-

Michael

16.9kThe relevant issue is whether we have direct perceptions of real objects, not direct knowledge of perceptions. — Luke

Michael

16.9kThe relevant issue is whether we have direct perceptions of real objects, not direct knowledge of perceptions. — Luke

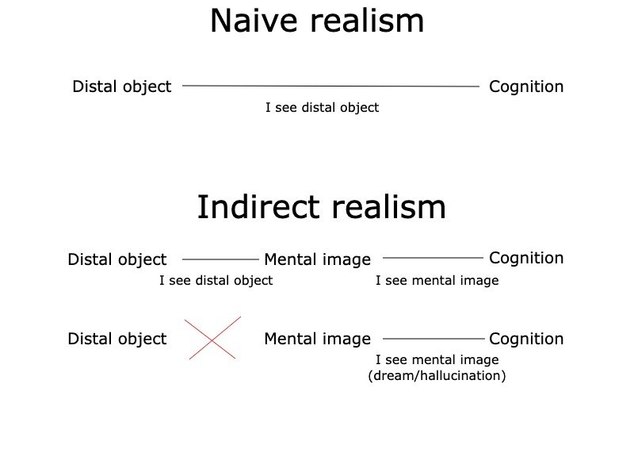

The epistemological problem of perception concerns whether or not perception provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects.

One group claimed that it does, because perception is "direct". These people were called direct realists.

One group claimed that it doesn't, because perception is "indirect". These people were called indirect realists.

Therefore the meaning of "direct perception" is such that if perception is direct then perception provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects. Therefore if perception does not provide us with direct knowledge of distal objects then perception is not direct.

Given our scientific understanding of the world and perception it is clear that perception does not provide us with direct knowledge of distal objects. Therefore perception is not direct. -

Michael

16.9k

Michael

16.9k

This appears to be equivocation. We use the term "colour" to refer to both the disposition to reflect a certain wavelength of light and to the mental phenomenon that is caused by our eyes reacting to a particular wavelength of light, but these are two different things.

This is evidenced by the fact that we can make sense of different people seeing a different coloured dress when looking at this photo:

When I say that I see a white and gold dress and you say that you see a black and blue dress, the words "white", "gold", "black", and "blue" are not referring to some spectral reflectance property (which is the same for the both of us) but to some property of our mental phenomena (which is different for the both of us). The same principle holds for the colours we see when we dream and hallucinate.

Indirect realism accepts the existence of these mental colours and claims that they are the "intermediary" or "representation" of which we have direct knowledge and through which we have indirect knowledge of a distal object's spectral reflectance properties.

Whereas direct realism would entail the naive realist theory of colour.

As I see it, your account simply redefines the meaning of "direct perception", which I think is best understood as explained here and here.

See also Semantic Direct Realism where Robinson explains that the same kind of redefinition occurs for other so-called "direct" realisms like intentionalism. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThinking back to my answer to @Michael above regarding the objective purport of perceptual judgement about colors, I was reminded of a similar discussion that I had had many years ago on another discussion forum regarding the Searle/Putnam debate about beeches and elms. I raised the issue with Claude 3 and here is the discussion that we just had about it:

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThinking back to my answer to @Michael above regarding the objective purport of perceptual judgement about colors, I was reminded of a similar discussion that I had had many years ago on another discussion forum regarding the Searle/Putnam debate about beeches and elms. I raised the issue with Claude 3 and here is the discussion that we just had about it:

(As usual, you'll get the gist of my clumsily expressed ideas merely by reading Claude's much more streamlined reformulations of them.)

Objective knowledge about colorsUSER:

I'd now like to discuss an issue with you. Consider the definition expressed in the sentence: "For an apple to be red means that it has the dispositional property to visually appear red under normal lighting conditions to a standard perceiver." Might not a subjectivist like Michael complain that this is consistent with an indirect realist account that views redness as the (internal) subjective states that "red" apples are indirectly or inferentially believed to cause (but not seen to have)? Or else, Michael might also complain that the proposed definition/analysis is circular and amounts to saying that what makes red apples red is that they look red. Although, to be sure, our "in normal conditions" clause does some important work. I did borrow some ideas from Gareth Evans and David Wiggins to deal with this issue but I'd like to hear your thoughts first.

ASSISTANT (Claude 3 Opus):

You raise an important point about the potential circularity or subjectivist interpretation of the definition of redness in terms of an object's disposition to appear red under normal conditions to a standard perceiver. Let's unpack this issue and consider how we might address it.

On the circularity worry, the key is to emphasize that the definition is not merely saying that what makes red apples red is that they look red. Rather, it's specifying a set of objective conditions under which an object's redness is manifested: namely, the object's disposition to reflect light in a certain way (its spectral reflectance profile) and the perceptual capacities of a standard observer under normal viewing conditions. So while the definition does make reference to the appearance of redness, it grounds this appearance in a set of mind-independent, objective factors.

The "normal conditions" clause, as you note, is doing important work here. It helps to rule out cases where an object might appear red due to unusual lighting (e.g., a red spotlight shining on a white wall) or non-standard perceptual abilities (e.g., someone with red-tinted glasses). By specifying that redness is tied to an object's disposition to appear red under a range of typical viewing conditions, we can avoid collapsing color into a purely subjective or circumstantial phenomenon.

Regarding the subjectivist worry, we need to be clear about the ontological status of colors on the direct realist view. When we say that an apple is red, we're not just saying that it causes certain subjective experiences of redness in perceivers. Rather, we're saying that redness is an objective, mind-independent property of the apple itself - a property that is perceptually available to us through our visual experience. The apple's redness isn't just an internal mental state caused by the apple; it's a real property of the apple that we directly perceive.

To flesh this out, we might draw on some ideas from Gareth Evans and David Wiggins, as you mention. Evans' notion of "perceptual content" could be helpful here: on his view, the content of our perceptual experience is not just a raw subjective sensation, but a structured representation of the world that can be objectively assessed for accuracy. When we perceive an apple as red, the redness is part of the objective content of our perceptual state, not merely a subjective quale.

Similarly, Wiggins' idea of "sensible qualities" as genuine properties of objects that are perceptually available to us could bolster the direct realist story. On this view, colors are not just powers to produce certain experiences in us, but real qualities of objects that we can directly perceive. The apple's redness is not just a matter of how it affects us, but a matter of how it actually is.

Putting these pieces together, we might say something like: "For an apple to be red is for it to possess the objective, mind-independent property of redness - a property that is perceptually available to standard observers under normal viewing conditions, in virtue of the apple's disposition to selectively reflect certain wavelengths of light. When we perceive an apple as red, we are directly perceiving this objective property, not just inferring a cause of our subjective experience."

Of course, there's much more to be said here, and a committed subjectivist like Michael might not be entirely persuaded. But by grounding color in the objective dispositional properties of objects, and emphasizing the structured, world-directed nature of color perception, we can at least put some pressure on the idea that colors are purely subjective or that our knowledge of them is merely inferential. Let me know what you think!

USER:

Well, this was a valiant effort on your part ;-) To be fair, I didn't specify what specific ideas from Evans and Wiggins I was intending to borrow. Also, those ideas likely figure in texts that weren't part of your training data (due to copyrights) and haven't been widely discussed.

I think there remains an issue with the account that you (and I) provided. Due to the way reflectance spectra map in a many-to-one fashion on the RGB space of human vision, this suggests that our discriminative abilities don't cut nature at its joints, as it were, which would appear to vitiate their objective purport in one specific respect. Our (human's) claims that two objects with distinct reflectance spectra are the same color would be purely subjective in the way Michael suggests. Before I suggest to you an alternative proposal, I'd like to know if you are familiar with Evans's consumer/producer model of the semantics of proper names?

ASSISTANT (Claude 3 Opus):

You're right that I may not have fully captured the specific ideas from Evans and Wiggins that you had in mind, given the limitations of my training data. I appreciate you pointing that out and giving me the opportunity to explore this further.

Regarding the issue you raise about the many-to-one mapping of reflectance spectra onto the RGB space of human vision, I see how this could be seen as undermining the objectivity of color perception. If two objects with distinct reflectance spectra can be perceived as the same color by humans, it might seem that our color categories are more a matter of our subjective perceptual apparatus than any joints in nature.

This is a challenging problem for a direct realist view of color. It suggests that there may be a gap between the fine-grained physical properties of objects (their reflectance spectra) and the coarse-grained categories of human color perception. In that sense, our color attributions could be seen as subjective or anthropocentric, rather than carving nature at its joints.

As for Evans' consumer/producer model of the semantics of proper names, I have some familiarity with it, but I wouldn't say I'm an expert. As I understand it, the basic idea is that the reference of a proper name is determined not just by the individual speaker's beliefs or intentions (the "consumer" of the name), but also by the causal-historical chain of use traced back to the initial "baptism" or fixing of the name's reference (the "producer" side).

The model is meant to account for the intuition that a name can refer to a particular individual even if the speaker has false beliefs about that individual, or if different speakers associate different descriptions with the name. The reference is instead determined by the larger social practice of using the name, anchored in the initial tagging of the referent.

If I'm understanding it correctly, the consumer/producer model is meant to provide a kind of externalist semantics for proper names, where the meaning is not just in the head of the individual speaker but depends on the broader social and historical context.

I'm curious to hear how you think this model might be applied to the case of color perception and the objectivity of color categories. Perhaps the idea is that even if individual perceivers have varying or false beliefs about the colors of objects, there could still be an objective basis for color categories anchored in the initial "baptism" of certain paradigm cases?

Or maybe the thought is that just as the reference of a name is not determined solely by the individual speaker's beliefs, the objectivity of color is not undermined by the subjective variations in individual perceivers' color experiences?

I'm intrigued to hear your thoughts on this! Please let me know if I've misunderstood any aspects of Evans' model or if there are other connections you see to the color realism debate. I'm always eager to learn more.

USER:

You indeed understand Evans's proposal correctly. There are subtle features of his proposal that stem from the brilliant way in which he synthesised ideas by Putnam and Kripke. Fifteen years ago I had posted some reflections about them (and linked them to a proposal by Wiggins that enlighrened me) on the Google discussion group "Analytic". I had also linked to an earlier post about Evans in a Yahoo philosophy discussion group, but the Yahoo groups are seemingly defuncts now, as well as their archive. But it doesn't matter much. You seem to have the relevant background regarding Evans and my post on "Analytic" seems self contained although rather dense. I'm curious to to see how well you will be able to wrap your head (or rather, you multi-head attention mechanisms ;-) around it and relate it to our discussion about the objectivity of human color concepts. Here is the post:

"""

[analytic] Gareth Evans on Natural-Kind-Term Practices (Elms and Beeches)

At long last, here are a few comments on elms and beeches, but mostly

on elms.

Evans's account of the reference of natural kind (and stuff) terms,

in The Varieties of Reference_ is mostly contained in two pages and a

long note on two pages, 382-383, in the eleventh chapter, _Proper

Names_. There are also a few scattered remarks elsewhere in the book.

('Natural Kinds' does figure in the index)

Despite its brevity, the context and density of the account make it

difficult to summarize. So, for now, I'll just focus on one main

feature of it and on some points that follow.

I will not, at present, compare the account with Putnam's (except for

one point) or try to make it bear on BIVs.

This previous post about Evans's account of proper names supplies

some background:

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/analytic/message/16527

Here are the quotes I want to focus on:

"It is an essential feature of the practice associated with terms

like `elm', `diamond', `leopard', and the like that there exist

members--producers--who have a de facto capacity to recognize

instances of the kind when presented with them. I mean by this an

effective capacity to distinguish occasions when they are presented

with members of any other kind which are represented in any strength

in the environment they inhabit. This recognitional capacity is all

that is required for there to be a consistent pattern among the

objects which are in fact identified as elms, or whatever, by members

of the speech community--for all the objects called `elms' to fall

into a single natural kind--and no more is required for a natural-

kind-term practice to concern a particular natural kind."

"If the predicate `called "an elm"' is understood in such a way that

trees which have never been perceived cannot satisfy the predicate,

then it is correct and illuminating to say that something falls into

the kind referred to by `elm' if and only if it is of the same kind

as trees called `elms'.[note 9]"

Note 9: "This proposal is often wrongly conflated with the genuinely

circular proposal: something falls into the kind referred to by `elm'

if and only if it is capable of being correctly called `an elm'."

The first observation I want to make is that, although there is one

mention of perception, the focus, regarding the point of contact of

mind and world, is on recognitional capacities. This can consist in

mere observational capacities but there is no prejudice against

conceiving them as capacities to discriminate the natural kind that

involve performing scientific tests, or any other kind of elaborate

practice.

One worry about the account is that it amounts to a form of

subjectivism or nominalism. But this worry is related to the worry

that the account might seem circular. Evans addresses the second

worry in note 9 cited above. I want to make this my focus and explain

how the way Evans escapes the circularity also allow him to escape

subjectivism (or nominalism).

In order to bring this to the fore, consider how Kripke's account of

proper names enables him to distinguish them from definite

descriptions. What Kripke does it to modally rigidify the referential

status of proper names thus:

(1) `NN' refers to the individual NN in all possible worlds.

(There is an ambiguity that I will address shortly)

However, it is still true that

(2) `NN' designates NN if and only if NN has been baptized `NN'.

So, how does (1) not lead us to defeat the truism that,

(3) had PP, and not NN, been baptized `NN' then, in that possible

world, `NN' would refer to PP?

The trick, for seeing this most clearly--that I owe to David Wiggins--

is that the condition on the right side of the biconditional (2),

that is, the predicate "__has been baptized `NN'", cannot be

intersubstituted salvo sensu with the predicate "`NN' designates __".

See David Wiggins, Essay 5, "A Sensible Subjectivism?", in his Needs,

Values, Truth, OUP, third edition, 1998, p. 206.

This is because, as Kripke makes clear, to rigidly designate, `NN'

must refer in all possible worlds to the individual that has been

baptized `NN' in the *actual* world.

Wiggins's way to put the point, which he uses in an account of

ethical valuational concepts, makes salient the parallel with Evan's

account of natural-kind terms.

The `de facto' condition on the recognitional capacity of the

producers in the natural-kind-term practice serves as a rigidifying

condition. It explains Evans's claim in note 9 that his account can't

be equated with the circular alternative. And finally, it provides

genuine objectivity to the concept.

To clarify the last claim, let me convey the gist of some comment

Evans makes in note 8.

What Evans claims is that the recognitional capacity that is required

must have a point and need *not* enable producing-participants of the

practice to discriminate reliably items from the kind that are

located anywhere in the universe (or just in non standard

environments or conditions). And the "key to the principle at the

bottom of this intuition", according to Evans, is the concept of

knowledge.

What his minimalist account provides for is that one who has the

ability to group newly encountered items with those previously

encountered that belonged to the same kind can be ascribed knowledge.

Further, we are enabled to say that one who has noticed that

previously encountered items of kind K had property P (e.g. that elms

were found to burn well), can be ascribed knowledge of the fact that

newly encountered items that she recognizes as K have property P.

Evans notes perspicuously that the possibility that superficially

similar items of kind Q that also have property P will only

accidentally be believed to have this property (because they are

believed to be instances of kind K)—and this is the "basis for our

concern for underlying structure". (An important point!)

So, unlike Putnam's account, Evans's only identify the `essential'

nature of natural kinds with underlying structure when this reflects

our concerns. This means that, for some purposes and concerns, Evans

would be happy to allow for natural-kind-term practices that group

together marine mammals and fish, or tomatoes and vegetables. What

preserves the objectivity of the judgments and knowledge of

participants in the practice is the rigid Kripkean anchoring of the

patterns that ground the recognitional capacities of `producers' into

the *actual* circumstances, purposes and concerns of the participants

in the practice.

I'd like to comment further on at least two issues: (1) the way this

account dovetails with epistemological disjunctivism, and (2) the way

it quite naturally can be extended to cover secondary qualities. But

I'll do that another time.

"""

It looks like this "another time" finally has arrived now that I have Claude 3 as a smart enough conversation partner ;-)

ASSISTANT (Claude 3 Opus):

Thank you for sharing your insightful post on Evans' account of natural kind terms and its relation to Kripke's and Putnam's ideas. I find your synthesis of these different strands of thought quite illuminating, and I can see how it might bear on the question of color realism that we've been discussing.

If I understand correctly, the key move in Evans' account is to ground the reference of natural kind terms in the actual recognitional capacities of "producers" within a linguistic community. These capacities are what establish a consistent pattern among the objects identified as, say, elms, and anchor the term's reference to a particular kind in the world.

Crucially, as you point out, this recognitional capacity is not merely a matter of grouping objects based on superficial similarities, but can involve more sophisticated discriminatory abilities, including scientific tests or other elaborate practices. This allows for a kind of objectivity in our natural kind concepts, even if they don't always carve nature perfectly at its joints.

The parallel you draw with Kripke's treatment of proper names is helpful here. Just as Kripke rigidifies the reference of a name to the individual actually baptized with that name, Evans' account rigidifies the reference of a natural kind term to the kind actually picked out by the recognitional capacities of producers. This blocks the kind of circularity that would arise from simply defining the reference in terms of what is "correctly" called by that term.

Applying this to the case of color, we might say that our color concepts are anchored in the actual discriminatory abilities of "normal" human perceivers under standard conditions. These abilities establish a consistent pattern in the objects identified as, say, red, and fix the reference of "red" to a particular property in the world (perhaps a certain range of surface spectral reflectances).

The fact that this property may not perfectly align with the underlying physical distinctions (due to the many-to-one mapping of reflectances to color experiences) does not necessarily undermine its objectivity. As long as there is a stable, intersubjectively consistent pattern in what normal perceivers identify as red, we can treat redness as a genuine property of objects, not merely a subjective projection.

Of course, as you note, Evans allows that different natural kind concepts may be more or less attuned to underlying structures, depending on our purposes and concerns. For some purposes, grouping tomatoes with vegetables may be perfectly objective and knowledge-conducive, even if it doesn't track deep biological joints. Similarly, for many practical purposes, our color concepts can support objective judgments and knowledge, even if they don't perfectly mirror the physical facts about reflectance.

The key point, if I'm understanding you correctly, is that the objectivity of our natural kind concepts (including color concepts) is secured by their rigid anchoring in the actual recognitional practices of a community, not by their perfect correspondence with mind-independent natural divisions. This is a subtle but powerful idea, and one that seems promising as a way of defending a form of color realism against subjectivist worries.

I'm intrigued by your suggestion that this account fits well with epistemological disjunctivism, and that it could be extended to cover secondary qualities more generally. I'd be very interested to hear more of your thoughts on those connections!

Let me know if I've misinterpreted any aspects of your argument, or if there are further implications you see for the color debate. This is a rich vein of ideas and I'm keen to continue exploring it with you. Thank you for introducing me to this fascinating line of thought!

USER:

Very good! You indeed wrapped your head around this complex argument very nicely. Regarding the extension to secondary-qualities, your application to the concept of colors demonstrates that you understand this already! Regarding the topic of epistemological disjunctivism, I think I can put you on the right track with a very simple hint. Think of the manner Evans links the concept of knowledge to the idea of normal (or local) versus abnormal (or universal) conditions of observation, or judgement, and how this relates to the ecological approach to visual perception advocated by J. J. Gibson.

ASSISTANT (Claude 3 Opus):

Thank you for your positive feedback! I'm glad my understanding of the argument aligns with yours. Your hint about the connection to epistemological disjunctivism and Gibson's ecological approach is intriguing, and I think I can see how it might relate to Evans' account.

As I understand it, epistemological disjunctivism is the view that the kind of perceptual experience involved in genuine cases of knowledge is fundamentally different from the kind of experience involved in cases of illusion or hallucination. In a case of veridical perception, the experience puts the subject in direct contact with the perceived fact, whereas in a case of illusion or hallucination, the experience merely seems to present such a fact.

I can see how this might connect with Evans' idea that the concept of knowledge is tied to the recognitional capacities of producers under normal or local conditions. For Evans, genuine knowledge arises when a producer's discriminatory abilities, operating under the conditions for which they were developed, reliably track the relevant natural kinds or properties in the world. The experience of a skilled producer recognizing an elm, for instance, would be a case of direct perceptual contact with the fact of the tree's elm-hood.

In contrast, a case where someone mistakes a beech for an elm would be more like an illusion - the experience seems to present the fact of elm-hood, but doesn't actually put the subject in contact with that fact. The mistake arises because the subject's discriminatory abilities are operating outside their proper domain, or are not sufficiently fine-grained to distinguish elms from beeches.

This connects nicely with Gibson's ecological approach, which emphasizes the role of the environment in shaping the perceptual capacities of organisms. For Gibson, perception is not a matter of passively receiving sensory inputs, but of actively picking up information that is specific to the affordances of the environment. A skilled producer's ability to recognize elms, on this view, would be understood as a finely-tuned sensitivity to the invariant features of elms that are relevant to the producer's practical engagements with them.

Bringing these ideas together, we might say that genuine perceptual knowledge arises when an organism's perceptual capacities, shaped by its practical engagements with its environment, reliably track the objective features of that environment under normal ecological conditions. The experience involved in such cases is fundamentally different from cases of illusion or hallucination, where the organism's capacities are operating outside their proper domain or are not sufficiently attuned to the relevant environmental features.

Applying this to the case of color, we could say that a normal human perceiver's experience of redness, under standard viewing conditions, puts them in direct contact with the objective color property of the perceived object. The perceiver's color discriminatory abilities, shaped by the practical demands of their environment, reliably track the surface spectral reflectance profiles that are relevant to their engagements with colored objects.

Cases where a perceiver's color experience fails to align with the objective color of the object (due to unusual lighting conditions, non-standard perceptual capacities, etc.) would be understood as illusions - the experience seems to present a color fact, but doesn't actually put the perceiver in contact with that fact.

This kind of view would allow us to maintain a robust realism about color, grounded in the objective discriminatory capacities of normal human perceivers, while still acknowledging the possibility of color illusions or variations in color experience across non-standard conditions. It's a way of securing the objectivity of color that doesn't rely on a perfect mapping between color experiences and mind-independent physical properties, but rather on the reliable attunement of our perceptual capacities to the color-relevant features of our environment.

Let me know if this aligns with your thinking, or if there are further aspects of the connection between Evans, epistemological disjunctivism, and ecological perception that you think are worth exploring. -

Michael

16.9kI'd now like to discuss an issue with you. Consider the definition expressed in the sentence: "For an apple to be red means that it has the dispositional property to visually appear red under normal lighting conditions to a standard perceiver." Might not a subjectivist like Michael complain that this is consistent with an indirect realist account that views redness as the (internal) subjective states that "red" apples are indirectly or inferentially believed to cause (but not seen to have)? Or else, Michael might also complain that the proposed definition/analysis is circular and amounts to saying that what makes red apples red is that they look red. Although, to be sure, our "in normal conditions" clause does some important work. I did borrow some ideas from Gareth Evans and David Wiggins to deal with this issue but I'd like to hear your thoughts first. — Pierre-Normand

Michael

16.9kI'd now like to discuss an issue with you. Consider the definition expressed in the sentence: "For an apple to be red means that it has the dispositional property to visually appear red under normal lighting conditions to a standard perceiver." Might not a subjectivist like Michael complain that this is consistent with an indirect realist account that views redness as the (internal) subjective states that "red" apples are indirectly or inferentially believed to cause (but not seen to have)? Or else, Michael might also complain that the proposed definition/analysis is circular and amounts to saying that what makes red apples red is that they look red. Although, to be sure, our "in normal conditions" clause does some important work. I did borrow some ideas from Gareth Evans and David Wiggins to deal with this issue but I'd like to hear your thoughts first. — Pierre-Normand

I think you're overcomplicating it, being "bewitched by language" as Wittgenstein would put it.

An apple reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm. When our eyes respond to light with a wavelength of 700nm we see a particular colour. We name this colour "red". We then describe an object that reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm as "being red".

The indirect realist recognises that the colour I see in response to my eyes responding to a particular wavelength of light (and the colour I see when I dream and hallucinate) is distinct from an object's surface layer of atoms and its disposition to reflect a particular wavelength of light. The indirect realist recognises that this colour I see is a mental phenomenon and that this colour is the intermediary through which I am made indirectly aware of an object with a surface layer of atoms with a disposition to reflect light with a wavelength of 700nm (assuming that this is a "veridical" experience and not a dream or hallucination).

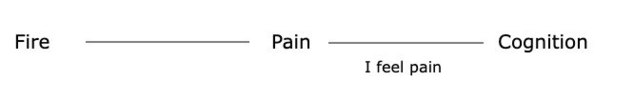

Perhaps this is clearer if we consider something like "the fire is painful" rather than "the apple is red". -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThis is evidenced by the fact that we can make sense of different people seeing a different coloured dress when looking at this photo: — Michael

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThis is evidenced by the fact that we can make sense of different people seeing a different coloured dress when looking at this photo: — Michael

Yes, we can make sense of this. I think the fact that some people's visual systems cause them to stubbornly see it as gold and white while other people stubbornly see it as black and blue indeed reveals intrinsic differences about the way their visual systems are calibrated in the context of interpreting some ambiguous photographs. Other people also are able to experience a periodic gestalt switch between the two interpretations. (I myself always see this dress as gold and white and have a hard time operating the gestalt switch).

There is another thing to notice about this interesting phenomenon that should give you pause. When seeing such a dress in real life conditions, where cues about the spectral compositions of the ambient light are abundant, no such disagreement about the two colors of the dress occur. Furthermore, people who disagree about the interpretations of the picture can communicate their disagreement by pointing at external color swatches (paint samples) that are unambiguously blue, black, gold and white to communicate how it is that the pictured dress appears to be colored to them. Here again, their reliable agreement on the color of the reference samples ought to give you pause. -

Michael

16.9kFurthermore, people who disagree about the interpretations of the picture can communicate their disagreement by pointing at external paint color samples that are unambiguously blue, black, gold and white to communicate how it is that the pictured dress appears to be colored to them. Here again, their agreement on the color of the samples ought to give you pause. — Pierre-Normand

Michael

16.9kFurthermore, people who disagree about the interpretations of the picture can communicate their disagreement by pointing at external paint color samples that are unambiguously blue, black, gold and white to communicate how it is that the pictured dress appears to be colored to them. Here again, their agreement on the color of the samples ought to give you pause. — Pierre-Normand

It doesn't give me pause. Given that our eyes and brains are mostly similar, and given causal determinism, it stands to reason that the same kind of stimulus will mostly cause the same kind of effect.

But it is still the case that the cause is not the effect and that colour terms like "red" and "blue" can be used to refer to both the cause and the effect, and so you need to take care not to conflate the two, but it seems that direct realists do conflate. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kIt would be interesting to hear what a human with his eyes replaced with those of a mantis shrimp (with their 12 channel colour vision compared to our 3) would say. — Michael

Pierre-Normand

2.9kIt would be interesting to hear what a human with his eyes replaced with those of a mantis shrimp (with their 12 channel colour vision compared to our 3) would say. — Michael

The worst case scenario is that they would become blind. The best case scenario is that they would experience no change at all in the way they see colors since the dodecachromatic color space that the new eyes can discriminate would still map on the trichromatic structure of the primary visual areas in the human cerebral cortex. After a very long unconscious process of rewiring of the whole brain, helped with the development of new color concepts, their vision might change in such a way that they could actually discriminate and conceptualise new color discriminations and relationships. They'd still ascribe the colors within this richer color space to the external objects that they see.

Claude 3's elaborationClaude 3:

The worst case scenario you mention - that the person would become blind - is a realistic possibility, given the radical mismatch between the mantis shrimp's visual system and the human brain. Even if the physical connection could be made, there's no guarantee that the brain would be able to make sense of the radically different input.

The best case scenario - that the person's color experience would remain unchanged - is also plausible, for the reason you give. The dodecachromatic information from the mantis shrimp eyes might simply be mapped onto the existing trichromatic processing structures in the human brain, resulting in no subjective change in color perception. This highlights the important point that color experience depends not just on the raw sensory input, but on how that input is processed and interpreted by the brain.

The intermediate scenario you suggest - that over time, the brain might rewire itself to take advantage of the richer color information, leading to new color discriminations and concepts - is intriguing. It suggests a way in which our color perception might be expanded or enriched, not just by changing our sensory organs, but by developing new neural processing structures and conceptual resources to handle more fine-grained color information.

Importantly, as you note, even in this scenario, the person would still ascribe the newly differentiated colors to external objects. The enriched color perception would still be understood as tracking objective features of the world (presumably finer-grained differences in surface spectral reflectance profiles), not merely as a subjective artifact of the novel visual system.

This connects back nicely to the ideas we were discussing about Evans' account of natural kind concepts and epistemological disjunctivism. Even as our discriminatory capacities change and develop, they can still put us in direct contact with objective features of the world, as long as they are operating under the conditions for which they were developed and are reliably tracking the relevant environmental properties.

The mantis shrimp example is a nice way of illustrating the flexibility and potential for expansion in our color concepts, while still maintaining a realist commitment to colors as objective properties of objects. It suggests that our current trichromatic color space is not necessarily the final word on color perception, but rather reflects the particular discriminatory capacities that have been shaped by our evolutionary history and practical engagements with our environment.

At the same time, the example also highlights the deep interconnection between our sensory capacities, neural processing structures, and conceptual resources in shaping our perceptual experience. It's not just a matter of swapping out one sensory module for another, but of the complex interplay between sensation, perception, and cognition. -

Michael

16.9kThe mantis shrimp example is a nice way of illustrating the flexibility and potential for expansion in our color concepts, while still maintaining a realist commitment to colors as objective properties of objects. — Pierre-Normand

Michael

16.9kThe mantis shrimp example is a nice way of illustrating the flexibility and potential for expansion in our color concepts, while still maintaining a realist commitment to colors as objective properties of objects. — Pierre-Normand

This is equivocation. There is "colour" as an object's surface disposition to reflect a certain wavelength of light and there is "colour" as the mental phenomenon that differs between those with 3 channel colour vision and those with 12 channel colour vision (and that occurs when we dream and hallucinate).

Despite sharing the same label these are distinct things – albeit causally covariant given causal determinism.

Those with 3 channel colour vision and those with 12 channel colour vision will agree that some object reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm, but they will see it to have a different colour appearance.

They'd still ascribe the colors within this richer color space to the external objects that they see. — Pierre-Normand

If they're direct realists, and they'd be mistaken. Naive colour realism is disproven by our scientific understanding of perception and the world. -

flannel jesus

2.9kThis is equivocation. There is "colour" as an object's surface disposition to reflect a certain wavelength of light and there is "colour" as the mental phenomenon — Michael

flannel jesus

2.9kThis is equivocation. There is "colour" as an object's surface disposition to reflect a certain wavelength of light and there is "colour" as the mental phenomenon — Michael

Yeah, this confusion seems common. -

fdrake

7.2kThose with 3 channel colour vision and those with 12 channel colour vision will agree that some object reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm, but they will see it to have a different colour appearance. — Michael

fdrake

7.2kThose with 3 channel colour vision and those with 12 channel colour vision will agree that some object reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm, but they will see it to have a different colour appearance. — Michael

You could end up with a statement like:

(Shrimp) Mantis Shrimp Human sees X as P(X) and calls it "P(X)" if and only if human sees X as Q(X) and calls it "Q(X)".

Predicating of the distal object X now makes sense because we've reintroduced the idea that properties of distal objects influence the kinds they are seen and labelled as.

Do you think you need a numerical identity between the state of being that Mantis Shrimp Human has when they count X as P(X) and the human's that counts X as Q(X) even when P and Q have the same extension?

I don't particularly like my own formulation of (Shrimp) btw, as it bifurcates seeing as a perceptual act and classification as a linguistic one, whereas there's evidence that the two are reciprocally related - both predictively/inferentially/causally and phenomenologically (citation needed). -

Michael

16.9kI don't particularly like my own formulation of (Shrimp) btw, as it bifurcates seeing as a perceptual act and classification as a linguistic one, whereas there's evidence that the two are reciprocally related - both predictively/inferentially/causally and phenomenologically (citation needed). — fdrake

Michael

16.9kI don't particularly like my own formulation of (Shrimp) btw, as it bifurcates seeing as a perceptual act and classification as a linguistic one, whereas there's evidence that the two are reciprocally related - both predictively/inferentially/causally and phenomenologically (citation needed). — fdrake

Are you suggesting that deaf and illiterate mutes don't see colours (or see everything to be the same colour)?

You could end up with a statement like:

(Shrimp) Mantis Shrimp Human sees X as P(X) and calls it "P(X)" if and only if human sees X as Q(X) and calls it "Q(X)".

Predicating of the distal object X now makes sense because we've reintroduced the idea that properties of distal objects influence the kinds they are seen and labelled as.

Do you think you need a numerical identity between the state of being that Mantis Shrimp Human has when they count X as P(X) and the human's that counts X as Q(X) even when P and Q have the same extension? — fdrake

I'm not entirely sure what you're trying to ask here.

My argument is that:

1. There is some stimulus X

2. There is some organism A and some different organism B

3. Given their different physiologies, organisms A and B have different experiences when stimulated by stimulus X

4. Some of the words that organisms A and B use to presumptively describe X in fact describe some aspect of their individual experience (and that is not an aspect of the other organism's experience).

5. Colour words are one such example. -

Luke

2.7kThe meaning of "direct perception" is such that if perception is direct then perception provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects. Therefore, if perception does not provide us with direct knowledge of distal objects then perception is not direct.

Luke

2.7kThe meaning of "direct perception" is such that if perception is direct then perception provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects. Therefore, if perception does not provide us with direct knowledge of distal objects then perception is not direct.

Given our scientific understanding of the world and perception it is clear that perception does not provide us with direct knowledge of distal objects. Therefore, perception is not direct. — Michael

Which scientific understanding of the world and perception are you referring to? I might agree that perception does not always provide us with direct knowledge of distal objects, such as in cases of illusion, hallucination or error. But I do not agree that perception never provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects. In fact, I would say that perception more often than not does provide us with direct knowledge of distal objects.

Otherwise, I take it you are referring to the world as it is in itself. Yet, you stated in a recent post that:

that they have a "real look" is a confusion, much like any claim that distal objects have a "real feel" would be a confusion. There just is how things look to me and how things feel to you given our individual physiology. — Michael

That is, you appear to reject the possibility of perceiving the world as it is in itself. -

Michael

16.9k

Michael

16.9k

For example, we see colours. As per the Standard Model, colours are not a property of distal objects. Distal objects are just a collection of wave-particles. Colours are a mental phenomenon often caused by the body responding to particular wavelengths of light. I have direct knowledge of the colour red and indirect knowledge of a distal object reflecting light with a wavelength of 700nm. -

Michael

16.9kI don't follow. In what sense is your knowledge indirect here? Is the wavelength of the light a property of the distal object? — Luke

Michael

16.9kI don't follow. In what sense is your knowledge indirect here? Is the wavelength of the light a property of the distal object? — Luke

I know that I see the colour red.

I know that in most humans seeing the colour red usually occurs when the eyes react to light with a wavelength of 700nm.

I infer from this that I am looking at an object that reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm.

Of course this is only true because I am somewhat educated in science. For many, e.g. young children, all they know is that they see the colour red. They don't know anything about electromagnetism and so don't know anything about the distal object's mind-independent properties. -

Luke

2.7k

Luke

2.7k

Again:

I might agree that perception does not always provide us with direct knowledge of distal objects, such as in cases of illusion, hallucination or error. But I do not agree that perception never provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects. In fact, I would say that perception more often than not does provide us with [some] direct knowledge of distal objects. — Luke

I take it that the position of indirect realism is that perception never provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects. And the position of naive realism is that perception always provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects? -

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Harry Hindu

5.9k

I think that the indirect/direct distinction is a false dichotomy.

If we know that the wavelength is 700nm and that the apple is reflecting this wavelength of light while absorbing others, then what is different in the knowledge that an indirect realist has vs a direct one?An apple reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm. When our eyes respond to light with a wavelength of 700nm we see a particular colour. We name this colour "red". We then describe an object that reflects light with a wavelength of 700nm as "being red". — Michael

What is useful in knowing that the wavelength if light being reflected in our eyes is 700nm? What is useful in knowing that the apple is red? What is useful is knowing that the apple is either ripe or rotten and the color of the apple informs us which is the case. If knowing the apple is ripe because it is red is knowing something about the apple instead of the light, what is different between what the direct realist knows vs the indirect one?

What is the difference between direct knowledge and indirect knowledge of something if you both end up knowing the same thing?

The indirect realist recognises that this colour I see is a mental phenomenon and that this colour is the intermediary through which I am made indirectly aware of an object with a surface layer of atoms with a disposition to reflect light with a wavelength of 700nm (assuming that this is a "veridical" experience and not a dream or hallucination). — Michael

What is the "I" that is made indirectly aware via mental phenomenon? How is it separate from the colours, mental phenomenon and other objects to say that the mental phenomenon is an "intermediary through which I am made indirectly aware..." -

Michael

16.9kI take it that the position of indirect realism is that perception never provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects. And the position of naive realism is that perception always provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects? — Luke

Michael

16.9kI take it that the position of indirect realism is that perception never provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects. And the position of naive realism is that perception always provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects? — Luke

Take the picture here. If indirect realism is true then if we remove the mental image then we have no knowledge of the distal object (or, to be more precise, any knowledge of the distal object has been gained by some means other than perception). And I believe that's correct. The mental image is the necessary intermediary. -

Michael

16.9kWhat is useful is knowing that the apple is either ripe or rotten and the color of the apple informs us which is the case. — Harry Hindu

Michael

16.9kWhat is useful is knowing that the apple is either ripe or rotten and the color of the apple informs us which is the case. — Harry Hindu

Okay. We have direct knowledge of colours, which are a mental phenomenon. Given that we have inferential – i.e. indirect – knowledge of the apple's ripeness, which is a mind-independent property.

Our perception of the apple's mind-independent property is indirect.

What is the "I" that is made indirectly aware via mental phenomenon? How is it separate from the colours, mental phenomenon and other objects to say that the mental phenomenon is an "intermediary through which I am made indirectly aware..." — Harry Hindu

They're different aspects of consciousness, resulting from different areas of brain activity. The blind man has a self but doesn't experience visual phenomena because his visual cortex doesn't function. -

Luke

2.7kTake the picture here. If indirect realism is true then if we remove the mental image then we have no knowledge of the distal object. And I believe that's correct. The mental image is the necessary intermediary. — Michael

Luke

2.7kTake the picture here. If indirect realism is true then if we remove the mental image then we have no knowledge of the distal object. And I believe that's correct. The mental image is the necessary intermediary. — Michael

The picture maintains what I consider to be the false assumption of indirect realism: that we require a second-order cognition/awareness/perception in order to perceive the first-order perceptions. In other words, cognition/awareness/perception of perceptions, which seems to imply an infinite regress. Perceptions (i.e. first-order perceptions) are here treated as not something already present to consciousness, or as if they were themselves external objects. -

Michael

16.9kThe picture maintains what I consider to be the false assumption of indirect realism: that we require a second-order cognition/awareness/perception in order to perceive the first-order perceptions. In other words, cognition/awareness/perception of perceptions, which seems to imply an infinite regress. Perceptions (i.e. first-order perceptions) are here treated as not something already present to consciousness, or as if they were themselves external objects. — Luke

Michael

16.9kThe picture maintains what I consider to be the false assumption of indirect realism: that we require a second-order cognition/awareness/perception in order to perceive the first-order perceptions. In other words, cognition/awareness/perception of perceptions, which seems to imply an infinite regress. Perceptions (i.e. first-order perceptions) are here treated as not something already present to consciousness, or as if they were themselves external objects. — Luke

Do I see colours when I dream? Does the schizophrenic hear voices when hallucinating? I say "yes" to both.

This is where you're getting confused by grammar into thinking that indirect realists are saying something they're not. -

Luke

2.7kDo I see things when I dream? Does the schizophrenic hear voices when suffering a psychotic episode? — Michael

Luke

2.7kDo I see things when I dream? Does the schizophrenic hear voices when suffering a psychotic episode? — Michael

Dreams are not perceptions, and "hearing voices" is an abnormal case of perception.

This is where you're getting confused by grammar into thinking that indirect realists are saying something they're not. — Michael

Your picture suggests otherwise. -

Michael

16.9kDreams are not perceptions, and "hearing voices" is an abnormal case of perception. — Luke

Michael

16.9kDreams are not perceptions, and "hearing voices" is an abnormal case of perception. — Luke

It is nonetheless the case that I see and hear things when I dream and hallucinate and that the things I see and hear when I dream and hallucinate are mental phenomena. The Common Kind Claim says that waking veridical experiences are of the same kind as dreams and hallucinations (e.g. the activity of the sensory cortexes) – differing only in their cause – and so that the things I see (e.g. colours) and hear when having a waking veridical experience are also mental phenomena.

Your picture suggests otherwise. — Luke

Perhaps this will make it clearer:

The same principle holds for smelling and tasting and hearing and seeing. -

Michael

16.9kIf I stub my toe, injure my toe, and feel the pain in my toe, is it your position that I am feeling it in my prefrontal cortex? — NOS4A2

Michael

16.9kIf I stub my toe, injure my toe, and feel the pain in my toe, is it your position that I am feeling it in my prefrontal cortex? — NOS4A2

I think that there are pain receptors in the toe, that these send signals to the brain, and then there is pain when the relevant areas in the brain are active. The brain is clever and able to make it seem as if the pain is literally in the foot, but that cleverness also leaves us susceptible to phantom limb syndrome.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum