Comments

-

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?Can’t possibly disagree. I guess someone in Chalmer’s role *has* to couch it in those terms to maintain some kind of credibility for the mainstream audience. Actually I’ve been reading a bit about David Chalmers, including an interview with him - he’s married to another academic, who has two PhDs; he was a Bronze Medallist at the International Mathematics Olympiad before becoming a philosopher; his mother ran a spiritual bookstore. Overall, it sounds he has one helluva life. Oh, and overall I far prefer him to Jacques Derrida. :-)

-

The Merely RealIt might be helpful to include an example of Proust's prose or perhaps some aphorisms in which this idea is articulated. I've never wrestled with Proust but I understand his major work is 7 volumes of rather dense literature, comparable to James Joyce and other heavyweights of the era.

And if reality can be merely real, can something else can be more than real? — Pantagruel

Without reference to Proust, I would venture that there a distinction can be made between what is real and what is merely existent. I interpret the major philosophical traditions (in which I don't include a great deal of modern philosophy) as the attempt to discern this distinction. Very briefly, the domain of existence is the phenomenal realm, the Buddhist realm of 'name-and-form', the perpetual flux of Heraclitus, the māyā of the Bhagavad Gita. Within this realm there is no ultimate satisfaction or peace to be found, because all is perishing, transient and ultimately empty. (And as I say, I don't know if Proust was intuiting this.) -

Murphy's law: "Anything that can go wrong will go wrong." Does this apply to life as well?Presumably the Original Poster thinks his thread has gone wrong.....

-

Joe Biden (+General Biden/Harris Administration)The Trump and Biden classified documents cases are very different.

Trump took documents as trophies of his time in office. Even when asked to return them, he dissimulated and obfuscated. He had his lawyers sign a statement that they had all been returned, when they hadn’t been. He stored the documents with others including magazines and personal correspondence, in non-secure rooms in close proximity to many casual visitors. He boasted even after the FBI raid that the documents were his personal property and besides he could de-classify them just by thinking about it.

The documents in Biden's possession with stored with other archival material from his time in office as Senator and Vice President. His own lawyers made the discovery, disclosed it as soon as it was made, and then continued an archive search to ensure the process was completed, turning up some more documents. It was clearly a case of adminstrative oversight, and I'm sure if there is a penalty for it, Biden will own up to it.

Sure, it's a 'people in glass houses' kind of thing, but the differences ought to be obvious.

As for Trump 'making peace with tyrants', who can forget the scene at the Helsinki summit when Trump stood on stage with Vladiimir Putin and said he valued his word over that of his own intelligence service. Or that he and Kim Jong Un were in love. Dictators and demagogues were the only people Trump ever professed public admiration for, because they were role models - they were who he wanted to be, but he had neither the guts nor cunning to pull it off, though not through want of trying. Something all Americans ought to be grateful for. -

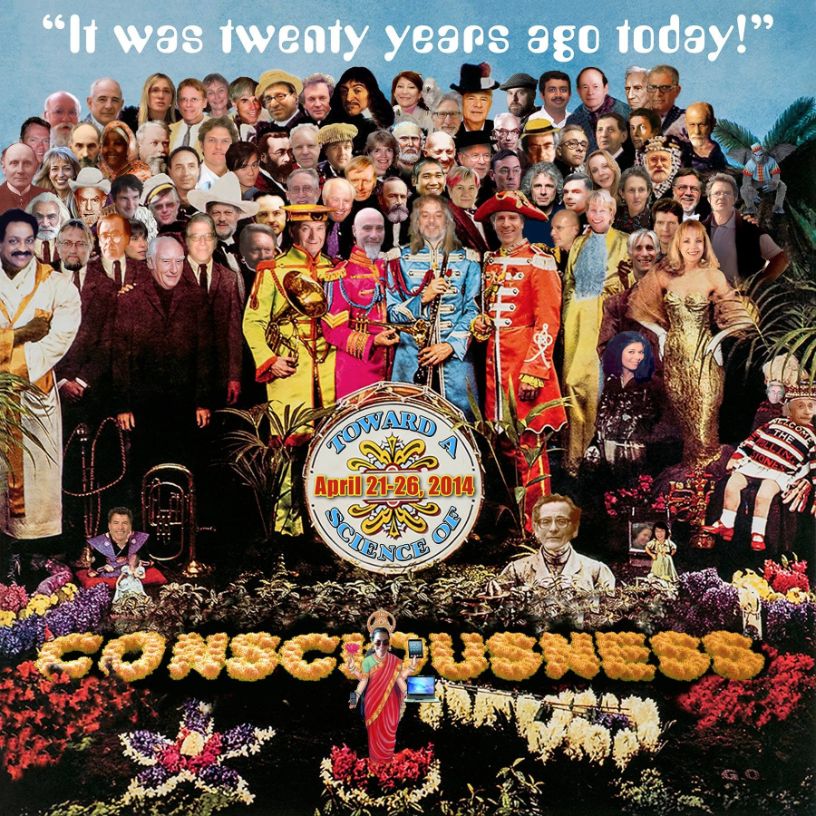

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?All fair points. I agree that Chalmers himself is not a phenomenlogical analyst. But I think the philosophical dimension, however articulated, is what is easily lost sight of in all these debates (as the desultory nature of much of this thread illustrates.) Furthemore, Chalmers is part of a kind of new wave in 'consciousness studies' that is far more open to, shall we say, alternative philosophical models, than the diehards of analytical philosophy (as illustrated in this memorable poster for the 20th Anniversary Consciousness Studies conference:

From here https://consc.net/pics/tucson2014.html) -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?I read Chalmers to be saying that consciousness could be investigated as a scientific phenomenon if the 'powerful methods' stopped insisting upon reducing it into a mechanism that excludes the need for a 'subject.'. — Paine

But I agree - that's a different way of making the same point. What is the name for the human subject? Why, that is 'a being'. And the failure to grasp this fundamental fact is an aspect of what Heidegger describes as 'the forgetting of being'. I've had many a debate on this forum, some of them very bitter and acrimonious, because I claim that beings are fundamentally different from objects.

Elsewhere, Chalmers advocates, and Dennett dismisses as fantasy, the idea of a 'first-person science'. But, as has been pointed out, phenomenology was originally conceived by Husserl as a first-person science of consciousness.

So I disagree that my post 'looses sight' of Chalmer's point of departure. I'm simply saying that what he describes as 'the hard problem of consciousness' could be better depicted as the problem of the meaning of being. -

Descartes and Animal CrueltyWell, my philosophy has been hugely shaped by Buddhism (not to say I'm actually Buddhist). But empathy, 'fellow-feeling', the connectedness of all beings, the fact that all sentient beings are points on a single continuum of existence, are parts of their underlying view of reality. 'All beings tremble before death, knowing this the wise ('Arya') do not kill nor cause to kill', goes one verse of the Dharmapada.

-

Descartes and Animal CrueltyIt also radically illustrates a profound disconnection from reality, in my opinion. Instructive, considering the oversize role Descartes had in the formation of modernity.

-

Descartes and Animal CrueltyWell, sure. But nailing dogs to boards and flaying them alive to make a philosophical point is a whole other level of cruelty. Makes me appreciate Buddhism all over again.

-

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?So, in short, I want to question the idea that anything "holds up, absent us". This would be to say that there is no-thing absent the conception of thing, but that what remains would not be nothing at all. — Janus

:clap: This is very much the point I've been labouring (subject of my Medium essays.)

I will also re-iterate that I think the 'hard problem of consciousness' is not about consciousness, per se, but about the nature of being. Recall that David Chalmer's example in the 1996 paper that launched this whole debate talked about 'what it is like to be' something. And I think he's rather awkwardly actually asking: what does it mean, 'to be'?

(I've finally started reading some of Heidegger, and whilst I have not yet acquired a lot of knowledge about him, I do now know that his over-arching theme throughout his writings was 'the investigation of the meaning of being', and that he thinks this is something that we, as a culture, have generally forgotten, even though every person-in-the-street thinks it obvious. )

Anyway, Chalmer's selection of title is perhaps unfortunate, because it is quite possible to study consciousness scientifically, through the perspectives of cognitive science, experimental psychology, biology, neurology and other disciplines. But we can't study the nature of being that way, because it's never something we're apart from or outside of (another insight from existentialism.) In the case of the actual 'experience of consciousness', we are at once the subject and the object of investigation, and so, not tractable to the powerful methods of the objective sciences that have been developed since the 17th century. -

Convergence of our species with aliensI don't know if it's either/or. Maybe that just happens to be the options our particular cultural situation forces us to choose from. In any case, the byline on the panspermia site is simply that 'life comes from life'.

-

Convergence of our species with aliensThe idea that ‘life is chemistry plus information’ implies that information is ontologically different from chemistry, but can we prove it? Perhaps the strongest argument in support of this claim has come from Hubert Yockey, one of the organizers of the first congress dedicated to the introduction of Shannon's information in biology. In a long series of articles and books, Yockey has underlined that heredity is transmitted by factors that are ‘segregated, linear and digital’ whereas the compounds of chemistry are ‘blended, three-dimensional and analogue’.

Yockey underlined that: ‘Chemical reactions in non-living systems are not controlled by a message … There is nothing in the physico-chemical world that remotely resembles reactions being determined by a sequence and codes between sequences’ .

Yockey has tirelessly pointed out that no amount of chemical evolution can cross the barrier that divides the analogue world of chemistry from the digital world of life, and concluded from this that the origin of life cannot have been the result of chemical evolution. This is therefore, according to Yockey, what divides life from matter: information is ontologically different from chemistry because linear and digital sequences cannot be generated by the analogue reactions of chemistry.

At this point, one would expect to hear from Yockey how did linear and digital sequences appear on Earth, but he did not face that issue. He claimed instead that the origin of life is unknowable, in the same sense that there are propositions of logic that are undecidable. This amounts to saying that we do not know how linear and digital entities came into being; all we can say is that they were not the result of spontaneous chemical reactions. — Marcello Barbieri, What is Information?

I do understand, however, that abiogenesis will remain an article of faith for most people, as any alternative will offend their belief system. -

Convergence of our species with aliensYou should investigate panspermia. 'Panspermia (from Ancient Greek πᾶν (pan) 'all ', and σπέρμα (sperma) 'seed') is the hypothesis, first proposed in the 5th century BCE by the Greek philosopher Anaxagoras, that life exists throughout the Universe, distributed by space dust, meteoroids, asteroids, comets, and planetoids, as well as by spacecraft carrying unintended contamination by microorganisms.'

It was championed by the late Fred Hoyle and colleague Chandra Wickramasingha in their book The Intelligent Universe. It is not generally accepted by scientists because it's, you know, pretty far out, but the idea has always appealed to me. The image that sticks is that of comets as sperm and potentially fertile planets as ova. These planets are seeded, presumably with DNA, and then evolution takes its course. There's a website here https://www.panspermia.org/ created by a Brig Klyce that argues the case. -

Descartes and Animal CrueltyI had previously read that Descartes believed that animals were automatons devoid of consciousness, but I didn't realise he would have taken it to these extremes.

Much of the never-ending debate about 'qualia' and consciousness can be traced back to the consequences of Cartesian dualism. As can the 'cartesian anxiety' which is subject of philosophical debate. Previously I had always admired Descartes - he was the subject of the first philosophy course I ever attended at University as 'the first modern philosopher'. But I'm now beginning to wonder whether he actually might have closer to an evil genius. It would explain something of what is wrong with the world today. -

Evolution and the universeCan any animals be described as morally worse, or morally better?

-

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?The Sun is 93 million miles away from Earth, the distance remains a fact, irrespective of us. — Manuel

Realism assumes that the world is just so, irrespective of whether or not it is observed. It may be a sound methodological assumption but it doesn't take into account the role of the observing mind in the establishment of scale, duration, perspective, and so on.

So, I question the notion that there are facts that stand 'irrespective of us'. We can establish distances, durations, and so on, across a huge range of scales, from the microscopic to the cosmic, which we can be confident will remain just so even in the absence of an observer. But even that imagined absence is a mental construct. There is an implied viewpoint in all such calculations. This is thrown into relief in quantum physics, but it's true across the scale. We're used to thinking of what is real as 'out there', independent of us, separate from us, but in saying that, we don't acknowledge the fact that reality comprises the assimilation of perceptions with judgements synthesised into the experience-of-the-world. -

The possibility of fields other than electromagneticWhat I find intriguing is how a human - using reason - would achieve what the oysters did in that tank — Agent Smith

Just took delivery of the book from which that was excerpted, I might return with an update

Human Cosmos: A Secret History of... https://www.amazon.com.au/dp/1786894041?ref=ppx_pop_mob_ap_share -

What is your ontology?Ironically, that Empirical, tangible-results-oriented, understanding of "Reason" is common even on The Philosophy Forum, where we don't do anything remotely empirical. — Gnomon

What's the justification for a physicalist ontology? — Agent Smith

It's not complicated. There's broad consensus that religion and metaphysics are archaic, they haven't moved with the times, and are no longer relevant to life as it's lived now. By default, the only yardsticks we have are those provided by science. Of course there is an enormous variety of attitudes and views, but that is broadly true in secular cosmopolitan culture. Materialism as a philosophy arises mainly from attempt to apply scientific methods to philosophical problems, or to deny that there are philosophical problems that are not in scope for scientific method.

The entire truth/the true nature of reality has been proposed many times from many disciplines but never fully adopted or unanimously accepted, — Benj96

It's not a democratic question! And the fragmentation of worldviews is inevitable in the kind of culture we're in, with instantaneous mass communications available to everyone around the world. In that sense, everyone has to find their own truth, which doesn't necessarily mean something of their own invention. (Isn't that what Kierkegaard said?) In some ways, it has never been easier due to the abundance of information, but also it's never been harder, because of the number of apparently conflicting views.

Incidentally and apropros this thread, an excellent new article on Aeon.co on Karl Jaspers. -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical PlatonismI agree. That takes it to the realm of the meaning of words: reality. — jgill

Right. I was recommended a book by Fooloso4 - again, a very difficult read - but I found this snippet which exactly described my original intuition as to what the Ancients were seeking through mathematical knowledge:

Neoplatonic mathematics is governed by a fundamental distiction which is indeed inherent in Greek science in general, but is here most strongly formulated. According to this distinction, one branch of mathematics participates in the contemplation of that which is in no way subject to change, or to becoming and passing away. This branch contemplates that which is always such as it is and which alone is capable of being known: for that which is known in the act of knowing, being a communicable and teachable possession, must be something that is once and for all fixed. — Jacob Klein, Greek Mathematical Thought and the Origin of Algebra

Bertrand Russell remarks, in the History of Western Philosophy, in his chapter on Pythagoras, that it is this combination of mathematics and mysticism which distinguishes the Western philosophical tradition from the Asiatic. It is also, one could argue, why the 'scientific revolution' occured in the West (contentious claims, I know.)

This kind of insight goes back to the Platonist distinction between the 'unreliable' testimony of sense, and the (supposedly) apodictic certainty of rational or mathematical reason. Of course there's been a lot of water under the bridge since, but I still feel there's an element of truth which has been largely forgotten. That's the thread I've been following. -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical PlatonismI get it. After all, as Piggliuci says in that article, '“If one ‘goes Platonic’ with math, empiricism “goes out the window.” (If the proof of the Pythagorean theorem exists outside of space and time, why not the “golden rule,” or even the divinity of Jesus Christ?)"' And we certainly can't risk that, can we! Imagine the nonsense threads alone. (I did seek out and buy, at some expense, Brown's book Platonism, Naturalism, and Mathematical Knowledge, but it's a difficult read.)

-

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical PlatonismCarlos Rovelli appears in the article I mentioned when I re-started this thread.:

Rovelli [calls into] question the universality of the natural numbers: 1, 2, 3, 4... To most of us, and certainly to a Platonist, the natural numbers seem, well, natural. Were we to meet those intelligent aliens, they would know exactly what we meant when we said that 2 + 2 = 4 (once the statement was translated into their language). Not so fast, says Rovelli. Counting “only exists where you have stones, trees, people—individual, countable things,” he says. “Why should that be any more fundamental than, say, the mathematics of fluids?” — What is Math

It's fundamental because of the way the world is, because we are indeed embodied beings and the world is constrained to exist in certain ways. But according to this argument, there are no necessary facts, everything just happens to be the case - everything is in some basic sense arbitrary, it could just as easily be otherwise. This, I think, is ultimately a form of nihilism.

Elsewhere Rovelli appeals to the Buddhist philosopher Nāgārjuna to justify his 'relational quantum mechanics' but he neglects the ethical dimension of Nāgārjuna philosophy, without which it would indeed be merely nihilistic. Rovelli appears to interpret Nāgārjuna to be saying that 'nothing really exists', which is the common, but fallacious, charge made against Nāgārjuna and the Madhyamika generally. See Bernardo Kastrup's Here I Part Ways with Rovelli:

What Rovelli seems to be now saying is that, although the physical world is constituted of no more than relationships, there is no underlying, non-physical world to ground those relationships. This is problematic for a number of reasons. For one, it immediately runs into infinite regress: if the things that are in relationship are themselves meta-relationships, then those meta-relationships must be constituted by meta-things engaging in relationship. But wait, those meta-things are themselves meta-meta-relationships... You see the point. It's turtles... err, relationships all the way down. — Bernardo Kastrup -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical PlatonismAnd yet the concept of number would be incoherent without the prior construction of the concept of a multiplicity , which itself implies the concept of persisting self-identical empirical object. — Joshs

Of course, but I don't see any particular conflict with what I'm saying. I had the idea that arithmetic and geometry developed greatly with the establishment of the first agrarian cultures in the Nile delta and Fertile Crescent, used for calculating parcels of land and tallying grain harvests and the like.

(I'm quite interested in the basics of Husserl's philosophy of number but it appears daunting.) -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical PlatonismHi Streetlight. — Agent Smith

Long gone. I revived this thread because it was relevant to the point I was making elsewhere. Prior to that the last post was 4 years ago.

After crossing the river, one of them counted them, not counting himself — Agent Smith

"Materialism is the philosophy of the subject who forgets to take account of himself" ~ Arthur Schopenhauer.

My guess is your parable was intended to make this point. -

Evolution and the universeYou've two options for morality. Religiously based - hence we were created for a purpose. Or secular. In which case we weren't. — Bradskii

My case stands. -

Evolution and the universeSecular humanism is unavoidably conditioned by underlying prejudices, such as the idea that life is a consequence of blind physical laws. I've read a lot of the literature and it doesn't move me, although it has its place in civil society.

-

Evolution and the universeI've often heard Dawkins make comments to the effect that Darwinism is an awful social philosophy. What I haven't heard is any plausible suggestions for an alternative, and what sort of basis it might have. If, after all, we really are genetically programmed to behave a certain way, then what can we bring to bear on the human condition to improve it?

I'm guessing that Dawkins' answer will be along similar lines to Steve Pinker's - 'enlightenment values' and 'scientific rationalism'. And indeed they have a lot going for them, but behind them, what image of man are they built around? I'm also not going to propose an answer to that, but I don't see much hint of it in Dawkin's anti-religion polemics.

Philosophers and humanists are interested in what has been called, in 20th-century continental philosophy, the human condition, that is, a sense of uneasiness that human beings may feel about their own existence and the reality that confronts them (as in the case of modernity with all its changes in the proximate environment of humans and corresponding changes in their modes of existence).

Scientists are more interested in human nature. If they discover that human nature doesn’t exist and human beings are, like cells, merely parts of a bigger aggregate, to whose survival they contribute, and all they feel and think is just a matter of illusion (a sort of Matrix scenario), then, as far as science is concerned, that’s it, and science should go on investigating humans by considering this new fact about their nature.

And much of that is implicit, rather than stated upfront. -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical PlatonismApart from the fact that most mathematicians (including me) don't spend any time contemplating the possible Platonic nature of their subject, a more intriguing question is what makes a math subject or result "interesting"? — jgill

What made it interesting to me was the (I thought) simple observation: that numbers (and the like) are unlike phenomenal objects, in that they're not composed of parts (strictly speaking that is only prime numbers) and they don't come into, or go out of, existence (i.e. they're not temporally delimited.) So they exist on a different level, or in a different sense, to objects, all of which are composed of parts and temporally delimited. But then, the idea that there can be different levels of existence, or different senses of existence, turns out to be a metaphysical question.

This was the subject of my first post on the predecessor forum to this one. An excerpt from that was as follows:

I started wondering, this (question, i.e. reality of number) is perhaps related to the platonic distinction between 'intelligible objects' and 'objects of perception'. Objects of perception - ordinary things - only exist, in the Platonic view, because they conform to, and are instances of, laws. Particular things are simply ephemeral instances of the eternal forms, but in themselves, they have no actual being. Their actual being is conferred by the fact that they conform to laws. So 'existence' in this sense, and I think this is the sense it was intended by the Platonic and neoplatonic schools, is illusory. Earthly objects of perception exist, but only in a transitory and imperfect way. They are 'mortal' - perishable, never perfect, and always transient. Whereas the archetypal forms exist in the One Mind and are apprehended by Nous: while they do not exist they provide the basis for all existing things by creating the pattern, the ratio, whereby things are formed. They are real, above and beyond the existence of wordly things; but they don't actually exist. They don't need to exist; things do the hard work of existence.

And no, I don't think it's anything to do with the pursuit of maths as such. There are excellent mathematicians, I have no doubt, who are inclined towards a Platonist view - Roger Penrose and Kurt Godel being two - but there are doubtless very many who don't. And you don't have to know much about maths to understand the major issue, that being the reality of intelligible objects.

//I guess in hindsight that excerpt is a bit over the top. I hadn't planned it, I just sat down to say something and that is what I came up with. I still think it's OK, though.// -

Carlo Rovelli against Mathematical Platonism[transposed from Hard Problem thread]

But math doesn't depend on objects. — Manuel

Absolutely. And that it doesn't seem to depend on the universe, somehow. Utterly baffling. — Manuel

It's a question I'm very interested in. One point I've often raised is that numbers (and logical laws and so on) are not dependent on your or my mind, but can only be grasped by a rational intelligence. So they're mind-independent in the sense that they're the same for anyone, but mind-dependent in the sense they can only be grasped by an intelligence capable of counting. This clashes with the empiricist view that numbers (and the like) must be considered a product of the mind. It implies they are real but in a manner different to empirical objects of perception. And mainstream philosophy has no way to accomodate different kinds of real - for it, something is either real or it's not.

See the essay What is Math? in the Smithsonian magazine. James Robert Brown puts the Platonist argument for the reality of number. But the objections are that if numbers are not empirical objects, then you're opening the door to all kinds of 'mystical nonsense':

The idea of something existing “outside of space and time” makes empiricists nervous: It sounds embarrassingly like the way religious believers talk about God, and God was banished from respectable scientific discourse a long time ago.

Platonism, as mathematician Brian Davies has put it, “has more in common with mystical religions than it does with modern science.” ....

Massimo Pigliucci...was initially attracted to Platonism—but has since come to see it as problematic. If something doesn’t have a physical existence, he asks, then what kind of existence could it possibly have? “If one ‘goes Platonic’ with math,” writes Pigliucci, empiricism “goes out the window.” (If the proof of the Pythagorean theorem exists outside of space and time, why not the “golden rule,” or even the divinity of Jesus Christ?)

These objections speak volumes, in my opinion. -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?I've moved my reply to a thread on mathematical Platonism as it is a different question to 'the hard problem of consciousness'.

-

Essence and Modality: Kit FineI think I'm starting to get the point (although he lives up to his surname :-)

-

Essence and Modality: Kit FineIt was a nice little place. Not so much anymore. — Banno

My dear other hails from there. She has a number of bearded uncles resident there although none resembling Socrates. Anyway I think I am starting to see the point, thanks. -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?You could change the symbol to anything you want, but what the symbol represents would have to be constant. That's what is interesting!

-

What is your ontology?If you include the relation between the knower and the known, then we really have a triune process as Gurdjieff, Hegel and Peirce, in their different ways, have indicated. — Janus

:100: But you'd hardly cast them as representative of our culture at large. -

Essence and Modality: Kit FineI'm trying to understand the point that Kit Fine is making. As you posted the article, I thought you might cast a little light there. I haven't read the whole article but if we could get some clarity around this 'singleton Socrates' (must say, as a New South Welshman, the phrase made me laugh at first) it might help.

-

What is your ontology?That's why I call Reason : "the sixth sense", which is uncommon even among human animals. — Gnomon

The point about the understanding of reason in contemporary culture is that it tends to be strictly constrained by empiricism, meaning in effect that it must always be ultimately validated by experiential, third-person evidence - meaning, in effect, sensory experience enhanced through instruments and extrapolated mathematically. So when most people say 'reason' in effect they mean 'scientific reason' which operates within constraints that are rarely made the object of explicit awareness. Philosophers (or some philosophers) are well aware of this. -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?Can it be said that 2+2=4 was true prior to the universe and after its predicted collapse? That's difficult, but, the truth of this claim appears to be independent of the universe. — Manuel

i.e. 'true in all possible worlds'. -

Essence and Modality: Kit FineHere is the passage that @Caldwell referred to:

If I am right, there is more to the idea of real definition than is commonly conceded. For the activities of specifying the meaning of a word and of stating what an object is are essentially the same; and hence each of them has an equal right to be regarded as a form of definition*

My response is: so what? What is the point? -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?In human terms you might say reinforcement learning is about learning how you should make decisions so as to maximise the amount of pleasure you experience in the long-term. (Could you choose to make decisions on some other basis?) — GrahamJ

Do you mean, that hedonism is the only basis you see for an ethical philosophy? That there are no ends beyond pleasure?

In stating the hard problem this way, have I unwittingly signed up for transcendental or metaphysical realism? — GrahamJ

Based on what you've said, I think 'metaphysical realism' with a strong side-order of Skinnerian behaviourism.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum