-

Michael

16.9k

Michael

16.9k

If by "the lemon is sour" you just mean "[tasting] the lemon will cause a sour-type mental percept" then I agree.

But if by "the lemon is sour" you mean "a sour taste is a mind-independent property of the lemon" then I disagree. This is the naive view that is inconsistent with the science of perception. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

And being sour is a property of lemons...Because a sour taste is a mental percept — Michael

We don't generally have the "mental percept" of "sour" in the absence of lemons or some other such food. But you talk as if there were nothing going on here that was not "mental". And indeed, that's perhaps what you are thinking. But it's muddled. Lemons are not "mental phenomena".

So rather than us having to guess what you think is going on, set it out for us all. Are there lemons? Or are there only the oxymoronic "mental phenomena"? -

Michael

16.9kAnd being sour is a property of lemons... — Banno

Michael

16.9kAnd being sour is a property of lemons... — Banno

As an adjective, yes, where this means that eating a lemon will elicit a sour-type mental percept.

We don't generally have the "mental percept" of "sour" in the absence of lemons or some other such food. — Banno

Well I do. My dreams and hallucinations aren't only visual and auditory; I smell and taste and feel.

So rather than us having to guess what you think is going on, set it out for us all. — Banno

I have done. Colours, smells, tastes, etc. are types of mental percepts, caused by neural activity in the appropriate cortexes in the brain. When this activity occurs when I'm asleep I'm dreaming. When this activity occurs when I'm awake, but in response to LSD, I'm hallucinating. When this activity occurs when I'm awake, and in response to ordinary external stimulation such as 700nm light reaching my eyes, I'm having a non-hallucinatory waking experience.

The naive view that then projects these mental percepts out into the wider world as mind-independent properties of things is mistaken. -

Banno

30.6kThe naive view that then projects these mental percepts out into the wider world as mind-independent properties of things is mistaken. — Michael

Banno

30.6kThe naive view that then projects these mental percepts out into the wider world as mind-independent properties of things is mistaken. — Michael

For the - I think seventh or eighth time - the claim is not that being red or sour or smooth is in no part mental, but that it is not exclusively in your mind alone. Hence the answer to

is "yes".Does the color “red” exist outside of the subjective mind that conceptually designates the concept of “red?” — Mp202020 -

Michael

16.9kFor the - I think seventh or eighth time - the claim is not that being red or sour or smooth is in no part mental, but that it is not exclusively in your mind alone. — Banno

Michael

16.9kFor the - I think seventh or eighth time - the claim is not that being red or sour or smooth is in no part mental, but that it is not exclusively in your mind alone. — Banno

And, yet again, I accept that the apple is red, where "red" is an adjective and "the apple is red" means something like "the apple is causally responsible for a red visual percept".

But as a noun, colours are only mental percepts, because when I use the word "colour" I am referring to a mental percept and a mental percept is only a mental percept. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

... if red is only a mental percept, then when you say “red” it refers to your mental percept, but when I say "red" it refers to my a mental percept. If we are going to be talking about the same thing then we need something that we both have access to. Hence there is more to being red than being a a mental percept.

That involves red things, in a world we have in common. -

Michael

16.9k... if "red" is only a mental percept, then when you say “red” it refers to your mental percept, but when I say "red" it refers to my a mental percept. — Banno

Michael

16.9k... if "red" is only a mental percept, then when you say “red” it refers to your mental percept, but when I say "red" it refers to my a mental percept. — Banno

How do you infer that? Pain is a mental percept, but when I use the word "pain" I am not referring only to my pain, just as when I use the words "thoughts" and "beliefs" I am not referring only to my thoughts and beliefs. I can refer to someone else's red just as easily as I can refer to someone else's pain and thoughts and beliefs.

It's true that I can't see their red or feel their pain or think their thoughts or believe their beliefs, but I can talk about them just fine. -

Michael

16.9kMaybe this will make my position clearer:

Michael

16.9kMaybe this will make my position clearer:

1. Colour percepts exist. They are what constitute (coloured) dreams and hallucinations.

2. These colour percepts also exist when awake and not hallucinating, e.g. when there is neural activity in the visual cortex in response to optical simulation by light.

3. When we ordinarily talk about colours we are, knowingly or not, referring to these colour percepts. -

Michael

16.9kI always have. I just deny that colours are something other than mental percepts, just as I deny that pain is something other than a mental percept.

Michael

16.9kI always have. I just deny that colours are something other than mental percepts, just as I deny that pain is something other than a mental percept.

There are mind-independent properties that are causally responsible for colour percepts in the ordinary waking case, e.g. having a surface layer of atoms that reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm, but the colour percept and this surface layer of atoms are distinct, dissimilar, things. And as nouns, the words "red" and "colour" ordinarily refer to these percepts. This is what allows variations in colour perception to be a coherent concept.

As adjectives, the words "red" and "coloured" can describe distal objects, but this just means that they are causally responsible for the related colour percepts in the ordinary waking case.

This view contrasts with the naive colour realist who believes that as nouns the words "red" and "colour" refer to some mind-independent property that resembles the colour percept, and who often denies the existence of the colour percept entirely. This naive colour realism is inconsistent with physics and the neuroscience of perception. -

jorndoe

4.2kI'd start with some, let's say, observations ...

jorndoe

4.2kI'd start with some, let's say, observations ...

• for hallucinations, imaginary/dream worlds, whatever, the perception and the perceived are the same

• when the perception and the perceived aren't the same, the perceived can be objects

• perceptions are events/processes, temporal, come and go, occur, are interruptible

• objects are spatial, left to right, front to back, movable, locatable, breakable under conservation

• by interaction one can perceive something without becoming the perceived in part or whole

... and take it from there.

(maybe I'm using the verbiage in a non-standard way)

I'm seeing some openings for category mistakes, perhaps depending on verbiage.

Red could be called one format of perception, typically related to objects we hence call red.

Or something like that.

Has synesthesia come up? Phantom pain? Mary's room? :) -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

the apple is red" means something like "the apple is causally responsible for a red visual percept".

Reminds me of the opening of Lewis's Abolition of Man.

In their second chapter Gaius and Titius quote the well-known story of Coleridge at the waterfall. You remember that there were two tourists present: that one called it 'sublime' and the other 'pretty'; and that Coleridge mentally endorsed the first judgement and rejected the second with disgust. Gaius and Titius comment as follows: 'When the man said This is sublime, he appeared to be making a remark about the waterfall... Actually ... he was not making a remark about the waterfall, but a remark about his own feelings. What he was saying was really I have feelings associated in my mind with the word "Sublime", or shortly, I have sublime feelings' Here are a good many deep questions settled in a pretty summary fashion. But the authors are not yet finished. They add: 'This confusion is continually present in language as we use it. We appear to be saying something very important about something: and actually we are only saying something about our own feelings.'1

Before considering the issues really raised by this momentous little paragraph (designed, you will remember, for 'the upper forms of schools') we must eliminate

one mere confusion into which Gaius and Titius have fallen. Even on their own view—on any conceivable view—the man who says This is sublime cannot mean I

have sublime feelings. Even if it were granted that such qualities as sublimity were simply and solely projected into things from our own emotions, yet the emotions

which prompt the projection are the correlatives, and therefore almost the opposites, of the qualities projected. The feelings which make a man call an object sublime are not sublime feelings but feelings of veneration. If This is sublime is to be reduced at all to a statement about the speaker's feelings, the proper translation would be I have humble feelings. If the view held by Gaius and Titius were

consistently applied it would lead to obvious absurdities. It would force them to maintain that You are contemptible means I have contemptible feelings', in fact that Your feelings are contemptible means My feelings are contemptible...

...until quite modern times all teachers and even all men believed the universe to be such that certain emotional reactions on our part could be either congruous or incongruous to it—believed, in fact, that objects did not merely receive, but could merit, our approval or disapproval, our reverence or our contempt. The reason why Coleridge agreed with the tourist who called the cataract sublime and disagreed with the one who called it pretty was of course that he believed inanimate nature to be such that certain responses could be more 'just' or 'ordinate' or 'appropriate'to it than others. And he believed (correctly) that the tourists thought the same.The man who called the cataract sublime was not intending simply to describe his own emotions about it: he was also claiming that the object was one which merited those emotions. But for this claim there would be nothing to agree or disagree about. To disagree with "This is pretty" if those words simply described the lady's feelings, would be absurd: if she had said "I feel sick" Coleridge would hardly have replied "No; I feel quite well." When Shelley, having compared the human sensibility to an Aeolian lyre, goes on to add that it differs from a lyre in having a power of 'internal adjustment' whereby it can 'accommodate its chords to the motions of that which strikes them', 9 he is assuming the same belief. 'Can you be righteous', asks Traherne, 'unless you be just in rendering to things their due esteem? All things were made to be yours and you were made to prize them according to their value.'10

But of course the larger point is about the "bloated subject," to which all the contents of the world are displaced. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

No, I think I get it. You said that movies cannot be funny, the lemons are not sour, and that apples cannot be red. Presumably waterfalls cannot be sublime, sunsets beautiful, noises shrill, voices deep, etc. This is precisely what Lewis is talking about.

I just don't think this separation makes any sense. Nor does it make sense to talk of such things as sourness or beauty existing exclusively in brains. Pace your appeal to "science," the science of perception does not exclude lemons from an explanation of why lemons taste sour or apples from the experience of seeing a red apple. These objects are involved in these perceptions; the perceptions would not exist without the objects.

Brains do not generate experiences on their own. If you move a brain into the vast majority of environments that exist in the universe, onto the surface of a star, the bottom of the ocean, the void of space, or anywhere outside a body, it will produce no experiences. Experience only emerges from brains in properly functioning bodies in a narrow range of environments and abstracting the environment away so as to locate these physical processes solely "in" brains or "brain states," is simply bad reasoning.

Science has nothing to do with it. It's projecting the foibles of modern philosophy onto science.

The key insight of phenomenology is that the modern interpretation of knowledge as a relation between consciousness as a self-contained ‘subject’ and reality as an ‘object’ extrinsic to it is incoherent. On the one hand, consciousness is always and essentially the awareness of something, and is thus always already together with being. On the other hand, if ‘being’ is to mean anything at all, it can only mean that which is phenomenal, that which is so to speak ‘there’ for awareness, and thus always already belongs to consciousness. Consciousness is the grasping of being; being is what is grasped by consciousness. The phenomenological term for the first of these observations is ‘intentionality;’ for the second, ‘givenness.’ “The mind is a moment to the world and the things in it; the mind is essentially correlated with its objects. The mind is essentially intentional. There is no ‘problem of knowledge’ or ‘problem of the external world,’ there is no problem about how we get to ‘extramental’ reality, because the mind should never be separated from reality from the beginning. Mind and being are moments to each other; they are not pieces that can be segmented out of the whole to which they belong.”* Intended as an exposition of Husserlian phenomenology, these words hold true for the entire classical tradition from Parmenides to Aquinas.

Eric Perl - Thinking Being -

jkop

1kSo not like dawn or dusk? — apokrisis

jkop

1kSo not like dawn or dusk? — apokrisis

Sorry for late reply, I'm travelling.

At dawn or dusk, a red coin may appear unsaturated, perhaps blended with other colours from the sky etc. That's what its red colour looks like under weak, blended light conditions. Moreover, its circular shape appears oval, or rectangular even, depending on the angle of view.

From these variations it doesn't follow that the red and the circular are figments of the mind, neurological processes, or conventions of language.

From a neuroscience view, the point of colour vision is not because the world is coloured. — apokrisis

Colours might seem insignificant in neuroscience, or conventions in fashion, but that's not a failure to be real in biology.

Colour vision is an adaption to way the physical world is. -

frank

19kNo, I think I get it. You said that movies cannot be funny, the lemons are not sour, and that apples cannot be red. Presumably waterfalls cannot be sublime, sunsets beautiful, noises shrill, voices deep, etc. This is precisely what Lewis is talking about.

frank

19kNo, I think I get it. You said that movies cannot be funny, the lemons are not sour, and that apples cannot be red. Presumably waterfalls cannot be sublime, sunsets beautiful, noises shrill, voices deep, etc. This is precisely what Lewis is talking about.

I just don't think this separation makes any sense. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Sorry to butt in, but I think if you're approaching this from ordinary language, you should keep in mind that languages vary in how they express the relationship between objects and their properties. In English it's pretty common to apparently directly equate them, as when we say the tea is cold. But in other languages, it would be that the tea has coldness, or that the coldness is upon the tea. It's native to English to treat properties as transient and objects as permanent, but that just doesn't show up as overtly as, say, in Spanish.

Experience only emerges from brains in properly functioning bodies in a narrow range of environments and abstracting the environment away so as to locate these physical processes solely "in" brains or "brain states," is simply bad reasoning. — Count Timothy von Icarus

What about the experiences of people on say, ketamine? Their experiences are in some way "in the language" of earthly life, but they're definitely not reflecting anything in the person's environment. Those experiences appear to be created by the brain alone. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

In English it's pretty common to apparently directly equate them, as when we say the tea is cold. But in other languages, it would be that the tea has coldness, or that the coldness is upon the tea

I am not t sure how these are supposed to be counter examples. They still ascribe the property to the thing. Is there a language that does not ascribe color, heat, tone, or taste to things but only to subjects? I am not aware of one.

What about the experiences of people on say, ketamine? Their experiences are in some way "in the language" of earthly life, but they're definitely not reflecting anything in the person's environment. Those experiences appear to be created by the brain alone.

These experiences simply aren't created by the "brain alone."

What experiences will someone on ketamine have if they are instantly teleported to the bottom of the sea, the void of space, or the surface of a star? Little to none, their body and brain will be destroyed virtually instantly in the first and last case. The enviornment always matters.

Less extreme, imagine if we suck all that air out of the room. Will the person's experience remain the same? Obviously not, having access to air is part of their experience. Or suppose the building they are in collapses and a support beam runs through their chest but their brain is left pretty much unharmed? Same thing. Without the body and the enviornment the brain cannot produce experiences.

The brain doesn't produce experience "on its own," or "alone." Producing experience requires a constant flow of information, causation, matter, and energy across the boundaries of the brain and body. It only seems to act "alone" when we abstract away an environment that we have held constant within a precise ranges of values. A human body dies very quickly in the overwhelming majority of environments that prevail in our universe, there are very few where it continues to produce experience for even a few minutes (and this still requires the whole body, not just the brain). -

Count Timothy von Icarus

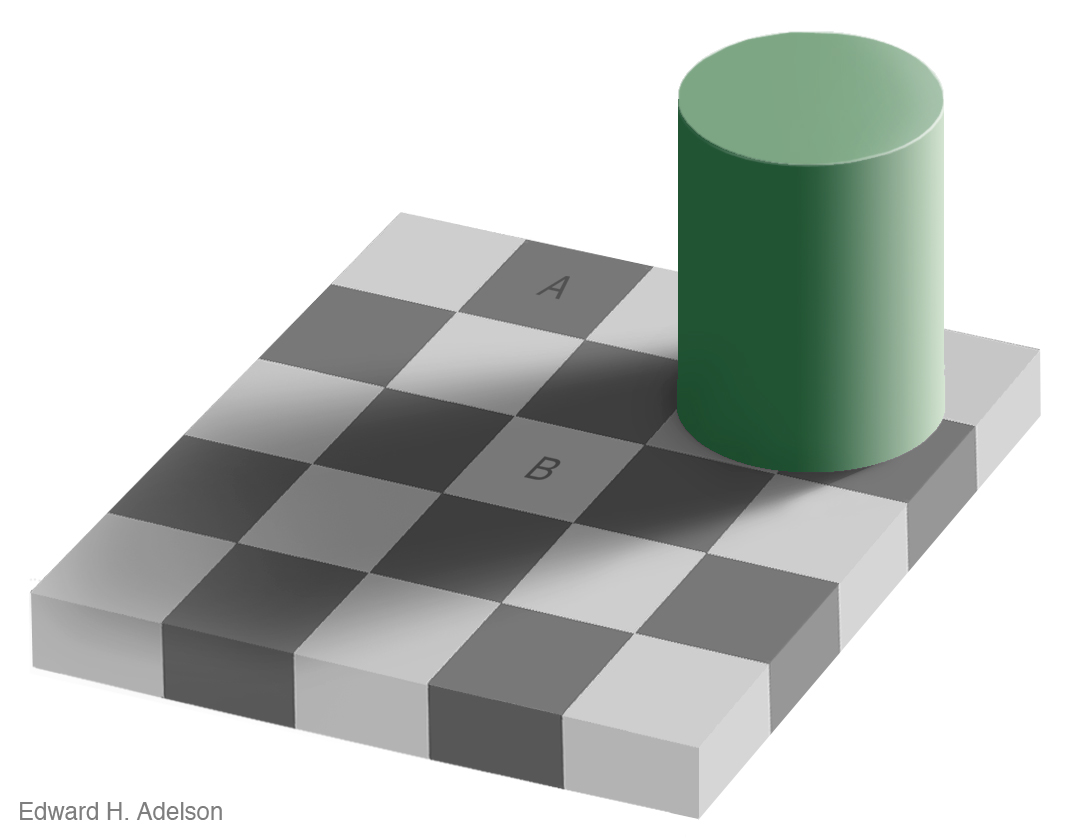

4.3kConsider this famous optical illusion.

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kConsider this famous optical illusion.

The "big reveal" is that both labeled squares are "the same shade of gray." I have had students refuse to believe this until I snip out one square and put it next to the other.

Of course, this is generally presented as the squares themselves being "the same color." You can confirm this by looking at the hex codes of the pixels that make them up.However, on an account where grayness, shade, hue, brightness, etc. are all purely internal and "exist only as we experience them," it seems hard to explain the illusion. If the shades of gray appear different, and color just is "how things appear to us," in what sense are the two squares the "same color gray?" It seems that their color should rather change with their context. -

Michael

16.9kYou said that movies cannot be funny, the lemons are not sour, and that apples cannot be red. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Michael

16.9kYou said that movies cannot be funny, the lemons are not sour, and that apples cannot be red. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I clarified what I meant in that aforementioned post.

The nouns "sour" and "red" refer to mental percepts – those things that also exist when we dream, hallucinate, have synesthesia, and so on, and which explain differences in perception.

The adjectives "sour" and "red" when predicated of lemons and apples describe the fact that they are causally responsible for the associated mental percept in ordinary waking situations.

So apples are red and lemons are sour.

But this doesn't mean that redness and sourness are mind-independent properties of apples and lemons as the naive realist believes.

Pace your appeal to "science," the science of perception does not exclude lemons from an explanation of why lemons taste sour or apples from the experience of seeing a red apple. These objects are involved in these perceptions; the perceptions would not exist without the objects. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Their involvement is causal, nothing more. The window wouldn't have broken if the football had not been kicked through it, but the broken window is not a property of the football. And the sour-taste mental percept would not be present if I had not eaten the lemon, but the sour-taste mental percept is not a property of the lemon (and nor does it resemble any of the lemon's properties).

How exactly does your account even allow for the coherence of dreams, hallucinations, synesthesia, and difference in colour perception, let alone their facticity? -

frank

19kIn English it's pretty common to apparently directly equate them, as when we say the tea is cold. But in other languages, it would be that the tea has coldness, or that the coldness is upon the tea

frank

19kIn English it's pretty common to apparently directly equate them, as when we say the tea is cold. But in other languages, it would be that the tea has coldness, or that the coldness is upon the tea

I am not t sure how these are supposed to be counter examples. They still ascribe the property to the thing. Is there a language that does not ascribe color, heat, tone, or taste to things but only to subjects? I am not aware of one. — Count Timothy von Icarus

They describe a relationship between the property and the thing. That allows us talk about a property like redness as something separate from an object. When we notice that the red apple is black under a red light, we realize that this property belongs to the whole setting that includes the object. And it turns out that the story of redness also includes functions of consciousness and experience. I think you were touching on that with the Perl quote, that it appears that experience is a holistic symphony that we subsequently analyze, dissect, placing the pieces on a table like a dismantled clock.

The danger here is to take pieces of the dismantled clock and imagine that we're grasping a firm foundation from which to philosophize. As long as we remember that, we can divide the symphony up however we like. It's legit to concentrate on experience itself. That's what a large chunk of phenomenology is doing. Experience is what we know directly. All else is dubious. It's one way to approach the issue, right?

What experiences will someone on ketamine have if they are instantly teleported to the bottom of the sea, the void of space, or the surface of a star? Little to none, their body and brain will be destroyed virtually instantly in the first and last case. The environment always matters. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Right. If John is dead, John won't be experiencing anything. Does this mean we can't talk about the experiences John's brain creates while he's still with us?

Or suppose the building they are in collapses and a support beam runs through their chest but their brain is left pretty much unharmed? Same thing. Without the body and the enviornment the brain cannot produce experiences — Count Timothy von Icarus

We'll rush John to the hospital and put him on ECMO. He actually doesn't need a heart, lungs, or kidneys now. We'll provide a kind of IV feed so he doesn't need a digestive system. We'll just float his nervous system in a gel. We don't do this because it would just be a short term horror movie, but we could. And the brain would create experiences because that's just what it does. It doesn't need anything from the outside.

The brain doesn't produce experience "on its own," or "alone." Producing experience requires a constant flow of information, causation, matter, and energy across the boundaries of the brain and body. — Count Timothy von Icarus

That's not true. You don't need a body, as previously described. -

Michael

16.9kOf course, this is generally presented as the squares themselves being "the same color." You can confirm this by looking at the hex codes of the pixels that make them up.However, on an account where grayness, shade, hue, brightness, etc. are all purely internal and "exist only as we experience them," it seems hard to explain the illusion. If the shades of gray appear different, and color just is "how things appear to us," in what sense are the two squares the "same color gray?" It seems that their color should rather change with their context. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Michael

16.9kOf course, this is generally presented as the squares themselves being "the same color." You can confirm this by looking at the hex codes of the pixels that make them up.However, on an account where grayness, shade, hue, brightness, etc. are all purely internal and "exist only as we experience them," it seems hard to explain the illusion. If the shades of gray appear different, and color just is "how things appear to us," in what sense are the two squares the "same color gray?" It seems that their color should rather change with their context. — Count Timothy von Icarus

They emit the same wavelength of light, but produce different colour percepts. It's the same principle involved with the photo of the dress.

Colour terms like "grey", "black", "blue", "white", and "gold" are then used in at least two different ways, either referring to the fact that they emit the same frequency of light ("the squares are the same shade of grey") or to the fact that they produce different colour percepts ("I see white and gold; she sees black and blue").

The use of such terms to refer to the fact that they emit the same frequency of light is something of a fiction, premised on the misguided naive realist view that treats colour percepts as being mind-independent properties (or, at the very least, the misguided view that colour percepts "resemble" in some sense mind-independent properties). -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Does this mean we can't talk about the experiences John's brain creates while he's still with us?

No, it means we can't talk about the "brain alone," creating experience.

You'll note that in all your counter examples, e.g. the beam falling on John, you have concocted wild changes to the enviornment, not the brain, in order to sustain the possibility of conciousness, which gives lie to the "brain alone" explanation.

So I'll ask again, show me a brain alone producing conciousness. No enviornment. Your examples all involve radically altering the enviornment so as to have it preform the functions of the body, which is not a counter example. -

frank

19k

frank

19k

The point was that you don't need a biological body. In the case of the supporting apparatus, it would be right to say it's necessary for the life of the brain. It's providing the brain's power source. It's not part of what the brain is doing, though. If you think it is, how? How is it part of consciousness? -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

It's perhaps possible to have experiences while replacing a large part of the body with some sort of system that does functionally the same things as the body. But presumably you could also replace parts of the brain with synthetic components in a similar manner. Shall we abstract that away as well?

None of your examples prove that brains can generate experiences "all by themselves." All you do in your examples is substitute parts of the enviornment for functional equivalents. This is not the same thing as the enviornment being irrelevant to or uninvolved in the generation of experience. Indeed, the fact that you have to posit very specific environmental changes in order to preserve the possibility of there being any conciousness at all gives lie to the idea of the "brain alone" producing experience in a vacuum.

Not to mention that it seems uncontroversial that, in actuality, no brain outside a body has ever maintained conciousness. If one is to invoke "the science of perception," in any sort of a realist sense then it seems obvious that lemons are involved in lemons' tasting sour, apples are involved in apples' appearing red, etc. We can speculate all we want about sci-fi technology approaching sorcery (which is what "the Matrix" or a "brain in a vat" is), but this is to follow modern philosophy's pernicious elevation of potency over act in all of its analysis.

It would be more accurate to say that "physical systems give rise to experience" and that these physical systems always and necessarily involve both body and the environment. Truly isolated systems don't exist in nature and the brain couldn't maintain conciousness even if it was magically sequestered in its own universe.

At any rate, when something looks rectangular or big, this is because of interactions between the object, ambient light, and the body; it's the same with color. Color is susceptible to optical illusions, sure, but so to is size, motion, and shape. I have yet to see a good argument why color is "mental precept" all the way down, but presumably shape and size are not.

I am not sure what motivates Michael's response that shape, motion, and size should be seen as "properties of objects themselves," because this is suggested by "the Standard Model." I would assume the assumptions here are reductionist and smallist, since this is normally why people come to the old "primary versus secondary qualities," style distinctions and end up involving particle physics to make a case vis-á-vis perception. I don't think there is good evidence for assuming that reductionism is true until proven otherwise. 100+ years on and even the basics of chemistry like molecular structure have not be successfully reduced to physics. -

Kizzy

165

Kizzy

165

Magically sequestered! Ha, I like that! I picture a more vibrant experience for IT...maybe one not so alone, perhaps? What do I know?Truly isolated systems don't exist in nature and the brain couldn't maintain conciousness even if it was magically sequestered in its own universe. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Did the movie SIXTH SENSE destroy the myth that perception is absolute reality?

- What is the Difference Between Dream and Waking Experience in the Perception of 'Reality'?

- Essay Number One: ‘Perceptions of Experience and Experiences of Perception’

- What Happens Between Sense Perception And When Critical Thought Kicks-In?

- Neural Networks, Perception & Direct Realism

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum