Comments

-

What makes nature comply to laws?Now the question is: are we in the position of these chicken or can we rely on being fed every day? — Pez

Knowing what will happen does not mean we know why it will happen

We are in the position of the chickens. For example, we have discovered that the equation can accurately predict the distance a free-falling object falls from a position of rest. This equation describes what will happen not why it will happen. Until we know why the equation is able to predict what will happen, we cannot know whether that one day the equation will no longer work.

If the chickens knew why they were being fed, they would know that one day the feeding would stop, and would be slaughtered together with 140,000 of their comrades every minute.. -

InfinityIt's not required that each concept, each abstraction itself corresponds to a particular concrete. — TonesInDeepFreeze

I appreciate your post.

Yes, the mind has a framework of concepts, such as beauty, infinity, pain, mountain, house, government, addition, multiplication, sky, salt, which we use to organise our concrete experiences.

On the one hand, for example, our concept of mountain refers to an abstract object, in that it does not refer to one particular mountain, but mountains in general. But on the other hand, there must be an intentionality to our concepts, in that the mind is not able to comprehend a concept without thinking about something concrete, whether a particular object, such as the Mont Blanc, a particular process, such as adding more height to a high hill or the particular word itself, "mountain".

That is not to say that each concept can only have one concrete instantiation, but rather each time I think of a mountain my concrete instantiation may be different, and different again for anyone else who thinks of a mountain.

My point is that I agree that it is not the case that an abstract concept corresponds to one particular concrete instantiation, but rather we can only understand an abstract concept by thinking of some concrete instantiation of it, which may be a concrete object (Mont Blanc), a concrete process (addition) or a concrete word ("mountain"). -

What makes nature comply to laws?Immanuel Kant presents us with a surprising and seemingly absurd alternative: we ourselves are the source of physical laws. Seemingly absurd, because we cannot influence the laws of nature. — Pez

It depends what the expression "the laws of nature" is referring to. It could be referring to "the laws of nature" existing as concepts within the human mind, or it could be referring to the laws of nature existing outside the human mind and independently of the human mind.

If the first, we can influence them because they exist within the human mind. If the second, there is the problem of how we can know about them if they exist outside the human mind and independently of the human mind. -

Infinity"Infinity of infinites" in natural language

In natural language, we know the meaning of the word "infinity", yet infinity is unknowable by the finite mind, meaning that "infinity" must refer to something knowable.

Something very large is knowable, such as the number of grains of sand on a beach, the number of water molecules in a glass of water or the number of people living in a city.

We are able to understand "Infinity" as like "the number of grains of sand on a beach".

Therefore, our understanding of "infinity" is not literal but rather as a figure of speech, specifically, a simile.

If "infinity" means "like the number of grains of sand on a beach", then the expression "an infinity of infinities" becomes an "like the number of grains of sand on a beach" of "like the number of grains of sand on a beach". This is ungrammatical

IE, in natural language, the term "infinty of infinites" is ungrammatical. -

InfinityWe can imagine things without a concrete instantiation. — Metaphysician Undercover

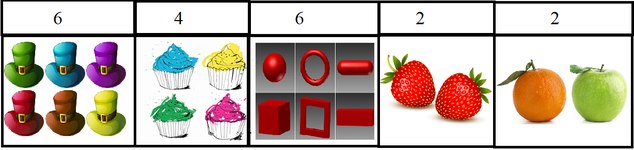

I find that hard to believe. How is it possible to imagine a unicorn by not picturing a unicorn? How is it possible to imagine the number 6 without picturing six things. How is it possible to imagine beauty without picturing something beautiful?

It is true that when I imagine a unicorn I could picture the word "unicorn", but this is still a concrete instantiation.

When you imagine a unicorn, if you are neither picturing a unicorn nor the word "unicorn", what exactly are you imagining? What exactly is your "Intentionality" directed at?

===============================================================================

We can imagine things without a concrete instantiation. That's how artists create original works, they transfer what has been created by the mind, to the canvas — Metaphysician Undercover

Problematic. If an artist, no matter whether Monet or Michaelangelo, could create something that hadn't existed before, this would be the same problem as to how something can come from nothing, the same problem as to how there be an effect without a cause.

An artist may reorganise existing parts, a blue line, a tree, a sky or a yellow mark, into a new whole, such as a painting of Water-lilies. An artist may change the relationship between parts that already exist, but the artists cannot create the parts out of nothing.

In fact, your challenge would be to find an artwork which included a part that did not already exist in some previous artwork.

The artist finds new relationships between existing parts. They don't create the parts.

The artist imagines new relationships between "concrete instantiations" of existing parts. The artist pictures new relationships between existing parts, and if successful, then applies them to the canvas. -

InfinityAnyway, the point is that this "picturing" does not require a "concrete instantiation", which I assume implies a physical object being sensed. — Metaphysician Undercover

I can only imagine a unicorn by picturing a unicorn. A picture requires a "concrete instantiation". A "concrete instantiation" can be on a screen or a piece of paper. Both a screen and a piece of paper are physical objects existing in the world. As physical objects in the world, I can sense them.

You can only imagine a unicorn if you know what a unicorn is. How can you know what a unicorn is without having first seen several "concrete instantiations" of it as physical objects in the world?

===============================================================================

But if "1=1" is meant to signify that the thing identified by "1" on the right side is the very same as the thing identified by the "1" on the left side, then it is not a mathematical expression. It is an expression of identity. — Metaphysician Undercover

Identity is a valid part of mathematics.

Wikipedia -Identity (Mathematics)

In mathematics, an identity is an equality relating one mathematical expression A to another mathematical expression B, such that A and B (which might contain some variables) produce the same value for all values of the variables within a certain range of validity. -

InfinityThe key point here, is that imagination does not require sensation of whatever it is that is imagined. — Metaphysician Undercover

I imagine a unicorn by picturing a unicorn.

How do you imagine a unicorn if you don't picture a unicorn?

===============================================================================

The point though, is that in the case where you used "=" to signify identity, it is not a mathematical usage. — Metaphysician Undercover

"1 = 1" is a mathematical expression. The expressions "Twain = Clemens" and "sugar = bad" are not mathematical expressions.

Similarly, the word "infinity" has one meaning in a formal set theory and a different meaning in everyday natural language

From Frege's "Context Principle", the meaning of "=" and "infinity" depend on their contexts. -

InfinityA "fictional object" is not an object,............. OED #1 definition of object "a material thing that can be seen or touched". — Metaphysician Undercover

A fictional object sounds like an object.

The OED notes "There are 14 meanings listed in OED's entry for the noun object, four of which are labelled obsolete" and then says "purchase a subscription".

The Merriam Webster includes "something mental or physical toward which thought, feeling, or action is directed".

I think Cervantes would have had great difficulty in writing "Don Quixote" without being able to describe objects.

===============================================================================

I suggest that your "position" is not consistent with common understanding. — Metaphysician Undercover

I agree that if one stopped one hundred people at random in the street, only a few would know about philosophical Monism.

Examples of modern philosophers who were monists include Baruch Spinoza, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Bertrand Russell (https://study.com)

===============================================================================

There is no such thing as a "concrete instantiation" of a concept......................show me where I can find a concrete instantiation of beauty, — Metaphysician Undercover

How can one learn a concept in the absence of a concrete instantiation of it?

For example, as a test, suppose you thought of a concept. In practice, how can you teach me its meaning without using concrete instantiations of it?

===============================================================================

Just point out this 6 to me, so i can go see it with my own eyes — Metaphysician Undercover

===============================================================================

I mean, you presented me with "a horse with a single straight horn projecting from its forehead", and i understand this image without seeing a concrete instantiation — Metaphysician Undercover

Exactly, you understand the concept using images.

===============================================================================

Furthermore, there is no practical advantage to designating "=" as meaning identical in the case of "1=1" — Metaphysician Undercover

There are two different cases.

The first a case of identity where the two 1's refer to the same thing. The second a case of equality where the two 1's refer to different things.

The practical advantage of using identity rather than equality is to distinguish two very different cases. -

InfinityOf course, that's known as fiction. — Metaphysician Undercover

"A mythical animal typically represented as a horse with a single straight horn projecting from its forehead" describes an object, even through the object is fictional.

In fact, from my position of Neutral Monism, all objects, whether house, London, mountain, government, the Eiffel Tower, unicorn or Sherlock Holmes are fictional, in that no object is able to exist outside the mind and independently of the mind.

===============================================================================

How do you think of a number as a natural concrete object? Are you talking about the numeral, or the group of objects which the numeral is used to designate, or what? — Metaphysician Undercover

The problem is, how does the mind understand an abstract concept, such as beauty, , ngoe, or the number 6?

My belief is that the mind cannot understand an abstract concept in isolation from concrete instantiations of it, in that, if I am learning a new word, such as "ngoe", it would be impossible to learn its meaning in isolation from concrete instantiations of it.

IE, I see no possibility of learning an abstract concept, such as "ngoe" or the number "6" without first being shown concrete examples of it.

===============================================================================

There is no such natural concrete object which the symbols refer to, in theory. only abstract concepts. — Metaphysician Undercover

If I wanted to teach you the meaning of the symbol "ngoe", which I know is a concept, how is it possible for you to learn its meaning without your first being shown particular concrete instantiations of it?

===============================================================================

And in application the concrete situation referred to by the right side of the equation is never the same as the concrete situation referred to by the left side. — Metaphysician Undercover

Given 1 and 1, if the second use of 1 refers to the same thing as the first use of 1, then the proper equation should be 1 = 1. The symbol "=" means identity

Given 1 and 1, if the second use of 1 refers to a different thing as the first use of 1, then the proper equation should be 1 + 1 = 2. The symbol "=" means equality.

Continuing:

Given a horse's body and a horse's head, as a horse's body is different to a horse's head, the proper equation should be horse's body + horse's head = horse

This raises the question as whether a horse as a whole is more than the sum of its parts, a horse's body and a horse's head.

Has the whole emerged from its parts, or is the whole no more than the sum of its parts?

IE, by knowing the parts, can I of necessity know the whole?

Referring back to Kant, by knowing the parts, for example, the number 5 and the number 7, can I of necessity know the number 12? -

InfinityIn your first question, "a person who can speak English" is a description, not an object. — Metaphysician Undercover

Can there be a description without an object being described?

Isn't "a person who can speak English" a description of the object (a person who can speak English)?

===============================================================================

It is not a true representation of how we use numbers, to think of a number as itself an object. — Metaphysician Undercover

The word "object" has different meanings. In mathematics, a mathematical object is an abstract concept (Wikipedia – Mathematical Object). In natural language, it can be something material perceived by the senses (Merriam Webster - Object).

For example, we can think of the number , the number and as abstract mathematical objects but cannot think of them as natural concrete objects.

However we can think of the numbers 1. 6 and 10 as not only abstract mathematical objects but also as natural concrete objects.

That raises the question as to how we are able to think of something that is abstract, disassociated from any specific instance (Merriam Webster – Abstract). For example, independence, beauty, love, anger, Monday, , and the number 6.

George Lakoff and Mark Johnson in their book Metaphors We Live By propose that we can only understand abstract concepts metaphorically, in that we understand the concept of gravity by thinking about a heavy ball on a rubber sheet.

Thereby, we understand the concept of independence by remembering the feeling of leaving a job we didn't like. We understand the concept of beauty by looking at a Monet painting of water-lilies. We understand the concept of infinity by thinking about continually adding to an existing set of objects. We understand the concept of by thinking about the number 1.414 etc etc. We understand the concept of 6 by picturing 6 apples.

IE, we can only understand an abstract concept metaphorically, whereby a word or phrase literally denoting one kind of object or idea is used in place of another to suggest a likeness or analogy between them (Merriam Webster – Metaphor). -

InfinityIf that is true, then even more reason why one would then consider the question in regard to mathematics. If it's meaningless in context C but defined in another context D, then it wouldn't make sense to say that then it is inapposite to context D. — TonesInDeepFreeze

That raises the interesting question that if an expression such as "infinite infinities" has no meaning in a natural language, the everyday spoken and written language used to describe the world around us, but does have meaning in the formal language of set theory, then what exactly is the relationship between a formal language such as set theory and the world around us? -

InfinityThe principal problem with set theory..............is that set theory is derived from a faulty Platonist premise, which assumes "mathematical objects" — Metaphysician Undercover

In a random web site is set a problem that can be solved by set theory:

In a group of 100 persons, 72 people can speak English and 43 can speak French. How many can speak English only? How many can speak French only and how many can speak both English and French?

Doesn't this problem, soluble by set theory, assume "objects", such as the object "a person who can speak English"?

If the number "1" does not refer to an object, what does it refer to?

along with its fantastic representation of "infinite" — Metaphysician Undercover

I would say that "infinite number" does not refer to an object, because unknowable by a finite mind, but does refer to a process along the lines of addition, which is knowable by a finite mind. -

InfinityThere are infinite sets that have sizes different from one another. — TonesInDeepFreeze

I take the OP as asking the question "are there an infinite number of infinities?"

The answer would depend on whether looked at from set theory or natural language.

Set Theory is a specific field of knowledge with its own rules, and as the Scientific American noted: As German mathematician Georg Cantor demonstrated in the late 19th century, there exists a variety of infinities—and some are simply larger than others.

However the terms infinity and infinite sets are also used in everyday language outside of set theory, such as "I have an infinity of problems" and "I have an infinite set of problems".

As the OP doesn't refer to the very specific field of "set theory", having its own particular rules, I think the OP should be considered as a problem of natural language.

Within natural language, the question "are there an infinite number of infinities" is meaningless, as not only is "an infinite number" unknowable, it follows that whether there is one or more infinite numbers must also be unknowable.

On the assumption that the OP refers to a problem in natural language, otherwise it would have specifically referred to "set theory", as it refers to that which is unknowable, although syntactically correct is semantically meaningless. -

InfinityOf course, but I'm saying that in context of sets in mathematics, 'infinity' as a noun invites misunderstanding, especially as it suggests there is an object named 'infinity' that has different sizes. — TonesInDeepFreeze

In the Merriam Webster dictionary infinity is classed as a noun, and within mathematics is the infinity symbol ∞. But as you say, this is problematic as it suggests that infinity is an object, such as a mountain or a table, which can be thought about. But in one sense this is impossible, as it impossible for a finite mind to know something infinite, where infinity is an unknowable Kantian "ding an sich" ("thing in itslef").

So what does the word "infinity" refer to, if not a noun inferring an object?

As the Wikipedia article on Infinity writes: Infinity is a mathematical concept, and infinite mathematical objects can be studied, manipulated, and used just like any other mathematical object.

As Literature as a noun refers to the study of books, perhaps Infinity as a noun refers to the study of infinite sets. Both Literature and Infinity are nouns, but refer to a process, not the intended conclusion of the process. This makes sense, as processes are comprehensible to finite minds. A finite mind can comprehend the process of adding to an existing set, even if not able to comprehend the eventual conclusion of continually adding to an existing set .

IE, "infinity" is a noun and refers to a process rather than any conclusion of that process. -

Infinity'infinity' is not an adjective. — TonesInDeepFreeze

True, infinite is an adjective and infinity is a noun

But it can get complicated.

Music fills the infinite between the two souls - Rabindranath Tagore

Infinity pencil with eraser - Amazon -

InfinityIf that is the case, then it seems barmy to talk about different size of the infinite sets. — Corvus

There cannot be different sizes of infinite sets

As you say: "Infinity is a property of motion or action..............Infinite number means that you keep adding (or counting whatever) what you have been adding (or counting) to the existing number"

What does "infinite set" refer to?

It cannot refer to an object, an infinite set, as comprehending an infinite set is beyond the ability of a finite mind. It can only refer to the process of being able to add to an existing set.

In other words, "infinite set" refers to "a set that can be added to", where "that can be added to" qualifies the object "a set".

As a "set" is an object it can have a size, and therefore there can be different sizes of sets.

However, as the qualifier "that can be added to" is not an aspect of the size of the set, whilst the expression "different sizes of sets" is grammatical, the expression "different sizes of infinite sets" is ungrammatical.

What is infinity

On the one hand we have the concept of infinity within the symbol ∞, but on the other hand a finite mind cannot comprehend an object of infinite size. So what does our concept of infinity refer to?

As the Wikipedia article Extended Real Number Line notes, the infinities are "treated" as actual numbers, not that the infinities are actual numbers.

As our concept of infinity cannot refer to an object, as comprehending an infinite number of things is beyond the ability of a finite mind, it can only refer to the process of adding to an existing number of things until it is not possible to add any more, which can be comprehended by a finite mind.

IE, "infinity" refers to a process not an object. -

InfinityInfinity is a property of motion or action — Corvus

I agree. "Infinite" is a property attached to an object, such as "large house" or "infinite number".

As "large" doesn't exist as an object, "infinite" doesn't exist as an object.

As I wrote before: ""infinity" as an adjective means something along the lines "any known set of real numbers can be added to"". -

InfinityCan there be infinite infinities?

Can there be an infinite set of (infinite set of numbers)?

The word "infinite" is not a noun but an adjective qualifying the noun "set".

Therefore, there can be infinite infinities because the word "infinity" is an adjective. -

Infinitydoes that mean that there are infinitely infinite infinitely infinite infinitely infinite infinitely infinite infinitely… (etc.) infinities? — an-salad

Hopefully this doesn't contradict what @TonesInDeepFreeze has said. It seems that if the word "infinity" was being used as a noun, then yes, there would be an infinite number of infinities. However, the word "infinity" is not being used as a noun, but rather is being used as an adjective, in which case there is only one infinity. IE, "infinity" as an adjective means something along the lines "any known set of real numbers can be added to". -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?But he is not denying the outside empirical world where you see all the daily objects and interact with them. — Corvus

There are several things in your posts that I don't agree with, but as I am off on holiday, I won't be able to tackle them.

However, I think you are misusing the term "Empirical World".

The IEP article Immanuel Kant: Metaphysics differentiates between an "empirical world" in the mind and a "mind-independent world" outside the mind

Kant responded to his predecessors by arguing against the Empiricists that the mind is not a blank slate that is written upon by the empirical world, and by rejecting the Rationalists’ notion that pure, a priori knowledge of a mind-independent world was possible. Reason itself is structured with forms of experience and categories that give a phenomenal and logical structure to any possible object of empirical experience. These categories cannot be circumvented to get at a mind-independent world, but they are necessary for experience of spatio-temporal objects with their causal behaviour and logical properties. These two theses constitute Kant’s famous transcendental idealism and empirical realism.

IE, the "Empirical World" is the world as perceived via the senses. That we may perceive tables and chairs in this "Empirical World" does not of necessity mean that tables and chairs exist in a "Mind-Independent World". -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?So the indirect realist believes that what we can't see is what is real? — Wayfarer

Not necessarily. Just because I cannot see a unicorn doesn't mean that I think unicorns are real.

From Wikipedia Direct and Indirect Realism

Indirect realism is broadly equivalent to the scientific view of perception that subjects do not experience the external world as it really is, but perceive it through the lens of a conceptual framework.

Direct realism postulates that conscious subjects view the world directly, treating concepts as a 1:1 correspondence.

I see the colour red, yet the colour red doesn't exist outside my perception of it. I do have, however, the fundamental belief that there is something in the world that caused me to perceive the colour red.

My seeing the colour red is a real experience, and I believe that there is also a real something in the world that caused my seeing the colour red.

For example, you may feel a sharp pain in your hand caused by a bee sting. I don't think anyone would argue that the pain and the bee sting are the same thing and thereby interchangeable. Both are real, yet different things. One is the effect and the other is the cause. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?Isn't it fairly simple that our perceptual abilities, and also our intellectual abilities, are limited in some ways, so that what the world is outside of those bounds can't be known by us? — Wayfarer

Exactly. This is the point that Kant is making in the CPR, and as an Indirect Realist, something I totally agree with.

However, I don't think that the Direct Realist would agree with you. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?How many external worlds do you have, and which one is the real world? Why do you need more than one world? — Corvus

There are many uses for the word "world". There is the world of dance, the world of science, the world of literature, the world inside our minds, the world outside our minds, etc.

One word having several uses is in the nature of language.

What is real? Is the thought of a mountain any less real than the mountain itself?

===============================================================================

What is the unknowable Things in themselves that exist outside you exactly mean? What are they? — Corvus

Kant wrote in Prolegomena section 32:

"And we indeed, rightly considering objects of sense as mere appearances, confess thereby that they are based upon a thing in itself, though we know not this thing as it is in itself, but only know its appearances, viz., the way in which our senses are affected by this unknown something."

We perceive appearances, phenomena, in our senses. We may see the colour red, feel a sharp pain, taste something sweet, smell something acrid or hear a grating noise.

We have the fundamental belief that something caused these phenomena. But we don't perceive what caused these phenomena, we only perceive the phenomena.

The cause of the phenomena is irrelevant in our experience of the phenomena, in that whether the sharp pain was caused by a bee sting, a sewing needle or a thistle plays no part in the nature of our experience of a sharp pain.

The cause of the sharp pain can be called a Thing in Itself, and even if unknowable, has no bearing on the nature of the actual experience of a sharp pain. Even if we knew what the cause was, this would not change the phenomena that we had perceived.

===============================================================================

So Things-in-themselves exist outside you, but it also exists in your mind? Are they the same Things-in-themselves? Or are they different entities? Are they visible or audible to you? Can you touch them? If they are not perceptible, then how do you know they actually even exist? — Corvus

My belief is that Things in Themselves have an ontological existence outside us even if a particular Thing in Itself is unknowable.

Kant uses Transcendental Reasoning on what we do know, appearances, to conclude that Things in Themselves must exist outside us.

Therefore, "Things in Themselves" have an ontological existence outside us, and they exist as thoughts inside us.

There are many things outside us that are not directly perceptible through the senses yet we reason exist. For example, gravity. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?Now the question goes back to Thing-in-itself. Is the Thing-in-itself something in the mind or does it exist outside of the mind? If outside, then would it be in the external world, or some other world totally separate from the external world? — Corvus

It depends what you mean by "external world". There is the external world that I perceive as Appearance, and there is the external world outside me that I cannot perceive that is causing these Appearances.

Kant wrote in B276:

"The mere, but empirically determined, consciousness of my own existence proves the existence of objects in space outside me."

Kant wrote in Prolegomena section 32:

"And we indeed, rightly considering objects of sense as mere appearances, confess thereby that they are based upon a thing in itself, though we know not this thing as it is in itself, but only know its appearances, viz., the way in which our senses are affected by this unknown something."

To my understanding of Kant, Appearances are affected by unknowable Things in Themselves that exist outside me.

However, as we can also think in general terms about Things in Themselves using Transcendental Reasoning on Appearances, thoughts about Things in Themselves exist in the mind. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?I do believe in only one world i.e. the physical world. I was asking about the external world in the Refutation for the Idealist you quoted. — Corvus

In B276 Kant refers to objects existing outside any human observer: "The mere, but empirically determined, consciousness of my own existence proves the existence of objects in space outside me."

You say that you see only one world, it is empirical, it is physical, it is external, it is not internal and it is not Mind-Dependent.

Are you:

An Indirect Realist who believes that the objects they see are only a representation of different objects that exist outside the observer in a non-mental world?

A Direct Realist who believes that the objects they see are the same objects that exist outside the observer in a non-mental world?

A Berkelian Idealist who believes that the objects they see are the same objects that exist outside the observer in a mind?

A Solipsist who believes that the objects they see only exist inside their own mind? -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?How does one know one's own existence "determined in time" without yet being sure of the external world? — Corvus

I assume you know your own existence within time, yet you don't seem to believe in an external world.

As you wrote:

===============================================================================I don't see it anywhere. Even with binoculars, telescope and magnifying glasses and microscopes, there is no such a thing as a Mind-independent world. There is just the empirical world with the daily objects I see, and interact with. That is the only world I see around me. Nothing else. — Corvus

Should the indirect realist not check the argument of the Refutation for the Idealism for any logical obscurity before accepting it? — Corvus

I'm sure they do. I know I have.

===============================================================================

It would be likely to be a biased opinion. It is better to look at the original work first, and then various other commentaries rather than just relying on one 3rd party commentary source. — Corvus

As Kant's philosophy is extremely complex and notoriously difficult to understand, I think the sensible approach is first to read various commentaries and then look at the original material. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?You cannot prove the existence of the objects in space outside of you by simply saying you are conscious of your own existence. — Corvus

In B276, Kant starts his proof with "I am conscious of my existence as determined in time."

He doesn't start his proof with "I am conscious of my existence".

===============================================================================

Not contradictory, but not making sense either. — Corvus

Kant's Transcendental Idealism and Refutation of Idealism B276 make sense to an Indirect Realist but perhaps not to a Direct Realist.

===============================================================================

Do you have the CPR reference for backing that points up? No Wiki or SEP, but CPR. — Corvus

For posts on the Forum, the SEP as source information is more than adequate.

Welcome to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (SEP), which as of Summer 2023, has nearly 1800 entries online. From its inception, the SEP was designed so that each entry is maintained and kept up-to-date by an expert or group of experts in the field. All entries and substantive updates are refereed by the members of a distinguished Editorial Board before they are made public. Consequently, our dynamic reference work maintains academic standards while evolving and adapting in response to new research. — https://plato.stanford.edu/about.html -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?You seem to think a world is some logically reasoned object. — Corvus

The Empirical World inside us we know through our sensibilities. The Mind-Independent World outside us we know through Transcendental Reasoning about the Empirical World inside us. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?A photograph is to show visual image, not the form of reason. It is nonsense to say that a photo can only show the form of reason. — Corvus

The Mind-Independent world can only be known using transcendental reason.

Reasoning is a logical connection between several strands of an argument, for example, the syllogism. A syllogism has the same form, in which a conclusion is drawn from two premises, regardless of its content.

For example, i) all men are mortal, Socrates is a man, therefore, Socrates is mortal ii) all dogs are animals, all animals have four legs, therefore all dogs have four legs.

As a syllogism can only have content when its form is complete, reason can only have content when its logical form is complete.

A single photograph as a single premise is only one part of a logical sequence within a reasoned argument, and as its logical form is incomplete, it cannot be said to have content.

This is why a single photograph cannot show a Mind-Independent World, as knowledge about a Mind-Independent World requires Transcendental Reason, and reason in order to have content requires a complete logical form. A single photograph as a single premise cannot have the necessary content for a Transcendental Reason as it is an incomplete logical form.

===============================================================================

In that case, would it be the case that you have been mistaken Kant's refutation of Idealism as Kant's TI? — Corvus

No.

From the Wikipedia article Transcendental Idealism

Transcendental idealism is a philosophical system founded by German philosopher Immanuel Kant in the 18th century. Kant's epistemological program is found throughout his Critique of Pure Reason (1781). By transcendental, Kant means that his philosophical approach to knowledge transcends mere consideration of sensory evidence and requires an understanding of the mind's innate modes of processing that sensory evidence.

In his Refutation of Idealism is his Theorem "The mere, but empirically determined, consciousness of my own existence proves the existence of objects in space outside me" B276.

These are not contradictory positions.

===============================================================================

In that case, should it not be a representation of the empirical world in your mind, rather than an internal world inside you? — Corvus

Of course, that's why in our internal world is a representation of the external world.

===============================================================================

As an aside, the Thing in Itself has nothing to do with God, the soul or freedom. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?There is only one world called the empirical world, and it is outside the mind. Appearance is from the empirical world....................When I see a book in front of me, it is via the appearance or phenomenon from the object (the book) in the empirical world (outside of the mind).................. The physical objects in the empirical world also continue to exist through time.................There is no such thing as an internal world. In your mind, there are only perceptions. — Corvus

I wrote that there are different "Worlds". One exists within the mind, an "Empirical World", and the other exists outside the mind, a "Mind Independent World"

From the Merriam Webster Dictionary, "empirical" means i) originating in or based on observation or experience, ii) relying on experience or observation alone often without due regard for system and theory.

"Empiricism" means i) the practice of relying on observation and experiment especially in the natural sciences ii) a tenet arrived at empirically.

So far, the word "empirical" refers to what exists in the mind rather than what exists outside the mind, inferring that an "Empirical World" also refers to what exists in the mind rather than what exists outside the mind,

The SEP article on Rationalism vs Empiricism also distinguishes between an external world and an internal world

The dispute between rationalism and empiricism takes place primarily within epistemology, the branch of philosophy devoted to studying the nature, sources, and limits of knowledge. Knowledge itself can be of many different things and is usually divided among three main categories: knowledge of the external world, knowledge of the internal world or self-knowledge, and knowledge of moral and/or aesthetical values.

You say that there is only "one world", and in this "one world" physical objects continue to exist through time. IE, whether one million years ago or one million years into the future. But we know that one million years ago there were no humans, meaning that in this "one world" you are referring to, humans are not a necessary part.

So how can this "one world" be an "empirical world" if humans are not necessarily there to observe it? -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?I am not sure if a philosophical topic which is totally severed from the Empirical world has a meaning. Are you? — Corvus

The Empirical World is the world of Phenomena, and the Mind-Independent World is the world of Things in Themselves.

I am sure that the Mind-Independent World is of philosophical interest.

Whether Kant intended the (negative) noumena as part of the Empirical world or the Mind-Independent World is ambiguous. Sometimes he treats the noumenon as a part of the Empirical World, and sometimes he treats the noumenon as part of the Mind-Independent World. In classical philosophy, Plato etc, the noumenon is part of the Empirical World.

From Wikipedia Noumenon

In Kantian philosophy, the noumenon is often associated with the unknowable "thing-in-itself" (German: Ding an sich). However, the nature of the relationship between the two is not made explicit in Kant's work, and remains a subject of debate among Kant scholars as a result.

As regards tables and chairs, we perceive them in our Sensibilities as Phenomena. If they exist as Things in Themselves in a Mind Independent Word then they are unknowable, meaning that we can never know whether they do or do not exist. But we do know about tables and chairs, meaning that our knowledge about them must have come from our Empirical World, as Ideas or Forms, ie as Noumena.

We can only know about Things in Themselves in general in a Mind Independent World using transcendental reasoning, in the same way as used by Kant in his Refutation of Idealism in B275. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?If you can see it, can you take a photo of a Mind-independent world, and upload here? — Corvus

As a Mind-Independent World can only be known by transcendental reason, and as a single photograph can only show the form of reason and not its content, a single photograph can never show a Mind-independent World.

===============================================================================

This thread is for reading Kant's CPR. Why try to show Berkeley's Idealism is incorrect? — Corvus

Kant refers to Berkelian Idealism in B275, which is part of his purpose in the Refutation of Idealism.

===============================================================================Idealism (I mean material idealism) is the theory that declares the existence of objects in space outside us to be either merely doubtful and indemonstrable, or else false and impossible; the former is the problematic idealism of Descartes, who declares only one empirical assertion (assertio), namely I am, to be indubitable; the latter is the dogmatic Idealism of Berkeley, who declares space, together with all the things to which it is attached as an inseparable condition, to be something that is impossible in itself, and who therefore also declares things in space to be merely imaginary.

In summary how did you manage to cram in the whole universe into inside your mind? — Corvus

Because a "mountain" as a representation in the Empirical World within the mind is different in kind to a "mountain" weighing one billion tonnes in a Mind-Independent World outside the mind. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?Even with a binoculars, telescope and magnifying glasses and microscopes, there is no such a thing as a Mind-independent world.............If you can see it, can you take a photo of a Mind-independent world, and upload here? — Corvus

Even if I uploaded a photo of a Mind-Independent World, the Solipsist wouldn't believe it. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?Where is a Mind-independent world? — Corvus

All around us. It existed before us and will exist after us.

===============================================================================Again what is the point even talking about something which is unknowable? — Corvus

To show that Berkelian Idealism is incorrect.

In fact, for the day to day survival of humans, there is no necessity to know more than what is perceived in our Empirical World of Phenomena. Any transcendental thought about a Mind-Independent World is out of philosophical interest only.

===============================================================================

If it was unknowable, then how did you know it was unknowable? — Corvus

Kant wrote that Appearances are based on Things in Themselves, even though Things in Themselves are unknown.

And we indeed, rightly considering objects of sense as mere appearances, confess thereby that they are based upon a thing in itself, though we know not this thing as it is in itself, but only know its appearances, viz., the way in which our senses are affected by this unknown something. — Prolegomena, § 32 — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thing-in-itself

Kant uses a Transcendental Argument in the Refutation of Idealism to prove his Theorem that Things in Themselves exist, even though what they are is unknown.

"The mere, but empirically determined, consciousness of my own existence proves the existence of objects in space outside me." B276 -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?No one was claiming Kant said the Thing-in-itself, something that is knowable. — Corvus

When I see the book in front of me, I know the book. I know it is in blue colured cover, it is a paperback book, the title of the book is "CPR" by Kant. I cannot be wrong on that. It is the truths I know about the book in front of me. I don't need to worry anything about Thing-in-itself book of CPR. There is no such thing as Thing-in-itself CPR book, but there is a CPR book in front of me. — Corvus

All this is true, in that you see the book in your Empirical World, the world that exists as Appearance in your Sensibilities. The world as Phenomena.

However, what you are not seeing is any world outside these Phenomena.

In a world outside these Phenomena are Things in Themselves, which are unknowable, and as unknowable, cannot even be thought about.

Even if books existed in a Mind-Independent world, as Things in Themselves they would be unknowable, and being unknowable, we couldn't even know whether they existed or not.

In Kant's Refutation of Idealism, he proposes the Theorem in B276: "The mere, but empirically determined, consciousness of my own existence proves the existence of objects in space outside me."

Yes, Kant as a believer in Realism does believe that a Mind-Independent World exists outside us, and within this Mind-Independent World are objects in space, but we only know that there are objects as a generality, we don't know what these objects are in particular

B279 – Here it had to be proved only that inner experience in general is possible only through outer experience in general.

We may know in general that Things in Themselves exist in a Mind-Independent World, otherwise we couldn't be discussing them, but that does not mean we can know individual Things in Themselves.

We may know the book in front of me in my Empirical Word, but we cannot know if there is a Book in a Mind-Independent World, as that would be a Thing in Itself. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?Meaning of "Empirical World"

Does the Empirical World exist within Appearances or does it exist the other side of these Appearances, whatever is causing these Appearances?

There are different "Worlds". One exists within the mind and the other exists outside the mind, independent of the mind.

There are two meanings of the word "empirical", i) a person's subjective experience and ii) exterior, objective data (Psychology Today – Gregg Henriques)

"Empirical Realism" is a term coined by Kant in the CPR. On the one hand "Empirical" because it gives the mind an active role in the cognition of empirical objects, an aspect of epistemology in establishing a subjective empirical reality. On the other hand, "Realism", endorsing the view that there is a world that exists outside and independent of the human mind. (Paul Abela Empirical Realism).

In his Theorem for the Refutation of Idealism in B276, Kant argues that objects exist in space outside the mind

The mere, but empirically determined, consciousness of my own existence proves the existence of objects in space outside me.

The IEP article Immanuel Kant: Metaphysics differentiates between an "Empirical World" in the mind and a "Mind-independent World" outside the mind

Kant responded to his predecessors by arguing against the Empiricists that the mind is not a blank slate that is written upon by the empirical world, and by rejecting the Rationalists’ notion that pure, a priori knowledge of a mind-independent world was possible. Reason itself is structured with forms of experience and categories that give a phenomenal and logical structure to any possible object of empirical experience. These categories cannot be circumvented to get at a mind-independent world, but they are necessary for experience of spatio-temporal objects with their causal behaviour and logical properties. These two theses constitute Kant’s famous transcendental idealism and empirical realism.

In summary, there is an "Empirical World" inside the mind, within Phenomena, within Appearances, within the Sensibilities and within the Senses and there is also a "Mind-independent World" outside the mind. -

Anyone care to read Kant's "Critique of Pure Reason"?There are different interpretations on this point. — Corvus

Kant wrote that we cannot have knowledge of a Thing in Itself. From Wikipedia Thing-in-itself

And we indeed, rightly considering objects of sense as mere appearances, confess thereby that they are based upon a thing in itself, though we know not this thing as it is in itself, but only know its appearances, viz., the way in which our senses are affected by this unknown something.— Prolegomena, § 32

Do you have a reference that says that Kant believes that it is possible to have knowledge of Things in Themselves?

===============================================================================

Things-in-themselves are for the objects we have concepts, but not the matching physical objects in the empirical world. We can think about it via concepts, but we don't see them in the phenomena. They belong to Thing-in-itself. — Corvus

You are referring to (negative) noumena, not Things in Themselves.

===============================================================================

If you believe in the existence of invisible particles and forces in space and time, then why do you deny the existence of the physical objects such as the bent stick in the empirical world?

If you had a single particle of the bent stick, would you say that is a part of the bent stick, and it is a stick?

In the absence of humans, sounds a condition that you must clarify before progressing further.

Where does "if something cannot be judged" come from? — Corvus

The discussion goes back to the question of whether, when we perceive a stick in our sensibilities, are we also perceiving the same object external to us in the world. This is something that the Direct Realist would argue is the case. Kant's position is not that of the Direct Realist.

You are still seeing an object external to you when you see the bend stick in the water jug. — Corvus

Do objects such as "sticks" exist in the empirical world?

In the empirical world are simples.

In the presence of humans, humans may name one particular set of simples "stick". This creates the object "stick", meaning that objects such as "sticks" do exist in the empirical world, but they only begin to exist after being named.

In the absence of humans, as naming is not possible, objects such as "sticks" cannot be created, meaning that objects such as "sticks" cannot exist.

RussellA

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum