Comments

-

What is the Nature of Intuition? How reliable is it?Welcome to Philosophy Forum.

I think of 'intuition' as 'knowing without knowing how you know', which I think is consistent with Bonjour's use. He claims intuition plays a crucial role in the epistemic justification of beliefs, serving as foundational sources of justification, providing immediate and basic support for our beliefs while also recognising that intuitions need to be critically examined and subjected to reflective evaluation to ensure their reliability and avoid potential errors.

In any case, I'm with Bonjour. I take it that he's arguing for a rationalist view which accepts that there are necessary truths. Harman's response seems like typical modern relativism, which basically depends on the hypothetical argument that 'anything can happen' with the implication that there are no necessary truths. The idea of other possible worlds is often cited in support of that view, with the view of reducing what seems necessary truths to contingencies which just happen to be true 'for us'.

Finally, how could you discern if an intuition were really 'a neuron circuit'? Presumably such a circuit will not be labelled 'intuition' so you would have to judge what the 'neuron circuit' encoded or implied or meant by evaluating the data. And any such judgement would be, well, a judgement, which relies on just the kind of intuitive insight that Bonjour is arguing for. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesThe familiar world of material objects becomes something quite alien once seen from a more properly objectified perspective, with its quantum fields and relativity — apokrisis

Indeed. One of the principle reasons materialism has fallen into disfavor.

Do you agree, then, that psychology, insofar as it is the science of consciousness, is in principle capable of the same degree of precision and objectivity as is physics? -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesWe infer things all the time without seeing them directly — T Clark

Of course. I acknowledged that we can infer that there are minds, but that the mind is not an object for us.

the Large Hadron Collider sends a bunch of particles into another bunch of particles, no one sees the actual collisions, they see readouts on a recording device. — T Clark

Right. And there is controversy about what these particles are, whether they're really particles or actually waves, or excitations in a field. Instrumentalists say, it doesn't matter, shut up and calculate.

But all of that is irrelevant to the question at hand. At least objects - a lump of matter, a marble or a bullet - can be described objectively. You and I can pick it up, weigh it, ascertain its attributes and qualities. But consciousness is nothing like that. You can say to me, I'm depressed, or I'm happy, and I will know what you mean, because I too am a conscious being, and I know what it is like to be conscious or happy, so I will infer that I feel the things that you feel. But none of those qualities are objectively real in the way that bullets or marbles are. I could put an object in a lunar lander and send it to the moon, but there is no way to pack and send a feeling, an emotion. It can only exist as a state of being, but what that being is, is precisely what eludes objective description.

Science – including psychophysics and cognitive neuroscience – can only address empirical givens by definition. — javra

FWIW, I'm in agreement, as I hope is also evident from what I've said above.

Useful crib on scientific method:

Modern science emerged in the seventeenth century with two fundamental ideas: planned experiments (Francis Bacon) and the mathematical representation of relations among phenomena (Galileo). This basic experimental-mathematical epistemology evolved until, in the first half of the twentieth century, it took a stringent form involving (1) a mathematical theory constituting scientific knowledge, (2) a formal operational correspondence between the theory and quantitative empirical measurements, and (3) predictions of future measurements based on the theory. The “truth” (validity) of the theory is judged based on the concordance between the predictions and the observations. While the epistemological details are subtle and require expertise relating to experimental protocol, mathematical modeling, and statistical analysis, the general notion of scientific knowledge is expressed in these three requirements.

Science is neither rationalism nor empiricism. It includes both in a particular way. In demanding quantitative predictions of future experience, science requires formulation of mathematical models whose relations can be tested against future observations. Prediction is a product of reason, but reason grounded in the empirical. Hans Reichenbach summarizes the connection: “Observation informs us about the past and the present, reason foretells the future.”

The demand for quantitative prediction places a burden on the scientist. Mathematical theories must be formulated and be precisely tied to empirical measurements. Of course, it would be much easier to construct rational theories to explain nature without empirical validation or to perform experiments and process data without a rigorous theoretical framework. On their own, either process may be difficult and require substantial ingenuity. The theories can involve deep mathematics, and the data may be obtained by amazing technologies and processed by massive computer algorithms. Both contribute to scientific knowledge, indeed, are necessary for knowledge concerning complex systems such as those encountered in biology. However, each on its own does not constitute a scientific theory. In a famous aphorism, Immanuel Kant stated, “Concepts without percepts are blind; percepts without concepts are empty.” — Edward Dougherty

At issue is the question of how this is applicable to the question of the nature of conscious experience (and remember, that is the question.) It may be asked, where is the rigour seen in scientific analysis, when it comes to the kind of first-person analysis that the objection is suggesting? David Chalmers does actually address this:

To explain third-person data, one needs to explain the objective functioning of a system. For example, to explain perceptual discrimination, one needs to explain how a cognitive process can perform the objective function of distinguishing various different stimuli and produce appropriate responses. To explain an objective function of this sort, one specifies a mechanism that performs the function. In the sciences of the mind, this is usually a neural or a computational mechanism. For example, in the case of perceptual discrimination, one specifies the neural or computational mechanism responsible for distinguishing the relevant stimuli. In many cases we do not yet know exactly what these mechanisms are, but there seems to be no principled obstacle to finding them, and so to explaining the relevant third-person data.

This sort of explanation is common throughout many different areas of science. For example, in the explanation of genetic phenomena, what needed explaining was the objective function of transmitting hereditary characteristics through reproduction. Watson and Crick isolated a mechanism that could potentially perform this function: the DNA molecule, through replication of strands of the double helix. As we have come to understand how the DNA molecule performs this function, genetic phenomena have gradually come to be explained. The result is a sort of reductive explanation: we have explained higher-level phenomena (genetic phenomena) in terms of lower-level processes (molecular biology). One can reasonably hope that the same sort of model will apply in the sciences of the mind, at least for the explanation of the objective functioning of the cognitive system in terms of neurophysiology.

When it comes to first-person data, however, this model breaks down. The reason is that first-person data — the data of subjective experience — are not data about objective functioning. One way to see this is to note that even if one has a complete account of all the objective functions in the vicinity of consciousness — perceptual discrimination, integration, report, and so on — there may still remain a further question: why is all this functioning associated with subjective experience? And further: why is this functioning associated with the particular sort of subjective experience that it is in fact associated with? Merely explaining the objective functions does not answer this question.

I think the moral is that as data, the first-person data are irreducible to third-person data, and vice versa. That is, the third-person data alone provide an incomplete catalog of the data that need explaining: if we explain only third-person data, we have not explained everything. Likewise, the first-person data alone are also incomplete. A satisfactory science of consciousness must admit both sorts of data, and must build an explanatory connection between them. — Can we construct a science of consciousness? David Chalmers

I think that this is what Edmund Husserl was proposing with his model of the 'phenomenological reduction', perhaps @Joshs might comment on that. -

The Argument from ReasonAgain, I'll reply to you, because dialoging with 180 is like talking to a snarky wall. — Gnomon

Totally hear you on that. But your use of the metaphors of information and information processing introduce many difficulties from a philosophical point of view. My own approach is more oriented around 'history of ideas' and understanding how ideas influence cultural dynamics and entrenched attitudes, leavened somewhat with my engagement with Buddhist praxis. I try and situate what I write against that context. I am not much in favour of 20th century Anglo-American philosophy which overall is oriented around scientific naturalism and armed to the teeth against anything suggesting idealism (although there is a healthy idealist strain in current culture also.)

(The) Materialistic worldview seems to be based on pragmatic scientific Reduction — Gnomon

I'll take a step back. How modern physicalism, naturalism or materialism evolved is, I think, not very difficult to discern. The watershed was René Descartes, and the confluence of his work with Newtonian physics and Galileo's cosmology. This sets up the modern worldview (bearing in mind we're now situated in a post-modern world, but I'll leave that aside for now.) The 'universal science' at the heart of this method, based on precise analysis of measurable attributes using Cartesian algebraic geometery and calculus, is the basis of the success of the modern scientific method. The famous Cartesian description of the mind as 'res cogitans', literally, 'a thinking thing', however, has had calamitous consequences, as it seemed very difficult to establish what, exactly, it means. Meanwhile, the concentration on the purely measurable and quantitative aspects of the universe in the discovery of modern scientific method provided many astounding breakthroughs. Within that context, scientific materialism is the consequence of attempting to apply the very successful methods deployed by science to the problems of philosophy (in the absence of any real insight into what those problems are.) That's it in a nutshell, as far as I'm concerned. (I think in all likeliood, phenomenology and existentialism is far nearer the mark than anglo-american philosophy, but I'm not well-schooled in that either.)

As regards mathematical platonism - I had a minor epiphany about that. It was simply this: that whilst every material object is composed of parts and has a beginning and an end in time, this does not apply to numbers and other mathematical objects (although later I realised that only prime numbers are strictly indivisible.) At the time of this realisation, I thought 'aha! This is why the ancients held mathematics in such high esteem: they're nearer the "unconditioned origin of being"'. And the fact that the intellect is able to grasp these ideas is evidence for a kind of dualism, although not of the Cartesian kind. (I've attempted to follow that thread through the labyrinth, but the subject matter is arcane and difficult, and demands a much greater knowledge of all the classical texts than I will ever have.)

One of my all-time favourite Buddhist texts was subtitled 'Seeking truth in a time of chaos'. Don't loose sight of the fact that modernity - actually, post-modernity - is chaotic. There's a lot of turmoil, vastly incompatible opinions and worldviews all jostling one another for prominence. Learn to live with it, but I recommend not trying to tame the waters. It's beyond any of us to to that. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesmind is never an object to us

— Wayfarer

This is certainly not true. There are more than seven billion human minds that are objects to us — T Clark

You never see anyone's mind. You can see their behaviour or hear what they say, but you never see the mind except for in a metaphorical sense.

I may not be able to treat my own mind solely as an object -- though I can surely take it also as an object -- but it's not obvious what the barrier is to me treating your mind as an object of my study, and since it is your mind, not mine, I can only take it solely as an object and never as subject. — Srap Tasmaner

Right. You can treat the mind as an object in a metaphorical sense: 'her mind was the object of my enquiry'; 'the subject's mental state was extremely confused'; 'that individual had a brilliant mind'; and so on. But mind itself is not an object, unlike any of the objects which you will see if you raise your eyes and glance around you. I think this is habitually overlooked or ignored, but it is the realisation behind both behaviourism and eliminative materialism which arise from a very similar insight: that the mind as such is not scientifically tractable in the sense that phenomenal objects are. -

The Argument from ReasonIs the concern overdetermination of the belief? — NotAristotle

Something like that. Put it this way: if a belief is a consequence of a brain condition, then it is not held on the basis of logical necessity. It is arguing that if our ability to reason logically is merely a result of physical processes, such as the firing of neurons, then there are no grounds to trust that our logical conclusions are valid. Our logical reasoning would be explained in terms of physical processes, undermining the sovereignty of reason. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesIs life something apart from the process of living? Does a verb need to be confused as a noun? — apokrisis

Very good question. Being is a verb, isn’t it? Doesn’t Aquinas have something to say about that? (quick google.) Aquinas argues that being (esse) is the act of existence itself. For him, existence is not just a quality or attribute that something possesses; rather, it is the act of being. In other words, being is not something static but an active and dynamic reality. (Not that I'm an Aquinas scholar.) -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesI wonder what a 'scientific explanation of consciousness' - or let's say 'mind' - is trying to actually explain. I mean, there are untold applications and benefits of science in cognitive and neuroscience, no question. But the scientific search for 'what is the mind?' will always be bedevilled by the epistemic split between knower and known, because in the case of mind or consciousness, we are what we are seeking to understand - mind is never an object to us. And I say there's a profound problem of recursion or reflexivity in the endeavour to understand it objectively, given in the Advaitin aphorism, 'the eye cannot see itself, the hand cannot grasp itself.'

What this means is that what we know of consciousness, we know because it is constitutive of our existence and experience. It appears as us, not to us. Realising that is itself a change in perspective - a meta-cognitive realisation. And, lo and behold, an entire youtube playlist, comprising hours of lectures, on just this topic -The Blind Spot: Experience, Science, and the Search for “Truth” - a workshop with philosophers, physicists, and cognitive scientists (which having discovered, I will now review, but I believe it is linked to this Aeon article from a few years back.) -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesNot at all but the distinction shouldn’t be lost sight of

-

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesGive us an example from psychophysics or cognitive neuroscience. — apokrisis

Ahem. Sign on the door says “philosophy forum’. And arguably the reason for the repeated failures to find a theory is a philosophical one. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesMight be murky, but it's still a line.

-

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesWhat first counts as a living organism? — apokrisis

That’s pretty clear from extrapolating the fossil record isn’t it? Stromatolites or something like it? In any case whatever it was had to maintain itself, grow, heal, mutate and evolve. Minerals don't do that, but organisms do. That much is clear, isn't it? -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesfor some reason, reminds me of the arguments about superposition in physics.

-

Enthalpy vs. EntropyWayfarer said “gesture towards non-being”. — schopenhauer1

I said that for modern anti-natalism, as distinct from gnosticism 'Existence is a mirage, a trap, a painful charade, but there’s nothing higher to aspire to. Only the wan idea that maybe if we don’t procreate, then we’ve made a meaningful gesture towards non-being'. The difference being that in gnosticism there is still the understanding of salvation from suffering or release into a higher realm, albeit perilously hard to attain.

There's absolutely zero point in wringing your hands about the fact that you exist. You can wish all you want that you didn't exist, but that horse has, so to speak, already bolted. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesGalileo is hardly to blame for any of this. — wonderer1

It's not like some personal shortcoming but a number of factors that were crystallised in his work, chief among them the division of the world into primary and secondary qualities. According to Galileo's philosophy, primary attributes are intrinsic properties of an object that exist independently of any observer. They are considered objective and measurable. Examples include mass, size, and shape. These attributes are inherent to an object and do not depend on the observer's perception or point of view.

On the other hand, secondary attributes are considered subjective and dependent on the observer. They are not considered to be intrinsic properties of an object but are rather the result of an interaction between the object and the observer's senses. Examples of secondary attributes include color, taste, and temperature. These attributes are perceived by the senses and can vary from one observer to another.

Galileo argued that primary attributes, being objective and measurable, could be studied and understood through mathematical and quantitative analysis. Secondary attributes, being subjective and variable, were not suitable for precise scientific investigation in the same way as primary attributes.

This was to be combined with Descartes' dualism of matter (res extensia) and mind (res cogitans) to give rise to the modern synthesis. Thomas Nagel describes it like this:

The modern mind-body problem arose out of the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, as a direct result of the concept of objective physical reality that drove that revolution. Galileo and Descartes made the crucial conceptual division by proposing that physical science should provide a mathematically precise quantitative description of an external reality extended in space and time, a description limited to spatiotemporal primary qualities such as shape, size, and motion, and to laws governing the relations among them. Subjective appearances, on the other hand -- how this physical world appears to human perception -- were assigned to the mind, and the secondary qualities like color, sound, and smell were to be analyzed relationally, in terms of the power of physical things, acting on the senses, to produce those appearances in the minds of observers. It was essential to leave out or subtract subjective appearances and the human mind -- as well as human intentions and purposes -- from the physical world in order to permit this powerful but austere spatiotemporal conception of objective physical reality to develop. — Mind and Cosmos pp. 35-36

That's the setting against which David Chalmer's poses the hard problem of consciousness, and when spelled out that way, it's not hard to grasp his rationale. The whole issue of the mind-independence of particular qualities has in any case been undermined by the observer problem.

(Philip Goff seeks to solve the problem by saying that matter is actually conscious in some way, thereby dissolving the duality, but I don't think it works, for reasons I explained in an earlier thread, which Philip Goff himself actually joined the Forum to respond to. Oh, and I don't regard his rebuttal of my criticism successful.)

how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. — Tom Storm

I read a clarification of this trope somewhere. The original dispute was whether two incorporeal intellects (i.e. angels) can occupy the same location in space and time. I don't recall the details but when the background is understood it sounds a little less daft. -

The Argument from ReasonIf we assume that physical systems, as described per physicalism, can indeed produce first person experience... — Count Timothy von Icarus

But we cannot so assume.

Tropes and universals can be described in mathematical, computable terms. — Count Timothy von Icarus

By rational agents - human beings - augmented with intentionally-designed artefacts - computers and calculators. Were those rational abilities absent, there would be no apprehension of tropes or universals. I know it's already been suggested that crows can count, but try explaining the concept of prime to them.

I find it sort of funny in a way, because for the Stoics and many early Christians the fact that the world did move in such a law-like way was itself evidence of the divine Logos, not an argument against the divine. — Count Timothy von Icarus

That is a subject in history of ideas (associated with Arthur Lovejoy's book The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea, published 1936.) One of the major historical themes explored is 'man's changing vision of the cosmos' - from the demiurgos of Plato, to the biblical creation myths, to the mechanical universe of the early modern period, where God became a ghost in his own machine. The concept of natural laws was originally identified with ideas emanating from the One, then as divine commandments, and then as physical laws absent any intentionality or design - which is the view expressed by Russell in that essay. It is that kind of materialism which is challenged by the argument from reason. -

The Argument from ReasonIn most versions of physicalism, which tend to embrace the computational theory of mind (still seemingly the most popular theory in cognitive science), a belief is just an encoding of the state of the external environment. — Count Timothy von Icarus

All very well, but this seems to me to be overlooking or taking for granted a great deal of what is required by such an encoding. I can see how it is perfectly applicable when it come to animals responding to stimuli, but reason is able to do a great deal more than that. It generalises and abstracts, from the particular to the universal. Sure, if you treat life as a kind of model or a game, this approach makes sense - 'Sim Life'. But is it philosophy?

This view works regardless of how consciousness arises, or even if it is eliminated, because agents are not defined in terms of possessing first person perspective, but rather through having goals. — Count Timothy von Icarus

That's what makes it reductionist. You can set aside the first person perspective, and with it, the reality of existence, by treating it as a model, or a board game, as if you were surveying the whole panorama from outside it - when you're actually not.

Lewis seems to conflate the proposition that "the universe and causal forces are meaningless," as in, "devoid of moral or ethical value and describing nothing outside themselves," with agent's beliefs necessarily also being "meaningless," as in "the beliefs must not actually be in reference to anything else." — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think his argument is situated with reference to the classical atheistic materialism of the culture of his day. Have you ever encountered Bertrand Russell's A Free Man's Worship? Published around the turn of the 20th century, it was an anthemic essay dedicated to the purportedly brave and clear-eyed scientific vision of a Universe driven wholly by the forces of physics and man as 'accidental collocation of atoms'. Jacques Monod's Chance and Necessity was another landmark work in similar vein. That vision is also the subject of enormous commentary in 20th century literature, art, drama and philosophy. But I think that hard-edged mentality is already on the wane, 21st century science is more engaged with questions of meaning, acknowledgements of the human aspect of all the sciences and a renewed sense of mystery. The hard edged kind of atheistic materialism that his argument was aimed at will always have its advocates, but there's an abundance of alternatives today (I am enjoying Adam Frank's articles, he's a physics scholar and popular science commentator, see his Science Claims a God's Eye View and his current 'mission statement'.)

'In Aristotle, nous is the specific faculty that enables human beings to reason. For Aristotle, this was distinct from the processing of sensory perception, including the use of imagination and memory, which other animals can do. For Aristotle, nous is what enables the human mind to set definitions in a consistent and communicable way, and provides the innate potential for different persons to understand those universal categories in the same logical ways (and note that Kant adopted Aristotle's categories almost unchanged)..... In this type of philosophy, later considerably elaborated by neoplatonism, it came to be argued that the human understanding (nous) somehow stems from this cosmic nous, which is however not just a recipient of order, but also a creator of it.'

Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and steadily we reflect upon them: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me. I do not seek or conjecture either of them as if they were veiled obscurities or extravagances beyond the horizon of my vision; I see them before me and connect them immediately with the consciousness of my existence. — Immanuel Kant -

How Does Language Map onto the World?There's a well-worn anecdote in linguistics about Eskimos having 39 different words for snow. I seem to recall reading that it's been disputed, but the point of the story is that, due to their environment, Eskimos had many more ways of differentiating the qualities of snow and ice than English does. This was said to be a result of, and have bearing on, many aspects of their day-to-day lives, applicable to hunting activities and many other facets of Eskimo life. (Now I look, there's a rather good Wikipedia entry on the topic.) The point being to illustrate the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis of linguistic relativity, that languages both reflect and influence our perception of the world.

I noticed that some of the innate characteristics of English carry philosophical or perhaps meta-linguistic implications which are barely noticed by speakers, as it's woven into their way of speaking.

One example arises from the propositional structure of the language which differs from the inflected languages like Latin, where the declensions of verbs are given in the verb suffix rather than distinct particles 'I', 'we', 'they' etc. The effect of this is seen, for example, in the expression 'it is raining', which suggest 'an object which rains'. (This is something I remember Alan Watts commenting on.) What is the 'it' that rains? Really there is no such object, there is simply 'raining' but the structure of our language is such that it has to be expressed in those terms. This underlying structure tends to make English a rather transactional language, comprising objects, subjects and activities, which reflects a somewhat 'atomised' conception of reality, rather than imparting a sense of flow or union which is suggested in other languages.

In a more general sense, I often reflect on the paucity of current English for dealing with what I consider some essential philosophical ideas and distinctions, particularly in the area of metaphysics and philosophy of religion. Indeed, both those are nowadays 'boo words' which carry a lot of historical baggage and provoke the associated responses. Another such word is 'spiritual', which is used in a very broad sense to denote a kind of non-specific religious sensibility. But I know from Buddhist studies that there's actually no word corresponding to 'spiritual' in Buddhism, and likewise that many of the key words in the Buddhist lexicon (dharma, dukkha, saṃsāra, vijnana, many others) have no single-word equivalent in English. Instead they are mapped against what are thought to be their equivalents, often derived from the Christian lexicon, against which they're really not a good fit.

The way I have come to understand it is that there are domains of discourse within which words derive their meaning. I don't know if there is anything like a universal language in that sense (although maths and physics would come close, but they're not languages in the sense being discussed.) Hence the significance of hermeneutics, which is mainly aimed at understanding language within its particular domain of discourse. -

The Argument from ReasonIn effect, small infants live in a different world from us, with different or perhaps only fewer laws of thought. They transition to ours, mostly. — Srap Tasmaner

And generally learn to speak as a part of that. Something which is also unique to h. sapiens.

Object identity is not an identical property to that of what the law of identity stipulates. — javra

The law of identity itself originates with Greek philosophy with Parmenides assertion that "what is, is," and "what is not, is not", suggesting that something is what it is and cannot be what it is not. Later, in the Phaedo, there is the 'argument from equals' where Socrates argues that, in order to ascertain that two objects have the same length, we must already have the 'idea of equals' in order to make the judgement as to sameness and difference.

My belief is that our every rational act is suffused with such judgements of sameness and difference, is/is not, equals/unequal. And because it structures our cognition, these are also inherent in reality as experienced by us.

So again, our big metaphysical question is what is the fundamental model of the causality/logic of the Universe? — apokrisis

The lesson of philosophy since Kant is that we can't see the Universe from some point outside our own cognitive apparatus - that the world and the subject are inextricably intertwined. The world and the self have distinctive existences within that matrix but the world remains an experience-of-the-world. Within that matrix logic and mathematics are formal structures which are replicable and inter-subjectively verifiable, but I say it's a mistake to think of them as being 'in the mind'. They're neither 'in here' nor 'out there' but structures within the experience-of-the-world. Reason provides the means to abstract, predict, and generalise, which is why Greek philosophy held reason in such esteem as it provided insight into thecausalformal domain, whereas sensory consciousness only reveals the phenomenal domain. -

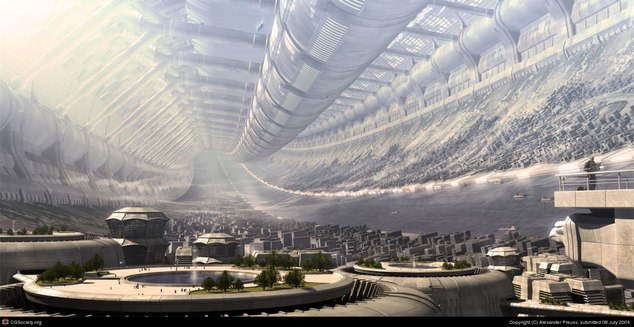

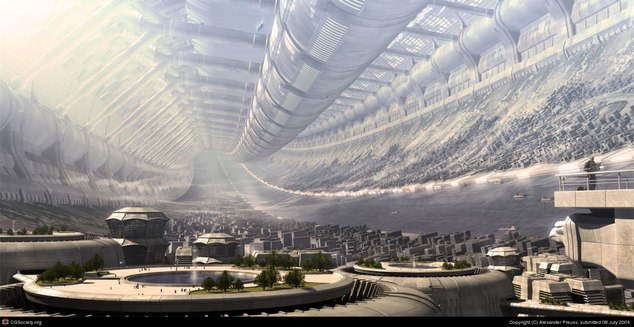

Avi Loeb Claims to have found evidence of alien technologySometimes it's hard to put things just right. It came from outer space, right; but where we are is ALL outer space. — BC

Sorry, not 'extraterrestrial' but interstellar. That was the term I got wrong. The significance being that almost every meteor or space object known originates from inside the solar system (usually the Asteroid Belt.) 'Oumaumau was thought to be of interstellar origin because of the orbit - it looped around the Sun and then took off again out of the solar system. Remember Rendevouz with Rama? One of my all time favourite sci-fi stories. (Nothing to do with this graphic but I've always just liked it.)

-

Avi Loeb Claims to have found evidence of alien technologyIt is saying nothing surprising that this object speeding across the solar system and then heading back out is "extraterrestrial". How could it be otherwise? — BC

Sorry my bad. From ‘outside the solar system’, I meant. Different class of object. -

Enthalpy vs. EntropyBuddhists do it when they say that humans need to be born to suffer to escape suffering. — schopenhauer1

Yeah, it wouldn't make any sense if there were no real good. -

Enthalpy vs. EntropyEntropy is a measure useable information — apokrisis

That differs from the dictionary definition.

Incidentally there's a well-known anecdote concerning a conversation that occurred in in around 1940-41 in a discussion between Claude Shannon and John Neumann, during Shannon’s postdoctoral research fellowship year at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, New Jersey, where Neumann was one of the main faculty members. During this period Shannon was wavering on whether or not to call his new logarithmic statistical formulation of data in signal transmission by the name of ‘information’ or ‘uncertainty’ (of the Heisenberg type). Neumann suggested that Shannon use neither names, but rather use the name ‘entropy’ because: (a) the statistical mechanics version of the entropy equations have the same mathematical isomorphism and (b) nobody really knows what entropy really is so Shannon would have the advantage in any argument.

This is sometimes dismissed as an urban myth but I believe that there is documentary evidence of Shannon himself attesting to it. I like the fact that rhetorical considerations come into it. -

The Argument from ReasonThat implies intent to deceive or mislead, which I assure you was not present. — Srap Tasmaner

Not accusing you of that at all. Overall your criticism has been relevant...well, up until the excursion into marine biology. It's the zeitgeist, the spirit of the times. A related topic I often explore is the vexed question of mathematical platonism - whether numbers are discovered or invented. The connection between the two questions ought to be pretty clear. The point being that the heavy-hitters in philosophy of maths all decry any form of platonism, on the grounds that it verges on a spooky ability to grasp non-physical truths.

How do you know that some truths are necessary? How do you know that logic is not "something of our own manufacture"? — Janus

The child can always endlessly ask 'why?' — Janus -

Avi Loeb Claims to have found evidence of alien technologyI've been sporadically following Avi Loeb, even before all of this blew up, because he's an interesting scientist. (I've written him into my not-yet-finished sci fi novel under another name.) His Harvard homepage can be found here, and his Medium articles index here. What I noticed about his 'Ouamuamua coverage, which included a book, was his dogmatic insistence that this object must be an extraterrestrial artifact. That is what other scientists have taken him to task for. He seems to brook no disagreement, and has written polemical articles attacking critics for being narrow-minded and dogmatic.

Let's see. Of course, if he's correct, then it will be one of the greatest ever scientific discoveries. -

The Argument from ReasonWayfarer's OP seem to be falsely accusing him of making unsubstantiated scientific (physical) assertions, while ignoring his explicit framing of the topic in terms of philosophical (metaphysical) concepts. He was not arguing against Evolution or Biology, but against the axiomatic (unprovable) metaphysical beliefs of Materialism — Gnomon

:100:

I think we think the way we do, and find success thinking the way we do, because nature is the way it is. We do think of logic as being above natural law, as being prior to it, but in a universe that behaved very differently than this one, if there could even be creatures like us to speculate, insisting upon the logic that works in this universe would look foolish, and nothing like the high road to truth. — Srap Tasmaner

Notice this rhetorical sleight-of-hand which re-frames necessary truths as contingent. This is often deployed by way of speculations about the ‘multiverse’. It relativises the issue by suggesting that logic is 'for us', again, something of our own manufacture. Even what were customarily considered necessary truths are only conventions, after all. To be so bold as to suggest the origins of 'natural law' in Neoplatonism would be 'metaphysical speculation' but to casually introduce the possibility of 'other universes' barely causes a ripple. Even though it is:

a relativism that, again, is thereby devoid of any impartial, existentially fixed standards (in the form of principles or laws) by which all variants of logic/reasoning manifest. — javra

Peirce has a trifold system to this effect and - something that apo so far has disallowed in my conversations with him - the principle of Agapism as ultimate cosmic goal. — javra

I’ve noticed that Apokrisis tends to acknowledge only those aspects of Peirce’s philosophy which are pragmatically useful for modelling semiotic relationships whilst often disavowing his broader idealism. As Thomas Nagel put it, 'Even without God, the idea of a natural sympathy between the deepest truths of nature and the deepest layers of the human mind, which can be exploited to allow gradual development of a truer and truer conception of reality, makes us more at home in the universe than is secularly comfortable'. I think that discomfort is often on display in these kinds of discussions. -

Addiction & Consumer Choice under NeoliberalismWell, some of the counter cultural sources you mentioned are examples. E F Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful was one, and there is still a foundation with his name on it. One of my oldest friends has just bought into the Narara Eco-village, which has been made along those lines. (Did you ever encounter Theodore Roszak’s books, particularly Making of a Counter-Culture and Where the Wasteland Ends? Don’t know how they would hold up now, but they a made a big impression on me at the time.) So I agree, I think that counter-cultural meme was a step in that direction, but it kind of fizzled, or became incorporated (although it’s still had huge consequences - Steve Jobs arguably being one.)

But it needs something much more profound than a counter-cultural movement, although maybe I’m speaking out what I myself most need to do :halo: -

Addiction & Consumer Choice under NeoliberalismYes I am going to have to do likewise. But what I was getting at was more philosophical and political. I mean, liberal market economics are based around economic growth and consumption. Whilst it might be virtuous and practical to pursue minimalism and a frugal lifestyle, there’s nothing much in the public sphere that encourages it, and there’s no philosophical rationale for it on the cultural level.

Consider the Kumbh Mela festival in India. It celebrates renunciation and draws literally millions (I think I read the last was the largest assembly of humans in history, but then, there’s no shortage of people in India.) But the point here is that in Indian culture, renunciation is recognised as a virtue and not just on a personal or individual level. May not be a very practical example, but it represents a very different kind of social philosophy. -

How Does Language Map onto the World?There are instances of people without language that are able to form thoughts, plan ahead and act out. — I like sushi

How would you know? Any examples you could mention? Do you mean, deaf-mute people? -

Addiction & Consumer Choice under NeoliberalismSurely, consumerism is a large part of Western culture but how can there be no philosophical or social frameworks outside of it? — Judaka

Got any examples in mind? Any particular cultural forms you can point to? -

How Does Language Map onto the World?Ever run across the Saphir-Whorf hypothesis? Also known as linguistic relativity, it proposes that the language we speak influences the way we think and perceive the world around us. It suggests that language shapes our thoughts, cognition, and even our cultural worldview. The hypothesis is named after the linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf, who developed these ideas in the early 20th century.

There are two versions: the strong (linguistic determinism) and the weak version (linguistic relativity).

The strong version posits that language determines thought entirely and that we can only perceive and understand things that we have words for in our language. In other words, without specific words or linguistic structures for certain concepts, those concepts cannot be fully grasped or expressed by speakers of that language.

The weak version more modestly suggests that language influences thought and cognition but doesn't entirely determine it. It acknowledges that language plays a significant role in shaping our perceptions and understanding of the world, but also recognizes the influence of other factors such as culture, social context, and individual experiences. More here. -

The Argument from ReasonDid you know that humpback whales -- I think I'm remembering this right -- fuck with orcas? — Srap Tasmaner

Gee, I must have missed that. I'd better go back and read the Argument from Reason again. -

The Argument from ReasonWhere does the transcending biology come in? Is being a living thing not extraordinary enough? — Srap Tasmaner

I feel there's a distinction here that you're not seeing. But then, that's been the case all through this thread. Thanks all the same for your responses. -

The Argument from ReasonAnother relevant snippet from Horkheimer:

:lol: :lol: :lol:We might say that the history of reason or enlightenment from its beginnings in Greece down to the present has led to a state of affairs in which even the word 'reason' is suspected of connoting some mythological entity. -

The Argument from ReasonWhy do we alone transcend biology? — Srap Tasmaner

Aristotle differentiated man as ‘the rational animal’. Rationality is certainly one aspect - it enables h sapiens to see well beyond the stimulus-response perception of other creatures. There are other faculties as well, artistic, spiritual, philosophical, scientific - I think these differentiate h. Sapiens from other creatures. You don’t agree? -

Addiction & Consumer Choice under NeoliberalismTo what extent should consumers be free to make choices about what products and services they consume in the context of neoliberal capitalism? — Judaka

They should be free to make those choices, but it is an unfortunate fact that consumers are heavily exploited for commercial gain.

The problem is a philosophical one. There is no countervailing ideology to consumerism, because there's no philosophical or social framework that recognises anything other than consumption and material goods. There have been many such cultures and probably still are in some pockets of society, but the overwhelming ethos of consumer capitalism is - well - consumption. And it's going to take a lot more than political persuasion or good intentions to change that. Perhaps something like having to adapt to global shortages and wide-scale resource depletion. 'The beasts', saith Heraclitus, 'are driven to the pasture by blows'. -

The Argument from ReasonWe like to think we have a certain destiny, but that is radically mistaken, human hubris. — Janus

also a convenient way to dodge the implications of our existential situation. -

The Argument from ReasonI can't help feel that it is animals who often live the superior life... — Tom Storm

Perhaps that innocence is what was lost in the mythology of the Fall.

Both seemed to assume, more or less as I do, that our intelligence is on some kind of continuum with other animals. "Continuum" is not a great word there, though, because it may not be a matter of having more or having less of one thing, general intelligence, but of having more or having fewer cognitive skills, particular abilities. — Srap Tasmaner

The problem-solving abilities of crows and such are often cited in this context. Parrots are also clearly intelligent with problem-solving skills. I suppose it's seen as the basis for a continuum, a proto-version of what our intelligence turns out to be, so conforming with the idea of 'gradual development'.

But I see a radical break - an ontological distinction, in philosophical terms - at the point where humans become fully self-aware, language-using and rational creatures.

I think the cultural dynamics behind this, is that for modern culture, 'nature' is now the nearest thing we have to 'the sacred'. Hence the (laudable) reverence for environment, first nations peoples, and so on. Conversely Biblical religions are said to have encouraged the subjugation of nature. So the assertion of a radical difference between humans and animals is, I think, seen as a relic of Judeo-Christian mythology.

There's a passage in Max Horkheimer's book, The Eclipse of Reason, about this dynamic:

In traditional theology and metaphysics, the natural was largely conceived as the evil, and the spiritual or supernatural as the good. In popular Darwinism, the good is the well-adapted, and the value of that to which the organism adapts itself is unquestioned or is measured only in terms of further adaptation. However, being well adapted to one’s surroundings is tantamount to being capable of coping successfully with them, of mastering the forces that beset one. Thus the theoretical denial of the spirit’s antagonism to nature – even as implied in the doctrine of interrelation between the various forms of organic life, including man – frequently amounts in practice to subscribing to the principle of man’s continuous and thoroughgoing domination of nature. Regarding reason as a natural organ does not divest it of the trend to domination or invest it with greater potentialities for reconciliation. On the contrary, the abdication of the spirit in popular Darwinism entails the rejection of any elements of the mind that transcend the function of adaptation and consequently are not instruments of self-preservation. Reason disavows its own primacy and professes to be a mere servant of natural selection. On the surface, this new empirical reason seems more humble toward nature than the reason of the metaphysical tradition. Actually, however, it is arrogant, practical mind riding roughshod over the ‘useless spiritual,’ and dismissing any view of nature in which the latter is taken to be more than a stimulus to human activity. The effects of this view are not confined to modern philosophy. — Eclipse of Reason, pp. 123-127

(Important to note that Horkheimer is referring to 'popular Darwinism' which he distinguishes from what Darwin himself wrote.)

Language, for example, allows displacement, the ability to communicate about objects not in our present surroundings; you could describe that as "transcending" the limit of referring only to what other animals can or do perceive. — Srap Tasmaner

That's certainly part of it. There's a book I've never got around to (one of thousand) by Chomsky and a collaborator, Why Only Us? In that book Chomsky and Berwick argue that human language is a distinct and innate cognitive capacity that sets us apart from other animals. They propose that language is not a result of gradual evolution, as commonly believed, but rather a sudden and unique emergence in human history. They emphasize that the development of language cannot be explained by natural selection acting on incremental changes, as is the case with other biological traits. (Chomsky however always intends to stay within the confines of naturalism, whereas I myself don't suffer from that inhibition.)

In any case, in traditional philosophy and religion, I believe the reverence accorded to reason as a kind of 'divine instrument' is at least symbolically meaningful. After all, here we are, the day before yesterday we were chasing wildebeest around the savanah, now we're able to weigh and measure the Universe. Something which no crow will ever do.

If you're saying that here's something that by definition evolution can't do, then you're playing semantic games and the rest of us can ignore you. — Srap Tasmaner

Again - it's not evolutionary theory that is at issue, but darwinian materialism, represented in popular culture by Dawkins and Dennett, but implicit in a great deal of naturalism. Not all though. There are non-materialist evolutionary biologists, many of those mentioned by Apokrisis, for instance Robert Rosen:

For centuries, it was believed that the only scientific approach to the question "What is life?" must proceed from the Cartesian metaphor (organism as machine). Classical approaches in science, which also borrow heavily from Newtonian mechanics, are based on a process called "reductionism." The thinking was that we can better learn about an intricate, complicated system (like an organism) if we take it apart, study the components, and then reconstruct the system-thereby gaining an understanding of the whole.

However, Rosen argues that reductionism does not work in biology and ignores the complexity of organisms. Life Itself, a landmark work, represents the scientific and intellectual journey that led Rosen to question reductionism and develop new scientific approaches to understanding the nature of life. Ultimately, Rosen proposes an answer to the original question about the causal basis of life in organisms. He asserts that renouncing the mechanistic and reductionistic paradigm does not mean abandoning science. Instead, Rosen offers an alternate paradigm for science that takes into account the relational impacts of organization in natural systems and is based on organized matter rather than on particulate matter alone. — Life Itself

Are you in the trenches of biology, offering an alternative theory? — Srap Tasmaner

I’m not ‘in the trenches’, but there's a lot of dissent from the neo-darwinian orthodoxy.

The vast majority of people believe that there are only two alternative ways to explain the origins of biological diversity. One way is Creationism that depends upon intervention by a divine Creator. That is clearly unscientific because it brings an arbitrary supernatural force into the evolution process. The commonly accepted alternative is Neo-Darwinism, which is clearly naturalistic science but ignores much contemporary molecular evidence and invokes a set of unsupported assumptions about the accidental nature of hereditary variation. Neo-Darwinism ignores important rapid evolutionary processes such as symbiogenesis, horizontal DNA transfer, action of mobile DNA and epigenetic modifications. Moreover, some Neo-Darwinists have elevated Natural Selection into a unique creative force that solves all the difficult evolutionary problems without a real empirical basis. Many scientists today see the need for a deeper and more complete exploration of all aspects of the evolutionary process. — The Third Way of Evolution

Steve Talbott whom I mentioned previously is represented on this site, along with many others, none of them ID representatives (which is the inevitable suggestion for anyone who questions the consensus.) -

The Argument from ReasonAnother way to read what I actually wrote was from the general to the specific, just taxonomy spread out chronologically, something speciation tends to do. — Srap Tasmaner

Your use of the word 'finally' clearly suggests goal-directedness.

I have said numerous times in this thread that h. sapiens has plainly evolved in the sense described by the theory of evoluition. But that with the development of language and reason, we transcend purely biological determination in a way that other animals do not. Only humans can consider questions such as whether there are domains of being beyond the sensory world, for example, not to mention more quotidian abilities, such a mathematics, science, and so on. -

The Argument from Reasont threw up mammals, then simians, then hominids, then finally something like us. — Srap Tasmaner

I think you will find that any idea of there being progress in this sense is rejected by mainstream biology on account of it being orthogenetic which is defined as the theory that evolutionary variations follow a particular direction and are not sporadic and fortuitous. As it happens the process has turned out h. sapiens, but there's no reason given in the theory as to why that particular outcome. And indeed the fact that there is no reason in that sense is central to the whole argument.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum