Search

-

Speculation: Eternalism and the Problem of Evil

:clap: The 'promethean' nature of science - 'stealing fire from the Gods' - is sometimes cited.

At death breath leaves the body. It is from this natural observation that these terms go on to develop mythologies, metaphysical meaning, — Fooloso4

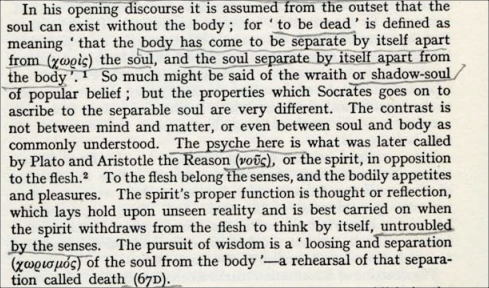

One of the earlier discussion you referenced contains a link to the Cornford book Plato's Theory of Knowledge from the introduction of which I copy (the 'opening discourse' is from the Phaedo):

I don't find that account implausible, from a philosophical perspective. It also foreshadows the later 'doctrine of the rational soul' you find in Thomas. In that later form of hylomorphism, nous is what grasps the form or principles of things, while the senses perceive its material (accidental) features.

@Leontiskos

(As a footnote, I sometimes wonder if what is meant by 'thinking' or 'reason' in the Platonic dialogues is something completely different from what we mean by thought. I think it's referring to something much more like 'insight' or 'intuitive grasp' than the passing montage of words, images and ideas that we usually designate 'thought'. "It is by seeing what justice is that one becomes just; by seeing what wisdom is, that one becomes wise.") -

Best Arguments for Physicalism

The Platonic concept of Body/Soul integrity, as a harmonious interaction, is new to me. So I googled it. As an analogy to pleasing musical synchrony*1, such essential consonance is posited by most religious & philosophical traditions : e.g Taoism. But from the perspective of modern Physicalism, such non-mechanical notions may be dismissed as romantic nonsense.I was just reading the Phaedo for a class and it hit me that Plato's argument that the soul cannot be analogous to a harmony is literally the same argument against strong emergence that is still giving physicalists a headache 2,000+ years later. — Count Timothy von Icarus

However, while my own personal worldview does not use the obsolete term "Soul" --- in the sense of an independent ghost --- the unity of Body & Mind is implicit. So, I see now that "Person"*2 can be described in terms of Body/Mind harmony, as defined in the 20th century sciences of Holism*3 and Systems theory*4. A System is a collection of independent parts (holons) that work together, in harmony, to form a new unity, with new functions. Hence, the human body/mind is an animated & enminded system that can't be separated into parts without killing the Life and extinguishing the Mind. Since Life & Mind go together like a flock of birds, eliminating one or the other will not result in a philosophical zombie, but in a corpse. :smile:

*1. What is Synchrony in music?

Musical synchrony increases a sense of shared intentionality and decreases the experience of self-other distinction [21,22,23,24], and can relate to a sense of communal identity

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8946180/

*2. Person :

A person is a being who has certain capacities or attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or self-consciousness,

Note --- That the "Being" --- more than a Thing --- is also a physical body is implicit, but not stated explicitly in the definition.

*3. Holism ; Holon :

Philosophically, a whole system is a collection of parts (holons) that possesses properties not found in the parts. That something extra is an Emergent quality that was latent (unmanifest) in the parts. For example, when atoms of hydrogen & oxygen gases combine in a specific ratio, the molecule has properties of water, such as wetness, that are not found in the gases. A Holon is something that is simultaneously a whole and a part — A system of entangled things that has a function in a hierarchy of systems.

https://blog-glossary.enformationism.info/page11.html

*4. What is holistic science? :

Holistic Science is a new and emerging science of systems and wholes, qualities and values. It allows us to look at the social, economic and ecological issues of the 21st Century in a new light. It helps us to come to understandings that go beyond the limits of our current scientific paradigm.

https://www.masterscompare.co.uk/masters-courses/holistic-science-23096/24594/

A HARMONY OF BIRDS

-

Best Arguments for Physicalism

Phaedo is one of my favorite philosophical works. I also disagree with your interpretation, and indeed your whole take on Plato. But there's always room for diverse views. It creates dynamism in discussions. -

Best Arguments for Physicalism

But there's always room for diverse views. It creates dynamism in discussions. — frank

Yes, it does. But out of respect for your present thread on physicalism I am trying to not veer too far off topic with a discussion of Phaedo and the problem of interpreting Plato in this thread. -

Best Arguments for Physicalism

Yes, it does. But out of respect for your present thread on physicalism I am trying to not veer too far off topic with a discussion of Phaedo and the problem of interpreting Plato in this thread. — Fooloso4

Thank you. -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?

I find it hard to know how Socrates and Plato thought of immortality. — Jack Cummins

The fact of the matter is: they don't know, but there are serious problems that cast doubt on the possibility. As with Forms and particulars one is the difference between the Form Soul and the soul of an individual. Another is the difference between a person and his soul. Even if the soul is immortal that does not mean that the person is. In one formulation Socrates' death means the separation of body and soul. His soul can become the soul of something else (Phaedo 82a-b), but what would it mean for Socrates to become an ass?

The idea of a 'heaven within' seems important in the interpretation of the Christian teaching, — Jack Cummins

There is no such thing as "the 'Christian teaching". There are various teaching within the NT, inspired teachings many of which were destroyed by the Church Fathers as heretical, and teaching that developed later such as the "official doctrines" determined by the Council of Nicaea. In addition there are the practices of esoteric interpretation and mystical Christian teachings.

The idea of inner wealth of 'heaven within' is also captured in the Buddhist emphasis on nonattatchment. — Jack Cummins

I tend to stay away from such comparisons where similarities are pointed out and differences ignored. In addition there is the problem of translation. Terms such as 'heaven' are typically unduly inflluenced by Western Christian perspectives. I do not know enough to sort it all out and suspect that most others cannot either. -

How May Esoteric Thinking and Traditions be Understood and Evaluated Philosophically?

I have read 'Phaedo' a few years ago and did read some of the thread on it on this forum, which I found helpful in thinking about the book.

The entire idea of 'soul' is a very complex idea and used in such varying ways, including the question of the individual soul and beyond. I managed to think about it more clearly in relation to the transpersonal school of thought, including the ideas of Thomas More, which is more about the depths of human nature than a literal entity which survives as an individual construct.

You are quite right to say that there are no clear Christian teachings because there are so many cross currents of thought, ranging from influences as diverse as Egyptian idea and the blending of ideas from Plato and Aristotle, such as in the thinking of Augustine and Aquinas, as well as ideas of Plotinus and many influences.

It is probably wise to stay away from comparisons of Christianity and Buddhism which gloss over differences. I may have been influenced by such texts because I have read theosophical authors. Also, I probably dipped in and out of various Eastern texts in a rather chaotic manner, including those such as 'The Tibetan Book of the Dead'. In some ways, the academic study of the comparative religion is probably the most thorough. I did do a year of undergraduate studies in religious studies but that only covered the mere basics. Certainly, when studying Hinduism I was aware of the problems of translation and was at least fortunate to have a tutor who had studied Sanskrit.

There is a danger of oversimplification and generalisations in approaching the various traditions. I am sure that this can result in some very confused thinking. I am sure that I have blended ideas together in a very haphazard way at times and it is easy to end up with some very strange conclusions, which may show the dangers of the speculative imagination in philosophy. -

Is Knowledge Merely Belief?

It seems to me that I know my parents. I do not know them perfectly, as God knows them. I do not need to know them perfectly to know them at all. It would be more speculative — more dishonest — for me to claim that I know nothing of my parents than to admit I know something about them.

As St. Thomas says in his commentary on Boethius, all knowledge is received in the manner of the receiver. The human intellect's grasp on the intelligibility of things is necessary finite, imperfect, discursive and processual. We do not grasp things in their entirety, nor is what we grasp present to us all at once. This is simply the nature of human knowledge, that it is not angelic knowledge. But this does not make it such that there is no such thing as human knowledge, only knowledge from the "God's eye view."

. I admit to knowing nothing, but I claim to be aware of many things. Those are not the same things to me. Indeed, people react less well in general to someone claiming some awareness than they do to someone lying to them and claiming knowing. This is a terrible problem with understanding in most people. It is inherently more correct to applaud and suffer with the person only claiming some awareness. That is the gist of my claim stated fairly plainly.

I take it that you then might agree with the following claims, that human beings are intrinsically motivated to seek truth, to attain to veracity

By veracity I do not mean a virtue; it is something more elementary. It is in us from the beginning. Veracity is the impulse toward truth, and the virtue of truthfulness is its proper cultivation. Veracity is the origin of both truthfulness and the various ways of failing to be truthful. Thus, lying, refusing to look at important facts, being careless or hasty in finding things out, and other ways of avoiding truth are perversions of veracity, but they are exercises of it. Curiosity is a frivolous employment of it. Veracity means practically the same thing as rationality, but it brings out the aspect of desire that is present in rationality, and it has the advantage of implying that there is something morally good in the fulfillment of this desire. It also suggests that we are good and deserving of some recognition simply because we are rational. Veracity is the desire for truth; it specifies us as human beings. It is not a passion or an emotion, but the inclination to be truthful. The passions are not the only desires we have, and reason is not just their servant; we also want to achieve the truth.

If we cultivate our rationality we become truthful, and if we frustrate it we become untruthful or dishonest (or merely pedantic), but it is not the case that truthfulness and dishonesty are two equivalent alternatives for us

to pursue. It is not the case that we are defined by veracity (rationality) and that we can cultivate it in these two different ways. Being untruthful is not one of the ways of being a successful human being.

Robert Sokolowski - The Phenomenology of the Human Person

However, I think there is a misplaced sense of piety if we begin to claim that we do not know anything of our parents, anything of arithmetic, or anything of ourselves for fear of error. This strikes me as the "fear of error become fear of truth," that Hegel discusses in the preface of the Phenomenology of Spirit. For, "as a matter of fact, this fear presupposes something, indeed a great deal, as truth, and supports its scruples and consequences on what should itself be examined beforehand to see whether it is truth."

No one lives as if they actually "know nothing." Phyrro of Elis, the arch skeptic of ancient Greece was himself caught running away from a wild dog, apparently confident that it would indeed harm him if it bit him. As Aristotle remarks on such skeptics, they obviously believe they know some things, as they find their way to the Lyceum to bother him, following paths that take them there, whereas if they truly knew nothing they should not prefer one path over any other when they set out to travel to some place, or should not even assume that walking will get them from one place to another.

One cannot live into veracity while thinking they truly know nothing. To be sure, we can always doubt, just as Moore points out that we can always ask of something "is it truly good?" or just as we can always ask "is it truly beautiful?" or "why is it beautiful?" This is part of the reason that truth, beauty, and goodness were proposed as transcendentals by the scholastics. Reason is transcedent, ecstatic. We can always go past current beliefs and judgements (moral or aesthetic as well). This is what makes reason special, it's ability to transcend who we.currently are and make us into something new.

But it is a mistake to take this property of reason as grounds for doubting everything. This makes veracity impossible. We can not overcome a doubt of reason itself with reason, and this is the risk of misology. Yet embracing misology is to fail at living as a rational agent.

As Plato says in the Phaedo:

No sensible man would insist that these things are as I have described them, but I think it is fitting for a man to risk the belief—for the risk is a noble one—that this, or something like this, is true about our souls and their dwelling places …” (114d)

Belief in reason itself is a noble risk, and reason shows us we know some things. We know them in our manner, not in a divine manner. This does not mean we lack all knowledge.

Now if your point is merely to use the word "know," in a very uncoventional way, such that people don't "know their parents," or "know that two and two makes four," because radical skepticism can always ask of anything "but is it really true?" this does not seem to me like a worthwhile exercise. Not only that, but it seems that many of our experiences are not even open to this sort of doubt. If I am in terrible pain, I might very well ask, "ah, but am I truly in pain?" but to deny that I know the truth of this matter is simply self-deception. Being in terrible pain is an ostentatious reality. Likewise, if we cannot know our own propositional beliefs, then veracity becomes impossible, for we cannot even know what we hope to improve. -

Mindset and approach to reading The Republic?

In the Symposium Socrates says:

I who declare that I know nothing other than matters of love ...

At first it may seem that this contradicts what he says in the Apology where he claims to know nothing beautiful and good (21d). But eros is a desire for something one does not possess. Socrates knows the desire to be wise. This is a kind of self-knowledge. Eros is a kind of madness. The highest kind, according to Socrates in the Phaedrus, is love of the beautiful. About which Socrates makes a beautiful speech.

Toward the end of the dialogue Socrates says:

(278b)Well then, let that be the extent of our entertainment with speeches.

With regard to those who make such speeches he says:

(278d)I think it would be a big step, Phaedrus, to call him ‘wise’ because this is appropriate only for a god. The title ‘lover of wisdom’ or something of that sort would suit him better and would be more modest.

Divine madness does not lead to knowledge of the beautiful or good. It inspires does not not result in what the philosopher loves, wisdom.

The Phaedrus is a play of opposites, of things that pull us in opposite directions. For the philosopher the pull of divine madness is opposed by reason and moderation, which finds its own extreme in the asceticism of the Phaedo. In the Symposium, this plays out differently. Some of the participants are suffering from a hangover and so the usual drinking competition is replaced by the more sober competition of speeches about eros.

As Plato has Socrates tell us in the Phaedrus:

(277e)But the person who realises that in a written discourse on any topic there must be a great deal that is playful ... -

The Greatest Music

How does one know if one is being good if one doesn't know what is good or in what goodness consists? — Count Timothy von Icarus

We don't. Believing one does know when he does not is a problem.

(Phaedo 97b-d)If then one wished to know the cause of each thing, why it comes to be or perishes or exists, one had to find what was the best way for it to be, or to be acted upon, or to act. On these premises then it befitted a man to investigate only, about this and other things, what is best.

The question of what is best is inextricably linked to the question of the human good. About what is best we can only do our best to say what is best and why. The question of what is best turns from things in general to the human things and ultimately to the self for whom what is best is what matters most. The question of the good leads back to the problem of self-knowledge.

If we are to believe things because doing so will make us better it seems that we need some idea of what "better" consists in. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Having some idea of what is better is not knowing what is better. It is an opinion or belief. He could be wrong:

... being careful lest in my eagerness I deceive both myself and yourselves at the same time, and depart like a bee leaving my sting behind.

It is the question of what is better that is at issue. It involves deliberation about opinions about what is best. At best we do our best.

The dialogues aim at different audiences. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes. I agree. But we disagree as to what is being said to whom.

Perhaps, but when it comes to communicating with one another it seems that Plato thinks we will always need images. — Count Timothy von Icarus

We do need images. There are different kinds of images and different uses. We need images not just to communicate but to think and reason. The images used by the mathematicians is a good example.

We need not determine whether there is such a thing as a perfect circle in order to make use of these images. In fact, Socrates points out that such questions do not even arise for them.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum