Comments

-

Bernard Williams and the "Absolute Conception"the View from Nowhere puts some very peculiar demands on us as denizens of "the world." If "all happening and being-so is accidental," nothing we say in philosophy can escape this. It's all "local," in Williams' terms. "What makes it non-accidental [that is, what makes the Absolute Conception absolute, or unconditioned] cannot lie in the world, for otherwise this would again be accidental." So, how could we meet this demand? — J

It’s important to recall that The View from Nowhere is itself a critique of the limits of scientific objectivity. Nagel’s argument is that while the drive toward objectivity is crucial, it also distorts — especially when we try to abstract away the subject entirely: the world can't be reduced to “what can be said from no point of view.” At some level, the subjective standpoint is indispensable. He’s says he's not advocating idealism, but insisting that the nature of being has an ineliminably subjective ground or aspect (although that is what I think both idealism and phenomenology actually mean.)

In this, Nagel approaches something like a dialectic: not a fusion of subjective and objective, but a dialogical relationship between them. There’s a similarity with a schema given by Zen teacher Gudo Nishijima Roshi in his commentary on Dōgen (the founder of the Sōtō Zen sect). In To Meet the Real Dragon Nishijima describes a fourfold structure of philosophical reflection, which he calls 'Three Philosophies and One Reality'. He says that everything in life can be seen through these perspectives:

- Theoretical — the abstract or subjective standpoint

- Objective — the empirical or material standpoint

- Realistic — the synthesis of the two, lived and integrated

- Ineffable — opening toward the ungraspable real

Nishijima emphasizes that these modes are not to be collapsed into each other. Each is partial, and reality overflows even their synthesis. Reality, in this view, is not reducible to any standpoint — not even to a dialectic — but it must be met, not captured. (Hence the uncompromising emphasis on practice in Zen schools.)

What this offers, perhaps, is a different way of engaging the demand for the unconditioned. Not by striving for a “view from nowhere” in the sense of Archimedean objectivity, but by learning to move fluidly among perspectives without assuming any one of them is exclusive. If there is an Absolute, it does not speak to us in the voice of a single register. It’s approached only through this layered reflection — and perhaps not known as much as embodied.

I think this is the reason why the Western philosophical tradition struggles with these questions — shaped, as it has been, by all-or-nothing theological categories, especially since the Reformation: belief or unbelief, salvation or damnation, truth or heresy. Nondualism allows for a more nuanced philosophical stance — one that doesn’t demand total certainty, but also doesn’t surrender to relativism:

Whether one tries to find an ultimate ground inside or outside the mind, the basic motivation and pattern of thinking is the same, namely, the tendency to grasp. In Madhyamika (Middle Way Buddhist philosophy) this habitual tendency is considered to be the root of the two extremes of "absolutism" and "nihilism." At first, the grasping mind leads one to search for an absolute ground — for anything, whether inner or outer, that might by virtue of its "own-being" be the support and foundation for everything else. Then, faced with its inability to find any such ultimate ground, the grasping mind recoils and clings to the absence of a ground by treating everything else as illusion. — The Embodied Mind, Varela, Thompson, Rosch, First Edition, p143

Also see: Three Philosophies and One Reality, Gudo Nishijima Roshi.

@Leontiskos @Fire Ologist -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?A thermostat is an instrument, designed by humans for their purposes. As such, it embodies the purposes for which it was designed, and is not an object, in the sense that naturally-occuring objects are.

How are we (as 'agents', whatever that means) fundamentally different than any other object, in some way that doesn't totally deny the physicalist view? — noAxioms

'In philosophy, an agent is an entity that has the capacity to act and exert influence on its environment. Agency, then, is the manifestation of this capacity to act, often associated with intentionality and the ability to cause effects. A standard view of agency connects it to intentional states like beliefs and desires, which are seen as causing actions.'

Physicalism has to account for how physical causes give rise, or are related to, intentional acts by agents. But then, the nature of so-called fundamental objects of particle physics - those elementaruy objects from which all else is purportedly arises - itself seems ambiguous and in some senses even 'observer dependent'.

Hence your thread! Which, incidentally, I've most enjoyed. (And belatedly, sympathies for your mother. Mine too was ill for a long while.) -

Bernard Williams and the "Absolute Conception"Science’s power is, among other things, it is predictable and verifiable as an independent authority — Antony Nickles

But aren’t the limits of science also the limits of empiricism? That is: science deals with contingent facts — with what happens to be the case. It excels in explicating the conditioned and the observable, but it brackets questions about the unconditioned or the unconditional — questions that point toward what must be the case if anything is to appear at all, or what cannot not be the case. These are, in an older register, questions about the Absolute. Just the kinds of questions which positivism eschews.

That’s why I introduced the notion of the unconditioned. There’s a conceptual kinship between the unconditioned and what philosophers have called the unconditional — the necessary, the absolute, the ground that is not itself grounded. But empirical science, by its own design, isn’t structured to accomodate that. It works within a domain of contingencies, not ultimates. That’s not a criticism — it’s part of its power — but it is a limit. And as I said before, that limit has become like an unspoken barrier in many ways.

Wittgenstein, at the end of the Tractatus, makes a similar point:

The sense of the world must lie outside the world. In the world everything is as it is and happens as it does happen. In it there is no value—and if there were, it would be of no value.

If there is a value which is of value, it must lie outside all happening and being-so. For all happening and being-so is accidental.

What makes it non-accidental cannot lie in the world, for otherwise this would again be accidental.

It must lie outside the world. — TLP 6.41–6.522

Which raises the key question: what lies outside the world — not as a factual object or hidden variable, but as the condition for intelligibility itself? It’s not a thing, not an empirical entity. And yet philosophy (in its reflective capacity) can’t help but trace the contours of what it cannot fully name — whether it’s called the unconditioned, the transcendental, the One, or the Ground. Not a thing, but not nothing.

This isn’t a claim to “absolute knowledge,” but an acknowledgment that some form of orientation toward the unconditioned may be a necessary feature of any philosophical reflection that seeks to account for intelligibility, normativity, or value without falling into relativism. So, his 'that of which we cannot speak' is not the 'taboo on metaphysics' that the Vienna Circle took it to be - as Wittgenstein himself said:

There is indeed the inexpressible. This shows itself; it is the mystical. — 6522

(See also Wittgenstein, Tolstoy and the Folly of Logical Positivism, Stuart Greenstreet, originally published by the British Wittgenstein Society.) -

The Authenticity of Existential Choice in Conditions of Uncertainty and FinitudeThat is, over virtually every decision, every decision hangs the realization that you are not eternal.

I wonder: "isn't this exactly what creates colossal tension inside us and sets the very thirst to do something, and not to do it?" — Astorre

But some are much more aware of that finitude than others, aren't they? There are a lot of people that barely take into account, I don't know, the fact that they might go to jail, when about to do something. Whereas there are others, like yourself presumably, who are very much aware of their finitude, or you might say, mortality. Very much as suggested by Tillich's 'ultimate concern' or Heidegger's 'being unto death'.

But overall, I agree with you. For your info, it is also what the current large langage models would say:

The idea that not knowing is what enables authentic choice aligns with existentialist thought (e.g., Kierkegaard, Heidegger). For humans, finitude and uncertainty are the conditions under which meaning arises. In that context, the claim that death and ignorance ground authenticity is philosophically resonant.

LLMs generate outputs based on training data and probabilistic models. Even when simulating uncertainty (e.g., with temperature settings), the range of outputs is still bounded by patterns in the data. There is no "I" that chooses; there is no inwardness. Thus, what you call existential choice—rooted in mortality, anxiety, ambiguity—has no analogue in AI. LLMs don’t care, and without concern or dread, there is no authentic commitment. For them, there's nothing at stake. — ChatGPT

That's from the horse's mouth ;-) -

The Authenticity of Existential Choice in Conditions of Uncertainty and Finitudewhat if the basis of such human behavior, unlike computer behavior, lies in the unknown for a person of his own ultimate goal, and the desire to act (make a decision without a task) is based on a person's understanding of his own finitude? — Astorre

Hi Astorre, welcome to the Forum, very good questions. I don't know if 'awareness of one's own finitude' is an explicit consideration for many people, although knowing that there's a lot they don't know might be. In any case, I agree with your intuition that the basis of human actions and decisions, is quite different to how AI systems operate - in fact, I'm sure you would find that most of the current LLMs would agree! (never mind the irony of that)

There's an interesting OP in the current edition of Philosophy Now, Rescuing Mind from the Machines, which makes an argument similar to yours. -

On Purposeworth looking at it in the context. She's using 'compute' in the metaphorical sense of taking in information and transforming it for a useful purpose, as metabolism does.

-

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?Because we make judgements, for starters. We decide, we act, we perform experiments, among other things. What object does that? ~ Wayfarer

I can think of several that might do all that, — noAxioms

The question stands - what kinds of objects think, decide, act, perform experiments? AI is not a naturally occurring object, nor does it possess agency in the sense of the autonomous intentions that characterise organisms. It operates within a framework of goals and constraints defined by humans.

Bearing all that in mind, the original question was:

How are we (as 'agents', whatever that means) fundamentally different than any other object, in some way that doesn't totally deny the physicalist view? — noAxioms

So - AI systems embody or reflect human agency, so again, they're not objects, in the sense that the objects of the physical sciences are.

You can dodge the question of agency so easily, nor how physicalist theories struggle to account for it.

(In philosophy, an agent is an entity, typically a person, that has the capacity to act and make choices. This capacity is referred to as agency. Agency implies the ability to initiate actions, exert influence on the world, and be held responsible for the consequences of those actions.) -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?I thought that might be the response. But AI is an instrument which has been created by human engineers and scientists, to fulfil their purposes. It's not a naturally-occuring object.

-

Consciousness is FundamentalMost threads dealing with consciousness, regardless of their intent, soon turn into debates about Physicalism vs Idealism vs Panpsychism vs... I obviously can't keep the thread on the track, or system of tracks, I want. — Patterner

But that is the nature of this subject. Panpsychism, by definition, is a philosophical theory of mind, alongside materialism and idealism. You don't get to change that. It's like saying, let's discuss supply-side economics, without talking about economics.

There is no detail to consciousness. The consciousness of different things is not different. Not different kinds of consciousness, and not different degrees of consciousness. There's no such thing as higher consciousness. — Patterner

This is self-evidently false, and yet you then declare that you have no interest in discussing the possibility that it is mistaken with anyone. You basically want to dictate what others might say, in advance.

In short: Consciousness is subjective experience. I have heard that wording more than any other, but I prefer Annaka Harris' "felt experience". — Patterner

This is a critique of Harris' panpsychism: Panpsychism: Bad Science, Worse Philosophy, Medium (requires registration).

This article critically examines Annaka Harris’s contribution to the popular resurgence of panpsychism—the view that consciousness is a fundamental property of matter. While philosopher Philip Goff argues for panpsychism as an alternative to the explanatory failure of materialism, Harris claims to remain a materialist while advocating for a form of consciousness-as-inherent-to-matter. To address the "combination problem"—how scattered micro-qualia could yield a unified conscious subject—she denies the existence of the self altogether. In her view, consciousness is just content arising, like bubbles in a pot, with no unified subject or experiencer. (My view is that in this, she draws on a popular but inaccurate interpretation of Buddhist philosophy, likely taken from her husband Sam Harris, who espouses a kind of Buddhist materialism: the notion that "the Buddha says there is no self." In fact, the Buddhist principle is that "all phenomena are devoid of self" (anatta), which is a much more subtle principle. Saying there is no self tout court completely undercuts any possibility of moral agency. It is, in fact, a form of nihilism, which was always rejected in Buddhism.)

The article contends that Harris’s move dissolves the very phenomenon needing explanation—coherent, first-person conscious experience—by asserting it to be an illusion. Moreover, it notes that the appeal to panpsychism, while framed as scientifically open-minded, ends up preserving the ontological blind spots of materialism in a new guise. Her reliance on common-sense distinctions (e.g., socks and rocks aren’t conscious) sits uncomfortably beside her claim that all matter entails consciousness.

By way of concusion, the author suggests that if one truly wishes to move beyond materialist assumptions, it must be done with a philosophical framework—such as idealism—that can account for the unity, structure, and intelligibility of consciousness, rather than erasing them in favor of a scattered field of unintelligible qualia. -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?Because we make judgements, for starters. We decide, we act, we perform experiments, among other things. What object does that? ~ Wayfarer

I can think of several that might do all that, — noAxioms

Well, name one. -

On PurposeKudos for clearly & concisely summarizing a vexing question of modern philosophy. Ancient people, with their worldview limited by the range of human senses, unaided by technology, seemed to assume that their observable Cosmos*1 behaves as-if purposeful, in a sense comparable to human motives. "As-If" is a metaphorical interpretation, not an empirical observation. — Gnomon

Thanks for that. Maybe this is because pre-moderns did not have the sense of separateness or otherness to the Cosmos that the modern individual has. In a sense - this is something John Vervaeke discusses in his lectures - theirs was a participatory universe.

I've been reading an interesting book, a milestone book in 20th c philosophy, The Phenomenon of Life, Hans Jonas (1966). A brief précis - 'Hans Jonas's The Phenomenon of Life offers a philosophical biology that bridges existentialism and phenomenology, arguing that life's fundamental characteristics are discernible in the very structure of living beings, not just in human consciousness. Jonas proposes a continuity between the organic and the mental, suggesting that the capacity for perception and freedom of action, culminating in human thought and morality, are prefigured in simpler forms of life.' That is very much the theme of the OP. It is expanded considerably in Evan Thompson's 'Mind in Life', a much more recent book (2010) which frequently refers to Jonas' book.

Another point that Jonas makes in the first essay in the book is that for the ancients, life was the norm, and death an anomaly that has to be accounted for - hence the 'religions of immortality' and belief in the immortality of the soul:

That death, not life, calls for an explanation in the first place, reflects a theoretical situation which lasted long in the history of the race. Before there was wonder at the miracle of life, there was wonder about death and what it might mean. If life is the natural and comprehensible thing, death-its apparent negation-is a thing unnatural and cannot be truly real. The explanation it called for had to be in terms of life as the only understandable thing: death had somehow to be assimilated to life. ...

... Modem thought which began with the Renaissance is placed in exactly the opposite theoretic situation. Death is the natural thing, life the problem. From the physical sciences there spread over the conception of all existence an ontology whose model entity is pure matter, stripped of all features of life. What at the animistic stage was not even discovered has in the meantime conquered the vision of reality, entirely ousting its counterpart. The tremendously enlarged universe of modern cosmology is conceived as a field of inanimate masses and forces which operate according to the laws of inertia and of quantitative distribution in space. This denuded substratum of all reality could only be arrived at through a progressive expurgation of vital features from the physical record and through strict abstention from projecting into its image our own felt aliveness. — The Phenomenon of Life, Essay One, Pp 9-10

As you implied, the nay-sayers seem to be looking through the wrong end of the telescope. — Gnomon

More the case that they forget that they're the ones who made the telescope.

it's doubtful that "meaning" (purpose) is anything other than a (semantic) property, or artifact, of "observers" and not, as you suggest, inherent in nature. — 180 Proof

You're seeing it from an anthropocentric sense of what meaning and purpose are. The point of the OP is that meaning, purpose and intentionality manifest at the most rudimentary stages of organic life. As soon as living processes begin to form, the fundamental requirement is for them to maintain separateness from the environment, otherwise they're simply subsumed into the thermodynamically-driven processes going on around them. That is the broader sense of intentionality that the OP is arguing from, not the projected meaning and purpose usually associated with theism and denied by atheism.

Again, this recent presentation, How the Universe Thinks Without a Brain, Claire L. Evans, is definitely worth watching in this context. 'To be, is to compute'. -

Consciousness is FundamentalYou haven’t presented any reason for why you would think that.

— Wayfarer

Not in this thread. — Patterner

Well, you should. If you want to make an OP it has to stand on its own two feet, especially for a major topic such at this.

I don't think you're actually open to discussions. You're stipulating what others must accept as the case, before having the discussion. You say, you don't want to engage in the back-and-forth or give reasons for why you are saying it. So - are you talking to yourself? -

Consciousness is FundamentalThe idea is that consciousness is always present. In everything, everywhere, at all times — Patterner

You haven’t presented any reason for why you would think that. -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?Standard QM by itself is silent, I believe, on what is an 'observer'. — boundless

Robert Lawrence Kuhn (Closer to Truth) has a series of interviews on 'the physics of the observer'. -

Bernard Williams and the "Absolute Conception"More that they’re outside the electric fence.

-

On PurposeTake a look at the video I just posted into the reply above yours. it is *exceedingly* interesting.

-

On PurposeIntention requires a mind and a mind requires a nervous system. At that point, we've moved out of the realm of biology and into neurology, ethnology, and psychology. — T Clark

I watched an exceedingly interesting talk recently ('How the Universe Thinks without a Brian') on slime moulds and other very primitive organism, that utterly lack brains and nervous systems, but which nevertheless form memories in respect of their environment. For example, Physarum polycephalum can learn the patterns of periodic environmental changes and adjust its movement accordingly—despite being just a giant single cell.

This doesn’t mean it has a mind in the conscious sense, but it strongly suggests that intentional-like behavior—orientation toward what matters to it —can appear even before anything like a nervous system arises. That’s part of what I meant by “intentionality in a broader sense than conscious intention. It’s not about inner deliberation, but about the intrinsic organization of living systems around meaningful interaction with their environment.

This is why I think the boundary between biology and psychology isn’t as clean as the classical model would have it. A lot of the resistance to this idea, I think, comes from our folk understanding of intentionality: that it has to be something like what I am capable of thinking or intending. But that’s a very anthropocentric benchmark. The broader point from fields like enactivism and biosemiotics is that purposeful behavior need not be consciously formulated to be real—it can be embodied, embedded, and evolutionary long before it’s verbalized.

So when I say that purpose is implicit in life, I’m not projecting human psychology downward. I’m pointing out that living systems are organized around the kind of concern that enables them to persist, adapt, and flourish. That’s not a metaphor; it’s what they do.

I think this (i.e. Jacques Monod) is clearly incorrect as a matter of science and not of philosophy. — T Clark

As do I! -

On PurposeI might add—and as you probably know—Nagel at least sketches a kind of naturalistic teleology in Mind and Cosmos: the idea that human beings are, in some sense, the universe becoming conscious of itself. That motif actually appears across many different schools of philosophy and even within science itself. Think of Niels Bohr’s remark: “a physicist is an atom’s way of looking at itself.”

Now, that doesn’t amount to a fully formed metaphysics, but it at least opens a way of thinking that challenges the view of humanity as a cosmic fluke—an accidental intelligence adrift in a meaningless expanse. -

On Purpose"Does existence have a purpose?" -- "whether life, the universe, and everything is in any sense meaningful or purposeful." Were you trying to get to a purpose that is actually meaningful for humans? I don't think your OP addressed that — J

You're right to note that I didn't try to answer the question of human purpose directly. My intention was more foundational: to challenge the premise that the universe is inherently meaningless by pointing to the ubiquity of purposive activity in life itself, starting at the cellular level.

You could say this is a “thin end of the wedge” strategy. If even the simplest organisms act in goal-directed ways, then purposefulness is not merely a projection of the human mind onto an otherwise purposeless background—it’s already there, intrinsic to the structure of life. My aim was to question the modern assumption (popular among positivists) that purposiveness is somehow unreal or merely heuristic.

I do think this ultimately has implications for human purpose—but I didn't try to develop that in this piece. What I wanted to show is that the universe, far from being “purposeless,” brings forth beings whose very mode of existence is purposive. That alone, I think, should shift the philosophical burden of proof. -

On PurposeI don't think there is sufficient evidence to say that there are 'purposes' outside living beings. — boundless

Nor I, but that’s why I said that the argument is kind of a red herring - if you were looking for purpose in the abstract, what would you be looking for? But I’m interested in the idea that the beginning of life is also the most basic form of intentional (or purposive) behaviour - not *consciously* intentional, of course, but different to what is found in the inorganic realm. (The gap between them being what Terrence Deacon attempts to straddle in Incomplete Nature.)

As for the anthropic principle - that general argument provides a meaningful counter to the kinds of ideas expressed in (for example) Jacques Monod ‘Chance and Necessity’. Monod, a Nobel laureate in biology, argued that life, and indeed human existence, is a product of "pure chance, absolutely free but blind." He saw genetic mutations, the ultimate source of evolutionary innovation, as random and unpredictable events at the molecular level. While natural selection then acts out of "necessity" (the necessary outcome of differential survival based on adaptation), the initial raw material for selection (mutation) is blind and without foresight or purpose. A central tenet of Monod's philosophy was the forceful rejection of any form of teleology (inherent purpose or design) in the universe, especially concerning the origin and evolution of life. He argued that science, particularly molecular biology, had revealed a mechanistic universe governed by objective laws, where the biosphere is a "particular occurrence, compatible indeed with first principles, but not deducible from those principles and, therefore, essentially unpredictable.

The strong anthropic principle (that the universe is such that life must appear) mitigates against the possibility of life being understandable as a sheer accident. It suggests that the universe is structured such that life (or observers) is either a necessary or at least a highly probable outcome. Some readings explicitly embrace a form of teleology, positing a "design" or "purpose" for the universe's life-permitting properties. In any case, it challenges the cardinal role of 'blind chance' typical of Monod's (and Dawkins') style of scientific materialism.

But here's my main question: Let's grant that biological life is purposive in all the ways you say it is. Let's even grant, which I doubt, that all living creatures dimly sense such a purpose -- gotta eat, gotta multiply! The question remains, Is that the kind of purpose worth having for us humans? Is that what we mean by the "meaning of life"?

Indeed -- and I think Nagel goes into this as well -- it's precisely the pointlessness of the repetitive biological drives you cite, that causes many people to question the whole idea of purpose or meaning. It looks absurd, both existentially and in common parlance: "I'm alive so that I can . . . generate more life? That's it? Who cares?" Cue the Sisyphus analogy . . .

Any thoughts about this? — J

That's a fundamental question of philosophy. It's basically a 'what's it all about?' question. Nagel said

Darwin enabled modern secular culture to heave a great collective sigh of relief, by apparently providing a way to eliminate purpose, meaning, and design as fundamental features of the world. Instead they become epiphenomena, generated incidentally by a process that can be entirely explained by the operation of the non-teleological laws of physics on the material of which we and our environments are all composed.

It's taken for granted nowadays that evolutionary naturalism is a philosophy of existence, but it's not.. It is a scientific theory of the evolution of species. I should say, what prompted this OP was a Medium essay by Massimo Piggliuci The Question of Cosmic Meaning or Lack Thereof (may require account to read). He takes on Nagel but then draws on the basic Monod-style materialism I refer to above. The germ of this OP came from his response to a comment of mine, where he breezily dismisses any idea of purpose as being 'explained by teleonomy'. Perhaps I have too have been breezy, but really, the distinction between 'actual' and 'apparent purpose' is a slim reed on which to support such argument!

In any case, getting back to your question - are we really only defined in terms of the terminology of evolutionary biology (the 'four f's' of feeding, fighting, fleeing and reproduction)? I don't think evolutionary theory, as such, provides the basis for a great deal more than that. Which is why I argue that h.sapiens transcends purely biological determination. Hence, philosophy! (along with art, science, literature, and a great deal else.)

Some interpretations of quantum mechanics bring the observer into the equation, others do not — T Clark

They don't really 'bring the observer into the equation'. The problem is precisely that 'the equation' makes no provision for the act of observation. The famous wave-function equation provides predictive accuracy as to where a particle might be found, but the actual finding of it is not something given in the mathematics. That is where the observer problem originates. (The 'many worlds' interpretation attempts to solve this by saying that every possible measurement occurs in one of the possible worlds.)

Regarding whether organisms really act purposefully, or only as if they do - this is central to the whole debate about teleology and teleonomy. (The Wikipedia entry on teleonomy is worth the read.)

you can't answer scientific questions with metaphysics and you can't answer metaphysical questions with science. — T Clark

What I said.

I think that is Wayfarer’s point. — Joshs

Pretty much! I like that expression I've picked up from enactivism, 'the salience landscape'. Might do another OP on that. -

Bernard Williams and the "Absolute Conception"philosophy is like science with no balls. — Fire Ologist

It’s more that most of the intellectual resources of Western philosophy became concentrated on science (‘natural philosophy’) to the extent that the other aspects of it withered away. Banno has referred to surveys which show that a very small percentage of the academic philosophy profession defend philosophical idealism. Most seem to align with some form of physicalism, such as non-reductive physicalism (Davidson et el). So the lexicon for alternative philosophical conceptions hasdried upbeen deprecated - the presumption is that the word is physical (whatever that means) and science is the way to investigate it (wherever that leads). Meanwhile philosophers can talk quietly amongst themselves at conferences and publish learned papers for each other.

Regarding frameworks, I certainly accept that there are meaningful frameworks, or rather, domains of discourse, but again, the implicit presumption will generally be that these will be subsumed under the heading of natural science (or ‘naturalism’ in philosophy). But that is why I will call out to Indian and current idealist philosophy from time to time, as their philosophies have not on the whole been subsumed under naturalism, to the degree that Anglo philosophy has. -

Does anybody really support mind-independent reality?Cognitive science shows that what we experience as 'the world' is not the world as such - as it is in itself, you might say - but a world-model generated by our perceptual and cognitive processes. So what we take to be "the external world" is already shaped through our cognitive apparatus. This suggests that our belief in the world’s externality is determined by how we are conditioned, biologically, culturally and socially, to model and interpret experience, rather than by direct perception of a mind-independent domain.

— Wayfarer

OK, I agree with all that, but our belief being shaped by perceptions does not alter what is, does not falsify this externality, no more than the physicalist view falsifies the idealistic one. — noAxioms

The assumption that the object is at it is, in the absence of the observer, is the whole point. That is the methodological assumption behind the whole debate. The fact that there is an ineliminable subjective aspect doesn’t falsify that we can see what is, but it does call the idea of a completely objective view into question.

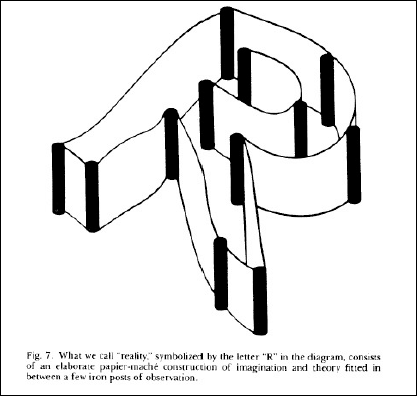

From John Wheeler, Law Without Law. The caption reads ‘what we consider to be ‘reality’, symbolised by the letter R in the diagram, consists of an elaborate paper maché construction of imagination and theory fitted between a few iron posts of observation’.

But the philosophical question is about the nature of existence, of reality as lived - not the composition and activities of those impersonal objects and forces which science takes as the ground of its analysis. We ourselves are more than objects in it - we are subjects, agents, whose actions and decisions are of fundamental importance ~ Wayfarer

This part seems to be just an assertion. How are we (as 'agents', whatever that means) fundamentally different than any other object, in some way that doesn't totally deny the physicalist view? — noAxioms

Because we make judgements, for starters. We decide, we act, we perform experiments, among other things. What object does that? -

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of GodThis context is crucial because it provides fertile ground for a person to grow into knowledge and understanding and become one of the more advanced students sitting alongside them. — Punshhh

:100: It's the essence of culture. -

Bernard Williams and the "Absolute Conception"Do you have an opinion about this "more"? How would you answer your own question? I'm guessing you would point to a wisdom-tradition response that "gestures beyond" this kind of philosophy. . . ? (as suggested by your subsequent post, from which I quote below) My own answers would be similar. — J

Quite right. But Greek philosophy was also animated by just that ideal. See Becoming God: Pure Reason in Early Greek Philosophy, Patrick Lee Miller:

Becoming god was an ideal of many ancient Greek philosophers, as was the life of reason, which they equated with divinity. This book argues that their rival accounts of this equation depended on their divergent attitudes toward time. Affirming it, Heraclitus developed a paradoxical style of reasoning-chiasmus-that was the activity of his becoming god. Denying it as contradictory, Parmenides sought to purify thinking of all contradiction, offering eternity to those who would follow him. Plato did, fusing this pure style of reasoning-consistency-with a Pythagorean program of purification and divinization that would then influence philosophers from Aristotle to Kant. Those interested in Greek philosophical and religious thought will find fresh interpretations of its early figures, as well as a lucid presentation of the first and most influential attempts to link together divinity, rationality, and selfhood.

Plainly, 'reason' had a very different meaning in that context than it does for us. Not the tidy propositional format of 'justified true belief' but the basis of an all-encompassing way of life. Of course there's been much water under the bridge, there's no way to re-inhabit the ancient mind, but at least the lexicon of ancient philosophy provides a better vocabulary than does modern.

In Neoplatonism:

- The One is absolutely simple — beyond all predication, even being itself (beyond existence, as Plotinus puts it).

- So cannot be known in the discursive or propositional sense.

- But because all things emanate from the One, and because the soul is ultimately a trace of it, we can become united with it by a kind of reversion or return (epistrophe).

- This is not knowledge about the One, but an ascent — what Plotinus described as the “flight of the alone to the Alone.”

There are similes in Buddhism and Vedanta. In Vedānta, Brahman is not an object of knowledge — it is the ground of the knower. The jñāni (knower) realizes his/her identity as “I am Brahman.” In Buddhism, ultimate truth (paramārtha-satya) cannot be framed in conceptual thought. It requires a transformative mode of knowing that is not reducible to cognition, but is existential or participatory, knowing by being. This is what Pierre Hadot called philosophy as a way of life — and what the early Greek philosophers likely meant by "know thyself”. -

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of GodHis scope is limited to outlining the "nature of man". — Relativist

But the point stands. He starts his book Materialist Philosophy of Mind with the assertion that man is an object, which is wrong on so many levels that it’s not even worth discussing. -

Bernard Williams and the "Absolute Conception"If you like you can replace "knowledge" with "absolute knowledge" and then ask J what the heck "absolute knowledge" is supposed to be — Leontiskos

I can’t help think it must be something like gnosis or one of its cognates - subject of that rather arcane term 'gnoseology' which is comparable to 'epistemology' but with rather more gnostic overtones. In any case, it is knowledge of the kind which conveys a kind of apodictic sense, although that is a good deal easier to write about than to actually attain. -

Bernard Williams and the "Absolute Conception"Thus we have multiple uses or senses of know happening at once without distinction, “we have to know [as in: understand (be aware of) the criteria] that we have [for] an absolute conception of the world… To ask not just that we should know [be aware], but that we should be [absolutely certain] that we know [have the right criteria]. — Antony Nickles

I linked earlier to an article by Steven Shakespeare on the unconditioned in philosophy of religion. One of his key points is that “the unconditioned” might serve as a more open-ended alternative to the term “God” in philosophical discourse, especially when trying to speak about the absolute without presuming a theistic framework. The unconditioned, as he frames it, is not just another necessary being in all possible worlds—it’s that in virtue of which any world, or any necessary being, is intelligible at all.

This seems to resonate with the question Williams raises: can philosophy speak meaningfully of something absolute without claiming to know it in the apodictic, Cartesian sense? Maybe what’s needed isn’t absolute knowledge but an orientation toward the limits of conditioned thought—a recognition that philosophy, at its best, gestures beyond what it can fully capture.

I’m not claiming any esoteric insight, but I’d suggest that to speak of the unconditioned meaningfully may require not just analysis but transformation: something more like philosophical detachment than scientific objectivity. And that, I think, also points toward a different conception of knowledge than the scientific—one closer to insight or self-knowledge. It’s not often found in the dominant strains of Anglo-American philosophy, but it’s much more characteristic of certain strands of European and Asian thought. -

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of GodSo he's not deferring to science to answer the question of what the "nature" of mind is- he's drawing the conclusion as a philosopher. And his account merely aims to show that mental activity is consistent with physicalism (a philosophical hypothesis). — Relativist

But all of his work is based on the presumption that science is the definitive source of knowledge for what the mind might be. It's a philosophy based on solely on science, rightly criticized as 'scientism' ' the belief that science and the scientific method are the best or only way to understand the world and gain knowledge'. -

Bernard Williams and the "Absolute Conception"Williams is asking, If philosophy asserts this, is it asserting a piece of absolute knowledge? It's certainly a striking and important assertion, if true; the question is, what is its claim to being knowledge, and of what sort? Is it "merely local" -- that is, the product of a philosophical culture which cannot lay claim to articulating absolute conceptions of the truth? — J

So if it’s a philosophical claim, then how is it to be adjudicated? Surely that would require some framework within which the expression “philosophical absolute” is meaningful. I suppose when Williams asks whether, if we were to possess such an insight, we must know we possess it, he’s invoking the Cartesian expectation that a genuine absolute insight would be, as Descartes claimed of the cogito, apodictic — self-certifying by virtue of its subject matter.

But if we never say more than “here’s what an absolute would be like if there were one,” have we said anything of consequence? Or would it have been better not to have asked the question?

I think what we're experiencing here is a version of what Richard Bernstein called the Cartesian anxiety: the fear that unless we can affirm an absolute with certainty, we’re condemned to relativism. But perhaps that anxiety itself arises from a false dichotomy: philosophical reflection can meaningfully trace the limits of conditioned knowledge without pretending to stand outside of it. When I said that 'the natural sciences cannot be complete in principle,' I'm not making a metaphysical declaration from on high but reflecting critically — and necessarily — on the conditions of intelligibility that science presupposes but doesn't (and doesn't necessarily need to) account for. That stance doesn't claim to possess the absolute — but it does require that we be open to 'the unconditioned' as a necessary item in the philosophical lexicon. Which we're generally not!

(Here's a relevant piece of analytical philosophy on this subject, The unconditioned in philosophy of religion, Steven Shakespeare, which makes the case for the necessity of 'the unconditioned' in place of a putative deity in this debate.) -

Bernard Williams and the "Absolute Conception"He points to a familiar problem: We would like some sort of absolute knowledge, a View from Nowhere that will transcend “local interpretative predispositions.” But what if we accept the idea that science aims to provide that knowledge, and may be qualified to do it? What does that leave for philosophy to do? — J

What is problematic in that formulation is the hidden or implicit metaphysics in the modern conception of science. A part of that is the assumption that the natural sciences, or nature, or our conception of nature, is in principle complete or able to be completed, as others have said. But then these founding assumption are themselves ignored, meaning that the natural sciences cannot be complete in principle, as they neglect the very foundational assumptions upon which they rest.

Scientific objectivity is methodological - it's about designing studies, collecting data, and interpreting results in ways that minimize bias and personal influence. It involves using controlled experiments, peer review, replication, and statistical analysis to separate reliable findings from subjective impressions. The goal is to let the evidence speak for itself, regardless of what the researcher might personally prefer to find.

Philosophical detachment, on the other hand, is more about an existential stance toward knowledge and experience. It involves stepping back from immediate emotional investment or personal attachment to outcomes. A philosopher might cultivate detachment to see issues more clearly, to avoid being swayed by passion or self-interest, or to maintain intellectual humility about the limits of human understanding.

The key difference is that scientific objectivity is primarily about method and process, while philosophical detachment is about attitude and perspective. So the former provide criteria which can be validated in the third person, whereas the latter requires subjective commitment. So modern philosophy finds itself caught between two impulses: the traditional philosophical concern with wisdom, meaning, and understanding (which seems to require some form of first-person insight), and the modern demand for empirical rigor and third-person validation. The result is that philosophical detachment itself becomes suspect - how can you verify that someone has achieved it? How can you test whether it actually leads to truth rather than just personal satisfaction? Which explains why so much of contemporary philosophy focuses on conceptual analysis, logical argumentation, and empirically-informed theories rather than the exploration of ways of being.

So, there's real difference between the scientific and the philosophical attitude towards these questions, but it's very hard to articulate in terms that are acceptable to the former. From a scientific perspective, if you can't specify what would count as evidence for or against a claim, if you can't operationalize your concepts, if your insights can't be independently verified - then you're not really saying anything meaningful. The scientific framework becomes the measure of what counts as legitimate knowledge.

And as the scientific framework is by definition is reliant on conditions, then nothing whatever can be said about any supposed philosophical absolute which by definition is unconditional. That's the problem in a nutshell. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)But now I guess the time to make those beautiful trade agreement before the "liberation" tariffs set in is coming to an end. And Trump has done... one with the UK? — ssu

Just today, he's crashed the negotiations, sending out his inane missives on his social media platform that he's slapping 30% tarriffs on EU and Mexico, who were in the middle of intricate and apparently promising negotiations to lower trade barriers.

It's clear Trump has no idea what he's doing with these tarriffs. He's driven by pique, whim, imagined vengeance, and a total misunderstanding of basic economics. The share market is 'irrationally exuberant' only because of the belief that he'll back down again, but if he doesn't, and the resulting inflation and contraction begins to appear, then it might be a very different outcome. -

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of GodWhere did Armstrong say that all questions should be deferred to science? — Relativist

What does modern science have to say about the nature of man? There are, of course, all sorts of disagreements and divergencies in the views of individual scientists. But I think it is true to say that one view is steadily gaining ground, so that it bids fair to become established scientific doctrine. This is the view that we can give a complete account of man in purely physico-chemical terms. — The Nature of Mind, p1

Doesn't leave a lot of room for equivocation. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)Surely some media somewhere must be tracking the Trump Damage List? Trump is attacking so many fundamentals that it’s hard to keep track:

- Democratic institutions (i.e. purging of civil services, stacking the bench, withholding congressionally-approved funds)

- Abolition of agencies (U.S.A.I.D., Voice of America, public broadcasting)

- The constitution - by undermining the authority of Congress and the Judiciary

- Science and science education - abolition of NIH grants, attacks on vaccination and medical science

- Universities

- Climate Change - abolition of green energy transition, undermining of renewables

- Economics - tariff policies generate inflation and slow economic growth

There are probably many other issues. Surely by this time next year many of these issues will be having serious consequences for a lot of Americans. -

ChatGPT 4 Answers Philosophical QuestionsThanks for that thorough analysis, appreciated. Going on my experience, the models seem to cope with everything I ask of them. I seem to recall in the CNBC video, one of the commentators saying there was a possibility of Apple ofuscating some points to distract from the often-commented fact that its own AI implementation seems a long way behind the pack.

-

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of GodThis is so because "consciousness" (qualia, intention, feeling, or other folk-percepts), in contrast to observation, on occasion might be a consequence but is neither a necessary nor sufficient condition (or operational requirement) of "scientific theorizing". — 180 Proof

You're not seeing the point. The passage is not a 'theory about consciousness'. Read it again:

Husserl believed all knowledge, all science, all rationality depended on conscious acts, acts which cannot be properly understood from within the natural outlook at all — Routledge Introduction to Phenomenology, p143

How can they not be dependent on conscious acts? They all rely on reasoning, rational inference, calculation and judgement.

As to why this can't be understood from 'within the natural outlook', this is because consciousness (or simply 'the mind') never appears as an object for the natural sciences: 'Consciousness should not be viewed naturalistically as part of the world at all, since consciousness is precisely the reason why there was a world there for us in the first place.' It is more accurate to say that the world appears in the mind, than that the mind appears in the world. -

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of GodA clearing, as one of his successors would call it.

-

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of GodHusserl deliberately brackets metaphysical and spiritual claims in the context of the practice of epochē —the suspension of judgment about the existence or non-existence of the external world. This does not mean he denies such claims, but rather that phenomenological analysis proceeds without them, focusing instead on the structures of experience and the intentional acts of consciousness. In that way, he’s not a metaphysician in the traditional sense, and certainly not a “spiritual” philosopher in any confessional or mystical way. But—and this is important—his work touches on the metaphysical at the deepest level, especially in the Crisis, where he discusses the forgotten origins of science in the life-world and argues for a kind of transcendental grounding of meaning and rationality. Meta-metaphysical, if you like.

There’s also a strong Platonic or idealist undercurrent in Husserl’s later thought—his notion of eidetic reduction suggests that essences are real and perceptible to intuition, and not merely empirical generalizations. So while he doesn't affirm metaphysical or spiritual doctrines, his work provides a space for them.

In the context of the discussion with @Relativist, I'm trying to avoid arguing on the basis of 'the spiritual', as that is seen as being the natural opponent of 'the physical'. But that, again, is the shadow of Cartesian dualism, the very divisions of mind and matter, spiritual and physical, that Husserl is careful to avoid, and that I wish to avoid also. -

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of GodEmbracing physicalism as an ontological ground* does not entail deferring all questions to science. — Relativist

That is exactly what David Armstrong and Daniel Dennett do. Where do you differ from them on that score?

Another point I’ve noticed: that you label a very wide range of philosophies ‘speculative’. You’re inclined to say that, even if physicalism is incomplete, anything other than physicalism is ‘speculative’, simply 'an excuse' to engage in 'wishful thinking'. But isn't it possible that this might be because you’re not willing to entertain any philosophy other than physicalism? That it's a convenient way not to have to engage with anything other than physicalism - label it ‘speculative'? And how is that not also 'wishful thinking'?

As for the 'unknown immaterial ground' - what if that 'unknown immaterial ground' is simply thought itself? I know what David Armstrong's answer to that would be: thoughts are brain-states, configurations of neurochemicals, in line with his view that everything about the mind can be explained in terms of physics and chemistry:

What does modern science have to say about the nature of man? There are, of course, all sorts of disagreements and divergencies in the views of individual scientists. But I think it is true to say that one view is steadily gaining ground, so that it bids fair to become established scientific doctrine. This is the view that we can give a complete account of man in purely physico-chemical terms. — The Nature of Mind, D M Armstrong

(Notice also the claim to authority inherent in it becoming 'established scientific doctrine'. The triumphal flourish: 'It's true, because science says it is!')

So, what is the matter with the claim that thoughts are brain-states? Consider Edmund Husserl's criticism of naturalism:

In contrast to the outlook of naturalism, Husserl believed all knowledge, all science, all rationality depended on conscious acts, acts which cannot be properly understood from within the natural outlook at all. Consciousness should not be viewed naturalistically as part of the world at all, since consciousness is precisely the reason why there was a world there for us in the first place. For Husserl it is not that consciousness creates the world in any ontological sense—this would be a subjective idealism, itself a consequence of a certain naturalising tendency whereby consciousness is cause and the world its effect—but rather that the world is opened up, made meaningful, or disclosed through consciousness. The world is inconceivable apart from consciousness. Treating consciousness as part of the world, reifying consciousness, is precisely to ignore consciousness’s foundational, disclosive role. For this reason, all natural science is naive about its point of departure, for Husserl (PRS 85; Hua XXV 13). Since consciousness is presupposed in all science and knowledge, then the proper approach to the study of consciousness itself must be a transcendental one—one which, in Kantian terms, focuses on the conditions for the possibility of knowledge... — Routledge Introduction to Phenomenology, p143

This is not speculative but analytic: naturalism and physicalism ignore the foundational, disclosive role of consciousness at the basis of scientific theorising. Even to develop a theory of how the brain generates or forms or causes the content of thought relies on those conscious actions. And you can't see those activities from the outside - you will never see a true proposition in the data of neuroscience, only images that the expert will need to interpret, in order to judge. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)Big Bad Bill Adds Tax That Could Cripple Wind and Solar Power Generation (New York Times gift link)

Senate Republicans have quietly inserted provisions in President Trump’s domestic policy bill that would not only end federal support for wind and solar energy but would impose an entirely new tax on future projects, a move that industry groups say could devastate the renewable power industry.

The tax provision, tucked inside the 940-page bill that the Senate made public just after midnight on Friday, stunned observers.

“This is how you kill an industry,” said Bob Keefe, executive director of E2, a nonpartisan group of business leaders and investors. “And at a time when electricity prices and demand are soaring.”

The bill would rapidly phase out existing federal tax subsidies for wind and solar power by 2027. Doing so, many companies say, could derail hundreds of projects under development and could jeopardize billions of dollars in manufacturing facilities that had been planned around the country with the subsidies in mind.

Those tax credits were at the heart of the Inflation Reduction Act, which Democrats passed in 2022 in an attempt to nudge the country away from fossil fuels, the burning of which is driving climate change. President Trump, who has mocked climate science, has instead promoted fossil fuels and demanded that Republicans in Congress unwind the law.

But the latest version of the Senate bill would go much further. It would impose a steep penalty on all new wind and solar farms that come online after 2027 — even if they didn’t receive federal subsidies — unless they follow complicated and potentially unworkable requirements to disentangle their supply chains from China. Since China dominates global supply chains, that measure could affect a large number of companies.

“It came as a complete shock,” said Jason Grumet, the chief executive of the American Clean Power Association, which represents renewable energy producers. Soon after the Senate bill was made public, Mr. Grumet said that phones started ringing at 2:30 a.m. on Saturday with “everyone saying, ‘Can you believe this?’”

The new tax “is so carelessly written and haphazardly drafted that the concern is it will create uncertainty and freeze the markets,” Mr. Grumet said.

Even some of those who lobbied to end federal support for clean energy said the Senate bill went too far.

“I strongly recommend fully desubsidizing solar and wind vs. placing a kind of new tax on them,” wrote Alex Epstein, an influential activist who has been urging Republican senators to eliminate renewable energy subsidies. “I just learned about the excise tax and it’s definitely not something I would support.”

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce also criticized the tax. “Overall, the Senate has produced a strong, pro-growth bill,” Neil Bradley, the group’s chief policy officer, posted on social media. “That said, taxing energy production is never good policy, whether oil & gas or, in this case, renewables.” He added: “It should be removed.”

Wind and solar projects are the fastest growing new source of electricity in the United States and account for nearly two-thirds of new electric capacity expected to come online this year. For utilities and tech companies, adding solar, wind and batteries has often been one of the easiest ways to help meet soaring electricity demand. Other technologies like new nuclear reactors can take much longer to build, and there is currently a multiyear backlog for new natural gas turbines.

The repeal of federal subsidies alone could cause wind and solar installations to plummet by as much as 72 percent over the next decade, according to the Rhodium Group, a research firm. The new tax could depress deployment even further by raising costs an additional 10 to 20 percent, the group estimated.

The only voices in favour are fossil fuel energy lobbyists. And, of course, Trump, the universal wrecking ball.

(Also worth noting that Musk, having returned to his sinking ship, thinks it a terrible plan: “The latest Senate draft bill will destroy millions of jobs in America and cause immense strategic harm to our country! It gives handouts to industries of the past while severely damaging industries of the future.” Wish he'd had that realisation last October.) -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)Ok might be hyperbolic but it’s making it much harder to raise lawsuits against executive orders. A dissenting opinion said:

Today’s ruling allows the Executive to deny people rights that the Founders plainly wrote into our Constitution, so long as those individuals have not found a lawyer or asked a court in a particular manner to have their rights protected,” Jackson’s dissent states. “This perverse burden shifting cannot coexist with the rule of law. In essence, the Court has now shoved lower court judges out of the way in cases where executive action is challenged, and has gifted the Executive with the prerogative of sometimes disregarding the law.”

Jackson added ominously, the ruling was an “existential threat to the rule of law”.

And that’s from one of the dissenting judges, not a columnist.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum