-

Leontiskos

5.6kCircles are straight lines. Squares are circles. Logic is just the manipulation of symbols. And there are no laws of logic. Really a brilliant thread, all around. Everyone here deserves a pat on the back. :wink:

Leontiskos

5.6kCircles are straight lines. Squares are circles. Logic is just the manipulation of symbols. And there are no laws of logic. Really a brilliant thread, all around. Everyone here deserves a pat on the back. :wink:

I can't wait until tomorrow, when we show that 2+2=5.

It would appear obtuse to the layman, and maybe it just is. — Leontiskos -

schopenhauer1

11klaws of logic — Leontiskos

schopenhauer1

11klaws of logic — Leontiskos

I thought we agreed, formal logic is conventionalized ways of thinking :p. It can only be an approximation of our thinking, but not our thinking itself. -

Leontiskos

5.6k- The closer you get to the foundation, the surer it becomes. For example, modus ponens is arguably the most basic inference or law of propositional logic, and I don't see that it fails.

Leontiskos

5.6k- The closer you get to the foundation, the surer it becomes. For example, modus ponens is arguably the most basic inference or law of propositional logic, and I don't see that it fails. -

schopenhauer1

11kThe closer you get to the foundation, the surer it becomes. For example, modus ponens is arguably the most basic inference or law of propositional logic, and I don't see that it fails. — Leontiskos

schopenhauer1

11kThe closer you get to the foundation, the surer it becomes. For example, modus ponens is arguably the most basic inference or law of propositional logic, and I don't see that it fails. — Leontiskos

What's the "foundation" mean here?

Presumably, natural human reasoning, something akin to inferencing, let's say, is of an imprecise nature. It just needed to be "good enough". However, the kind of reasoning we developed- generally intertwined with linguistic capacity, and certain kinds of episodic memory, can get formalized culturally into more precise logical thinking. This is especially helped by the ability to write out the symbols.

From here, these more precise "crisp" arguments, might be said to have a foundation, perhaps Platonically (pace Frege and Plato). And thus, you might mean some kind of transcendental foundation (Platonic). Or, perhaps, like Kant, you think that it is internally a priori, and simply part of the human cognitive faculties. I challenge this, as evolutionary vagueness seems to be at play. Math is contingent on cultural preciseness, not internal preciseness. However, even math's preciseness and internal logic in its own system, doesn't necessarily have a foundation outside itself. Newton's Calculus system is not as accurate as Riemann's system, for example. And thus "foundation" can thus mean:

1) Human cognition- I challenge this usually works in vague approximations, not crisp exactitude.

2) Platonic transcendentalism- I am not sure what this would mean other than logical truths are somehow existent in some real way.

3) Naturally occurring patterns- this might be physical laws, for example. But this isn't really the logic itself. Logical systems, like mathematics, are applied to observable phenomenon, and "cashes out" in experiments and technological use. -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

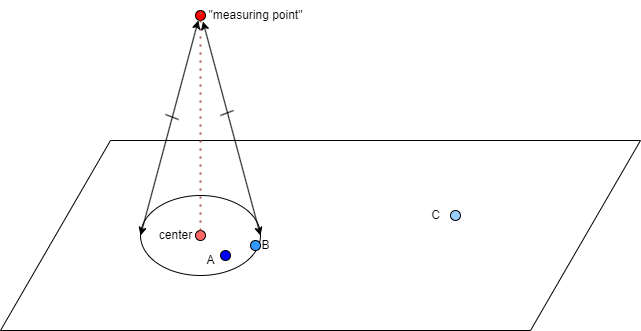

There's nothing much to the geometry, but here's a picture to start with.

(There's other ways to look at this. You could of course go ahead and treat the "determining point" as a center and make a circle on a plane right there, then project that circle onto a parallel plane. Blah blah blah.)

Having separated the point that determines the circle from the center of the circle, it just occurred to me that you could treat it separately, do a lot of stuff with it. To start with, you don't have to project to the center of the circle in the plane, you don't have to use that orthogonal projection, but could send it (translate it) to any point A, B, or C, anywhere in the plane.

Then I thought there might be something interesting if you grouped these projections into buckets, those that send it into the circle, those that send it far away, and so on. And I thought there might be some interesting stuff there ― maybe allowing the axis to wobble a little, and see how stable your buckets were, and lots of other stuff.

But then it occurred to me what probably caught my eye about this.

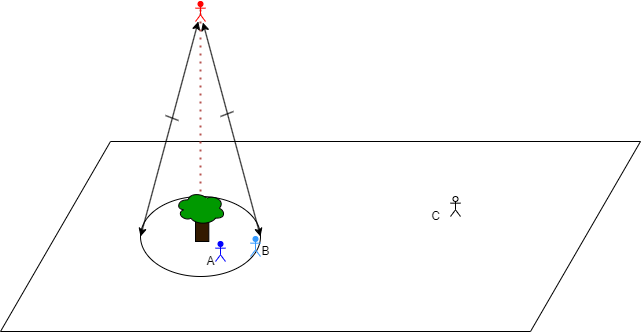

If instead of thinking of the points A, B, and C as being projections of the "determining point", what if you went the other way, and thought of any point in the plane translating to the point off the plane that determines this circle.

Suddenly that cone looks like a field of vision, and the other points are other actors who are triangulating their view of ― in this case ― a tree (or whatever) with the red guy at the "determining point". (We'd probably want to move the red guy onto the plane with the A, B, and C, and create a new notional plane orthogonal to this one to represent Red's f.o.v., but whatever. At this point the whole setup is merely suggestive.)

And then it should be obvious there is a meaningful difference between being in the circle and outside it, because that determines whether you are also in Red's cone of vision.

It happens I've been reading about triangulation and joint and shared intentionality in apes and humans (Michael Tomasello), so it was probably on my mind, and that's why the whole arrangement, splitting one point into two (center/determiner), then splitting that second point into two as well (determiner/projected) ― it all suggested something to me, and this was probably it.

I wonder if there is something else interesting just to the geometry, but that's no doubt above my paygrade. -

Banno

30.6kJust the shortest path between two points. So pick two points on a sphere, draw the shortest line, then extend that. The result is a great circle. The maths can be done intrinsically, without reference to some coordinate system in which the sphere sits.

Banno

30.6kJust the shortest path between two points. So pick two points on a sphere, draw the shortest line, then extend that. The result is a great circle. The maths can be done intrinsically, without reference to some coordinate system in which the sphere sits. -

Leontiskos

5.6k- I only meant the foundation of the logical system. Frege's foundation is explicitly modus ponens, and many propositional systems similarly ground themselves in modus ponens. In fact we can think of modus ponens as the basis for the material conditional in propositional logic, where the modus ponens inference is more intentionally foundational to the system than the idiosyncratic behavior of the material conditional (which we are considering elsewhere). I tried to speak a bit to the odd foundationalness of modus ponens <here>.

Leontiskos

5.6k- I only meant the foundation of the logical system. Frege's foundation is explicitly modus ponens, and many propositional systems similarly ground themselves in modus ponens. In fact we can think of modus ponens as the basis for the material conditional in propositional logic, where the modus ponens inference is more intentionally foundational to the system than the idiosyncratic behavior of the material conditional (which we are considering elsewhere). I tried to speak a bit to the odd foundationalness of modus ponens <here>.

If you want something more universally foundational, I would point to the principle of non-contradiction, and ultimately its unique character of being simultaneously subjective and objective, which Kimhi alludes to. A lot of the silliness in this thread is either a direct or indirect attack on the PNC. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Those supposed foundations are addressed in the Russell article.What's the "foundation" mean here? — schopenhauer1

Few implementations of propositional logic start with modus ponens. It's most often just a theorem. -

Leontiskos

5.6k

Leontiskos

5.6k

Earlier logicians had drawn up a number of rules of inference, rules for passing from one proposition to another. One of the best known was called modus ponens: ‘From ‘‘p’’ and ‘‘If p then q’’ infer ‘‘q’’ ’. In his system Frege claims to prove all the laws of logic using this as a single rule of inference. The other rules are either axioms of his system or theorems proved from them. — A New History of Western Philosophy, by Anthony Kenney, 155

Contemporary logicians like Enderton and Gensler begin the exact same way. Other starting points are possible, but they are not all on a par if one wants to do actual logic. Of course for metamathematics the starting point is arbitrary. Banno, under the spell of metamathematics, will be at a complete loss before your question about how true reasoning and logic interrelate. As Apokrisis has pointed out numerous times, Banno begins and ends with nothing more than a bit of posturing. -

fdrake

7.2k

fdrake

7.2k

This was cool. I would need to sit down with some algebra to understand it properly though. Regarding the projection - there will be a lot of degrees of freedom if you get to choose an arbitrary projection onto the plane, so I suppose picking a specific projection to the centre point in the plane and looking at its preimage under that projection is the idea you had in mind? -

fdrake

7.2kStraight lines on spheres? That's interesting too. — creativesoul

fdrake

7.2kStraight lines on spheres? That's interesting too. — creativesoul

Yep! It turned out a property that uniquely characterised straight lines in our normal kind of space also applied to spheres, and it makes great circles. It's the taxicab circle thing again. Straight lines are only the things we expect in Euclidean ("flat") space. But that's an artificial restriction.

Edit: even flatness. The volume in the room you're in is flat. -

Moliere

6.5kI am not sure if you can have an "epistemic endeavour," that is unrelated to being though. What is our knowledge of in this case? Non-being? — Count Timothy von Icarus

Moliere

6.5kI am not sure if you can have an "epistemic endeavour," that is unrelated to being though. What is our knowledge of in this case? Non-being? — Count Timothy von Icarus

I'll quote Gillian Russell here from the opening of her One True Logic?:

Logic is the study of validity and validity is a property of arguments. For

my purposes here it will be sufficient to think of arguments as pairs of sets and

conclusions: the first members of the pair is the set of the argument’s premises

and the second member is its conclusion. An argument is valid just in case

it is truth-preserving, that is, if and only if, whenever all the members of the

premise-set are true, so the conclusion is true as well.

The domain of logic, then, might be thought of as a great collection of

arguments, divided into two exclusive and exhaustive subcollections, the valid

and the invalid, the good and the bad, and the task of the logician as that of

dividing one from t’other. — Gillian Russell

Suppose we had a formal system that answered all our questions about physics, or maybe some area of it like fluid dynamics. How could it have "no relation" to being? At the very least, it would have a relation to our experiences, which are surely part of being. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Humean skepticism comes to mind -- it could be that our logical discourse is constrained by our mental habits rather than by being. So it goes with causation: We cannot help but to draw causal inferences by our habits of thought, but the inference we draw is unjustified (insofar that we accept Hume's notion of causation, at least - but here I'm trying to point out how an anti-realism is possible, so that's enough).

I'm more tempted to say that if we have no more questions about physics this says more about our lack of curiosity than it does about our knowledge of being.

I want to do leap year physics. You get a nice three year break. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Here's the bit where reality kicks in: You can do leap year physics. But you won't be paid for it.

What you'll be paid for is tracking patterns which people like to track, which usually involves manipulating the world in some way which we perceive as regular. It's this social bit that stops the infinite possibilities, though that's not exactly a pure rational reason or a philosophical gatekeeper. -

Moliere

6.5kThey are supposed to be objections to Aristotle, so yes, of course they do. You might as well have objected to Mr. Rogers by telling us that you prefer people who put on shoes. Mr. Rogers puts on shoes in every episode. — Leontiskos

Moliere

6.5kThey are supposed to be objections to Aristotle, so yes, of course they do. You might as well have objected to Mr. Rogers by telling us that you prefer people who put on shoes. Mr. Rogers puts on shoes in every episode. — Leontiskos

I don't exactly object to classical logic, though -- I'm saying it has limitations, not that it's wrong in every case.

To clarify -- the wiki on syllogism has a clear rendering of what I mean by classical logic:

There are infinitely many possible syllogisms, but only 256 logically distinct types and only 24 valid types (enumerated below). A syllogism takes the form (note: M – Middle, S – subject, P – predicate.):

Major premise: All M are P.

Minor premise: All S are M.

Conclusion/Consequent: All S are P.

The premises and conclusion of a syllogism can be any of four types, which are labeled by letters[14] as follows. ... — wikipedia

etc. etc.

Notice how these can be rendered in predicate logic in that article. These things aren't at odds, exactly. It's only that they are different.

And so it goes with non-classical logics. These aren't opposed, per se -- they rely upon a different set of assumptions and look for the patterns of validity after that.

Now in a given philosophy we'll want a particular logic, or particular logics for particular ends, but the logician need not adhere to one philosophy. Why would they? What would the point be, given that here the logicians are doing their thing without Aristotle's assumptions?

As has been pointed out numerous times, this is just gibberish. What do you mean by (1)? — Leontiskos

It's the name for a sentence.

A name denotes an individual.

The individual is an English sentence.

The sentence is "This sentence is false"

(1) is a shorthand to make it clear what "This sentence" denotes.

In a logical sense there's no reason to exclude this individual if we want our theories of logic to be entirely general -- to apply to all individuals. Denoting a sentence is surely not violating logical possibility -- it's the nefarious choice of self-reference with the "... is false" predicate which breaks the logical ambition and creates a paradox that calls for an answer.

One answer, which you've provided, is that the sentence means nothing.

It's not the only one though. -

frank

19kI don't exactly object to classical logic, though -- I'm saying it has limitations, not that it's wrong in every case. — Moliere

frank

19kI don't exactly object to classical logic, though -- I'm saying it has limitations, not that it's wrong in every case. — Moliere

Right. Logical pluralism is saying that there is no one logic that applies to all cases. A logical pluralist would agree that the LONC is useful... where it's useful. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

I don't exactly object to classical logic, though -- I'm saying it has limitations, not that it's wrong in every case.

Just a helpful point of clarification, "classical logic," is confusingly the logic developed by Frege and co. relatively recently. There is no good catch-all term for logic before the late 19th century. People call it "Aristotlean," but then this tends to miss everything between Aristotle and 1850 or so.

There was a Stoic logic distinct from Aristotle's, but it disappeared. The big difference I recall is that Artistotle primarily saw logic as an instrument of science/philosophy whereas the Stoics thought it was a proper field of study. The dominant modern view seems to blend these two. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

What you'll be paid for is tracking patterns which people like to track, which usually involves manipulating the world in some way which we perceive as regular.

And why do we perceive it as regular? That's the key problem I see here. If the answer is "for no reason at all," that's a problem. If "it just is," is acceptable some places, it seems acceptable any place. Yet people almost always give up on "it just is," when they feel they have a good explanation for something, making it simply a catch-all to fill gaps and end discussions.

I'm also not sure what "being" is supposed to be if it isn't what is given to thought.

As for the quote, the same problem seems to remain. It defines logic in terms of truth, "truth-preserving," etc. I don't think these are terms are unproblematic or explainable solely in terms of formalism. And it certainly seems that logic cannot be the study of non-being either. -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kI would need to sit down with some algebra to understand it properly though. — fdrake

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kI would need to sit down with some algebra to understand it properly though. — fdrake

If I'm doing something dumb, it's okay to just say that.

Regarding the projection - there will be a lot of degrees of freedom if you get to choose an arbitrary projection onto the plane — fdrake

Yes exactly.

Here again is how I got here.

In school, we learn to think of circles this way:

1. You've got a plane.

2. Pick a point in the plane.

3. Find all the points in the plane equidistant from that point.

4. That set of points is your circle.

5. The point you picked in (2) is the center of your circle.

But it needn't be that way.

Your great circle example, or the conic sections we learn in Algebra II, are different.

1'. Pick a point in 3-space.

2'. Find all the points equidistant from that point.

3'. That set is a sphere, or a 2-sphere.

4'. Any coplanar subset of the points in (2') is a circle, or a 1-sphere.

If you now look at the plane of the the circle in (4'), there is a subtle difference from the plane in (4): the center is not marked. No point in the plane was used to generate the circle ― although, of course, the circle has a center you can find. But in the schoolboy's circle, you never have to go find the center ― you pick that point to start with.

(There's a direction-of-fit thing here: in one case, the center determines the circle; in the other, the circle determines the center.)

When you find the center, you might ask, is it related in any special way to the point in 3-space we picked (1')? And of course it is. There is exactly one line orthogonal to the plane that passes through that original generating point, and it passes through the plane at the center of the circle as well.

And you might then think of the center of the circle as a projection of the center of the sphere. And it is, but it's entirely optional. That projection comes after we already have the circle. It's the canonical projection alright, but you could also project that point to any point on the plane, because this projection is just a thing you're doing ― the circle doesn't need it, isn't waiting for this projection, you see? -

Moliere

6.5kJust a helpful point of clarification, "classical logic," is confusingly the logic developed by Frege and co. relatively recently. There is no good catch-all term for logic before the late 19th century. People call it "Aristotlean," but then this tends to miss everything between Aristotle and 1850 or so. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Moliere

6.5kJust a helpful point of clarification, "classical logic," is confusingly the logic developed by Frege and co. relatively recently. There is no good catch-all term for logic before the late 19th century. People call it "Aristotlean," but then this tends to miss everything between Aristotle and 1850 or so. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Cool.

I mean logic prior to Frege. The square isn't found in Prior Analytics, but I would consider the likes of Frege, Peirce, and Cantor as part of the new logic which encompasses Aristotle's studies on validity, if not his entire project.

And why do we perceive it as regular? — Count Timothy von Icarus

I think that's a question for metaphysics rather than logic -- and which explanation one chooses will complement this or that metaphysic. These are different questions because we can reconcile various kinds of anti/realism with various kinds of monism/pluralism/nihilism in logic. This isn't to take a side on realism or anti-realism, but to demonstrate that the question of realism isn't the same as the question between logical monism, pluralism, or nihilism.

The nihilist account seems to get along with anti-realism, but it's possible to reconcile a realist metaphysic with a nihilist logic, and an anti-realist metaphysic with a monist logic. If that's the case I conclude that they are different questions and logicians need not answer the metaphysical question in exploring monism, pluralism, and nihilism.

Even on a realist account, though, I'd say we frequently find patterns that are not real -- we find regularities because we like them so much that we find one's that are false as well as true. This is what we mean by delusions and hallucinations and such.

Which is really just to convert the question of ontology -- what is it that we know about? -- to epistemology -- how do you know the true from the false?

I'm also not sure what "being" is supposed to be if it isn't what is given to thought. — Count Timothy von Icarus

It's a concept in metaphysics whose meaning cannot be articulated, but only approached. If I take a page from Sartre Being is transphenomenal. If I take a page from Heidegger, then the question of the meaning of being is itself an unarticulated assumption of all philosophy prior which relies upon the notion of presence.

Is non-being somehow not-known? If I am looking for someone in a bar because we said we'd meet and I do not see them then isn't this an account of absence-in-presence?

Either way I'd say that the question of being is not a question of validity -- another demonstration from logic.

If the moon is made of green cheese then Alfred is the president

The moon is made of green cheese

Therefore Alfred is the president

The actual truth-value of these sentences isn't in question when talking about logic. It's the form between the sentences under the assumption that if the premises are true that the conclusion follows. But since the moon is not made of green cheese the question of being -- what is -- differs from the question of validity, and logic is this study of validity. -

Leontiskos

5.6k(There's a direction-of-fit thing here: in one case, the center determines the circle; in the other, the circle determines the center.) — Srap Tasmaner

Leontiskos

5.6k(There's a direction-of-fit thing here: in one case, the center determines the circle; in the other, the circle determines the center.) — Srap Tasmaner

There are different ways to rationally conceive or define (and draw) a circle. Equidistance from a point is one. Aristotle prefers another, "The locus of points formed by taking lines in a given ratio (not 1 : 1) from two given points (KM1 : GM1 = KM2 : GM2 = ...) constitute a circle":

But what a circle is and how a circle is drawn are two different things. Similarly, two different ways of conceiving a circle are immaterial to the question at hand when they are formally equivalent, as is the case here. When I gave some arguments against square circles, I suggested that one could quibble with the arguments, but not oppose them in any way that goes beyond a quibble. I think that has turned out to be right. Aristotle's circle and Euclid's circle are formally equivalent. The definition of a circle is not specifying the manner in which a circle is created; it is specifying what a circle is. -

schopenhauer1

11k

schopenhauer1

11k

So my problem again here is the use of "foundational". This is a slippery word. The way you are all using it is basically "axiomatic". I take "axiomatic" to mean "don't ask me anything further, this is as far as I'm going", or simply "duh!". It really doesn't mean much except that we need to start "somewhere" and "this seems like a good place to start". Without getting into the obvious rejoinder of the problem of circularity or "brute fact", I see the problem as more complicated.

Axioms themselves are grounded in something. One might call them "intuitions". One might call them "Platonic truths" living in some divine realm (above the divided line!). Either way, it is that I believe to be foundational. Axioms then become a digital/crisper version of the intuition/natural reasoning. From THERE, you can then work out a whole bunch of complicated formal language rules. But only after the initial FOUNDATIONAL translation from NATURAL reasoning to the "crisp" axiomatic ones of formal logic. -

Leontiskos

5.6kThe way you are all using it is basically "axiomatic". I take "axiomatic" to mean "don't ask me anything further, this is as far as I'm going", or simply "duh!". It really doesn't mean much except that we need to start "somewhere" and "this seems like a good place to start". — schopenhauer1

Leontiskos

5.6kThe way you are all using it is basically "axiomatic". I take "axiomatic" to mean "don't ask me anything further, this is as far as I'm going", or simply "duh!". It really doesn't mean much except that we need to start "somewhere" and "this seems like a good place to start". — schopenhauer1

Eh. If you take it to mean axiomatic, then it has nothing to do with a good place to start. If you take it to mean a good place to start, then it is not axiomatic. Axioms are not good places to start except in a purely formal or economical sense. This chimera is understandable, given that my use of "foundational" was nothing like "axiomatic." Quite the opposite.

Again, the PNC is a more universal foundation or first principle than modus ponens. It is a foundation in the same sense that the first few feet of the trunk of a Redwood is a foundation. It is stable in a way that the upper branches are not, and folks never directly contravene the PNC. They only do so indirectly when they have climbed out onto limbs and lost track of where they are. -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kWhen I gave some arguments against square circles, I suggested that one could quibble with the arguments, but not oppose them in any way that goes beyond a quibble. I think that has turned out to be right. — Leontiskos

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kWhen I gave some arguments against square circles, I suggested that one could quibble with the arguments, but not oppose them in any way that goes beyond a quibble. I think that has turned out to be right. — Leontiskos

As you like.

It seems to me you think this is a question that can only ever be asked in one way and in one context, and therefore it only ever has one answer.

You can do that, and you can be right. Your response to a counterexample is "Well I didn't mean that, I meant this" and your honor is preserved. In the context you had in mind, you're still right. The counterexample isn't one.

Pick up a length of pipe. Look at it from the side and it's rectangular. Look at it straight on, it's circular. Done. "But I didn't mean that."

But you also seem to think the context you have in mind for any question that arises is the only context it can possibly arise in. I tend to have less confidence in my own omniscience, but you do you. -

Leontiskos

5.6kPick up a length of pipe. Look at it from the side and it's rectangular. Look at it straight on, it's circular. Done. "But I didn't mean that." — Srap Tasmaner

Leontiskos

5.6kPick up a length of pipe. Look at it from the side and it's rectangular. Look at it straight on, it's circular. Done. "But I didn't mean that." — Srap Tasmaner

A circle does not have a depth dimension. If we were talking about ropes we would have a different case.

I mean, if we define circles as squares, then sure, we can have square circles. But that's not what circles are. Redefining words in an attempt to achieve substantive conclusions does not strike me as good philosophy. We can talk about whether a material "instantiation" is ever a circle or circular, and I of course concede that in a strict sense there are no material instantiations of circles (and that if the great circle is conceived in this way then it is not a circle). But that is a far cry from the conclusion that there are square circles.

At the bottom of this whole thing are important questions about philosophical motivations. When I asked @fdrake about his motivations he said that, "shit-testing is standard mathematical practice." In other words, he has to adopt the persona of an extreme skeptic to see if his ideas hold up. This is a Cartesian mentality through and through, and I submit that it is a bad one. Granted, it is more applicable to mathematics than philosophy generally, but I tend to think it conflates science and mathematics in important ways. Beyond that, when I introduced the term "square circle" into the thread, it was as a metaphor for non-mathematical contexts. In such contexts "shit-testing" really is just Cartesian method, the age-old error of mistaking philosophy for mathematics or indubitable knowledge. -

schopenhauer1

11kEh. If you take it to mean axiomatic, then it has nothing to do with a good place to start. If you take it to mean a good place to start, then it is not axiomatic. Axioms are not good places to start except in a purely formal or economical sense. This chimera is understandable, given that my use of "foundational" was nothing like "axiomatic." Quite the opposite.

schopenhauer1

11kEh. If you take it to mean axiomatic, then it has nothing to do with a good place to start. If you take it to mean a good place to start, then it is not axiomatic. Axioms are not good places to start except in a purely formal or economical sense. This chimera is understandable, given that my use of "foundational" was nothing like "axiomatic." Quite the opposite.

Again, the PNC is a more universal foundation or first principle than modus ponens. It is a foundation in the same sense that the first few feet of the trunk of a Redwood is a foundation. It is stable in a way that the upper branches are not, and folks never directly contravene the PNC. They only do so indirectly when they have climbed out onto limbs and lost track of where they are. — Leontiskos

I get what you are saying, but I still think you are using foundation as "axiomatic", in the definitions I described- that is to say, "This seems like a good place to start". But really you must sus out the actual "foundation" from which this axiom derives. That takes a meta-theory beyond the axiom itself (of the PNC let's say). If we sus out what your particular theory is, it seems like something akin to either an evolutionary intuition or a Platonic necessity. Either way, the foundation is deeper than the principle itself.

Edit: Notice, I am not saying the axiomatic foundation is arbitrary. There is good reason it is selected. It seems to be the case everything revolves around it in logical workings, let's say. But I am saying what is this then grounded in? That is the foundation. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Pick up a length of pipe. Look at it from the side and it's rectangular. Look at it straight on, it's circular. Done.

This was Mandelbrot's key insight in coming up with fractional geometry. What is "smooth" at one scale is not at others, etc.

Likewise, a miter saw cutting wood is not generally considered a "chaotic" process. It's results are extremely regular on the scales we tend to care about for carpentry. Yet at a fine enough grain, it becomes extremely susceptible to strong variance due to minor changes in initial conditions.

Personally, I love C.S. Peirce on this issue. He's a big forerunner on these sorts of insights.

However, an I may have lost track of the point of the conversation, these do not seem like instances of contradictions to me, nor of particularly difficult cases for either logical realism or logical monism. TBH though, once they are properly caveated I find a lot of "logical monisms," and "logical pluralism" to be pretty much indistinguishable. If there is a material difference it goes over my head.

I guess a "strong" pluralism would declare that there are multiple equally valid/applicable logics but no morphisms between them? I just find it hard to imagine how this could be the case, since it seems that, by definition, they must have similarities in virtue of the fact that they are equally applicable to the same things.

And then a "strong monism," would presuppose a "one true formal system?" But that doesn't seem particularly plausible either. -

schopenhauer1

11kAnd then a "strong monism," would presuppose a "one true formal system?" But that doesn't seem particularly plausible either. — Count Timothy von Icarus

schopenhauer1

11kAnd then a "strong monism," would presuppose a "one true formal system?" But that doesn't seem particularly plausible either. — Count Timothy von Icarus

As I was saying to Leon, the "foundation" to logic would be a meta-logical theory, not the axioms/logical systems themselves. -

Leontiskos

5.6k- Good post. :up:

Leontiskos

5.6k- Good post. :up:

-

As I was saying to Leon, the "foundation" to logic would be a meta-logical theory, not the axioms/logical systems themselves. — schopenhauer1

Sure, if you like. Whether the binding between reality and logic is metalogical is largely dependent on how you conceive of logic. On my view something with no relation to reality (and therefore knowledge) is not logic. Ergo: something without that binding is not logic. It is just the symbol manipulation that Banno mistakes for logic. More precisely, it is metamathematics.

When you want to call the binding metalogical that makes me think that you take logic to be something that is not necessarily bound to reality in any way at all. What I would grant is that it is a somehow different part of logic, but I do not think that these parts are as easily distinguishable as the modern mind supposes. -

schopenhauer1

11kSure, if you like. Whether the binding between reality and logic is metalogical is largely dependent on how you conceive of logic. — Leontiskos

schopenhauer1

11kSure, if you like. Whether the binding between reality and logic is metalogical is largely dependent on how you conceive of logic. — Leontiskos

Glad we are on a philosophy forum and can adjust to the big picture and zoom in where necessary (and not stay in the weeds unnecessarily because- logic) then! :wink:.

On my view something with no relation to reality (and therefore knowledge) is not logic. Ergo: something without that binding is not logic. It is just the symbol manipulation that Banno mistakes for logic. More precisely, it is metamathematics. — Leontiskos

Nice idea. So for your understanding here you are saying that different mathematics are basically "arbitrary" forms of logic (that sometimes map to reality)? And then of course, my main question is "what is/how is it mapping to reality?"

When you want to call the binding metalogical that makes me think that you take logic to be something that is not necessarily bound to reality in any way at all. What I would grant is that it is a somehow different part of logic, but I do not think that these parts are as easily distinguishable as the modern mind supposes. — Leontiskos

I'm unclear what you are saying here...

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum