is untenable, and all ethical judgments become equally valid. The ascendancy of relativism is complete. — “Bhikkhu Bodhi, A Buddhist Response to the Contemporary Dilemmas of Human Existence

Not everyone will defend so stark a position as expressed here, but it is undeniably a major influence on today’s culture. And do notice the hostility that criticism of it engenders. I’m never one to deny that I am ignorant in many things, but I don’t proclaim that ignorance as a yardstick of what ought to be discussed. -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?Does the number 7 come into being and pass away? — Fooloso4

I would say plainly not. You will recall that Jacob Klein book that you recommended me, which I have read, in part, although much of it is very specialised. But it does affirm a very general point about Platonist philosophy of mathematics, to wit:

Jacob Klein, Greek Mathematical Thought and the Origin of Algebra.Neoplatonic mathematics is governed by a fundamental distinction which is indeed inherent in Greek science in general, but is here most strongly formulated. According to this distinction, one branch of mathematics participates in the contemplation of that which is in no way subject to change, or to becoming and passing away. This branch contemplates that which is always such as it is and which alone is capable of being known: for that which is known in the act of knowing, being a communicable and teachable possession, must be something that is once and for all fixed

This is why knowledge of geometry and arithmetic, dianoia, was held to be 'higher' than knowledge of sensible things. It is paradigmatic for 'the unity of thinking and being', which, according to Perl, is the underlying theme of the Western metaphysical tradition.

We remain in the cave of opinion — Fooloso4

Very much your opinion, in my opinion. -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?But the Forms that are affirmed to exist, to be, are said to be 'beyond coming-to-be and passing away'. — Fooloso4

Right - but if they are 'beyond coming-to-be and passing away', then how can they be said to exist? Of all the things around us, which of them does not come into existence or pass away. Doesn't that apply to all phenomena?

An illustration: does the number 7 exist? Why, of course, you will say, there it is. But that's a symbol. The symbol exists, but what is symbolised? Are numbers 'things that exist'? Well, in a sense, but the nature of their existence is contested by philosophers - very much to the point. And it's also a point made in the passage from Eriugena, where things that exist on one level, do not exist on another. That's what makes all of this a metaphysical question.

My heuristic is that forms (etc) don't exist, but they are real, in an analogous sense to the way constraints are real in systems science. They are something like the way things must be, in order to exist - like blueprints or archetypes. Like, the form 'flight' can only be instantiated by wings that are flat and light. The form 'seeing' can only be instantiated by organs that are light-sensitive. And so on. But they don't exist as do the particulars which instantiate them. -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?Socrates, who tells this story of transcendent knowledge, does not know. His human wisdom is his knowledge of ignorance. — Fooloso4

I think that's a very delicate question of interpretation. Later in the tradition of Christian Platonism, there is the principle of 'un-knowing', apophatic theology and the 'way of negation'. It is a universal theme also found in Indian and Chinese philosophy ('he that knows it, knows it not. He that knows it not, knows it'; 'Neti, neti' ~ 'not this, not that'.) So perhaps 'ignorance' in this context means something different than what it is normally taken to mean.

(I also notice a remark in 'Thinking Being', that Parmenides' prose-poem has been given to him by 'The Goddess', and so 'this grasp of the whole (which is the subject of the proem) is received as a gift from the Divine'. Perl also mentions Heraclitus' dictum 'Human character does not have insights, divine has' - Thinking Being, Studies in Platonism, Neoplatonism and the Platonic Tradition, Eric D. Perl, Brill, 2014).

Perhaps this separation of the world from the Divine that we moderns axiomatically assume (if we even make room for the divine!) was not so stark for the Greek philosophers.

The danger of 'woo' may be more connected with concrete thinking, especially in organised religious movements. — Jack Cummins

It's more that as enlightenment is taken to be the universal panacea, the supreme good, then everyone wants it, or wants what they think it is. It is therefore ripe for exploitation by the cynical of the gullible, who exist in very large numbers. And it's also very difficult to differentiate actual mysticism from mystical-sounding waffle, so there's abundant scope for delusion in this domain.

But as Rumi said, there would be no fool's gold, if there were no actual gold.

“... although the good isn't being but is still beyond being, exceeding it in dignity (age) and power."(509b) — Fooloso4

As to the Good being beyond being, while I don't speak Greek, much less Ancient Greek, there seems to be something lost in translation. — javra

My interpretation of 'beyond being' is that it means 'beyond the vicissitudes of existence', 'beyond coming-to-be and passing away'. That idea is made much more explicit in Mahāyāna Buddhism than in Platonism, but I believe there is some common ground. And that the reason intelligible objects such as geometric forms and arithmetic proofs are held in high regard (in Platonism, not so much in Buddhism) is that they are not subject to becoming and ceasing, in the way that sensible objects and particulars are. So they are 'nearer' to the ground of being, or 'higher' in the scala naturae, the great chain of being.

There's an account of this in John Scotus Eriugena, The Periphyseon, from the SEP entry on which this excerpt is taken. I have taken the liberty of striking out 'to be' and replacing it with 'to exist', as I think it conveys the gist better.

Eriugena proceeds to list “five ways of interpreting” the manner in which things may be said tobe or not to beexist or not to exist (Periphyseon, I.443c–446a). According to the first mode, things accessible to the senses and the intellect are said tobeexist, whereas anything which, “through the excellence of its nature” (per excellentiam suae naturae), transcends our faculties are said not tobeexist. According to this classification, God, because of his transcendence is said not tobeexist. He is “nothingness through excellence” (nihil per excellentiam). 1

The second mode of being and non-being is seen in the “orders and differences of created natures” (I.444a), whereby, if one level of nature is said tobeexist, those orders above or below it, are said not tobeexist:

For an affirmation concerning the lower (order) is a negation concerning the higher, and so too a negation concerning the lower (order) is an affirmation concerning the higher. (Periphyseon, I.444a)

According to this mode (of analysis), the affirmation of man is the negation of angel and vice versa. This mode illustrates Eriugena’s original way of dissolving the traditional Neoplatonic hierarchy of being into a dialectic of affirmation and negation: to assert one level is to deny the others. In other words, a particular level may be affirmed to be real by those on a lower or on the same level, but the one above it is thought not to be real in the same way. If humans are thought to exist in a certain way, then angels do not exist in that way.

1. The sense in which is God is 'above' or 'beyond' existence, and, so, not something that exists, is central the apophatic theology. It was a major theme in the theology of Tillich, who said that declaring that God existed was the main cause of atheism. See God Does Not Exist, Bishop Pierre Whalon.

That SEP entry on Eriugena was written by Dermot Moran, who is also a scholar of phenomenology and Edmund Husserl. He has a book which argues that Eriugena's was a form of medieval idealism that was to greatly influence the later German idealists (via Eckhardt and the medieval mystics).

My interpretation of the forms/ideas is that they too are beyond the vicissitudes of existence and non-existence, that they don't come into or pass out of existence. And so, literally speaking, they don't need to exist! Things do the hard work of existence. Or, put another way, they exist 'in a different way' or 'on a different level' to material things. But modern ontology does not generally allow for 'different ways of existing' or 'different levels of existence'. It is strictly one-dimensional. That's the nub of the issue. -

Lost in transition – from our minds to an external world…the world before humanity even existed. — Janus

'Before' is a concept. -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?'Esoteric' is not a school of thought or a philosophy in its own right. Many different philosophical traditions have esoteric schools, be they Buddhist, Platonist, Christian, or Vedanta. The dictionary definiton of 'esoteric' is 'intended for or likely to be understood by only a small number of people with a specialized knowledge or interest.' It applies to other disciplines as well, like mathematical physics and other specialised subjects, although what is spiritually esoteric includes an existential dimension that may be absent from them (although as is well-known Einstein and many of the first-gen quantum physicists had their mystical side.) It might be a ‘religious’ dimension, but at issue in that categorisation, and of special relevance in this topic, is what religious means. Spinoza, for instance, being discussed in another thread, is claimed as one of the founders as secular culture, but he’s also been described as ‘God intoxicated’ (as was Krishnamurti after the legendary encounter under the tree in his first visit to Ojai.)

I'm reading a very hard-to-find textbook, Thinking Being, by Eric D Perl, 'metaphysics in the classical tradition'. The whole point of the book is 'the identity of thought and being'. He starts with Parmenides, then Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus and Aquinas, and claims to be explicating a common theme found in all of them. But it occurs to me that it's not at all clear what 'thought' means in this context. I'm sure it doesn't mean the ordinary 'stream of consciousness' that occupies our mental life from moment to moment - what we generally understand by ‘thought’ It’s much nearer in meaning to the Sanskrit 'citta' which is translated 'mind', 'heart', or 'being', depending on the context. Perhaps it’s nearer in meaning to the idea that ‘the thought of the world is the world’.

Speaking of Krishnamurti (and of esoteric teachings), here is a characteristic remark:

What is the basic reason for thought to be fragmented?

What is the substance of thought? Is it a material process, a chemical process?

There is a total perception, which is truth. That perception acts in the field of reality. That action is not the product of thought.

Thought has no place when there is total perception.

Thought never acknowledges to itself that it is mechanical.

Total perception can only exist when the centre is not. — J Krishnamurti

Now, I would contend that what is referred to as ‘’thought’ in Perl’s ‘Thinking Being’, and what Parmenides means by ‘thought’, is exactly what K. means by ‘total perception’. It is an insight into the whole of existence. Not a scientific insight, obviously, as scientific knowledge of reality far, far exceeds what any one individual may know or comprehend. Rather it is the ‘unitive vision’ of both mysticism and philosophy. Krishnamurti often refers to an insight which acts ‘at a glance’, as it were (I think a term for this is ‘aperçu’.) It is distinct from deliberation or a gradual process of disclosure, but a sudden insight which reveals a hitherto unseen vista, like a lightning bolt (that being one of the seminal images of Tantra.) ‘When the centre is not’ means what is seen when all sense of ‘I am seeing this’ is in abeyance.

And I think that insight shows that what we take to be thought, and what we take to be reality, are themselves states of misunderstanding (avidyā) - which modern culture takes as normality. So, it is to be expected that very few see it.

Which is what makes it ‘esoteric’. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)Shouldn’t be surprise anyone, they’re a party of secessionists. 149 of them voted not to recognise the result of the last Presidential election. They’re spoiling for a fight but I hope it’s one they eventually lose.

-

How Different Are Theism and Atheism as a Starting Point for Philosophy and Ethics?Do you not put forward Descartes as the poster child for "instrumental reason"? — Paine

Well, insofar as he was 'the first modern philosopher', which was how he was presented to me in undergrad philosophy. And the modern period is where the instrumental conception of reason really becomes entrenched. Prior to that it was accepted that reason was embedded in the fabric of the cosmos, whereas for modern philosophy it becomes subjectivised and relativised.

Sure there are countless difference of nuance and emphasis amongst those philosophers but what I believe they all share is the sense of the qualitative dimension, that there is a real good which is not a matter of definition or social convention.

In contrast to contemporary philosophers, most 17th century philosophers held that reality comes in degrees—that some things that exist are more or less real than other things that exist. At least part of what dictates a being’s reality, according to these philosophers, is the extent to which its existence is dependent on other things: the less dependent a thing is on other things for its existence, the more real it is. — IEP -

How Different Are Theism and Atheism as a Starting Point for Philosophy and Ethics?:The theological assumption is comparable to Aristotle appealing to the agent intellect and the unmoved mover. — Paine

Indeed!

Another way to put this is that the more capable we are of reasoning correctly, the more perfect and happy we are (Part V, "The Power of the Human Intellect or Human Freedom, Proposition 31). In other words the more perfect our knowledge the more godlike we become. — Fooloso4

This is comparable to a passage from the Nichomachean Ethics:

if happiness [εὐδαιμονία] consists in activity in accordance with virtue, it is reasonable that it should be activity in accordance with the highest virtue; and this will be the virtue of the best part of us. Whether then this be the Intellect [νοῦς], or whatever else it be that is thought to rule and lead us by nature, and to have cognizance of what is noble and divine, either as being itself also actually divine, or as being relatively the divinest part of us, it is the activity of this part of us in accordance with the virtue proper to it that will constitute perfect happiness; and it has been stated already* that this activity is the activity of contemplation — Nichomachean Ethics

This quoted passage is also directly comparable:

Therefore this love (by 3p59 and 3p3) must be related to the mind insofar as it acts; and accordingly (by 4def8) it is virtue itself. That is the first point. Then, the more the mind enjoys this divine love or blessedness, the more it understands (by 5p32), i.e. (by 5p3c) the greater the power it has over its emotions and (by 5p38) the less it is acted on by emotions that are bad. Therefore because the mind enjoys this divine love or blessedness, it has the ability to restrain lusts — ibid. part 5 proposition 42

likewise could be taken virtually unchanged from many a volume of the philosophia perennis, and even from some religious tracts (even some East Asian Buddhist religious tracts on Buddha Nature).

But in all these, 'reason' is being understood in a sense much nearer to 'logos' than today's 'instrumental reason', is it not? Spinoza seems much nearer to Aristotle than to current conceptions of reason in this regard, does he not? -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?One factor to consider is the role of initiation and guidance in esoteric teachings.

Instances are found in different traditions, but one example is the understanding that Plato's written teachings, or what was preserved in the transcribed dialogues, was supplementary to an unwritten doctrine (which obviously we know nothing about!)

A book that @Fooloso4 alerted me to, Philosophy Between the Lines - the Lost History of Esoteric Writing, James Melzer, discusses the esoteric in relation to philosophy proper. He says esoteric writing in philosophy 'relies not on secret codes, but simply on a more intensive use of familiar rhetorical techniques like metaphor, irony, and insinuation.' And also the capacity of the aspirant to read between the lines - to catch an allegorical element that may or may not be there. And that is dependent on the student's acuity, their own ability to absorb what is being said.

Another that I discovered in Buddhist Studies was The Twilight Language by Roderick Bucknell, which explores the symbolism of Buddhist teachings from the Pali through to Tantra. All throughout Buddhist culture, there is an interplay of teaching, symbolic form, allegory and metaphor, embodied even in the sacred architecture of the Stupas or the symbolic contents of sacred art and iconography.

So, why the need for these allusive and metaphorical modes of expression? Isn't it because the real meaning can't simply be spelled out, made explicit? That what is being conveyed, teacher to student, is something that requires a certain kind of insight, and one that not everybody possesses? 'Those who have ears to hear, let them hear'. Or eyes to see, for that matter. Secular culture is deeply inimical to that kind of ethos, we expect, indeed demand, that whatever is worth knowing is 'in the public domain', that it can be explained 'third person', so to speak. Hence the tension between traditionalism and modernity, often resulting in the association of traditionalism with reactionary politics.

The point being the subjects at issue are deep and difficult to convey, although again, in the modern world, with universal access to all kinds of information, that can also be lost sight of. When the Chinese monks Faxian and Xuangzan travelled east from the Heavenly Kingdom in the 3rd-4th centuries CE, they had to travel with oxen and donkeys, on foot, across deserts and mountains, beset by bandits and other dangers, to bring back the precious Buddhist scrolls from India. Now, translations of all these texts are freely available to anyone with a computer in the comfort of their study. So what? we will say. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)Senators grilled the CEOs of Meta, TikTok, Snap, Discord and X Wednesday in a heated hearing about harm posed to teens and kids online. — The Hill

How about grilling the CEOs of the very many major gun manufacturing companies about the horrors wrought by their wares? You know, Remington, Smith and Wesson, and the others? In addition to gun suicides there are also the many thousands of 'young people' shot and wounded or killed, many while attending school. But no, strangely enough- guns don't kill people, but social media kills people. And a much less controversial target, to boot. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)What does the fact that Trump and people like him can do well in this world say about the world? — baker

Nothing about 'the world' in particular, but a shameful reflection of the American electorate. The fear is simply for the destruction of civil society that would ensue from his re-election, although I'm sure that it won't happen. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)I think from what I'm reading in this thread, there's a lot of psychological fear of the idea that Trump might be president again. — L'éléphant

Not 'psychological'. Fear, period. Although as I’ve said, I don’t believe it.

It occurs to me, speaking of psychology, that Trump’s thinking is entirely and completely subjective. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)Of course it is. It's what happens when halfwits like Marjorie Taylor Greene are in charge of the henhouse. It's never about governance, only petty point-scoring.

-

How Different Are Theism and Atheism as a Starting Point for Philosophy and Ethics?God was happy t — Corvus

The KJV says 'And God saw the light, that it was good.’ The attribution of emotion is yours. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)So, the Republicans are impeaching the Homeland Security secretary, on Trumped-up grounds, while at the same time their leader, Donald Trump, pushes them to torpedo the solution to the border security problem that this Secretary is being accused of neglecting, while in reality he has been involved with a bi-partisan solution.

Democrats... criticized the impeachment proceedings as politically motivated, pointing out that GOP lawmakers were trying to oust Mayorkas for supposedly neglecting to secure the southern border, while at the same time opposing a bipartisan package under negotiation in the Senate that would seek to improve border security. — Washington Post

It's astounding, the levels of hypocrisy, doubletalk and duplicitiousness the MAGA will sink to. -

Epistemology – Anthropic RelativismInstrumentalism, constructivism, genetic epistemology and rejection of everything esoteric and religious. — Wolfgang

I can deduce that from this and also your previous posts. I ascribe that to the fear of religion.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum