Comments

-

The Argument from ReasonConcepts and numbers exist for us in a different way than concrete objects, and so on. — Janus

:lol: There is huge controversy over their reality and whether number is invented or discovered and so on. Empiricist philosophers like yourself generally reject the notion that they have any reality apart from as the product of the mind (read 'brain'.)

Platonism, as mathematician Brian Davies has put it, “has more in common with mystical religions than it does with modern science.” The fear is that if mathematicians give Plato an inch, he’ll take a mile. If the truth of mathematical statements can be confirmed just by thinking about them, then why not ethical problems, or even religious questions? Why bother with empiricism at all?

Massimo Pigliucci, a philosopher at the City University of New York, was initially attracted to Platonism—but has since come to see it as problematic. If something doesn’t have a physical existence, he asks, then what kind of existence could it possibly have? “If one ‘goes Platonic’ with math,” writes Pigliucci, empiricism “goes out the window.” (If the proof of the Pythagorean theorem exists outside of space and time, why not the “golden rule,” or even the divinity of Jesus Christ?) — What is Math?

Why not indeed? (My bolds, and also my point.)

In the Catholic world it is just the opposite! That thesis is so prevalent that it is thought to be trite. — Leontiskos

Which I suspect is the reason for its unpopularity outside that world. Incidentally you'll find a breakdown of Anscombe's criticism of Lewis' argument in Victor Reppert's essay (Reppert authored a book on the argument.)

That line says that the nominalism that was conceived with Duns Scotus and came to maturity with William of Ockham is the crucial error that fueled the loss of realism and set the stage for the modern period. I think there's a lot of truth to it, although there is nuance to be had. — Leontiskos

The role of Duns Scotus and the eclipse of scholastic realism is also central to John Milbank's 'Radical Orthodoxy' as I understand it (see this blog post). -

The Argument from ReasonFrom the OP (based on the C S Lewis form of the argument):

The argument from reason challenges the proposition that everything that exists, and in particular thought and reason, can be explained solely in terms of natural or physical processes. It is, therefore, an argument against materialist philosophy of mind. — Wayfarer

And quoted above, from Gerson's paper

The antimaterialist maintains that there are entities that exist that are not bodies and that exist independently of bodies — Lloyd P. Gerson, Platonism Versus Materialism | cf. From Plato to Platonism, 11

The convergence of the two quotations ought to be clear - which is hardly surprising, since Lewis, as a Christian intellectual, no doubt defends a broadly Platonist point of view, considering the incorporation of many elements of Platonism into Christianity.

As we've now re-introduced Gerson, I'll provide a bit more detail from the essay quoted above:

(Gerson defends the) thesis that most of the history of philosophy, especially since the 17th century can be characterized as failed attempts by various Platonists to seek some rapprochement with naturalism and, mostly in the latter half of the 20th century and also now, similarly failed attempts by naturalists to incorporate into their worldviews some element or another of Platonism. I would like to show that what I am calling the elements of Platonism...are interconnected such that it is not possible to embrace one or another of these without embracing them all. In other words, Platonism (or philosophy) and naturalism are contradictory positions. — Lloyd Gerson, Platonism vs Naturalism

The elements of ‘Ur-platonism’, according to Gerson’s hypothesis are: anti-materialism, anti-mechanism, anti-nominalism, anti-relativism, and anti-scepticism, summarised below

Anti-materialism rejects the notion that only bodies and their properties exist. It allows for entities beyond bodies, like souls. Anti-mechanism states that materialist explanations are inadequate and proposes non-bodily explanations for material phenomena. Anti-nominalism denies that only individuals exist and allows for sameness in difference (i.e. the role assigned to forms or universals). Anti-relativism opposes the view that truth and goodness are subjective and emphasizes their objective or transcendental determinations. Anti-scepticism asserts that knowledge is possible, countering scepticism's doubt about attainable knowledge. (Refer to reference above for detailed content).

What is at issue is how to understand properties. — Paine

It is in this respect where I proposed the revisionist understanding of the nature of intelligibles (such as forms, numbers, the soul, and so forth.) This is not of my devising, as it is elaborated in an historical source, namely the writings of theological philosopher Scotus Eriugena (as I'll explain). The gist of this argument is that 'the soul' does not exist in the sense that the terms 'entity' and 'exist' are understood within the framework of naturalism. As an illustrative example, numbers and other intelligibles, such as 'the concept of prime', likewise do not exist in the sense that chairs, tables, and the objects of natural science exist. Their existence is purely intelligible, i.e. only perceptible to a rational mind. They are nevertheless real, in that they have the same value for all who can grasp them. As Bertrand Russell says in The World of Universals, 'universals are not thoughts, though when known they are the objects of thoughts.' The rational soul (psyche) is what can perceive these ideas but itself is not a cognizable entity. So to make of the soul an entity, as the body is an entity, is an (understandable) error of reification (literally, 'to make a thing out of').

This is from the SEP entry on Scotus Eriugena. (I have taken the liberty of replacing 'to be' with 'to exist' to draw out the point I'm trying to articulate):

Eriugena lists “five ways of interpreting” the manner in which things may be said to exist or not to exist. According to the first mode, things accessible to the senses and the intellect are said to exist, whereas anything which, “through the excellence of its nature”, transcends our faculties are said not to exist. According to this classification, God, because of his transcendence is said not to exist. He is “nothingness through excellence” (nihil per excellentiam). (On this, also see Whalon, God does not Exist).

The second mode of existence and non-existence is seen in the “orders and differences of created natures” whereby, if one level of nature is said to exist, those orders above or below it, are said not to exist:

For an affirmation concerning the lower (order) is a negation concerning the higher, and so too a negation concerning the lower (order) is an affirmation concerning the higher. (Periphyseon, I.444a)

...This mode illustrates Eriugena’s original way of dissolving the traditional Neoplatonic hierarchy of being into a dialectic of affirmation and negation: to assert one level is to deny the others. In other words, a particular level may be affirmed to be real by those on a lower or on the same level, but the one above it is thought not to be real in the same way. — John Scotus Eriugena, Dermot Moran, SEP

This is obviously a rather recondite set of distinctions, but to me it is the only way to make sense of the reality of intelligibles, such as universals, number, and the like, because it restores a dimension of reality or being that has been 'flattened out' in the transition to modernity with its exclusive concentration on material and efficient causation. Consequently, there is no conceptual space for the idea that there are different levels or domains of reality - to us, things either exist or do not exist, they do not exist 'in different ways'. -

Aristotelian logic: why do “first principles” not need to be proven?it's still reasonable to say that the brain is hierarchical and that those hierarchies are based on physiology primarily. — Isaac

Nifty segue! -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesI'm sorry, if my equation of Energy & Mind annoys you — Gnomon

It doesn’t annoy me, but I’m not persuaded by it.

I have to repeatedly remind TPF posters that the original meaning of the word "Information", was " knowledge and the ability to know". — Gnomon

Not according to the Oxford Dictionary online edition. It says the first use of the term was in relation to:

accusatory or incriminatory intelligence against a person. Excepting specific legal contexts, that’s no longer an active sense, though it survives as a dominant meaning of related terms like ‘informant’ and ‘informer’. -

The Argument from ReasonHad I been schooled in the Classics I would have a much better knowledge of the texts. Regrettably it was not part of my education, a lack that I have only come to regret much later in life, and one which I don’t think I will ever really overcome. All I have are a few straws to grasp at, grounded on the scattered readings I have done. And also the intuition that many contemporary readings of Plato downplay or redact out those elements which are incompatible with the type of naturalism which prevails in today’s academia. That is in line with what I believe is the forgetting or occlusion of the qualitative dimension of existence which begins to become apparent in Hume - the loss of the ‘vertical axis’.

One of those straws is the belief that the parable of the cave does indeed present an allegory for a kind of intellectual illumination or an insight into a higher domain of being, and that those who have ascended to it see something which others do not, as I think the allegory plainly states. (I’m of the view that this is what is represented by the later term ‘metanoia’ which is not found in the Platonic dialogues but which means in this context an intellectual conversion or the breakthrough into a new way of seeing the world.) I suppose one secondary source I could refer to for support is this SEP entry on ’divine illumination’ in Greek philosophy.

My revisionist interpretation of the basic issue revolves around the question of the reality of universals, numbers, and other such intellectual objects (such as logical laws etc). I have the idea that number (for example) does not exist in the sense that phenomenal objects exist, but it is nonetheless real. Hence this is an important ontological category that this applies to, that is constitutive of rational thought, but which is not phenomenally existent. I think this understanding is kind of implicit in Platonic epistemology with the distinction between different levels of knowledge in the Analogy of the Divided Line. Platonic realism developed into Aristotelian realism, which was maintained up until scholastic realism, after which it was overthrown by nominalism and later by scientific empiricism. (This is the subject of the book I mentioned, The Theological Origins of Modernity.)

About the only contemporary representative of those kinds of views is Edward Feser (and also maybe Gerson who we already discussed.) I’m trying to fill in the very many blanks in this account, but to date I haven’t encountered anything which would cause me to think it’s entirely mistaken. -

The Argument from ReasonOf course not. But there is plenty of scope for different interpretations.

-

The Argument from ReasonTimaeus proposes it is best to accept likely stories and not search for what is beyond the limits of our understanding. — Fooloso4

A theme also found in Kant.

I think I'll try to find a thread on the Forms to see what's been said here. — Tom Storm

Fooloso4's reading of Plato generally deprecates the widespread view that the knowledge of the forms corresponds to insight into a higher realm of truth. Plato's dialogues are open to a variety of interpretations by their very nature, and I don't think I agree with his interpretation. But to disagree would require re-visiting and re-reading many a dusty tome, so I think I'll regard his as one among other possible interpretations. -

The Argument from ReasonThese are all very deep questions. I’m hardly equipped to make a comparison between Platonic philosophy and Asiatic teachings of enlightenment (although one of my books, The Shape of Ancient Thought, Thomas McEvilly, does go into that in detail.)

Bertrand Russell says in his chapter on Pythagoras that the numerological and rationalist tendency in Pythagoras and in the later Greek tradition is one of the things that differentiates it from Asiatic mysticism. Seems to me that the Greek approach was far more likely to give rise to later science than the Indian and Chinese traditions. But it’s also true that since the Renaissance, the West has kept those elements of the tradition which were useful for science and technology while abandoning the ethical and moral precepts of Aristotelian thought (cf Alisdair MacIntyre). That might be because of the absorption of those principles into theology so that they became rejected along with religion.

I firmly believe that Greek philosophy held to the necessity of ‘the philosophical ascent’, but that with the loss of the qualitative dimension, ‘’the great chain of being’, then the idea becomes unintelligible. (Hence the tension between tradition and naturalism.) There is no axis along which the idea of ‘higher’ makes any sense. Everything is said to have arisen from self-organising matter, ideas only exist in the minds of h. Sapiens, chiefly to serve instrumental purposes. The modern world is very much at odds with the philosophical vision of the Greeks in that sense. -

The Argument from ReasonIn a well-known argument Gerson claims that the immateriality of the intellect disproves materialism. — Leontiskos

Just noticed your post now.

I have read some of Lloyd Gerson's work, but I find his corpus pretty unapproachable, as it is directed almost solely at his academic peer group, or so it seems to me. He's written a series of books, including one contentiously called Aristotle and Other Platonists, but they're dense with footnotes and polemical skirmishes with competing interpretations. It's a shame his work is not more approachable, because I think his central thesis - that Platonism basically articulates the central concerns of philosophy proper, and that it can't be reconciled with today's naturalism - is both important and neglected. It would be great if there could be a compendium of his writing edited for a more general audience, although I suppose it would still be only a small general audience. (Rather a good lecture on his Possibility of Philosophy here.)

I've long been interested in various aspects of scholastic and platonic realism, i.e. the view that universals and abstract objects are real. There's precious little interest in and support for such ideas here, or anywhere, really. But I'm of the view that it was the decline of scholastic realism and the ascendancy of nominalism which were key factors in the rise of philosophical and scientific materialism and the much-touted 'decline of the West'. But it's a hard thesis to support, and besides, as I say, has very little interest, it's diametrically at odds with the mainstream approach to philosophy.

Some of the sources I frequently cite in support include Bertrand Russell's chapter on The World of Universals, the transcript of a lecture by Jacques Maritain The Cultural Impact of Empiricism, a book section about Augustine on Intelligible Objects, a book called The Theological Origins of Modernity by Michael Allen Gillespie. And this excerpt from a book on Thomistic philosophy which re-states, I think, the same argument Gerson refers to in respect of the immateriality of nous. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesA note on neurophenomenology (subject of one of the papers that was returned):

RevealNeurophenomenology is an interdisciplinary approach that seeks to bridge the gap between the first-person subjective experience (phenomenology) and third-person scientific understanding (neuroscience). It was first proposed by the French philosopher and cognitive scientist, Francisco Varela, in collaboration with the neuroscientist, Evan Thompson, and the Buddhist scholar, Eleanor Rosch. They introduced the concept in their 1991 book titled "The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience."

The term "neurophenomenology" itself emerged in the early 1990s, but its roots can be traced back to the work of philosopher Edmund Husserl and his development of phenomenology in the early 20th century. Phenomenology is a philosophical approach that focuses on understanding conscious experience as it is subjectively lived, rather than reducing it to objective measurements and explanations.

In "The Embodied Mind," Varela, Thompson, and Rosch argued that subjective experience should be taken into account alongside objective data in neuroscience to form a more complete understanding of the mind. They proposed that the study of consciousness should involve not only objective observations of brain activity but also a careful examination of the subjective experience itself.

By integrating the empirical findings of neuroscience with the introspective and experiential insights of phenomenology, neurophenomenology aims to create a more comprehensive and holistic understanding of the mind and consciousness. This approach has since been further developed and refined by various researchers and philosophers, leading to a growing interest in interdisciplinary studies between neuroscience and philosophy.

This is a talk from Evan Thompson (mentioned above) on some of the aspects of this approach. It is directly relevant to the question of 'facing up to the problem of consciousness' -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesWhat was it you said about being condescending? — wonderer1

I said there was no need for it. From what I can see you haven't really had much to say about the substance of the article being discussed. I have cited the original argument, and responses to that from others including Daniel Dennett, throughout this discussion. I'm not gaslighting anyone.

You can Google "neuroscience first person perspective" and see for yourself. — wonderer1

Indeed there are. Most of them were published subsequent to 2005, from what I can see. David Chalmer's article was published in 1996. I think much of the literature reflects that, as it was an influential article and put the idea on the agenda, so to speak. Chalmers is not a neuroscientist, his subject is the limitations of science in respect of understanding the nature of first-person experience, from the perspective of philosophy of mind. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesDid you read the article that this thread is about? Do you have any idea of what the issue being discussed is?

-

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesI like that analogy. Mostly because it aligns with my own little reductive thesis, that everything in the universe is a form of Energy, — Gnomon

It's not an analogy, it's a proposition. The difficulty with your thesis being that energy does not itself exhibit a 'capacity for experience', it acts without any such capacity, which is specific to consciousness. And to say that consciousness is a product of matter-energy is falling back to philosophical materialism. You're not going to arrive at anything like an explanation for where consciousness fits in the grand scheme by equating it with energy (or information, for that matter.)

I'm not offering any thesis, other than to say that consciousness, so understood, is irreducible, i.e. can't be explained with reference to anything else. (Although I might add that if consciousness is the capacity for experience, human consciousness in addition exhibits the capacity for abstract reason.)

Consciousness Cannot Have Evolved, Bernardo Kastrup. -

Evolutionary Psychology- What are people's views on it?My two bobs is that it's a fascinating and fruitful field of study, alongside (paleo)anthropology, linguistics, and other disciplines. But due to the role of evolutionary biology in current culture, it's easy to read too much into it or draw conclusions from it on dubious grounds. A couple of articles in the popular media talking about that theme:

It Ain't Necessarily So, Antony Gottlieb, The New Yorker

Anything but Human, Richard Polt, NY Times -

Aristotelian logic: why do “first principles” not need to be proven?Beautiful. Co-incidentally I was listening to a youtube lecture whilst working out, which mentions a book called The Paradox of Subjectivity, apparently about this paradox.

-

Kant's Notions of Space and TimeAlso, what precludes one from proposing an exemplary Form/Idea for Pine Trees and another exemplary Form/Idea for Elm Trees, etc.? Can't one argue that an exemplary form exists for any experienced entities that share a common set of characteristics? — charles ferraro

Beats me. My study of Plato's forms is still (and will probably always remain) incomplete. I was just responding to your post above, which I think is dubious, for the reasons given. Although I will add that I think it's very easy to confuse 'form' with 'shape' - the original, 'morphe' doesn't mean exactly that. I think it's something nearer to a principle i.e. 'the principle of tree-ness', that which all trees have in common. But as soon as you start to go down the path of analysing that, difficulties multiply, so I won't press the point (and besides it's only tangentially relevant to the OP). -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesSo what is it about organisms that is so special? What characterises them beyond what the bare physics of matter can tell us? — apokrisis

I thought you had distanced yourself from philosophical materialism. Was I wrong?

Organisms are subjects of experience, which is something more than, or other than, simply objects of scientific analysis. This goes for all organisms but is more significant for self-aware animals and rational sentient beings such as humans. To regard living beings as objects is, I think, inhumane and rather presumptious.

Organisms act for reasons other than the physical, even if they're constrained by physical laws. They act for reasons, not simply as a consequence of prior material or efficient causation. The appearance of organisms signifies the appearance of intentionality, even without attributing intentionality to something mysteriously inherent in nature. Perhaps it could be understood in terms of emergence, but in another sense it is also something novel.

Incidentally, the word "karma" (कर्म) means "action," "deed," or "act." It is derived from the root "kṛ" (कृ), which signifies "to do" or "to act" (ultimately derivative from the word for "hand"). In its original context, karma represents the idea that every action has consequences, although plainly a lot more has been read into it. I nevertheless think it is a sound basis for an ethical philosophy. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesIt is why science has special contempt for “theories that are not even wrong”. — apokrisis

And with it, much of philosophy. This thread has largely been characterised by measured consideration of claims and arguments. Very little by way of 'furious speculation'. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesI'm currently reading a book by mathematical physicist Charles Pinter, subtitled : How the Mind Creates the Features & Structure of All Things, and Why this Insight Transforms Physics. — Gnomon

:clap: I've been singing that book's praises on this forum ever since I read it about a year ago. I emailed the author and got a friendly reply (he's well into his nineties now). All of his other books are mathematics textbooks but his homepage notes his interest in neural modelling. I think it's an important but under-rated book - under-rated because Pinter isn't known as a cognitive scientist or philosopher, so it went under the radar. I think his use of the Gestalt is particularly brilliant, he even shows how very simple organisms like fruitflies can be shown to parse sensory information as gestalts (meaningful wholes. See this ChatGPT summary of convergences between Kant and Gestalt.)

Is substance-dualism making a come back? — RogueAI

One has to be very, very careful about the use of the word 'substance' in philosophy generally and this topic in particular. 'Substance' in normal parlance means 'a material with uniform properties'. In philosophy, 'substance' was originally 'substantia' which was the Latin translation of Aristotle's 'ousia'. And that word is a form of the verb 'to be', i.e. much nearer in meaning to 'being' or 'subject' than what we normally consider 'substance' (see this reference).

Among the pernicious consequences of this ambiguity is Descartes' use of the term 'res cogitans'. 'Res' is actually Latin for 'thing', so 'res cogitans' means literally 'thinking thing'. But we also inherit 'thinking stuff' or 'thinking substance', which is completely different from the idea of 'self-aware subject' (although no specific term may be an exact fit.)

Given all those caveats, I think there's a case to be made for a type of dualism. Perhaps it could be argued that consciousness is 'the capacity for experience' in an allegorical manner to energy as 'the capacity for work'// and that physical matter, in the absence of consciousness, lacks the capacity for experience. So that the emergence of organisms is also the emergence of the capacity for experience, which is absent in the non-organic domain.//

Chalmers and Koch are perpetuating a giant public con. You are falling for it. — apokrisis

Your metaphors and explanations are concerned with neural modelling as a function of survival, not with philosophy of mind per se. You referred to Karl Friston as exemplary - the Vox article points out that 'Stripped of all the math, (Friston) suggests that the behavior of all living systems follows a single principle: To remain alive, they try to minimize the difference between their expectations and incoming sensory input.' That would go for fruit-flies and crocodiles, as well as bats and humans on one level. But it says nothing in particular about the nature or meaning of conscious experience. The reason you dismiss Chalmer's paper is because it means nothing to you, given your interests and emphasis. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesThe point I was addressing was the falsity to your claim that, "I agree with Chalmers, on the grounds that objective physical sciences exclude the first person as a matter of principle." — wonderer1

OK, I should have written 'excludes consideration of the first-person perspective....'

It seems that went over your head, — wonderer1

No need to be condescending.

people use "OP" here in a way that I haven't been able to clearly grasp the referent of. — wonderer1

I use to mean both Original Post and Original Poster. As the OP in this case linked to the Chalmers-Koch wager, I took it to be the central point of the OP.

Chalmers was right on the occasion when the bet was made. — wonderer1

And was still right 25 years later, as it happens.

Can you provide a non-paywalled link? — wonderer1

Facing up to the Problem of Consciousness, David Chalmers.

Perhaps the Consciousness problem is "intractable" for empirical science because subjective experience is seamless & holistic, with no obvious joints for reductive science to carve into smaller chunks of Awareness — Gnomon

I agree. A scientific paper I frequently refer to is The Neural Binding Problem(s) by Jerome S Feldman. 'In its most general form, “The Binding Problem” concerns how items that are encoded by distinct brain circuits can be combined for perception, decision, and action.' Under the heading The Subjective Unity of Perception, the paper discusses 'the mystery of subjective personal experience.'

It references Chalmer's paper directly, saying, 'this is one instance of the famous mind–body problem (Chalmers 1996) concerning the relation of our subjective experience (aka qualia) to neural function. Different visual features (color, size, shape, motion, etc.) are computed by largely distinct neural circuits, but we experience an integrated whole. This is closely related to the problem known as the illusion of a stable visual world (Martinez-Conde et al. 2008).' It says that there is no known neural system that accounts for what we all experience as a stable visual world picture. 'What we do know is that there is no place in the brain where there could be a direct neural encoding of the illusory detailed scene (Kaas and Collins 2003). That is, enough is known about the structure and function of the visual system to rule out any detailed neural representation that embodies the subjective experience. So, this version of the Neural Binding Problem really is a scientific mystery at this time.'

There's a Stanford Encyc. of Phil. article on this issue here https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/consciousness-unity/ -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesYes. Chalmers believes that our present scientific approach to understanding consciousness is limited to explaining function. He believes we need to add experience as an explanandum in its own right. — frank

Thank you.

He believes a scientific theory of consciousness is possible. This would be a third-person account. — frank

Although he does say:

As I see it, the science of consciousness is all about relating third-person data - about brain processes, behavior, environmental interaction, and the like - to first-person data about conscious experience. I take it for granted that there are first-person data. It's a manifest fact about our minds that there is something it is like to be us - that we have subjective experiences - and that these subjective experiences are quite different at different times. Our direct knowledge of subjective experiences stems from our first-person access to them. And subjective experiences are arguably the central data that we want a science of consciousness to explain.

I also take it that the first-person data can't be expressed wholly in terms of third-person data about brain processes and the like. There may be a deep connection between the two - a correlation or even an identity - but if there is, the connection will emerge through a lot of investigation, and can't be stipulated at the beginning of the day. That's to say, no purely third-person description of brain processes and behavior will express precisely the data we want to explain, though they may play a central role in the explanation. So as data, the first-person data are irreducible to third-person data. — David Chalmers, First Person Methods...

You inserted "impossibility" there. That isn't Chalmer's view. — frank

Fair point. Might have gotten carried away.

I've read a little of Colin McGinn and listened to an interview with him recently. He doesn't really grab me. I'm interested in phenomenology and Buddhist philosophy of mind, although it's a digression from this OP. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesMy posts to Wayfarer were meant to be a heads up to look back at the very paper he cited. It does not say that science can not explain experience. If he thinks it does, he should point out which passage he believes says that, and we can bring to light where Wayfarer misunderstood. — frank

This is the paragraph I frequently cite:

The really hard problem of consciousness is the problem of experience. When we think and perceive, there is a whir of information-processing, but there is also a subjective aspect. As Nagel (1974) has put it, there is something it is like to be a conscious organism. This subjective aspect is experience. When we see, for example, we experience visual sensations: the felt quality of redness, the experience of dark and light, the quality of depth in a visual field. Other experiences go along with perception in different modalities: the sound of a clarinet, the smell of mothballs. Then there are bodily sensations, from pains to orgasms; mental images that are conjured up internally; the felt quality of emotion, and the experience of a stream of conscious thought. What unites all of these states is that there is something it is like to be in them. All of them are states of experience. — David Chalmers, Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness

Later, he says:

To explain experience, we need a new approach. The usual explanatory methods of cognitive science and neuroscience do not suffice. These methods have been developed precisely to explain the performance of cognitive functions, and they do a good job of it. But as these methods stand, they are only equipped to explain the performance of functions. When it comes to the hard problem, the standard approach has nothing to say.

That's fairly clear cut, is it not? -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesIf you want something involving philosophical zombies, your question makes no sense. — Isaac

On the other hand, it would be great to have a philosophical zombie sherpa help you climb Everest because it wouldn’t matter if they fell off. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesNamely through the introduction of first person perspectives https://consc.net/papers/firstperson.html

Subject of Dennett’s critical article ‘The Fantasy of First Person Science’, which I’ve already mentioned.

In no way have I misrepresented Chalmers’ position in this thread. -

Kant's Notions of Space and TimeIn Plato's dialogues the Forms or Ideas are not differentiated according to specific species or individual instances. Instead, they represent universal concepts that transcend particular instances or examples.

For example, in the context of the Form 'tree,' it would represent the ideal and perfect essence of what a tree is, encompassing all trees' fundamental characteristics. This Form 'tree' would not be limited to a particular type of tree like a pine tree or elm tree, but it would be the ultimate archetype that all trees in the physical world attempt to imitate or participate in to varying degrees of perfection.

It was Aristotle who later introduced the idea of species and many other refinements and elaborations which were to lay the groundwork for the science of classification (which reached its modern form under Linnaeus in the 16th c) -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesOf course, the subject of neuroscience is the human brain, and humans are subjects, but that it not the point at issue. ‘Facing up to the problem of consciousness’ concerns the difficulty, or even the impossibility, of a providing a scientific account of first-person experience due its subjective nature.

The bet which was the subject of the OP was placed in 1998 between David Chalmers and Kristoff Koch as to whether a neurological account of the nature of experience would be discovered in the next 25 years. From the story:

(The article is here.)At the 26th ASSC conference this past weekend, 25 years after the initial wager, the results were declared: Koch lost. Despite years of scientific effort — a time during which the science of consciousness shifted from the fringe to a mainstream, reputable, even exciting area of study — we still can’t say how or why the experience of consciousness arises.

Do you see the distinction that is being made? Have you read the original Chalmer’s paper? -

Kant's Notions of Space and Time‘ .'...we may be surrounded by objects, but even while cognizing them, reason is the origin of something that is neither reducible to them nor derives from them in any sense. In other words, reason generates a cognition, and a cognition regarding nature is above nature. In a cognition, reason transcends nature in one of two ways: by rising above our natural cognition and making, for example, universal and necessarily claims in theoretical and practical matters not determined by nature, or by assuming an impersonal objective perspective that remains irreducible to the individual “I”.'

The Powers of Pure Reason: Kant and the Idea of Cosmic Philosophy

Alfredo Ferrarin -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesI think the Wittgenstein quote refers to the fact that science cannot solve ethical, aesthetic or spiritual questions. — Janus

Quite so. Can’t you see how that also relates to the ‘problem of consciousness’ that is being discussed? -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesYou don't yet understand the epistemic cut — apokrisis

I understand it perfectly well thank you. Since you first mentioned it, I’ve read up on it. I’m talking about epistemology, not systems science or modeling. The epistemological implications are well known in non-dualism but that is bound to be a digression. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesThe argument between Dennett and Chalmers is just an argument over the reality of qualia — Janus

And that term, ‘qualia’, is only ever encountered in academic literature, precisely about this problem.

Let's say the subject is not real anyway, per Buddhism for example — Janus

So whether we talk about "consciousness" as neurobiological awareness or socially-constructed knowing, it is the same epistemic process in action. Cognition as predictive modelling aimed at creating a self in control of its world. — apokrisis

As I’ve said, I think Chalmer’s expression of ‘what it is like to be…’ is simply a rather awkward way of referring to ‘being’. And as I’ve also said, that is not something which can be framed in scientific terms, because there’s no ‘epistemic cut’ here. We’re never outside of it or apart from it. A Wittgenstein aphorism comes to mind, ‘We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have still not been touched at all.’

Cartesian doesn’t reign for that reason at all. It reigns as the implicit metaphysics of modern science (‘modern’ being the paradigm up until the 1927 Solvay conference.) -

Aristotelian logic: why do “first principles” not need to be proven?Is it okay to resurrect older threads? — Leontiskos

Of course! Especially if you’re going to agree with me ;-) -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesBut physical sciences don't exclude the first person as far as I can tell. — wonderer1

There is the presumption that their findings are observer-independent i.e. replicable by anyone, They’re ‘third person’ in that sense. It’s an implicit assumption. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesI'll bet you two crates of fine wine that in five years time neuroscience won't have found my mojo either. — Isaac

Well that assumes you had some to start with :wink: -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesgreatest mystery of all metaphysics... — apokrisis

Not really. The objective point of view doesn't take the subject into consideration - it is only concerned with what is amenable to quantitative analysis from a third person point of view. Philosophy, generally, has a more expansive scope, concerned with existential questions of meaning and being, which may be of little concern to science. But due to the (some would say) disproportionate degree of respect accorded to science and engineering in today's technological culture, such concerns are often misunderstood, trivialised or rejected. Kudos to David Chalmers for having the insight and persistence to surface the issue.

(Interestingly, I notice that the forthcoming blockbuster, Oppenheimer, is shot in both colour and black and white. Christopher Nolan, director, explained "I wrote the script in the first person, which I'd never done before. I don't know if anyone has ever done that, or if that's a thing people do or not. The film is objective and subjective. I wrote the color scenes from the first person. ..." Nolan goes on to explain that “the color scenes are subjective” and “the black-and-white scenes are objective.”

Apparently there's a difference!) -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesUnanswereable questions, I think, although useful grist for the mill for sci-fi stories. (Did you by any chance see Devs?)

So is the argument that consciousness is off-limits because it's first-person, or that one of the things psychology needs to account for is that it is first-person? — Srap Tasmaner

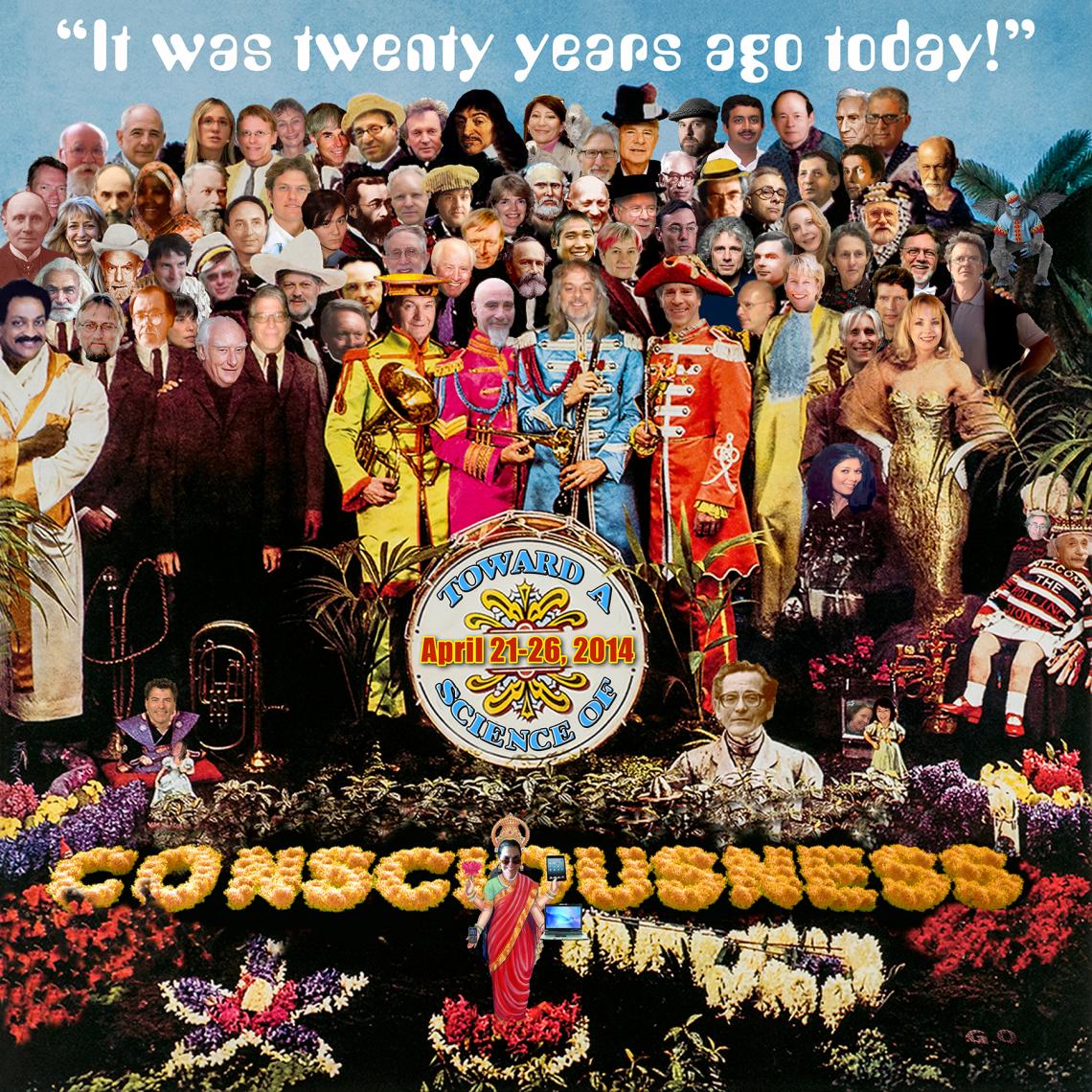

David Chalmer's doesn't say that consciousness is off-limits. He says it is intractable from the third-person perspective, due to its first-person character. He has written extensively on that, e.g. his book 'Conscious Mind: in search of a fundamental theory'. This whole debate between Dennett and Chalmers practically kicked off the modern 'consciousness studies' field, with their conferences in Arizona, featuring a cast of colorful characters and some truly mind-bending ideas.

I think the more interesting approach is the phenomenological/hermeneutic/existential approach in continental philosophy. Also the intersection of phenomenology and Buddhist philosophy of mind in the embodied cognition approach (e.g. The Embodied Mind, Varela Thompson et al.) -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesI think you're aware of this discussion in exactly the same sense that I'm aware of this discussion. — Srap Tasmaner

But that takes for granted that you and I are both subjects of experience, so that you can safely assume that I will understand what you mean. And for the purposes of describing or acounting for objective phenomena, the fact that we're both subjects can be ignored. But in the philosophical question of the nature of consciousness, insofar as that is a first-person experience, it can't be ignored, nor can be accounted for in those terms.

As John Searle put it:

in his book, Consciousness Explained, Dennett denies the existence of consciousness. He continues to use the word, but he means something different by it. For him, it refers only to third-person phenomena, not to the first-person conscious feelings and experiences we all have. For Dennett there is no difference between us humans and complex zombies who lack any inner feelings, because we are all just complex zombies. ...I regard his view as self-refuting because it denies the existence of the data which a theory of consciousness is supposed to explain...Here is the paradox of this exchange: I am a conscious reviewer consciously answering the objections of an author who gives every indication of being consciously and puzzlingly angry. I do this for a readership that I assume is conscious. How then can I take seriously his claim that consciousness does not really exist?

Does ChatGPT have a first person perspective? — RogueAI

No, ChatGPT does not have a first-person perspective. It is an artificial intelligence language model that generates text based on patterns it has learned from a large dataset. It does not possess personal experiences or consciousness. Instead, it provides responses based on the information it has been trained on. Its purpose is to assist users in generating human-like text based on the prompts and questions it receives. — ChatGPT

ChatGPT knows something that Dennett doesn't. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesBut if you define a phenomenon so that its first-person-ness is part of the phenomenon, we're in "Hand me the book on the shelf" territory. — Srap Tasmaner

Right - that is the issue. The key paragraph in David Chalmer's original paper was:

The really hard problem of consciousness is the problem of experience. When we think and perceive, there is a whir of information-processing, but there is also a subjective aspect. As Nagel (1974) has put it, there is something it is like to be a conscious organism. This subjective aspect is experience. When we see, for example, we experience visual sensations: the felt quality of redness, the experience of dark and light, the quality of depth in a visual field. Other experiences go along with perception in different modalities: the sound of a clarinet, the smell of mothballs. Then there are bodily sensations, from pains to orgasms; mental images that are conjured up internally; the felt quality of emotion, and the experience of a stream of conscious thought. What unites all of these states is that there is something it is like to be in them. All of them are states of experience. — David Chalmers, Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness

Compare Chalmer's antagonist, Daniel Dennett, who claims:

In Consciousness Explained, I described a method, heterophenomenology, which was explicitly designed to be 'the neutral path leading from objective physical science and its insistence on the third-person point of view, to a method of phenomenological description that can (in principle) do justice to the most private and ineffable subjective experiences, while never abandoning the methodological principles of science. — Daniel Dennett, The Fantasy of First-Person Science

I agree with Chalmers, on the grounds that objective physical sciences exclude the first person as a matter of principle. Many other scholars and academics, including John Searle and Thomas Nagel, agree that Dennett's attempt to account for the first person perspective in objective terms, is conceptually flawed from the outset. Hence the satirical depiction of Dennett's book by Searle et al as 'Consciousness Ignored'. -

Nice little roundup of the state of consciousness studiesENOUGH SNARK ALREADY. I deleted the last post as it was blatantly abusive. Unless there are more constructive contributions to be made this thread will be locked.

suddenly you all seem to be reading papers on biosemiosis — apokrisis

This is mainly because of your contributions to the forum so as to provide some background to the subject for those lacking it, to better understand what you are talking about, which goes over the heads of many contributors here. -

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum - an introduction threadWelcome Leontiskos. I too am interested in the Platonist tradition and Christian philosophy. I'm inclined towards idealism with an interest in the classical traditions of philosophy. By the way, don't overlook the Help articles which provide useful tips and pointers to use of the Forum software.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum