Comments

-

The Case for Metaphysical RealismYes, the question "Why is there something instead of nothing" is an often-asked question.

Michael Faraday answered that question in 1844. I couldn't find details of what he said, but what I found agrees with the metaphysics that I've been proposing. — Michael Ossipoff

As I've argued, I don't find the idea of an answer in general plausible. If there is something because of X, then X itself is either the brute fact or itself unexplained.

Anyway, the metaphysics that I've been proposing answers that question, in terms of systems of inter-referring inevitable abstract facts. — Michael Ossipoff

But (I must ask again) are the people you love inevitable abstract facts? Is that how you experience them? For me relationships are among the highest things. Other people as people. Not just the idea of a person (which, like all ideas, has a certain shallowness) but the living presence of others. That my be my fundamental complaint about abstract theologies. They betray or ignore our direct experience of being with others, of sharing a practical world with others. This criticism doesn't apply to your sense of a sort of benevolent God, because that's a general sense that life and the world are good.

Kenneth Patchen wrote, "In general, why is everything so specific?"

As we were discussing, the particular way that this world is, is one of infinitely-many ways that the infinitely-many worlds are. There are infinitely-many of them, and ours is one of them. — Michael Ossipoff

I can't accept automatically that there are infinitely many worlds. On the other hand, the billions of lives I have nothing to do with are plurality enough. But your attempt to answer the why with what I'd call theology doesn't do it for me. I like that you can relate to wonder, but you're sending me mixed messages on this issue. That's fine. Just sayin'

All that's logically-necessary for our universe is a system of inter-referring abstract facts. Because those facts are inevitable, there's no brute-ness — Michael Ossipoff

I can't agree. The question would be 'why are they inevitable?' I guess we could call the bruteness subjective. I don't believe that so-called fundamental explanations can get the job done --on principle, according to how I understand explanation. The totality is untouchable in this sense.

So time isn't the only state of affairs. In fact, timeless sleep predominates, although of course sure, we aren't there yet, and won't be for a while. ...either at the end of this life, or (more likely) after a sequence of lives. — Michael Ossipoff

But it only predominates abstractly and quantitatively. We don't experience this sleep. As mortals we can contemplate (or try to) the world before and the world after our passing. But we're always here when we do that.

The world that you were born in likely had something to do with the person that you were. — Michael Ossipoff

I'd call that an understatement. Yeah, we're thrown into a particular body. We're given particular parents, a face we did not choose, and so on. Then it's even 'little' things like the books we happened to bump into as teenager's for instance. Or the things we were praised or blame for in our formative years.

Good conversation, btw. -

Unstructured Conversation about HegelHegel has a reputation of being unreadable, but he could give quite a speech.

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/1818/inaugural.htm...

We must regard it as commendable that our generation has lived, acted, and worked in this feeling, a feeling in which all that is rightful, moral, and religious was concentrated. – In such profound and all-embracing activity, the spirit rises within itself to its [proper] dignity; the banality of life and the vacuity of its interests are confounded, and the superficiality of its attitudes and opinions is unmasked and dispelled. Now this deeper seriousness which has pervaded the soul [Gemüt] in general is also the true ground of philosophy. What is opposed to philosophy is, on the one hand, the spirit’s immersion in the interest of necessity [Not] and of everyday life, but on the other, the vanity of opinions; if the soul [Gemüt] is filled with the latter, it has no room left for reason – which does not, as such, pursue its own [interest]. This vanity must evaporate in its own nullity once it has become a necessity for people to work for a substantial content, and once the stage has been reached when only a content of this kind can achieve recognition. But we have seen this age in [possession of] just such a substantial content, and we have seen that nucleus once more take shape with whose further development, in all its aspects (i.e. political, ethical, religious, and scientific), our age is entrusted.[9]

...

But even in Germany, the banality of that earlier time before the country’s rebirth had gone so far as to believe and assert that it had discovered and proved that there is no cognition of truth, and that God and the essential being of the world and the spirit are incomprehensible and unintelligible. Spirit [, it was alleged,] should stick to religion, and religion to faith, feeling, and intuition [Ahnen] without rational knowledge.[12] Cognition [, it was said,] has nothing to do with the nature of the absolute (i.e. of God, and what is true and absolute in nature and spirit), but only, on the one hand, with the negative [conclusion] that nothing true can be recognized, and that only the untrue, the temporal, and the transient enjoy the privilege, so to speak, of recognition – and on the other hand, with its proper object, the external (namely the historical, i.e. the contingent circumstances in which the alleged or supposed cognition made its appearance); and this same cognition should be taken as [merely] historical, and examined in those external aspects [referred to above] in a critical and learned manner, whereas its content cannot be taken seriously.[13] They [i.e. the philosophers in question] got no further than Pilate, the Roman proconsul; for when he heard Christ utter the world ‘truth,’ he replied with the question ‘what is truth?’ in the manner of one who had had enough of such words and knew that there is no cognition of truth. Thus, what has been considered since time immemorial as utterly contemptible and unworthy – i.e. to renounce the knowledge of truth – was glorified before[103] our time as the supreme triumph of the spirit. Before it reached this point, this despair in reason had still been accompanied by pain and melancholy; but religious and ethical frivolity, along with that dull and superficial view of knowledge which described itself as Enlightenment, soon confessed its impotence frankly and openly, and arrogantly set about forgetting higher interests completely; and finally, the so-called critical philosophy provided this ignorance of the eternal and divine with a good conscience, by declaring that it [i.e. the critical philosophy] had proved that nothing can be known of the eternal and the divine, or of truth. This supposes cognition has even usurped the name of philosophy, and nothing was more welcome to superficial knowledge and to [those of] superficial character, and nothing was so eagerly seized upon by them, than this doctrine, which described this very ignorance, this superficiality and vapidity, as excellent and as the goal and result of all intellectual endeavor. Ignorance of truth, and knowledge only of appearances, of temporality and contingency, of vanity alone – this vanity has enlarged its influence in philosophy, and it continues to do so and still holds the floor today.[14

... — Hegel

But how seriously can we take the social question? If our voice is more or less lost in the noise and the world rolls on without us, are we not largely just posing for ourselves and others? Aging and dying or just getting sick or poor rips us away from our righteous and/or utopian cultural criticism.

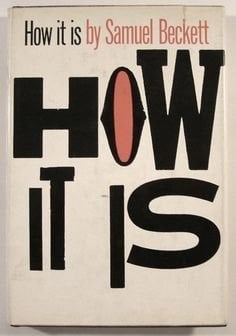

That's when the dark passages in the old King James or the wild prose works of Samuel Beckett speak the moment's truth. Or the poets and novelists --the true phenomenologists?

Hegel purveys the fantasy in its undiluted form of being the supreme know-it-all, God Himself incarnated not as a carpenter but as a dude that reads a lot. -

Unstructured Conversation about Hegel

Been awhile, but yeah. I liked some of it, but never real fell in love with guy. I have a vague sense that he was a bit righteous and effete for my tastes. -

Unstructured Conversation about HegelEven if Hegel exaggerated (or doesn't satisfy us today), his idea that the plurality of apparently opposed philosophies constituted one living, evolving, distributed philosopher leaping from dying individual to dying individual through the medium of language is seemingly worth being exposed to.

This work of the spirit to know itself, this activity to find itself, is the life of the spirit and the spirit itself. Its result is the Notion which it takes up of itself; the history of philosophy is a revelation of what has been the aim of spirit throughout its history; it is therefore the world's history in its innermost signification. This work of the human spirit in the recesses of thought is parallel with all the stages of reality; and therefore no philosophy oversteps its own time.

...

We must, therefore, in the first place not esteem lightly what spirit has won, namely its gains up to the present day. Ancient Philosophy is to be reverenced as necessary, and as a link in this sacred chain, but all the same nothing more than a link. The present is the highest stage reached. In the second place, all the various philosophies are no mere fashionable theories of the time, or anything of a similar nature; they are neither chance products nor the blaze of a fire of straw, nor casual eruptions here and there, but a spiritual, reasonable, forward advance; they are of necessity one Philosophy in its development, the revelation of God, as He knows Himself to be.

...

At this point I bring this history of Philosophy to a close. It has been my desire that you should learn from it that the history of Philosophy is not a blind collection of fanciful ideas, nor a fortuitous progression. I have rather sought to show the necessary development of the successive philosophies from one another, so that the one of necessity presupposes another preceding it. The general result of the history of Philosophy is this: in the first place, that throughout all time there has been only one Philosophy, the contemporary differences of which constitute the necessary aspects of the one principle; in the second place, that the succession of philosophic systems is not due to chance, but represents the necessary succession of stages in the development of this science; in the third place, that the final philosophy of a period is the result of this development, and is truth in the highest form which the self-consciousness of spirit affords of itself. The latest philosophy contains therefore those which went before; it embraces in itself all the different stages thereof; it is the product and result of those that preceded it. We can now, for example, be Platonists no longer. Moreover we must raise ourselves once for all above the pettinesses of individual opinions, thoughts, objections, and difficulties; and also above our own vanity, as if our individual thoughts were of any particular value. For to apprehend the inward substantial spirit is the standpoint of the individual; as parts of the whole, individuals are like blind men, who are driven forward by the indwelling spirit of the whole. Our standpoint now is accordingly the knowledge of this Idea as spirit, as absolute Spirit, which in this way opposes to itself another spirit, the finite, the principle of which is to know absolute spirit, in order that absolute spirit may become existent for it. I have tried to develop and bring before your thoughts this series of successive spiritual forms pertaining to Philosophy in its progress, and to indicate the connection between them. This series is the true kingdom of spirits, the only kingdom of spirits that there is - it is a series which is not a multiplicity, nor does it even remain a series, if we understand thereby that one of its members merely follows on another; but in the very process of coming to the knowledge of itself it is transformed into the moments of the one Spirit, or the one self-present Spirit. This long procession of spirits is formed by the individual pulses which beat in its life; they are the organism of our substance, an absolutely necessary progression, which expresses nothing less than the nature of spirit itself, and which lives in us all. — Hegel

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/hp/hpfinal.htm

Metaphors like the Holy Spirit come to mind. Language is deeply and utterly social. We are great as individuals, one might say, to the degree that we can enter deeply into this social language and make our thinking relevant to what is highest in all us. To the degree that we think deeply or truly, it might be said that God is continuing his journey of self-knowledge in and through us. But maybe it's better to speak of God's self-invention through human history as well as through human concept. Desire drives the process. Work changes the world that changes us. Even or especially war plays a role here, as forms that oppose God's expansion and/or enrichment of Himself are violently destroyed.

Yet all this 'God' talk is arguably a mask for an unbounded humanism. The human thinker is the self-knowing essence of reality. Time works towards the god-man's complete self-consciousness, which is also the end of history.

Ideology, right? Yeah. But good stuff, even if only to taste and to spit out. The general shape of it applies IMV to the journey of individual self-consciousness. We work through various stages of understanding the world and our place in it. Do we ever really drop anything? Or do we add another layer? Recontextualize the past without forgetting it? We contain neutralized past selves with our present selves. I think of Shakespeare. He was and was not Hamlet and Falstaff. They lived in the theatre of his mind. Unseduced, he could nevertheless play with hundreds of perspectives --fundamentally a worldly man, no stranger to the usual lust and ambition, no saint --though he understood saints, I'd guess, without having to be one. -

What does it mean to say that something is physical or not?That's the ground of being you're talking about,i presume, our situatedness or thrownness. And the most rigorous form of awareness for Heidegger, what he calls authenticity, is a not being caught up in the particulars of what comes into our horizon of concern, the this and the that of experience, but rather experiencing as a whole in its always being oriented ahead of itself.I suppose this could be understood as a getting behind the past. — Joshs

Right. I more or less read the authentic mode as the phenomenological mode. It's one of the slippier themes in Heidegger (to me), but he does speak in The Concept of TIme of authentic Dasein attaining clarity about its temporal being. I suppose one can bear the angst of abnormal discourse without thematizing it, however. But I doubt anyone could thematize it without experiencing it.

But I really don't like the word Dasein anymore. It sticks in my throat. It becomes theological in its association with a famous brand name. 'Idle talk' can itself become part of idle talk, for instance. This is not at all directed at you. I've just read lots of Heidegger criticism, lately (and the man himself). It's fascinating how any particular approach to describing factic life can 'harden' into a crust that blocks the phenomenon. The words become academic and lose their force. Everything tends to become clever and precious as it succeeds. I feel the need to keep reaching for new words. I think slang evolves for the same reason. -

What does it mean to say that something is physical or not?I don't agree, though, that we live wholly in language if that is just taken to mean verbal or written speech. We live in languages. We live in visual language, musical language, mathematical language, and of course body language, as well as 'linguistic' language. — Janus

Right. Life is bigger than language. It's even bigger than all of those languages you mention. The way the body moves through the world comes to mind. The way we claim stairs, step into the bathtub, embrace those we love, chew out food, etc. I was just focusing on the blind know-how of speaking/writing at that particular moment. It's a fairly new theme/realization for me. It's so easy and traditional to snap into a certain artificial mode when doing philosophy. -

Physical vs. Non-physicalI will counter, "See, the logico-mathematical formulations of physics represent a conceptual language so generic as to mask the different ways in which the physicists in that room are understanding the meaning of the supposedly universal concepts of their science ". — Joshs

Beautiful. Exactly. Pure math is also a good example. No one has to know what is being talked about --not as long as the standards of what constitutes productivity are fixed. Normal discourses are cozy. There's the 'guilt' or 'risk' of personality in abnormal discourse. It's uncanny. Someone might actually believe you and act on that belief. It's safer inside the lab coat, being lived by the one.

From this I form the heretical conclusion that such philosophical conceptualizations are in fact more precise than logic-mathematical empirical ones. — Joshs

Interesting perspective. I agree, where 'precision' is understood in an eccentric but important sense. After all, philosophy 'places' the quantitative precision. It lands it in the total context. -

Unstructured Conversation about HegelIt's still arrogant and lacking in skepticism. — charleton

To me he's just a vivid personality. At his best, he's great (for my purposes). At his worst, I can't say. Because I stop reading when I'm bored. We can debate whether he's over-rated, but who cares, really? The whole game of famous names no longer appeals to me much. There's a tendency to make implicit arguments from authority. There's a tendency to let it be known that one has read this or that 'officially great' philosopher. Then one can praise or blame them, implying that one is brilliant enough to understand them or, even better, brilliant enough to understand them and see how they went wrong.

Either praising or blaming seems to depend on a sort of fame worship. No one plays this game much with the unknowns.

That's why I like the idea of just focusing on ideas, independent of their source. Sure, indicate your influences if you must, so it doesn't feel like plagiarism. But I'd at least personally like to get beyond the itch to project my having-read-a-real-lot. As I see it, I don't possess what I can't express in my own English. Once I do possess it, it's independent of the source. -

What is Scepticism?I don't understand what you mean when you say that the whole thing is 'artificial'. All of us have a clear idea of what it is for something to exist, since, as Descartes pointed out, one has a first hand awareness of one's own existence. — PossibleAaran

I find the critics of the Cartesian approach pretty convincing. I'd like to know what you'd make of Heidegger's The Concept of Time. It's a short, early draft of his most famous work. It's about 80 pages of philosophical revolution.

You say that this whole language of 'existence' and 'perception' is artificial, but I don't think it is at all. I'm immediately aware both of my existence and my perceiving, so in what sense is it artificial? Without an answer to that, I can't see what you mean in saying that you desire theory closer to 'non-philosophical life', since it seems to me that the concepts 'existence' and 'perception' can be understood merely by reflection on your own mental life and so they are, as it were, as close to your life as could be! — PossibleAaran

We operate, though, with a lot of inherited metaphysical baggage. It's so familiar that we take it for granted. For instance, are we thinking substances? Do objects in the word exist in physics time, physics space? Or is there a different kind of existential time and existential spatiality that we cover up with what 'should' be there, with what has become an educated common sense that no longer checks itself against the flow of experience. For the most part we 'comport' ourselves nontheoretically in the world. We don't even have a language for this as a general rule, because it's so automatic as to be almost invisible to the theoretical mind.

The theoretical mind just stares at objects. They become concept-organized sensations, perhaps. But the non-theoretical mind uses objects as tools. Or has pillow talk with the wife. The theoretical epistemology-obsessed approach has nothing to do with this kind of living.

Being-in-the-world and being-with-others is something like a pre-theoretical 'sense' or phenomenon that operates as an in-explicit foundation for our theorizing. We 'know' that we are in a shared situation or world in a pre-rational way. I can't prove this. I can only point to the phenomenon. In the same way, I can only define words in terms of other words. We just do grasp language as a whole, as a sort of mysterious condition for the possibility of theoretical talk. The artificiality comes in when this vast background goes unnoticed and we play with a few concepts on the foreground. We don't see that we play on the mere surface of an ocean of dark knowhow. -

What does it mean to say that something is physical or not?Can you explain what you mean by "get behind the past"? Do you simply mean to think about or understand it or are you referring to something else? — Janus

Sure. It's my favorite theme lately. Given your post above, none of this will probably sound new to you. I'm largely inspired by Heidegger, though I like the idea of making it my own --emphasizing the ideas I like and finding new metaphors, etc.

The 'living' or 'primordial' past is the 'how' of the present. This 'how' is the method we take for granted, the pre-grasp or invisible background. The form of life. It hides in its familiarity. It's our manner of questioning that goes unquestioned as we question the 'what' of our focus.

To get behind the (living) past is to see 'around' all the crust of yesterday's living choices that we've inherited as blind necessities. The apparently necessary (the blindly inherited paradigm) becomes optional once we strip away its familiarity. The 'living' past is the water that the fish doesn't see. It is the medium that quietly controls what can and cannot appear as the message.

Normal discourse is 'message' focused. It uses the medium in an unconscious manner. Abnormal discourse 'attacks' or destroys this past. Just making it conscious is sufficient. A homier example:the living past is the glasses we don't realize we are wearing. But to get completely behind the past would be to pluck out our eyes, since we live in language and language is historical. -

Unstructured Conversation about HegelThis is all very well and nice, but practicing what you preach is my minimum standard. If he wants to take the skeptical stance, he can't remain a Theist.

And if he thinks he has transcended the problems he lays out then he is deeply arrogant and wrong headed.

What use is Hegel when you have Hume whose skepticism he had till the end? — charleton

Perhaps you'll agree that his theism (or my rough portrait of an interpretation of it) is far from non-theoretical theism. For many, he might as well be an atheist. Calling self-knowing reality God and insisting that the cruelty in history is necessary for God to become God is far from ordinary theism. Theists tend to want an afterlife and a fixed truth and a fixed moral law. They want the Eternal. Hegel sacrifices all of that. God himself is not outside of time. He needs time. He is born through time. He grows like a tree or a human infant.

It's even 'Satanic,' one might say. Since what we really have here is a ferocious humanism that wears the cloak of tradition. Hegel himself was (roughly, in his own mind) the most updated version of God. Reality knows itself 'rationally' or 'essentially' in human language. The philosopher is reality's self-knowing eye. It's goal is to know itself as freedom, as God. What it overcomes is the traditional theism that projects God outward as a sort of hidden or distant object.

The Trumpet of the Last Judgment by Bruno Bauer is an ironic investigation of the Satanic/humanist core of Hegel's philosophy. It's a great, largely forgotten text. -

The Case for Metaphysical RealismAnd just because there’s a metaphysical explanation for why and how it happened doesn’t make it any less amazing. — Michael Ossipoff

This is a good issue. For the most part we are immersed in life. We don't have time for wonder. We desire or fear certain situations and work to attain or dodge them. We grind away in the familiar. I remember a few incidents when I was younger when I was suddenly shocked that there was anything at all. I was also shocked by the specificity of what was. 'It is exactly this way and no other. There are three weeds at this Northeast leg of the park bench. That particular plane with its particular passengers flies overhead.' These days I have a better argument for brute facticity, and yet it's rare to feel wonder as I did once.

I'm biased towards brute facticity because it makes the world new. But I also think it's logically necessary, since nature is a system of necessity, as I see it, and the whole of nature (all that is insofar as we can explain things) can be put in relation to nothing. To put it in relation would only to be expand it, to include yet another entity in the nexus of necessary relationships.

I know what you mean, but in a way it is the only state of affairs. Against the background of physics time it is indeed a blip. But it's all we know. Time-for-us is being late for an appointment and hating every red light. Or dreading what morning brings. Or opportunity fading away. It is death quietly and steadily approaching us, maybe tomorrow or maybe twenty years from now. It is an uncertain resource and/or the possibility of suffering.Time is short. It isn’t the usual state of affairs. — Michael Ossipoff

Sure, but the larger metaphysical basis, substrate, environment of a person’s life is of interest in that life. The overall nature and character of what metaphysically is, has a lot to do with how we interpret and feel about this life. As I mention below, what is there when we look up from our day-to-day business? — Michael Ossipoff

I very much agree. Really I'm doing my own kind of metaphysics. I enact a notion of the noble. I too am a sort of scientist, albeit one who theorizes about the limits of theory and theory's tendency to flee from the ambiguity and complexity of experience. The 'total vision' of what life is and means is indeed quite important.

But maybe we don’t suffer as much, or more than necessary, depending on our perspective on what there is, and what’s going on. — Michael Ossipoff

I agree here, too. And metaphysics or basic world views are poetic acts, too. We enjoy finding the words. -

Physical vs. Non-physical

Can we make the way a word functions in the world totally explicit? I don't think so. At best you can sharpen the meaning as much as possible for a particular purpose within a local conversation, it seems to me.

In general, knowing what 'physical' means is (IMV) a dimly understood knowing-how to get along with others in the world. Perhaps every use of 'physical' is unique, albeit with a family resemblance. Just because we have this fixed sequence of letters from a fixed alphabet P H Y S I C A L doesn't, in my view, indicate that the 'meaning' has the same kind of quasi-mathematical static, definite presence as the mark. The foundation of our making sense of things seems to lie mostly in darkness. -

Unstructured Conversation about HegelHere's Hegel being something of a concept-monger. He sure doesn't like his Divinity vague and indeterminate.

The man who only seeks edification, who wants to envelop in mist the manifold diversity of his earthly existence and thought, and craves after the vague enjoyment of this vague and indeterminate Divinity – he may look where he likes to find this: he will easily find for himself the means to procure something he can rave over and puff himself up withal. But philosophy must beware of wishing to be edifying.

Still less must this kind of contentment, which holds science in contempt, take upon itself to claim that raving obscurantism of this sort is something higher than science. These apocalyptic utterances pretend to occupy the very centre and the deepest depths; they look askance at all definiteness and preciseness of meaning; and they deliberately hold back from conceptual thinking and the constraining necessities of thought, as being the sort of reflection which, they say, can only feel at home in the sphere of finitude.

— Hegel

Sorry, Hegel. That's all you. -

Unstructured Conversation about HegelHe's talking about shit you absorb, mostly uncritically, the points of reference we take for granted, and that this could be problematic "deceptive". — charleton

But that's more or less what I meant. The 'how' or the method or the approach is what we take for granted. As I read him, Hegel is criticizing a certain understanding of philosophy that is taken for granted. Within this taken-for-granted paradigm, the 'bad' philosophers do indeed ask questions and doubt things. But what they didn't think to question has them trapped. They questioned the 'what,' the focus of their attention. They argue passionately about God and truth. They do word math with the subject and the object and the who-knows-what. But they assume that these words have fixed, clear meanings. They want to do a kind of theological math, after all, and that's what they'll need language to be like.

They also assume that God or Truth is a frozen already-finished entity. All they have to do is snap the right word-numbers together. But for Hegel the meanings of the words evolve as we do philosophy. Even more radical, we create God (or self-conscious Reality) as we do philosophy. Or God creates himself through us as we try to figure out the truth about God/Reality. God has to misunderstand himself as a fixed object. God has to misunderstand language as a sort of math. Such creative errors are the stairway to reality becoming fully conscious of itself.

It's pretty wild stuff. It's not software for everyday life, but it is 'speculatively' plausible --or just a fascinating dynamic auto-theology.

What is “familiarly known” is not properly known, just for the reason that it is “familiar”. — Hegel

We take the medium (our own manner of taking) for granted. It's a smell that we've become used to. Yet the medium controls what messages are possible. The quote above points backs to our otherwise untested pre-grasp of the situation, which is the foundation of our conscious grasp. I think this squares with what you wrote, though I've thrown in some different metaphors. -

What is the point of philosophy?Scientific theories require no justification nor foundation, as if any such thing were possible. They are the last idea standing after they have withstood all the criticism we are capable of subjecting them to. — tom

What I have in mind as an unacknowledged-by-some foundation is the know-how of everyday life. We understand an ordinary language (a meta-language for science). We know how to exist socially, to form relationships. We don't doubt our senses. We know how read the instruments. We have a basic understanding of the counting numbers, which can lead us to the rational numbers, etc. We don't question and test everything. We don't doubt that others are really there, even if we can't experience their emotion-sensation-consciousness in the same way they do. We don't bite our tongue when we chew our food. We stand a certain distance in conversations so as not to freak people out. And so on.

In short, there is a dim foundation of shared, trusted half- or non-conscious assumptions that set the stage for science. The base of the pyramid is sunk in the sand. So scientific theories have been left standing after all the criticism that seemed relevant in terms of human purposes. Even that is perhaps an approximation. Among other things, it assumes that the institutions of science function perfectly --that valid criticisms weren't repressed or ignored. That individual scientists in power aren't emotionally attached to this or that experiment.

To be clear, I like science. But I find the tendency to think of science as a replacement for philosophy more or less absurd.

Not sure what that means, but I have a vague inkling that no one really does that. — tom

It happens all the time, though maybe I'm exaggerating for rhetorical effect. Look around. The sceintific vision of objective reality is taken wholesale out of its context as a disavowed (unquestioned) metaphysics. Space is the space of physics. Time is the time of physics. Humans are the animals of biology. If none of this is objectionable to you, then you may be missing out on some good philosophy.

I can't speak for you. But I think of science largely as a tool. It gives us comfort and free time to do things that are better or higher than science. For some (and even for me when it comes to particular slivers of science), research itself is one of the deepest pleasures. I get that. But humans (and philosophy) have more things to do than (only) obsess over epistemology and sing the glory of science.

The 'problem' is a focus on the public and objective that leaves our personal, mortal situation more or less unthought. Human time is finite. The future and the past mingle in some non-mathematical present. The now isn't a real number. It's a non-repeatable moment and a baby-step toward the grave. Space is the space of a two-footed body and of human eyesight, of obstacles and the object to be reached. Then of course there's the fact of being a distinct person --exactly the distinct person obliterated in the abstract interchangeable observer of science. This forum is a zoo of distinct and stubborn personalities. Where are all the unbiased people hiding? It's a role we play in a lab coat, which is not to say that no one plays it well. The point is that science is a particular ideal, a purification in one direction of this mess we're in. -

What is the point of philosophy?I agree. Getting old, it is decrepitude and its many indignities that are the live issue. Death becomes a solution more than a threat. — apokrisis

Right. I think that's where certain authors are right about 'existential' time. It is directed and finite. Gold won't buy it back. And even the usual lifespan is not guaranteed.

The biological perspective is my thing. So I really like the idea that life is like riding a bicycle, or the tilt of the sprinter.

We hang together on the edge of falling apart by flinging ourselves constantly forward. The beauty of living lies in this constant mastery over a sustaining instability. We stay in motion to keep upright. Then eventually we slow and it all falls apart.

So there is a self-making pattern. Individuals come and go, but the pattern always renews. And it is the possibility of the material instability that is the basis for the possibility of the formal control. Life is falling apart given a sustaining direction for a while. — apokrisis

Very well put. -

What is Scepticism?If the lives of the Idealist and the Realist are identical in behaviour then they are not functionally different and the distinction is pointless — Inter Alia

Yeah. I think OLP and pragmatism exploded the 'ism' approach to philosophy for me. I see that there's an -ism on the end of pragma- there, but I read it as a sort of anti-ism or trans-ism that tries to get behind merely verbal disputes.

Maybe you've already looked into him, but I think William James is great. Here's a few quotes:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5116/5116-h/5116-h.htmFor the philosophy which is so important in each of us is not a technical matter; it is our more or less dumb sense of what life honestly and deeply means.

...

The pragmatic method is primarily a method of settling metaphysical disputes that otherwise might be interminable. Is the world one or many?—fated or free?—material or spiritual?—here are notions either of which may or may not hold good of the world; and disputes over such notions are unending. The pragmatic method in such cases is to try to interpret each notion by tracing its respective practical consequences. What difference would it practically make to anyone if this notion rather than that notion were true? If no practical difference whatever can be traced, then the alternatives mean practically the same thing, and all dispute is idle.

...

Pragmatism represents a perfectly familiar attitude in philosophy, the empiricist attitude, but it represents it, as it seems to me, both in a more radical and in a less objectionable form than it has ever yet assumed. A pragmatist turns his back resolutely and once for all upon a lot of inveterate habits dear to professional philosophers. He turns away from abstraction and insufficiency, from verbal solutions, from bad a priori reasons, from fixed principles, closed systems, and pretended absolutes and origins. He turns towards concreteness and adequacy, towards facts, towards action, and towards power. That means the empiricist temper regnant, and the rationalist temper sincerely given up. It means the open air and possibilities of nature, as against dogma, artificiality and the pretence of finality in truth.

— James -

Physical vs. Non-physical

Great sketch. All those thinkers are great, and those are strong paraphrases. You left off Heidegger, I note.

For me the 'first wrong move' is 'wrong' with respect to a particular and ultimately personal purpose. I want to 'speak the truth' about life, be a poet who gets it righter if not right. But it's also a matter of style, of being more wakefully present in the non-theoretical aspects of life. The alternative is to force the mess of experience into nice little word machines, constraining the experience anxiously. So the 'first wrong move' is assuming a bookish theoretical approach toward existence, one might say. Or picking up the 'how' of research unquestioned. But lots of this is already in the thinkers you mentioned, and I don't claim to be telling you something you don't know in this post.

But on the boxes: We see various boxes from the outside. To recognize the box as box is to transcend it, to subject the box (category) to a new freedom. What we took for object turns out to be the malleable projection of a subject. In retrospect, we see that we were locked in a certain perspective. We interpreted (we realize) our tunnel vision mistakenly-in-retrospect as a tunnel. (We can ignore the limits of subject-object talk for the moment. We have to pick up this imperfect junk to say anything.)

At some point, we recognize this structure of perspective-transcending as such. We can even think of philosophy as the art of seeing the box and thereby making it optional. We might even call this process 'freedom,' since the apparently necessary is transformed into the merely optional. Then philosophy becomes a kind of acid that eats away not simply at fixed ideas but at otherwise fixed paradigms. But why should we do this? To some degree, I think there is just a raw pleasure in transgression and exploration. But it also allows for a wealth of perspectives we can use and also put down when not appropriate. If an individual can bear the dissonance, then he or she becomes a richer, more flexible personality. (I'm less interested in social questions. Life is short.) -

What is Scepticism?Simple, such a belief has been entirely harmless for the (more than I'd care to mention) years of my life so far. Can anyone say the same of Idealism? — Inter Alia

Fallibilism?

You're touching on a great issue here. Probably some could say the same of idealism. But if the realist and idealist live the same kind of sane life in terms of action (avoiding crimes, maintaining relationships), what then is the weight of such positions? In theory, they are big deal. Everything is real or ideal, etc. But in practice it looks like slapping this or that name on the shame shared reality.

Political isms probably get more attention precisely because they are better indicators of behavior. We care more about how others treat us than we do about the names they slap on the familiar world we share. -

Unstructured Conversation about HegelIn philosophy as such, in the present, most recent philosophy, is contained all that the work of millennia has produced; it is the result of all that has preceded it. And the same development of Spirit, looked at historically, is the history of philosophy. It is the history of all the developments which Spirit has undergone, a presentation of its moments or stages as they follow one another in time. Philosophy presents the development of thought as it is in and for itself, without addition; the history of philosophy is this development in time. Consequently the history of philosophy is identical with the system of philosophy. — Hegel

As far as I know, no one hammered this idea home like Hegel. I'd be glad to be corrected. The path to truth is the truth itself. But the path (thinker on the path) only recognizes this having gone down the path. He is (potentially) the thing he seeks. His seeking of what hides from him within himself is the unfolding of that same truth. God 'builds' God as God seeks God. And God exists only within finite individuals, as their shared higher thinking and feeling. But individuals and societies are intertwined. So philosophy, distributed throughout these individual minds, grows alongside and dialectically with social practice. The story goes, I think, that a more or less perfect, non-alienating society ofsaintscitizens arrives.

It's a beautiful idea. I don't really expect the end of history. But what a vision! -

Unstructured Conversation about Hegel

Oh yes. I've read his bio. Even in my first philosophy book (Durant's Story) I think this was mentioned. I find it hard to choose. They both pay attention where the other one does not. -

What is the point of philosophy?

I know. It was a rhetorical question. The point is that scientism (as distinct from science) ignores all of this. It's all 'really' quarks, etc. This 'really' is metaphysical for scientism in a way that it doesn't admit. They can have a ball with that. But I can have a ball picking my own horse and arguing with you about it. (This is my idea of fun.)

Another example: Neil deGrasse Tyson. He's a pretty lovable guy. But even a brilliant man like that doesn't get 'why is there something rather than nothing?' I sort of get it. Lots of religious types themselves think that this is quasi-scientific question, for which they have a quasi-scientific answer --God as hidden object. Both sides are obsessed with 'junk' they can be correct and certain about. -

Unstructured Conversation about Hegel

That was an ugly, seemingly covetous moment for Schopenhauer. If memory serves, Schopenhauer more or less ignored the historical. From his 'mystic'-biological perspective, the same thing happened again and again. There was nothing new under the sun. Man didn't change. He had the same illness subject to the same cure generation after generation.

Hegel, on the other hand, understood that he himself was only possible as Hegel because of so much that had come before. Man did change. God himself evolved. The truth evolved. The truth or cure was something like a final stage of the lie, of the illness. Error itself became truth in its tendency to eat itself. If the fool persists in his folly, he shall become wise. If the understanding persists in its ripping-out of partial truths, it will end up with the whole truth. As those partial truths fail, they patch themselves up in a way that accumulates. But this happens in a social context. So truth cannot arrive until different kinds of societies come and go, until the right conceptual language is painstakingly created by a kind of universal mind that only exists in particular philosophers who pass on their work (the current state of Mind) through the 'machine' of language. (Or that's what I got, roughly.) -

How 'big' is our present time?I agree with you that the mathematical continuum is not an accurate model of the nature of the real world. What's interesting is that physicists are trained to think of an instant of time as a real number t. What's the acceleration at time t, what's the temperature?

The math helps them to craft interesting theories. But the world is definitely not the same as the mathematical real line. The world is not a set of dimensionless points of space and instants of time. — fishfry

Right. The theoretical picture of nature reminds me of a grid that's loosely projected on an everyday experience of just being in the world with furniture and other people. I agree that this grid is not the thing itself. I'd also stress that even the objectively real is something that has to be filtered out of tangled personal experience. We basically scrub everything personal away. In fact we have mortal being with particular faces and sense organs and histories, etc., experiencing things. But (for good reason) blend and filter such experience into an image of the object, the public. This kind of thing probably goes even deeper, to the use of words like 'experience' and language in general. We pretend/assume that 'experience' has a fixed, universal meaning, etc. As others have said, we project being on becoming. But that's no final statement either. 'Fail again. Fail better....Till nohow on.' -

The Case for Metaphysical RealismOf course, I agree with all of that. The Atheist philosopher’s attribute-less god doesn’t make sense to me either.

.

Let me just clarify about my Theism:

.

It seems to me that metaphysics leads to the conclusion that what there metaphysically (describably, discussably) is, is insubstantial and ethereal. …implying an openness, looseness and lightness, …and something really good about what is, in a way that’s difficult to describe, explain or specify.

.

…a feeling or impression that there’s good intention behind what is.

.

That’s it. That’s my Theism. It’s an impression and a feeling. I don’t ordinarily call it Theism, because, as you suggested, “-ism”s are more for arguing…compartmentalizing and dividing people. — Michael Ossipoff

For what it's worth, I like this theism. I find it honest to speak of impressions and feelings. I also like the humility about the difficulty of expressing the higher things. If the higher things were neat little systems, they would almost have to be mechanical trivialities.But, it seems to me that what I’m talking about is something also evidently felt by many Theists, including those who believe in Literalist allegories. …but more significant than the Literalist allegories. So even though I don’t share all the beliefs of the Biblical Literalists and the more progressive selective Literalists, many of them are still onto something, …what they likely emotionally mean when they speak of God. Of course some Theists, maybe usually the more progressive ones, are more consciously aware of that than others.

.

As I said, it’s an impression or feeling. It isn’t something to assert, and can’t be proven to someone else, but I don’t doubt it either. Sureness without proof isn’t scientific? Fine. As I said, proof and assertion are only for logic, mathematics, physics and (to some extent) metaphysics. It would be meaningless to speak of proof, or need for doubt without proof, for a meta-metaphysical impression. As I said, it would be like speaking of electroplating an adverb. — Michael Ossipoff

Well said. I agree. The word 'God' and other spiritual words can play all kinds of roles. Those who can only think in terms of proving mechanical certainties often project this purpose on others. So they think religion is stupid only because they are trapped in a scientistic conception of it --and (to be fair) because many religious people themselves are trapped in such a conception.

I like 'electroplating an adverb.' That's good.

But I only apply that “how” where it’s called-for and appropriate. I don’t mean it or offer it outside its range of applicability. I often criticize Scientificists for wanting to apply science outside it legitimate range of applicability. You’re, quite rightly, saying that too, about the “how” of metaphysics, logic, and mathematics. Yes, I’m always criticizing that over-application of science’s approach. And yes, of course that goes for metaphysics too, which has a similar approach.

. — Michael Ossipoff

I'm seeing that we probably have more in common than otherwise. Would you agree that metaphysics is something like a 'logical' world-revealing or existence-revealing poetry? We want it to cohere, to be plausible. We don't want fiction. It functions as the higher truth. But since it establishes the criteria by which all statements are judged, it's also not objective.

But I only talk that way in metaphysics and when I talk about logic, mathematics or science. I agree that the language of metaphysics isn’t for everyday life, and is only verbal argument. And, in fact of course, verbal description or explanation doesn’t, at all, ever even come close to experience or Reality. …and of course I realize that the metaphysics that I talk is entirely verbal and conceptual. …and couldn’t describe or substitute for experience, or describe or explain Reality.

.

I often use the analogy that the difference between metaphysics and Reality, experience, is a bit like the difference between a book all about how a car-engine works, vs actually going for a ride in the countryside. — Michael Ossipoff

Since we both seem to see things this way, I guess it's just a matter of taste or current interests that has me harping on the gap and you doing metaphysics with an awareness of its limitations. On the other hand, my thinking on the 'how' and the 'what' (inherited from influences) is a kind of metaphysics.

But you aren’t saying, are you, that the matter of what metaphysically is, doesn’t meaningfully and relevantly relate to our larger lives? — Michael Ossipoff

I do find it relevant, just as I find diet and exercise relevant, or style relevant. We humans (especially thinkers) love our words. So for me it's largely a matter of self-creation or self-editing in terms of the words we use for what is highest and truest. As a matter of taste, I like the idea of being a thinker of the storm and the blood --more of a poet than a theologian. But I used to be more of a theologian, so this is something like changing the way one dresses or deciding that X is cooler than Y. I put that in blunt terms (terms that might embarrass not you but more rigidly solemn thinkers) strategically. Slang is sometimes closer (in my view) to the way we really think and feel. A stiffer more respectable language is perhaps a mask we wear not only for others but for the mirror.

But let’s not imply that the study of metaphysics (or physics, mathematics or logic) prevents someone from being immersed in life. — Michael Ossipoff

I agree. I don't want to imply that. But I can imagine someone being word-drunk and thereby being a bad friend or lover. I'm sure I've been guilty of that. It's the love and respect I have for certain less theoretical people that wakes me up from this. Sure, I could point them to some fascinating thinkers. But are they lacking something essential? I don't think so, even if that would suit my vanity.

As for the relation between Theism and love and relationships: Well, I spoke of the good intent behind what is. Gratitude for that is a reason to try to embody it, repay/share some of it, at least within our limited human ability, in our own lives, actions and relations. As Theists often say it (and as you suggested), God is Love. — Michael Ossipoff

Well said. I like 'God is love.' I find other interesting uses for 'God' too --the idea that God is a personification of reality, or that God is the obscure object of spiritual desire. In my view, humans naturally seek virtue, but our conception of virtue is malleable. This allows for terrible cruelty sometimes. In King Lear, Edmund decides that Nature is his Goddess. He practices his religion by throwing those who trust him most under the bus to be a king. I suggest that this often vague concept of what is noble, good, virtuous, etc., is or tends to be the hub of a worldview. -

A question on the meaning of existenceEach of those abstract facts is valid with or without minds, or any larger context or medium. — Michael Ossipoff

This doesn't make sense to me, or not if facts are made of language.

A proposition can;t be true and false, and so we don't live in a willy-nilly-self-inconsistent impossibility-world. That's why I say that logic has authority over experience, — Michael Ossipoff

God is love. Is that a proposition? Is a metaphor a proposition? How is such a statement intended? What does 'God' mean? What is love? Is 'God is love' meaningless just because it doesn't fit some attraction 'fantasy' of meaning that makes the metaphysician's job easier?

So your vocabulary of objective rationality dependent on evidence from a physical world, implying metaphysical assumptions which underle the various theologies I mentioned, becomes challenged when the subject-object, mind-world, consciusness-material dualisms are dissolved. — Joshs

Exactly. The taken-for-granted method is the blindspot. -

The Brothers Karamazov DiscussionYou guys make me want to reread Brothers. I have a better memory of The Possessed and Crime and Punishment. Suffice it to say that Dostoevsky is a master. His characters are vivid and haunting. In extreme moments, this or that character will come to mind. Forgive me for not adding much. I did want to cheer generally this discussion of Dostoevsky. It's great to see things like this here.

-

What is the point of philosophy?I suspect that The Truth, or the ordinary secular truths we can actually grasp, are the consequence of our relationships with one another, and science, in that order. — Bitter Crank

Yes, in that order. If I give scientism hell, it's only because I think people in fact experience one another in a non-theoretical sense that transcends not only the lingo of science but also of metaphysics and theology. To me it is somewhat 'obvious' that we don't have a verbal handle on the fullness of what it is to be human. I assume that the lives of others are roughly like mine. This gut-level half-conceptual assumption is the kind of thing I'm talking about, though. Preconceptual or half-conceptual know-how.

For whom is their lover atoms and voids or a system of facts or a ghost in the machine? All these cute little concepts are pasted over something that's far harder to describe. I'm not anti-science, etc. There's just a tendency to pretend that life is reducible to physical or biological science that amuses and dismays me. Have such people ever been in love or buried someone? You know what I mean? Or heard great music? Or been moved by a novel? Life is big. -

What is the point of philosophy?Is mortality more something you worry about when you are old or when you are young? — apokrisis

In my experience, the young are more terrified of death. As we age, we start to understand its attractions. We go from terror to mixed feelings.

I didn't stress it, but I include the failure of the body in the problem of death. We don't usually just drop dead. Things fall apart first. The vitality we took for granted seeps away. For context, I'm between youth and old age. My remaining vitality beings to appear in its true finitude. This first-person switch from the future stretching endlessly to a certain number of Christmases and Thanksgivings is food for thought. Life takes on a new vividness. It's a loud dream. To some degree we choose to continue dreaming it.

On their deathbed, most people regret not spending more quality time with family, friends and passions. A life devoted to striving and achievement seems unbalanced in retrospect. The cultivation of the individuated self - the idea of making one big difference to society rather than a lot of small differences for those closest at hand - seems overblown at the far end of life. For quite natural reasons. Just as it seems the most important thing of all back at the start of adult life. — apokrisis

Yes. This sounds right to me. Youthful ambition is world-historical. Youth refuses to believe that the world will likely no more notice its departure than it did its arrival. I think seeing the 'hugeness' of the world and life is a sort of 'philosophical' realization. My voice is one among many. Those who locally love me give a damn, and that's usually it. Even intellectual fame would involve (I presume) something like a caricature or alienation. It has no obvious 'deep' meaning.

I've got to agree as I've felt it too. And I think finding it "fascinating" speaks to a suitably balanced assessment. — apokrisis

Thanks. I'm definitely looking for the right tone. Some of life's beauty lies in the death of all things. All things are temporary and elusive. We like to chase things. The receding seduces. The ungraspable beckons. What is more sickly sweet than an unplucked opportunity as it dies? Neither victory nor disaster endures. Neither the heroic deed nor the most terrible crime. It comes and goes like music.

Life is both futile and worthwhile, both absurd and meaningful. And this isn't paradoxical, just an expression of the range of possible philosophical reactions we have learnt to manifest. We feel the full space of the possible - in a way that a lack of philosophy would render inarticulate.

And that in itself is both fascinating and unsettling — apokrisis

We are 100% on the same page here.

The full space of the possible.

So the only problem with philosophy is that once you have habituated its dialectical tendencies, they infect everything you could think about. Once you create range, you always then have the dilemma of locating yourself at some definite point on the spectrum you've just made.

The alternative to that is to float above your own spectrum of possibilities in some detached and free-floating manner. Which is where "you" start becoming a highly abstract kind of creature even to "yourself".

Do I care? Do I not care? At every moment I could just as easily make a different choice on that.

Thank goodness life provides its social scripts that "one" can always grab hold of, so as to decide the matter for the passing moment, eh? Ah, the existentialism of being an existentialist — apokrisis

Good points. Sometimes hand-wringing theory-mongering is absurd and inappropriate. -

What is the point of philosophy?Husserl (and Merleau-Ponty and Heidegger also) was doing something I interpret as quite different and radical than simply talking about what is conventionally termed 1st person perspective. — Joshs

I agree. My understanding of it includes getting behind all of this encrusted theoretical language. To the things (factic life, existence, being there) itself. But this is a goal. On the way to that goal we have to cut through the pre-interpretations. We have go back behind the first wrong move as much as possible. Fail again. Fail better. Become a little more wakeful. -

The Case for Metaphysical RealismWait a minute. Isn’t there anything that isn’t anthropomorphic? Surely that’s over-broad. — Michael Ossipoff

When it comes to what we care about, no. In my opinion. It may be an exaggeration to get the point across. Accusations of anthropomorphism don't ring true for me. What's the 'sin' here? I think the sin is supposed to be that we are less accurate about reality because of a bias toward human-likeness. Sure. QM violates ordinary experience. But it works. So we endure it. On the other hand, it makes no sense to worship or revere anything unrelated to the human. Not to me. 'God' or X has to be 'good' in some way, good-for-humans, good-for-me.

.

Though metaphysics isn’t the same as science, it’s like science in some ways. Definitions should be explicit and consistently-used. Statements should be supported. Metaphysics, like physics, doesn’t describe all of Reality, but definite uncontroversial things can still be said about both. — Michael Ossipoff

Perhaps. But this is your assumption. This is the loaded 'how' that you bring to the situation. But my 'how' is the tendency to think this 'how' and get behind this 'how,' to open up the situation.

What if language isn't what you need it to be here? What if strict definitions force you to abandon the fluidity of language in ordinary life? Your system seems well thought out, better than average. But from my point of view it's still a kind of theoretical construction that a philosopher comes up with at his desk, alone in his study. Then he goes outside and immerses himself in the usual inexplicit knowhow of moving among objects and interacting with other human beings. His conceptual art falls away. It doesn't describe the way he actually lives. It's a sort of model airplane building, fun for a certain kind of conversation. I'm not saying there's anything wrong with that. I'm just pursuing my own notion of 'objectivity' that does justice to non-theoretical life. I want to open the window of the study and let the storm of life in. We are mortal, loving, fearing, lusting, etc., human beings first and system-builders second. In my view, the system builders (cosy in their study) forget the storm. So they bring their systems to those immersed in life and meet with bewilderment.

I suppose for 'spiritual' or 'esthetic' reasons I want my words to have a kind of legitimacy or weight-- or awareness of the passing storm of life. I make my living at a technical job. All hail science. But I don't live for it. It's a small piece of life. Or maybe even a medium sized piece. But what of love and relationships? And how do these fit in to our theologies? -

What is the point of philosophy?

I like Feyerabend. It's been awhile, but his Conquest of Abundance is pretty great. I hope I remember the title correctly. But I could also drag in Whitman here. Or lots of other poets. They are phenomenologists, one might say. They try to speak the truth about experience, to let the fish see the water. The science-religion debate is (at worst) like an argument between those who lost their left eye and those who lost their right eye. For 'spiritual' or 'aesthetic' reasons some of us strive for a kind of wholeness and richness of experience. An opposite drive exists toward some citadel of invulnerable correctness. 'Here, finally, is the systematic truth, the one true method, the machine-like set of words that puts to death the hassle of inquiry forever.' I can't curse that urge. It too seems deeply human. -

Unstructured Conversation about HegelI'm not sure I'd characterise this as phenomenology, but standard metaphysics, this is not about experiencing life but conceptualising it. — charleton

Consider the title of the book. No doubt Heidegger was more radically phenomenological. And lots of Hegel is still too metaphysical for my taste. But I think the quoted passage is pretty damned phenomenological. The 'familiar' is the 'how' of our grasping that we take for granted. We tend to focus on the 'what,' the message as opposed to the medium. But here Hegel is pointing at the medium. The water is usually invisible to the fish. He's pointing at the water. -

What is the point of philosophy?Of course. And the general goal of philosophy or critical thinking would be something along the lines of "arriving at the truth of reality". But even that could be disputed by those who claim it to be akin to an exercise in poetry or whatever. — apokrisis

That's a pretty good description. But we might also speak of attaining a kind of emotional equilibrium, of making peace with death or 'evil,' etc. Of living and dying well. The phrase 'adaptive doing' comes to mind, where doing includes thinking. As far as poetry goes, I think it's fair to include the pleasure we take getting some truth down. It's not just the ring of truth but the quality of that ring. The King James translation is great English, for instance. The same ideas in a lamer English don't ring the same way. As I see it, we are more Kirk than Spock.

I generally agree with the rest of your post. But perhaps you neglect the position of the mortal individual with a particular history. You mention the individual pole in passing, but don't have much to say about it, which is fine. But what of the individual who comes to term with his smallness on the world stage? With the impotence of his notion of the way the world ought to be? Born into a kind of chaos, he will die in it. Also it seems fair to expect the species itself to go extinct.

In short, we operate within a sort of finitude and absurdity, granting these assumptions. We are future-oriented beings with long-term projects and social hopes. Yet projecting far enough ahead reveals a kind of futility. Of course we can 'forget' or 'justify' our deaths in terms of social hopes, artistic accomplishments, offspring, religion. But we reason about these things. We wrestle within ourselves. I'd include this kind of talk within 'philosophy.' -

Unstructured Conversation about Hegel

As I read it, he's talking about a certain kind of philosopher taking classic metaphysical terms for granted --as if they had fixed meanings that were ready to be put in play. Instead, as I understand him, the meanings of all these terms are dynamically and systematically related. So these points aren't really secure at all. Thinking evolves dialectically as a system, as a whole. To me this is good phenomenology. It digs beneath the crust of convention. It goes back before the first wrong move.

IMV, there are not too many words there. But of course you are welcome to your dislike. -

What is the point of philosophy?A discipline doesn't have to be self-aware to be useful, but that doesn't mean that there is no more to an understanding of what a science does that what is provided in their language of description. — Joshs

Good point. It may be that a certain discourse functions well because it ignores its own foundations. What we might call scientism is something like a vague distrust of any kind of thorough conceptualization or investigation of these foundations. On philosophy forums, there's usually a fear of religion at play. Any lack of reverence for science 'must' lead to some kind of religious position --because surely there's no 'rational' or intellectual reason to place science in the total context of life. For scientism, something like a scientist as priest metaphor seems to function in the background. -

Unstructured Conversation about Hegel

To be fair, some of Hegel's prose annoys the crap out of me. But he was sometimes quite clear and even eloquent, at least in translation. I find it hard to take you at your word that you have read much Hegel. Maybe you have. I don't know. But I've railed against thinkers before myself --and then come to love them.

Does the quote below really sound like gibberish to you? It sounds to me like a potent critique of a certain kind of philosophy.

What is “familiarly known” is not properly known, just for the reason that it is “familiar”. When engaged in the process of knowing, it is the commonest form of self-deception, and a deception of other people as well, to assume something to be familiar, and give assent to it on that very account. Knowledge of that sort, with all its talk, never gets from the spot, but has no idea that this is the case. Subject and object, and so on, God, nature, understanding, sensibility, etc., are uncritically presupposed as familiar and something valid, and become fixed points from which to start and to which to return. The process of knowing flits between these secure points, and in consequence goes on merely along the surface. Apprehending and proving consist similarly in seeing whether every one finds what is said corresponding to his idea too, whether it is familiar and seems to him so and so or not. — Hegel -

Unstructured Conversation about Hegel

Ah yes, and others. I like the idea of actually 'looking' at this flow every once in awhile to see if I'm not floating away on a pile of seductive abstractions. I've been manically-ecstatically inspired by certain thinkers in a way that closed me off to other people. My words were the words. In retrospect, they always appeared like oversimplifications. Maybe that's what we always work with, oversimplifications. -

Unstructured Conversation about HegelHegel= obscurantist, mystic. Russell did not understand him and it is my view that Hegel did not understand himself most of the time. — charleton

That's pretty silly. Hegel is often as clear as Russell. And Russell could be a real dufus at times. Repeating negative gossip is lazy, man. Not that I really give a damn if you or anyone else respects Hegel. By all means, enjoy your prejudice. I decided not to like David Bowie for awhile once. It was fun.

ff0

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum