Comments

-

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of God

I'm sorry if it came across that way. But I was indirectly agreeing with your conclusion : "I think this is the best time to be alive". I even added a second PS, that may apply, if you get your bad news first hand. In my retirement gig, I now get to experience some of the "real world" in the urban ghettos of Chocolate City, as contrasted with Vanilla Suburb. Not to mention the napalming of Vietnam.You may not have intended it this way, but that comes across as both dismissive and irrelevant. — Tom Storm

But you seemed to imply that my somewhat positive worldview is based on Faith instead of Facts*1. Yet I rejected the "overarching narrative" of my childhood and constructed a philosophical worldview of my own from scratch. If I "wanted to believe" a fairy tale, my native religion had a happy ending to look forward to. But my current view does not predict anything for me, beyond this not-so-good-not-so-bad lifetime.

My personal worldview happens to agree with A.N. Whitehead about the Teleological trend in evolution. Which seems to align with your "best time" quote above. Yet, my "real world" has both Good & Bad features. But, like Anne Frank, I choose not to dwell on the downside. :smile:

*1. Excerpt from your post above : "Things may appear a certain way to us because we want to believe. We are sense-making creatures compelled to find or impose an overarching narrative on everything." -

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of God

FWIW, I'd suggest that you cut-back on your intake of Headline News. William Randall Hearst, magnate of the nation's largest media company, insightfully observed about the criteria for news publishing : "if it bleeds, it leads". Another version is "bad news sells". News outlets may have professional scruples about objectivity, but the bottom line says that the news industry is basically mass-market gossip and broadcast rumours. The function of Modern news networks is to collect information about "dysfunction and suffering: children with cancer, mass starvation, natural disasters, a clusterfuck of disease and disorder" from around the world, and funnel it into your eyes & ears.Well that's your conclusion, not mine.

If pushed, and speaking from a human perspective, you might say the world appears designed and calibrated for dysfunction and suffering: children with cancer, mass starvation, natural disasters, a clusterfuck of disease and disorder wherever you look. — Tom Storm

Even a high-tone philosophy forum like TPF, contributes its share of bad news in the form of criticism of sinful human nature and design flaws of Nature. But look around you with your own eyes & ears and make note of the last time you personally witnessed --- from your own "human perspective", not the media perspective --- "dysfunction and suffering: children with cancer, mass starvation, natural disasters, a clusterfuck of disease and disorder". You might even find some not-so-bad news on Good News Network, The Optimist Daily, and DailyGood. But these outlets are financially marginal because good news is boring. Our survival-scanning minds seem to be tuned to look for the exceptions to the common routine, because that's where threats are most likely to come from.

Our modern cultures are far safer from the ancient threats of tooth & claw, but now imperiled mostly by imaginary evils brought into your habitat by the Pandora's Box of high-tech news media. Maybe we all need a Pollyanna Umbrella defense-mechanism from pollution of the mind. :wink:

PS___ Catholics are taught from infancy about Original Sin. But my anti-catholic Protestant upbringing did not interpret the Bible from that inherently pessimistic perspective. We were taught about Free Choice, not Predestination for Hell. Did that blind me to Satan's schemes?

PPS___ If you live in Gaza or Ukraine, a bit of pessimism about man's inhumanity to man is justifiable. But, if you live in shopping center Suburbia, lighten-up! :joke:

"Pessimism leads to weakness, optimism to power." ___ William James : noted for promoting a philosophy of Pragmatism

"I don't think of all the misery, but of the beauty that still remains." ___ Anne Frank : died in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp

"The best and most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or even touched". ___ Helen Keller : deaf & blind from birth -

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of God

OK. But I interpreted "useless" to mean having no function or value. And "solace or salvation" seems to be the ultimate value for believers. So, the function of Faith is to get us to where our treasure is laid-up*1.↪Gnomon

I meant useful in the sense of offering solace or salvation. — Janus

However, if this world of moth & rust & thieves is all we have to look forward to, then investing in "pie-in-the-sky" heaven would be a "white elephant" of no practical value. :smile:

*1. Value & Treasure :

Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy and where thieves break in and steal, but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust destroys and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.

___ Matthew 6:19-21 -

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of God

Yes, but many people interpret the inherent randomness, indeterminacy, & uncertainty of quantum physics as a series of blundering accidents ; hence no divine intention or pre-destination. But there's another way to interpret the stochastic nature of Nature : it allows opportunities for novelty to emerge*1 from evolution, and the final outcome (the sum) is negotiable, un-decided until the the process is complete.A scientific account doesn’t describe life as an “accident” in any meaningful sense. It simply explains that life arose through natural processes. To call it an “accident” is to impose a value-laden metaphor onto a description that is, at its core, neutral. — Tom Storm

Evolution is not just a blindly meandering process*2, it's a progressive process. Not necessarily in the sense of Orthogenesis, but in terms of increasing complexity & novelty. The most obvious sign of creativity is the emergence of Life & Mind from a hypothetical primordial soup of meta-physical quarks & gluons. And the minds of those living creatures have introduced Purpose into the world. For some myth believers, their "higher" purpose is not just basic survival long enough to reproduce, but to thrive in a second chance at life.

Therefore, something is going on here that smacks of Teleology*3. That doesn't imply creation by divine fiat, for the purpose of producing sycophantic slaves of faith. But it does provide food for philosophical thought. A deterministic (cause & effect) universe would move quickly & directly to some predestined end : as in Genesis. Yet a lawful, but stochastic universe would erratically evolve by trial & error : Darwinian evolution*2. And the ultimate state of such a world would be unpredictable. So, purposeful people would have opportunities to pursue their own personal goals in their allotted lifetime. :smile:

*1.Emergence theory, in a nutshell, explains how complex systems can exhibit behaviors and properties that are not present in their individual components. It suggests that these emergent phenomena arise from the interactions and relationships between the parts, rather than being simply a result of their individual characteristics. Essentially, the "whole" is greater than the sum of its parts.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=emergence+theory

*2. While the statement "evolution is blind" is often used to describe the process of natural selection, it's not entirely accurate. While mutations are random, the selection process itself is guided by environmental pressures and the interactions of organisms with their environment. This means that evolution is not entirely blind but rather a complex process involving both random variation and directed selection.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=evolution+not+blind

*3. In Whitehead's philosophy, teleology, the idea of things having a purpose or end goal, is not about pre-ordained destiny, but about the dynamic and open-ended process of becoming. He viewed reality as a constant flux of actual entities (occasions of experience) that are continuously engaging with each other and co-creating new possibilities. This means that while there's a sense of ongoing creation and potential, there's no fixed endpoint or predetermined path for entities to follow.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=whitehead+teleology -

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of God

Perhaps, unless the deity is knowable by reason rather than revelation*1. That's what's called the "God of the Philosophers". For example, Spinoza imagined his God, not as transcendent, but immanent, serving as the very stuff of reality (substance ; being), which is otherwise inexplicable*2. And Whitehead describes his God as a "value creating process"*3. Which has evolved the human mind, as the only value-evaluating (usefulness) process in the world. :nerd:An unknowable divinity would seem to be useless to us — Janus

*1. Whether it is "being-itself" (Scholastics) or the "universal substance" (Spinoza), whether it is "beyond subjectivity and objectivity" (James) or the "identity of spirit and nature" (Schelling), whether it is "universe" (Schleiermacher) or "cosmic whole" (Hocking), whether it is "value creating process" (Whitehead) or "progressive integration" (Wieman), whether it is "absolute spirit" (Hegel) or "cosmic person" (Brightman)-each of these concepts is based on an immediate experience of something ultimate in value and being of which one can become intuitively aware.

___Excerpt from your Tillich passage

*2. The Big Bang theory assumed, axiomatically, that Energy & Regulations preexisted the bang. And from that cosmic Energy, all the matter in the world evolved. So, the God of Cosmology is essentially Cause & Laws.

*3. In Whitehead's philosophy, the process of creating value involves the "subject-superject" concept, where every event is both experiencing and aiming for a future state. This "subjective aim" drives the experience towards its ultimate satisfaction and realization, which is intrinsically valuable. Value, for Whitehead, is not an external attribute but rather the intrinsic reality of an event and its enjoyment.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=whitehead++value+creating+process -

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of God

Yes. Since I don't find the Judeo-Christian Bible or Islamic Koran plausible as the revealed word of God, I've been forced to create my own mythical story to establish the meaning of my own worthless life. It's intended to be a "middle ground", based on information & insights from Objective Science, Subjective Religions, and Rational Philosophy. My myth does not have a happy ending in transcendent Heaven, yet it does conclude that the evolution of Life & Mind from a mysterious Big Bang was not "accidental", but in some sense intentional*1. You could say that it's my own version of a "More Sophisticated, Philosophical Account of God". :smile:I think a lot of people share this intuition. I personally don’t and I don’t encounter any transcendent meaning in life or the universe as I understand it. What I do see is humans telling stories - stories that offer solace, meaning, and guidance for how to live.

To me, the idea that life is accidental or mindless isn’t necessary either. It doesn’t have to be a choice between God and Meaninglessness or theism versus nihilism. There’s perhaps a middle ground: a world where meaning is made, not given. — Tom Storm

*1. The idea that "life was not accidental" suggests that existence is not purely random or chaotic, but rather guided by a purpose or meaning, even if that purpose is not explicitly defined. This belief can be seen in various philosophical, religious, and personal contexts. . . .

The idea that "life is not accidental" can also be interpreted as a belief in the principle of cause and effect, where events are interconnected and influenced by preceding circumstances.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=life+was+not+accidental

Note --- Cause & Effect is not totally random or inconsequentially accidental, but reliably predictable. That's the assumption Science is based on. -

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of God

This post seems to highlight the various ways of "understanding" the world : a> Science, in terms of objective matter, and b> Theology, in terms of unknowable divinity, and c> Secular Philosophy, in terms of direct human experience. Science has a Blind Spot*1 in that it knows the world by means of Mind, but cannot know the subjective tool objectively. That limitation of objectivity may be why ancient Philosophy began to turn the rational microscope toward the viewer : a crude "selfie" so to speak*2. Later, Medieval Theology*3 began to use philosophical methods to look behind the Self, in order to know the Mind of God.The world as it appears to us is obviously understandable — Janus

Well, I don’t understand it, so there’s that. :razz: Logical fallacies aside, I suppose my intuition is that we understand some things. We’ve learned to make things work; we’ve developed remarkably effective models, tools, and narratives to account for what we observe. But does that amount to genuine understanding? — Tom Storm

But eventually, that attempt at double introspection became so effete that it's theories were comprehensible only by faith. So, the Enlightenment rebellion banned subjective Faith in favor of supposedly objective Empiricism. Yet, when hard evidence for mental phenomena (direct experience) proved unobtainable and indescribable in material terms, Modern Philosophy began to again use self-aware Reason to rationalize itself.

Unfortunately, as Hume noted, Reason can be the slave of the passions. Which is why Philosophical understanding requires a dispassionate perspective --- allowing mind to rise above body --- and a language based, as far as possible, on first principles instead of blind faith & selfish desires. Such self-knowledge & self-discipline may not amount to genuine or divine understanding, but it should make the material & mental world more understandable to our subjective experience. First know thyself, then put God under the microscope of reason. :smile:

*1. Blind Spot of Science :

But this image of science is deeply flawed. In our urge for knowledge and control, we’ve created avision of science as a series of discoveries about how reality is in itself, a God’s-eye view of nature.

Such an approach not only distorts the truth, but creates a false sense of distance between ourselves and the world. That divide arises from what we call the Blind Spot, which science itself cannot see. In the Blind Spot sits experience : the sheer presence and immediacy of lived perception

https://aeon.co/essays/the-blind-spot-of-science-is-the-neglect-of-lived-experience

*2. Plato's psychology, particularly his Theory of the Soul, explored the nature of the human mind and its relationship to the body. He proposed a tripartite model of the soul, dividing it into reason (logistikon), spirit (thymoeides), and appetite (epithymetikon), which represent different aspects of human nature and often conflict with each other. Plato believed that a harmonious society and individual life required reason to rule over spirit and appetite.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=plato+psychology

*3. Nick Spenser, theologian :

this essay, once it has done some necessary ‘explanation’, looks instead at one particular aspect of quantum theory, on which Ball touches frequently, and which I think is of real interest and relevance to theology: namely the business of using language to describe things that can’t really be described.

https://www.theosthinktank.co.uk/comment/2018/09/14/quantum-theology

-

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of God

Unlike Spinoza, Whitehead concluded that some Cause outside of our evolving spacetime Cosmos was necessary for a complete philosophical worldview. Surprisingly, he came to that conclusion before astronomers found evidence of an ex nihilo beginning to spacetime reality. Likewise, eons ago, Plato rationally inferred that a creation myth (Cosmos from Chaos) was necessary for his philosophical system, that ranked static*1 unchanging eternity above the dynamic ups & downs of mundane reality. Yet, all of these fleshless intellectual god-models may still not appeal to the non-philosophical mind.God is the fellow traveler and sufferer of the world. God is persuasive and not coercive. God offers possibilities for creative advance but does not force outcomes. God is the poet of the world.

I personally like Whiteheads conception but no linguistic or verbal description can adequately capture the God. — prothero

So, Whitehead may have felt that some human-like attributes (personhood) would make his god-model more acceptable : "fellow traveler", "sufferer" , "persuasive", "poet", etc. Although I agree that such personal features make the invisible intangible deity more accessible to the imagination, I still find it hard to picture his otherwise ghostly God as an allegorical father in heaven. In any case, an immanent participating deity feels better than a theological formless featureless apophatic*2 God that can only be described in terms of what it's not (e.g. Infinite : no spacetime definition). However, I don't take any of these metaphors literally.

Hard-core Materialists can't accept the notion of ex nihilo (something from nothing) world creation , so they envision a tower-of-turtles reality, where one evolving world stands on the back of another material world. But my worldview is based on causal Information, not malleable matter. So, I can accept Plato's notion of a formless, self-existent, ineffable, First Cause or omni-potential Chaos*1. That's closer to a mathematical concept than a material myth. :smile:

*1. What is the fundamental state of Statistics?

Statistics and spacetime, while seemingly disparate, have a surprisingly intricate relationship in modern physics. Statistics, in its core, deals with the probability distribution of data, while spacetime, as described by general relativity, is a dynamical, curved 4-dimensional structure where gravity is a manifestation of spacetime curvature. The intersection arises in the realm of quantum gravity and the statistical nature of spacetime itself, particularly in models involving quantum black holes.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=statistics+vs+spacetime

Note --- Most practicing statisticians think of their field only in terms of given data. But theoretically, the unspecified state of mathematical potential, containing all possible data, is necessarily infinite & unbounded. Plato's Chaos is essentially a Statistical black hole containing infinite possibilites.

*2. Apophatic theology :

Augustinian Negative theology, attempts to understand God by stating what He is not rather than what He is. It's a theological approach that acknowledges the limitations of human language and reason in fully grasping the divine nature. The point of apophatic theology is to move beyond conceptual understanding and towards a more mystical or intuitive experience of God, recognizing that true understanding is often found in what cannot be expressed.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=apophatic

Note --- As you said, "no linguistic or verbal description" can adequately define a transcendent God. -

The Forms

Like Plato & Kant, due to the Materialistic bias of our language, I have been forced to borrow or invent new words (neologisms) to describe Metaphysical*1 concepts that don't make sense in Physical terms. In my Enformationism thesis, I describe those "occult entities" as Virtual or Potential things. I'm appropriating terms that scientists use to describe not-yet-real particles and incomplete electrical circuits for use as metaphors of un-real Forms. At my advanced age, I am still learning the lingo.This does not mean that the forms are occult entities floating ‘somewhere else’ in ‘another world,’ a ‘Platonic heaven.’ It simply says that the intelligible identities which are the reality, the whatness, of things are not themselves physical things to be perceived by the senses, but must be grasped by reason. — Eric D Perl, Thinking Being, p28

So much of this has actually filtered through to the way we understand the world today - after all the Greek philosophers are foundational to Western culture. So to understand principles, to see why things are the way they are, is to see a 'higher reality' in the sense that it gives you a firmer grasp of reality than those who merely see particular circumstances. Indeed the scientific attitude is grounded in it, with the caveat that all of Plato's writings convey a qualitative dimension generally absent from post-Galilean science. — Wayfarer

The physical focus of ordinary language may be why Plato & Aristotle used allegories & metaphors to convey the idea of unseen things. That's also why Jesus spoke in parables about spiritual notions. Whereas Plato spoke of a "higher reality", I coined the term Ideality*2 to convey the same idea, without confusing it with mundane Reality. You could say, metaphorically, it's a parallel dimension of Qualia, yet it exists side-by-side with the phenomenal world as noumenal notions in rational minds. Unfortunately such abstruse language makes philosophy enigmatic for those who don't speak Jargon or Klingon. :smile:

*1. Meta-physics :

Physics refers to the things we perceive with the eye of the body. Meta-physics refers to the things we conceive with the eye of the mind. Meta-physics includes the properties, and qualities, and functions that make a thing what it is. Matter is just the clay from which a thing is made. Meta-physics is the design (form, purpose); physics is the product (shape, action). The act of creation brings an ideal design into actual existence. The design concept is the “formal” cause of the thing designed.

https://blog-glossary.enformationism.info/page14.html

*2. Ideality :

In Plato’s theory of Forms, he argues that non-physical forms (or ideas) represent the most accurate or perfect reality. Those Forms are not physical things, but merely definitions or recipes of possible things. What we call Reality consists of a few actualized potentials drawn from a realm of infinite possibilities.

#. Materialists deny the existence of such immaterial ideals, but recent developments in Quantum theory have forced them to accept the concept of “virtual” particles in a mathematical “field”, that are not real, but only potential, until their unreal state is collapsed into reality by a measurement or observation. To measure is to extract meaning into a mind. [Measure, from L. Mensura, to know; from mens-, mind]

#. Some modern idealists find that quantum scenario to be intriguingly similar to Plato’s notion that ideal Forms can be realized, i.e. meaning extracted, by knowing minds. For the purposes of this blog, “Ideality” refers to an indefinite pool of potential (equivalent to a quantum field), of which physical Reality is a small part. A traditional name for that infinite fertile field is G*D.

https://blog-glossary.enformationism.info/page11.html -

More Sophisticated, Philosophical Accounts of God

God-like powers without personhood*1 is what we call Nature, Universe, Cosmos . Traditional polytheistic notions of gods --- (Zeus {weather} ; Ceres {grain} ; Persephone {seasons} ; Bacchus {wine, orchards} --- gave unique personalities to sub-components of Nature-in-general. Viewed as the impersonal physical universe though, Nature doesn't do anything in particular, but everything in general. So, it's the specialized aspects of Nature that seem more personal and intentional : as when lightening strikes your house.Personally I find most philosophers’ conceptions of God are hollow shells that barely outline any type of entity; or they are anthropomorphic wishful thinking, slapping a face and personality on something that did not ask for it, like “being” or “the one” or “necessity”.

My sense is, if it’s a question of God, it is a question of personhood, — Fire Ologist

That may be why the image of a mercurial divine king on a heavenly throne makes more sense to common people than the timeless-spaceless-personless notion of strict Monotheism, and the abstract everything everywhere concept of Cosmos*2. But for rational philosophers, a broader non-specific definition may seem more plausible. That's why I think A.N. Whitehead's PanEnDeistic God may be an appropriate update of Plato's universal Cosmos*3. :smile:

*1. Five requirements for Personhood :

Next, “The Cognitive Criteria of Personhood” was created by Mary Anne Warren in 1973, where she lists the five requirements for a person to exist. The criteria includes consciousness, reasoning, self-motivated activity, ability to communicate and self-awareness.

https://www.focusonthefamily.com/pro-life/personhood-explained/

*2. Cosmos :

Ancient Greek: κόσμος, romanized: kósmos) is an alternative name for the universe or its nature or order. Usage of the word cosmos implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosmos

Note --- Plato described the creation of our world allegorically, as the emergence of a pocket of organized space-time-energy-law (cosmos) within a larger expanse of random-but-potential nothingness (chaos). This was a functional, instead of personal, kind of Creator. As a logic-worshiping philosopher, Plato may have preferred that simple rational abstract practical definition over the crazy quarrelsome pantheon of Greek gods.

*3. Whitehead's God :

Although he uses a theistic term for the creator of our evolving world, I think his concept of “God” is not religious, but philosophical. Whitehead’s associate Charles Hartshorne⁵ labeled his theology as : PanEnDeism⁶. This deity is not imagined on a throne judging the creation, but everywhere, including in the material world, participating in the on-going process of Creation.

https://bothandblog8.enformationism.info/page46.html -

The Forms

Thanks for that insight. I hope you'll pardon me for my layman's playful use of less technical terms for discussing "spooky" invisible concepts that are only apparent to highly intelligent beings. Although Principles are of primary importance for philosophers, they may be un-intelligible to non-philosophers. I suppose that all humans have some minimal ability to broadly categorize their environment, but only a few go so far as to break it down into fundamental (essential) concepts for understanding (intellectual comprehension). For example, most people can count up to ten, but only a few can deal with infinities & differentials.↪Gnomon

Plato’s so-called ‘Forms’ might be better understood as principles of intelligibility —not ghostly objects in another realm, but the structural grounds that make anything knowable or what it is. To know something is to grasp its principle, to see what makes it what it is.

And they’re neither objective - existing in the domain of objects - nor subjective - matters of personal predilection. That is why they manifest as universals — Wayfarer

We tend to broadly categorize obvious things, and their essential forms, into either Objective (material things) or Subjective (mental experiences). But, as you implied, Universals may be an overarching third class of knowables, and yet we only know them via rational extrapolation from objective observation. They are not obvious, but must be discovered (revealed) by means of rational work.

In my own profession, engineers view "structure" in terms of invisible force relationships (e.g. gravity, wind, earthquake), while laymen think of "structure" in terms of obvious beams, columns, and bricks. Engineer's design diagrams symbolize those unseen forces with vectors (arrows), which might be called "principles of intelligibility" or symbols (ideograms ; mind pictures) that stand-in for the physical flow of forces that our senses cannot detect directly. Likewise, the Form "Justice" is symbolized by a conventional word, that allows the mind to make invisible political inter-relationships intelligible. :smile:

In philosophical discussions, intelligibility refers to what the human mind can understand, contrasting with what can be perceived by the senses. Intelligible forms, according to ancient and medieval philosophers, are the abstract concepts used for understanding, such as genera and species, as opposed to concrete objects. The intelligible realm, as conceptualized by Plato, includes mathematics, forms, first principles, and logical deduction. Kant's work also explores the relationship between the sensible and intelligible realms, and the principles governing each.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=forms+principles+of+inteligibility -

The Forms

Yes. I'm sure you are not used to thinking of Forms in such irreverent terms. But my ignorant subjective/objective question about ideal Forms vs real Things, is "which is the caricature, and which is the original"? Did Plato discover the Forms, or did he invent them? It's just a rhetorical thought, no need to answer. :wink:Your depiction of the forms is something of a caricature. All I can say is, do more readings. — Wayfarer

PS___ Did Moses discover God's (formerly concealed) ideal laws on the mountain, or did he invent them? It's a question about authorship. :joke:

Plato's "Forms" are not discovered in the sense of being found by exploration. Instead, they are understood through a process of philosophical reasoning, particularly through dialectical reasoning (questioning and discussion). Plato believed that the Forms are eternal, unchanging, and the ultimate reality, and our understanding of them is a matter of recollection or intuitive grasp, not empirical discovery.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=plato+forms+discovered -

The Forms

What I'm still struggling with is the Subjective vs Objective nature of the Forms. Sure, Plato assures us that there is an ideal Concept, Pattern, Design of everything, but not in the Real world, so why should we believe him? As a professional designer myself, I like the idea that there is a perfect house for this couple, for example. But I've never even come close.While Moses's revelation is of eternal commandments, Plato's noetic apprehension of the Forms (especially the Form of the Good) is more intellectual ascent. — Wayfarer

Kant reasoned his way to the Categorical Imperative of morality, and others generalized the Golden Rule. But Plato implies that there is a perfect universal Form, on a shelf in the heavenly treasury, corresponding to every thing and every idea in our imperfect world*1. Carried to an extreme, presumably, there is a perfect Pickle, that is not subject to personal taste. Ideal Perfection is a nice idea, but is it true in any verifiable sense? Why should we "intellectually assent" to his noetic notion of The Good? Was Good/God a poor designer, or is there a good reason for the sorry state of our local world, after 14B years of development?

I suppose the reason I'm quibbling is because an atheist or materialist would deny that anything is perfect in our randomized accidental world. Karl Marx wanted to make the material world better, but did he envision a perfect Utopia? Why is perfection always unattainable? Why is Reality so screwed up? Why did God/Good create an inferior world of shoddy things, and keep the quality stuff for himself in Form Heaven? I'm talking like an a-form-ist here, so I can learn to answer such skeptical questions.

Back to Objectivity, would any two people agree on what constitutes an Ideal Dog? Or an ideal God? :wink:

*1. The Forms are not limited to geometry. According to Plato, for any conceivable thing or property there is a corresponding Form, a perfect example of that thing or property. The list is almost inexhaustible. Tree, House, Mountain, Man, Woman, Ship, Cloud, Horse, Dog, Table and Chair, would all be examples of putatively independently-existing abstract perfect Ideas.

https://philosophynow.org/issues/90/Plato_A_Theory_of_Forms

*2. Moral & Mathematical Forms :

"So I believe that morality is something that's discovered, in the same manner that pure mathematics discovers universal truth : it's not within us but out there."

Philosophy Now magazine p64 (April 2025) -

The Forms

Ha! I didn't mean to equate them as "historical types", such as a messianic prophet. I imagined them as more like analogous divine intermediary types, handing down the Truth of God (Laws vs Forms) to ordinary mortals.Many would say that Plato and Moses were completely different historical types — Wayfarer

I was just using Moses as an example of a system-maker whose supposedly divine rules were accepted on the basis of his designated authority as an interpreter of divine intentions. A more modern formal system is the notion of Natural Law that is based on the authority of secular Science, not any particular person. Hence, the ultimate authority is Nature (ultimate Reality ; Pantheos) itself, and scientists are merely self-designated interpreters. Moses' system of Divine Laws was built upon the ultimate authority of God (Ideality), and Moses was simply his messenger. Likewise, Plato's system of eternal Forms was also supposed to reveal True Reality (Ideality) that was unknown by ordinary people. So the ultimate author of those Forms was not Plato, but Nature, or God, or Good*1.

Anyway, it looks like I'm forced to answer my own poorly-formed amateur philosopher query : "My question is this : did Plato ever imply that his ethical rules (Forms) had something like divine authority?" Apparently, the answer is a provisional Yes : Plato wrote the books, but implied that the ultimate author is the essential principle of Perfect Good, and Plato is his messenger*2. Just as the Demiurge is the PanEnDeistic builder (enforcer) of our imperfect world, not of Forms, but of Things. Is that a plausible comparison of religious/philosophical system-builder, acting as intermediary for the ultimate law-maker?

Autocratic human rulers have always been aware that subjective rules are hard to enforce in a mob of independent thinkers. So, most societies & civilizations, until recently, have officially claimed that their laws are actually objective, and ideally universal, instituted not by the human on the national throne, but by the supreme God on a heavenly cathedra. Even modern secular societies may play lip service to something like Kant's Categorical Imperative : an objective universal principle that applies to all people everywhere all the time.

Perhaps Plato's perfect Forms were a similar attempt to overrule the varying opinions of quibbling quarreling philosophers with a "buck stops here" set of divine opinions, defined as perfect, unchanging, eternal verities. Surely, an ideal god-mind wouldn't create a not-yet-perfect, evolving, space-time world of relative truths and real things. Hence, the necessity for a subordinate (Demiurge) to blame for screwing-up God's divine plans. 2500 years later many of us still revere Plato as the revealer of the formal structure of the good-God's more perfect realm, for us mortals to strive for and fail. Or did he just make it all up from bits of previous philosophical systems, sans revelation? :smile:

PS___ This rambling notion, of how Ideal Forms were disclosed to humans as a supernatural system, still seems garbled, so I'll blame its imperfections on the semi-divine Demiurge we call material Evolution.

*1. In Plato's philosophy, the term "God" can be understood in a few different ways. Plato believed in a single, transcendent, and all-good being, which he often referred to as the Form of the Good. He also acknowledged the existence of other, lesser gods, often associated with the Greek pantheon, and saw them as divine beings, but not on the same level as the ultimate source of all good. Plato's concept of God also involves a Demiurge, a divine artisan who shaped the universe according to the Forms.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=plato%27s+god

*2. Islamic Shahada : "There is no God but God, and Muhammed is his messenger"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shahada -

The Forms

Philosophy Now magazine (April 2025) presents the Question of the Month : Is Morality Objective or Subjective? And one writer said "Objective moral principles are necessary to reconcile worldviews". So, it occurred to me that his theory of universal Forms might have been an attempt to objectify-by-edict ("thus saith the Lord") mandatory ethical rules that would otherwise be endlessly debatable.So does the distrust of Platonism really come down to the fact that Plato's 'ideas' are not things that exist in space and time, and that the only reality they could possess are conceptual? — Wayfarer

Yet, those imaginary abstract Forms out there in the intangible-yet-rational Aether are obviously not Empirically real. So it seems we must accept them on Plato's authority, or by agreement of our own reasoning with his. Similarly, the ancient Hebrews were presented by Moses with a compendium of ethical rules, that were supposed to be accepted as divine Laws. And violations would be punishable by real-world experiences, up to and including death & genocide. However, rather than using direct lightening bolts to punish transgressors, Yahweh used the communal belief system of his chosen people to do the job. Moses, like Plato, may have gotten his rules & principles via subjective reasoning (and historical precedent), not by divine revelation. But did P expect people to take them on faith?

Plato's Ethics*1 were based on certain moral virtues (principles) that may qualify as universal Forms. But some of Moses' Commandments, such as "Thou Shalt Not Kill" were in need of nuance. So Plato kept his Virtues general enough to apply to various situations : by interpretation from general to specific. My question is this : did Plato ever imply that his ethical rules (Forms) had something like divine authority*2 and real world enforcement? If not, then we would expect practical Morality to be subjective & disputatious, and oft-broken in deed and in principle. :smile:

*1. In Plato's ethical theory, moral virtues like justice, courage, and wisdom are considered Forms, representing the ideal and unchanging essence of these qualities. Plato believed that moral actions and character are guided by a higher realm of perfect Forms, with the Form of the Good at the apex, influencing the existence and intelligibility of all other Forms, including those of morality.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=plato+morality+forms

*2. Plato believed that forms are divine. Their connection to divinity is what makes forms perfect: they lack the flaws of humans and of the physical realm. They are of a higher order of existence than their physical representations.

https://study.com/learn/lesson/plato-theory-forms-realm-physical.html

Note --- Natural "Laws" (Principles), like Gravity, can be learned by experience, and violations are immediately punished by the physical system of cause & effect. But some of the long-term evolutionary processes, such as Ecology, may take generations to see the objective results. Scientists attempt to see (infer) future states, by application of rationally-acquired general logical & mathematical rules. Perhaps Natural Morality requires more logical insight than the average person possesses. So, maybe we still need those divine edicts. -

The Forms

Yes. And the Quantum physics of early 20th century seems to have required a Philosophical return to Platonic logistikon*1 (reasoning ability) after years of reliance on technological mēkhanikos*2. When subatomic particles proved to be too small for their devices to resolve, scientists were forced to resort to statistical math*3 to determine the structure & properties of unseen things. Thus, modern Physics became more Theoretical, and less Empirical. For example, Einstein & Planck didn't work in gadget-filled laboratories, but in pencil & chalk provisioned offices.The concept of Forms in Plato is not about invisible particles or mathematical abstractions per se, but about the intellect’s ability to grasp stable, intelligible principles that underlie the flux of experience. — Wayfarer

Ironically, the "seat" of Reason is sometimes referred to as a "part" of the immaterial soul, instead of a specialized function (ability) of the body/brain. I suppose thinking of Logic/Reason as-if a plug-in component is easier than imagining a non-local ghostly Form that mysteriously "grasps" other "intelligible principles".

Even more thought-provoking is the notion that fundamental particles, such as the Higgs Boson*4, are defined as local disturbances in a non-local Field of statistical potential. Underneath its invisibility cloak, the boson masquerades as inertial Mass, which is a mathematical property, not a particular thing. You could say that it is the "intelligible principle" of Gravity. Apparently, Plato took that formal essence of weightiness for granted, without comment. :smile:

*1. The logistikon is the part of the soul that deals with logic, thought, and learning.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=logistikon

*2. As particles get smaller machines get larger :

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is considered the largest machine ever built. It's a massive particle accelerator located at CERN near Geneva, Switzerland. The LHC consists of a 27 km circular tunnel where beams of protons are accelerated to near light speed and then collided to study fundamental particles.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=biggest+machine+on+earth

*3. "Subatomic math" refers to the calculations and concepts used to understand the structure and properties of atoms and their constituent particles. It involves understanding the number of protons, neutrons, and electrons in an atom, as well as the relationship between atomic number, mass number, and atomic mass.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=subatomic+math

*4. God Particle :

The Higgs boson, sometimes called the Higgs particle, is an elementary particle in the Standard Model of particle physics produced by the quantum excitation of the Higgs field, one of the fields in particle physics theory. ___Wikipedia

Note --- Excitation is an exchange of Energy, which is causal potential, not material particle. But where does this mysterious incitement to Gravity come from? -

The Forms

In quantum physics today, the "smallest units of matter" (e.g. quarks, preons) are statistical probabilities rather than physical objects. Yet, the units of Statistics are data : bits of Information. And the four main types of statistical data are nominal, ordinal, discrete, and continuous. All of which are categories of mental concepts, not instances of material objects*1.I think that on this point modern physics has definitely decided for Plato. For the smallest units of matter are, in fact, not physical objects in the ordinary sense of the word; they are forms, structures or — in Plato's sense — Ideas, which can be unambiguously spoken of only in the language of mathematics.

The philosophical worldview of Atomism seems to imply that the material world is infinitely divisible into smaller components. The current title-holder of minimal matter is the hypothetical particle labeled Preon*2. Yet, they are only known to exist in the minds of theoreticians as mathematical definitions. Would Plato accept Preon in his realm of ideal Forms?

Since the foundations of modern Quantum Physics are more statistical than empirical, their primary tool today is Mathematics. Yet, practitioners seem to imagine their subject matter as Material (particles) instead of Mathematical (ratios, relationships). However, some theoretical mathematicians may admit to being Platonic Idealists*3. Which is more a matter of Faith : Materialism or Platonism? :smile:

*1. Yes, generally speaking, mathematics is considered a mental process rather than a physical one. Math deals with abstract concepts, numbers, and relationships that exist within the mind, rather than being physically tangible. While we might use physical tools like paper, pencils, or calculators to aid in calculations, the underlying mathematical principles are mental constructs.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=math+is+mental+not+physical

*2. Preon models are theoretical frameworks that propose that quarks and leptons are themselves composed of smaller, more fundamental particles called preons.

Preon models arose from the desire to find a simpler, more fundamental level of building blocks, akin to the periodic table for atoms, and to address certain theoretical inconsistencies within the Standard Model.

While preon models attempt to explain certain aspects of particle physics, they lack experimental confirmation and are considered speculative.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=evidence+for+preons

*3. Yes, in a philosophical sense, mathematicians are often described as idealists, particularly within the context of mathematical platonism. This view suggests that mathematical objects, like numbers and geometric shapes, exist independently of our minds and are part of a realm of ideal objects.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=mathematicians+are+idealists -

The Forms

I agree. The ancient Greeks didn't have the technology to dissect real material things into their substantial elements (e.g. Atoms). So instead, they tried to analyze Reality into the Ideal/Mathematical essences of the world (e.g. Forms). We now call that "pursuit" of abstraction Philosophy. Over time though, technological inventions, such as the telescope and microscope, allowed Natural investigators to actually see what before could only be envisioned via Mathematics and imagined by Reason.In this way, it is the pursuit of the ideal that allows us to calculate the behavior of objects in motion sufficiently enough to visit other bodies in space. In my view, by doing so humanity clearly demonstrated that the ideal was real. — David Hubbs

However, I still like to maintain the distinction between scientifically Real (material, physical) and philosophically Ideal (mathematical, logical). Otherwise, our forum communication would become confusing. So, I would say that Philosophy has demonstrated that visible tangible material Reality, is fundamentally invisible essential logical Ideality. Plato's Logos & Forms were early allegories (parables?) for understanding essential unseen structures & causes of Matter & Mind. But Materialists tend to interpret those abstract metaphors literally*1.

Some modern philosophers, perhaps envying the practical successes of Physical Science, tend to interpret the world in terms of sensable/material objects (Things), instead of logical/mathematical concepts (Forms). Therefore, we need to be careful to define what Real means to each party. :smile:

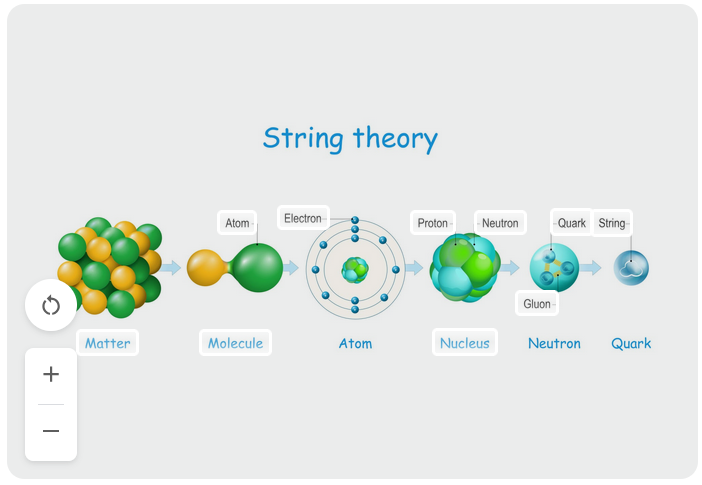

*1. For example, Quarks & Strings --- as illustrated in the String Theory image above --- that can only be defined mathematically, are still imagined as geometrical lines & spheres of matter, not mind. -

Which is the bigger threat: Nominalism or Realism?

Those who hope for salvation in an Ideal ghost-populated harp-strumming Heaven, might view worldly Realism*1 as a threat to their faith. And secular philosophers, who imagine that Plato's realm of Ideals & Forms is a remote-but-actual parallel word, might view Nominalism*2 as a threat to their worldview. Personally, I don't fit either of those categorical -isms, so I don't feel jeopardized by either belief system.I'm hoping someone can point me in the direction of those who see realism as a threat, and we can continue this ancient battle on an even footing. — NOS4A2

Someone in this thread mentioned Practical Idealism*3, so I Googled it. For me that BothAnd attitude seems to combine the best of both Pragmatic and Idealistic philosophies. That way, you are safe from faith threats from any direction. :smile:

PS___ I don't know anything about Pierce's Objective Idealism*5, but it also seems to cover both bases. Hence, may offend both Nominalists and Idealists.

*1. Realism and nominalism are opposing philosophical positions primarily concerned with the problem of universals. Realists believe that universals (abstract concepts like "redness" or "justice") are real and exist independently of our minds, while nominalists argue that universals are merely names or concepts created by the mind to classify particulars (individual objects)

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=realism+vs+nominalism

Note --- Universals are presumed to exist in a universal Mind (God). They exist in human minds only as Names referring to a General Concept. In this context though, Realists are faithful Idealists. This name-game makes my head spin.

*2. Idealism and nominalism are contrasting philosophical perspectives that offer different explanations for the nature of reality. Idealism proposes that reality is fundamentally mental, while nominalism asserts that only individuals and particulars exist, with universals being mere names or concepts.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=idealism+vs+nominalism

Note --- The universe does not seem to be "fundamentally mental", since minds only emerged after billions of years of physical development. And yet, the original Cause of the Cosmos must have included the Potential for eventual mental noumena. But Potential is not-yet Real. So is it Ideal, or something else?

*3. Practical idealism is a philosophy that emphasizes the importance of both having high ideals and being pragmatic in pursuing them.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=practical+idealism

Note --- Pragmatism/Realism and Rational Idealism are not necessarily in opposition, unless you choose to view them that way. They can be philosophically reconciled from a Holistic perspective. See *4

*4. Both/And Principle :

My coinage for the holistic principle of Complementarity, as illustrated in the Yin/Yang symbol. Opposing or contrasting concepts are always part of a greater whole. Conflicts between parts can be reconciled or harmonized by putting them into the context of a whole system.

https://blog-glossary.enformationism.info/page10.html

Note --- The "Greater Whole" is the organic Cosmos, including both Matter & Mind. Some philosophers idealize the Cosmos as an omnipotential unknowable transcendent deity, as in PanEnDeism

*5. Charles Peirce The philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce defined his own version of objective idealism as follows: The one intelligible theory of the universe is that of objective idealism, that matter is effete mind, inveterate habits becoming physical laws.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Objective_idealism

Note --- That sounds like a pragmatic/semiotic version of PanEnDeism. Physical laws embodied in matter take the place of commandments engraved on stone. -

Positivism in Philosophy

Even though Positivism & Empiricism, postulated as-if universal principles, fail their own test, they still serve as good rules of thumb for Scientific investigations into the material world. But, when Philosophical theories & principles are judged by that pragmatic criteria, they miss the the point of philosophizing : to go beyond the limits of the senses using Logical inference, not mechanical magnification. :smile:A basic criticism of positivism, particularly logical positivism and its central Verification Principle, is that the principle itself fails to meet its own criterion for meaningfulness. — Wayfarer

The Point of Process Philosophy :

I can't say with any authority, what Whitehead's "point" was. But my takeaway is that he was inspired by the counterintuitive-yet-provable "facts" of the New Physics of the 20th century ─ that contrasted with 17th century Classical Physics ─ to return the distracted philosophical focus :

a> from what is observed (matter), to the observer (mind), b> from local to universal, c> from mechanical steps to ultimate goals.

Where Science studies percepts (specifics ; local ; particles), the New Philosophy will investigate concepts (generals ; universals ; processes). The "point" of that re-directed attention was the same as always though : basic understanding of Nature, Reality, Knowledge, and Value.

https://bothandblog8.enformationism.info/page44.html -

The Forms

Ironically, although Strings are defined as vanishingly small --- smaller than sub-atomic particles --- they are still assumed to be material & physical, not just mathematical. The image below indicates that some physicists imagine Strings as physical things : building blocks of Quarks, which themselves present no physical evidence to support their theoretical existence.I believe that string theory is closest one can approach the Forms in terms of mathematics and physics as one would or could imagine. It's the only field in physics that is entirely dependent on mathematical relations. — Shawn

However, for all practical purposes, String Theory has been criticized as merely a plaything for extreme math aficionados. So in that sense, the String Theory may qualify for the same criticisms of Plato's hypothetical Forms : they're not Real. :smile:

PS___ Since all they do is vibrate, I would equate the mathematical strings with pure matterless Energy.

-

The Forms

Yes. Plato used the formal structure of geometry (e.g. triangles) to describe the Truth & Utility of immaterial Ideas relative to material Objects*1. Likewise, modern quantum physics deals with the invisible structure of matter that can only be known by means of mathematics*2. Hence, we accept the statistical wave nature of subatomic "particles" as True, even though they don't behave like ordinary matter (e.g. quantum tunneling ; two-slit experiment).1. The Forms are a separate domain of discourse, which one is only able to grasp with understanding of mathematics. — Shawn

So, Quantum Physics is a "separate domain of discourse", apart from Newtonian Physics of ordinary experience. But quantum truths are useful as tools for manipulating macro matter, only by means of Newtonian mechanics. So notional Forms & material Things work together to make a livable Real World for human animals.

Some relevant domain distinctions are Abstract vs Concrete & Relations vs Things & Ideal vs Real & Mental vs Material & Cultural vs Natural. The Forms, like Math, are logically true even though materially false. In their relevant cultural domain (psychology ; philosophy), Forms are useful tools for thinking, even though useless for manipulating matter, until trans-formed into a natural domain (physics ; science). :smile:

*1. Math is Form :

Yes, that's a key aspect of mathematics. It's considered a formal science because it deals with abstract structures and relationships, rather than directly with physical objects or the natural world. Mathematical statements are not about tangible objects, but rather about the relationships within formal systems

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=mathematics+is+formal+not+physical

*2. Quantum Math :

Because many of the concepts of quantum physics are difficult if not impossible for us to visualize, mathematics is essential to the field. Equations are used to describe or help predict quantum objects and phenomena in ways that are more exact than what our imaginations can conjure.

https://scienceexchange.caltech.edu/topics/quantum-science-explained/quantum-physics -

The Forms

Since I'm an old fogy, defining Essences in the infinite (undefinable) context of zillions of possible (not yet real) worlds just hyperbolically complicates the concept for me. Why not just define Forms in terms of concepts, patterns & meanings (Essences) in human minds, in the only uni-verse (one world) we know anything about? {i.e. parsimony} Wouldn't plain old Aristotelian Logic suffice to deal with that narrow definition*1?There is a clear way of talking about essences, as those properties had by an object in every possible world in which it exists. We can deal with the consequences of essences using this stipulation. — Banno

As I understand it, Plato's allegory of a perfect heavenly realm of ideal Forms was not one of a zillion worlds, but merely a metaphorical comparison to the only world from which we extract Mental images from Material sensations. Aristotle brought the notion of Forms back down to Earth in his theory of Hylomorphism*2 : a combination of Ideal & Real (mind & body). And the informed ideas are those of homo sapiens on planet Earth, not on fantasy planet X007-Stellaris in a parallel world far far away.

Personally, I still don't see any need for logical complications to understand the meaning & application of Essence*3. The philosophy of Materialism seems to have been formulated*4 specifically to deny the existence of immaterial Forms & Ideas & Meanings & Metaphors & especially Souls. But, doesn't that also deny all the features (e.g. abstract reasoning) that distinguish humans from animals? :smile:

PS___ If we actually had examples from each of those hypothetical possible worlds, the preponderance of evidence would get us closer to absolute Truth. Sadly we only have one sample world to study.

*1. In philosophical discussions, "forms" and "essences" are often used interchangeably, representing the fundamental nature or defining characteristics of a thing. Specifically, "forms" are the abstract, ideal, and unchanging essences of things, while physical objects are mere imitations or participants in these forms.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=form+and+essence

*2. While Aristotle also recognized the importance of form, he saw it as residing within things themselves, not as a separate realm. For Aristotle, form and matter are inseparable aspects of a thing, and the form gives the matter its specific characteristics.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=forms+are+essences

*3. Essences :

This term refers to the fundamental nature or defining characteristics of a thing, which gives it its identity. In other words, the essence of a thing is what it is, what it cannot be without losing its identity.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=forms+are+essences

Note --- Where is the material substance in these examples?:

# The essence of love is unselfishness.

# The essence of capitalism is competition.

# The essence of justice is fairness.

*4. To Form-ulate :

To express (an idea) in a concise or systematic way. ___Oxford dictionary

Note --- in other words, to Formulate means to use words to convey the imaginary idea of the identifying characteristics that are abstractions from what can be known via the physical senses. In this case, the imaginary idea is that Matter is the Essence of everything in all possible worlds.

-

The Forms

Due to my academic laziness, has decided not to take me on as an apprentice in the monk-like vocation of Modal Logic. Which is fine by me, since he never explained what it has to do with the topic of this thread. I am somewhat interested in understanding Plato's Forms in a modern context. But as a retired philosophical dabbler, not a full-time professional scholar, I don't have the time or need or interest to invest in a "more formalized system of reasoning"*1.Because it is—or was—embodied in a living philosophy, not merely in the textbooks of scholars. And indeed, the origin of those schools of thought does trace back to the Platonist tradition (in the broad sense), but philosophy as a way of life, not just an academic pursuit. — Wayfarer

Since you have a much broader & deeper knowledge of Philosophy-in-general than me, can you sketch-out --- informally --- what "formalized" Modal Logic has to do with Platonic Forms*2? The Google overview doesn't indicate much overlap between those fields of study. The only commonality that I see is in understanding Probability, Possibility & Potential. But I get the impression that Banno thinks this more refined logic would undermine Plato's (unreal) idealistic reasoning. Do you think Modal Logic would shed light on the relation between Plato's "ultimate reality" (which I call Ideality) and the manifold modes/moods of propositional calculus, or the rationalized categories of mundane reality? In other words : are the Forms simply esoteric BS? :smile:

PS___ Did Plato imagine his realm of perfect Forms literally as the heavenly True Reality, or the best one of many possible worlds? If so, then Modal Logic might establish the odds of such a world being real. But Nominalism might label Form-World as a name without referent. Yet I never thought of Ideality in those terms. Instead, it was more like an as-if metaphor, or a thought experiment, or mythical allegory. Not to be taken literally.

*1. Aristotle is often considered a pioneer of modal logic, exploring concepts of necessity and possibility. However, modern modal logic differs significantly in its formalization, scope, and application of these concepts. While Aristotle laid the groundwork, modern modal logic expands on these ideas to encompass a broader range of modalities and provides a more formalized system for reasoning. . . . . Modern modal logic is highly formalized and axiomatized, while Aristotle's approach was more descriptive and focused on specific syllogistic structures

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=modal+logic+vs+aristotle

*2. Modal logic and Plato's Theory of Forms are distinct philosophical concepts. Modal logic is a branch of logic that deals with concepts like possibility, necessity, and other modalities, allowing for the analysis of statements that are true under certain conditions or could be otherwise. Plato's Theory of Forms, on the other hand, is a metaphysical and epistemological theory that posits the existence of abstract, perfect, and unchanging "Forms" as the ultimate reality, with the physical world being merely a shadow or imperfect copy of these Forms. While both deal with abstract concepts, they differ significantly in their focus and application.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=modal+logic+vs+platonic+forms -

The Forms

Wayfarer doesn't seem to be offended by my skeptical questions & confused responses, or postulated alternatives. Maybe his pedagogical posts are flexible and open to interpretation, not take it or leave it. However, I do sometimes read a big “sigh” between the lines, when I just don't get it.↪Gnomon

You've made your mind up about modal logic, before you understood it. As a result you are "unavailable for learning".

]Not much point in my continuing in an attempt to to teach you, then. — Banno

It's true that I'm "unavailable for learning" by means of the old unscrew-the-top-of-the-head-and-pour-it-in technique. I learn best by trial & error, and question & answer, and self-teaching methods. Besides, a topic that seems absurd on the face of it does not invite enthusiasm for learning. That's why I asked Wayfarer repeatedly to explain the strange notion of "Degrees of Reality". But he tolerantly offered different ways to interpret that phrase. I still don't get-it, but I appreciate his pedagogical patience. :smile: -

The Forms

Sorry for nit-picking. But "might have been" is a retrospective acknowledgement that the Possible world (mode of being) did not, in fact, become an actual world ; hence remains an ontological non-existent no-when non-entity : an immaterial idea. So, we are back to an abstract timeless imaginary scenario.The qualification "might have been" seems to imply that the imaginary "things" did not come to be (to exist), hence not ontologically real — Gnomon

Not always. The might come to pass. They do this when the possible world is the actual world. — Banno

As I said before, "Like Multiverse and Many Worlds models of abstractly logical possibilities, his Modal Reality does not seem to be in danger of empirical falsification or actual contradiction". So, his Modes are no more realistic than Plato's timeless matterless Forms. It's neither True nor False, but merely an exercise in logical reasoning, from which we may learn some philosophical principles (tools for thinking). You can choose which universal proposition best fits your own belief system. :smile: -

The Forms

Thanks for the Stairway to Heaven overview. However, I still find the term "degrees of Reality" hard to fathom. It seems to imply that each Stage of Spirituality is a different Reality*1 : subjective state of existence? But, at my advanced age, I can look back and see (imagine) multiple stages of Intellectual (spiritual?) development. But the various phases seem to occur within the same single over-arching Reality : objective sum of all that exists.Each level includes but transcends the previous—forming a natural hierarchy where higher beings realise a greater degree of actuality and potentiality. — Wayfarer

Philosophically, I can interpret the mystical logic of the Great Nest of Being chart, as a hypothetical diagram of Spiritual evolution from statistical Potential (divine intention??) to inert Matter, to living Organisms, on up to human Psychology, and ultimately to the Samma-sambodhi state of Enlightenment. In which case, I am stuck on one of the middle rungs of spirituality ; still encumbered by a material body & Western mind.

Perhaps though, from a scientific perspective, the "natural hierarchy" could also be viewed as degrees of systematic development : Darwinian Evolution. Still, our extant Reality --- our 14B year old propagating world --- could be described as a "greater degree of actuality and potentiality". For example, the pre-Bang Singularity (a hypothetical mathematical entity) had little Actual stuff, but Cosmic-scale Potential. So, in retrospect, we now observe a hierarchy of developmental stages, from Math to Matter to Mind to Spirit???

I suppose I'm just showing my ignorance of Eastern philosophy, and my reliance on Western science for understanding how my world came to be what it is : a complex amalgam of Stuff & Sense & Sentience. Which we analyze into a logical progression of emergence. :smile:

*1. In philosophy, "reality" refers to the actual state of things, existing independently of any specific observer or perception. It's the fundamental nature of existence, encompassing all that is not imagined or theoretical. Philosophers explore different perspectives on reality, including realism, idealism, and materialism, each with its own view of what constitutes real existence.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=reality+philosophy -

The Forms

Sorry to come back to this mind-warping concept, spinning off from Plato's spooky Forms. But how does the notion of "degrees of reality" differ from the "stipulated models" & "possible worlds" in Banno's post*1 to tim wood? Also how does Lewis' notion of Possible Worlds as "real concrete places"*2 compare to "degrees of reality"? Are they the same "possible worlds" that populate the MWI model*3 of pop-up Possible universes created by quantum measurements? Are they all Real to the same degree?As I’ve mentioned several times in this thread and elsewhere, this depends on the understanding that there are degrees of reality (or realness? — Wayfarer

I'm just expressing my layman befuddlement. So, I won't mind if you choose not to address these mind-muddling infinities and hierarchical realities, in the forum format. Are the thinkers who explore such meta-physical "logical possibilities" trying to out-metaphor Plato's Cave, or to water-down the notion of a Real Heaven with infinite Realities? Is our own 21st century Possible Reality a recapitulation of the rational excesses of medieval Scholasticism*4? :chin:

PS___ Metaphysical reasoning does not play by the same rules as Physical reality. So, it seems that anything logical is Possible, and almost impossible to contradict.

*1.

Note --- The qualification "might have been" seems to imply that the imaginary "things" did not come to be (to exist), hence not ontologically real . . . . at least in our little corner of the Multiverse. :cool:They are just stipulated models of how things might have been. So I might not have written this post - that can be modelled as that there is a possible world in which I didn't write this post. It's that simple. — Banno

*2. David Lewis, a prominent philosopher, is best known for his modal realism, which posits that all possible worlds are real, concrete entities that exist in the same way as the actual world. He argues that these possible worlds are not mere abstract ideas or thought experiments, but rather they are real, concrete places just like our own.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=david+lewis+possible+worlds

Note --- Like Multiverse and Many Worlds models of abstractly logical possibilities, his Modal Reality does not seem to be in danger of empirical falsification or actual contradiction. Unless, of course, I meet myself crossing-over from a parallel universe. :joke:

*3. The Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI), also known as the many-worlds theory, suggests that every quantum measurement causes the universe to split into multiple parallel universes, each representing a different possible outcome of the measurement. In other words, rather than a single outcome being determined, all possible outcomes exist in their own separate universes.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=many+worlds+theory

*4. Scholasticism, while influential, faced criticism for its perceived excesses, particularly its focus on abstract reasoning and detailed argumentation at the expense of practical application and genuine moral and ethical concerns. Critics, including humanists, pointed to a tendency to prioritize legal, logical, and rationalistic issues, potentially overshadowing more profound ethical questions

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=excesses+of+scholasticism -

Which is the bigger threat: Nominalism or Realism?

From my brief exposure to the concept of Nominalism, I get the impression that it is often used as a slur. For example, "Liberal" is generally non-threatening, while "Radical" implies a destructive intent. But Trump tweets tend to equate the terms. Likewise, "Abstractionism" merely distinguishes mental representations from the objective referent, while "Nominalism" is interpreted as denial of Truth, Beauty & Goodness. In the first sense, I may be a Nominalist, but in the second sense, I am definitely not a denier of Universal concepts. So, what was Pierce going-on about? :smile:Nominalism rejects the existence of universals and abstract entities and other artificial creations, or any combination of the above. — NOS4A2 -

The Forms

I wasn't familiar with the notion of "degrees of reality", so I Googled it*1. I had always assumed only two degrees : Real or Ideal, Actual or Possible. Multiple in-between degrees seems overly complicated ; like Many Worlds models of reality. What do we gain by sub-dividing Reality into multi-level hierarchies? Doesn't that notion make pragmatic Scientific work into guesswork? It certainly confuses me. Maybe this neither-here-nor-there (watered-down reality) interpretation of Plato is what causes to exasperate "Meh!". Does my stubborn two-degree worldview mean that "I'll only consider stuff that reinforces the views I already have"? :smile:As I’ve mentioned several times in this thread and elsewhere, this depends on the understanding that there are degrees of reality (or realness?) — Wayfarer

PS___ Banno's two-value worldview seems to be : it's either Real or Wrong.

*1. Plato's theory of Forms posits that there's a hierarchy of reality, with the most real entities being the Forms (like the concept of "justice" or "beauty"), while physical objects and particulars are seen as imperfect copies or representations of these Forms. Plato suggests that physical objects have a "half existent, half non-existent" state compared to the Forms, indicating a lower degree of reality.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=degrees+of+reality

One common interpretation of Plato seems to be that Forms exist as abstract ideas in the Mind of God*2, not as surreal things or ghostly shapes in a Platonic Heavenly place. This metaphor of a two level hierarchy is easier for me to understand : it's either Real (objective ; physical) or Ideal (subjective ; metaphysical). Am I missing something important in-between those philosophical categories? :smile:But in the examples you’ve given, I already see the kinds of mistakes that I think have crept in to the interpretations of Plato through centuries of interpretation. Chief amongst them is the idea that the ‘forms’ exist in some ‘ethereal realm’, a ‘Platonic heaven’ which is ‘separate’ from the ‘real world’, and also that ‘form’ can be understood as an ideal shape, which I think is completely mistaken. — Wayfarer

*2. Plato's concept of the Forms, or Ideas, is not directly equated with God in the traditional Christian sense, but they are often interpreted as reflections of God's mind. In Plato's philosophy, the Forms represent perfect and eternal archetypes of things, existing outside of the physical world. The Form of the Good is considered the highest Form, and some interpretations see this as analogous to the Christian understanding of God. Christian thinkers like St. Augustine interpreted the Platonic Forms as God's ideas, suggesting they exist within God's mind.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=plato+forms+mind+of+god -

The Forms

Plato sometimes referred to his Ideal realm as "more real" than material reality. His cave & shadow metaphor illustrated that concept. But I interpret his "eternal realities", not to mean more material & physical, but as more important for the theoretical purposes of philosophers.Your own response*1 to the OP erroneously implies that Plato was talking about Ideal Forms as-if they were real physical objects*2. I never interpreted his theory that way*3. — Gnomon

The excerpt below may seem off-topic to some, but I interpret A.N. Whitehead's Process Philosophy to be an update of Plato, in view of 25 centuries of philosophical haggling. But even that update is now out of date, since it predated the Big Bang theory and Quantum Physics. So, Process Philosophy may not be the last & final word on the Matter v Mind relation between Things & Essences, Objects & Processes, Realities & Idealities.

Still, the time-tested notion of Ideal Forms may be useful for understanding the distinction between unchanging eternal Potential and evolving temporal Actuality. Evolution can be imagined (philosophically) as the gradual actualization of unformed possibilities (Ideal Forms). Ontological BEING in the process of Becoming. :smile:

Whitehead's Forms :

Alfred North Whitehead's philosophy, process philosophy, uses the concept of "eternal objects" as a parallel to Plato's Forms, but with a significant inversion. While Plato viewed the Forms as ultimate, eternal realities, Whitehead sees them as dependent on actual occasions of experience for their actuality. Eternal objects are patterns and qualities, like "squareness" or "blueness," that are potential and become actual within specific events.

Here's a more detailed breakdown:

Plato's Forms:

Plato believed that the physical world is a mere copy or shadow of a realm of perfect, eternal Forms.

These Forms, like Beauty or Justice, are the true, unchanging reality, while individual objects in the physical world are imperfect reflections of them.

Whitehead's Eternal Objects:

Whitehead's eternal objects are similar to Plato's Forms in that they are abstract, unchanging qualities or patterns.

However, Whitehead argues that eternal objects don't have their own independent existence, but rather depend on "actual occasions" for their actuality.

An actual occasion is a moment of experience, a specific event in the process of becoming.

Eternal objects become actual when they are "selected" or "realized" by an actual occasion.

Actuality:

For Whitehead, the world is not a copy of a higher realm, but a dynamic process where actuality arises from the interaction of eternal objects and actual occasions.

Hierarchy:

Plato's theory is hierarchical, with the Forms at the top of the reality scale. Whitehead's system is more egalitarian, with both eternal objects and actual occasions playing crucial roles.

In essence, Whitehead inverts Plato's hierarchy, arguing that the process of becoming is more fundamental than the eternal objects themselves.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=whitehead+platonic+forms -

The Forms

Yes. For the same reason I ignore 99.99 percent of all technical philosophical papers.↪Wayfarer , ↪Gnomon

Ok, so you both will ignore the limits of Aristotelian modal logic becasue understanding the wider formal modal logic would require some effort. — Banno

However, if I thought it might shed some light on the OP question --- "what are The Forms?" --- I might expend the effort necessary to dissect abstract Logic and ideal Forms as-if they were physical objects. Your own response*1 to the OP erroneously implies that Plato was talking about Ideal Forms as-if they were real physical objects*2. I never interpreted his theory that way*3.

Instead, he was using as-if philosophical Metaphors*4 to create conventionalized images (names ; labels) of abstractions that non-experts can understand. There is no Ideal realm that we could get to in a space ship. Instead, it's a hypothetical construct that exists only in rational minds as an abstraction from places & domains in sensory reality.