-

flannel jesus

2.9k

flannel jesus

2.9k

What are hallucinations if not an experience of a distal object without a distal object?also believe that distal objects are constituents of experience in the sense that you could not have an experience of a distal object without them. — Luke -

Luke

2.7kWhat are hallucinations if not an experience of a distal object without a distal object? — flannel jesus

Luke

2.7kWhat are hallucinations if not an experience of a distal object without a distal object? — flannel jesus

Yes, but not all experiences of distal objects are hallucinations. Perhaps I should have said "you could not have a non-hallucinatory experience of a distal object without them". -

Michael

16.9kI also believe that distal objects are constituents of experience in the sense that you could not have an experience of a distal object without them. — Luke

Michael

16.9kI also believe that distal objects are constituents of experience in the sense that you could not have an experience of a distal object without them. — Luke

That's not the sense that is meant by the naive realist and rejected by the indirect realist. The sense that is meant by the naive realist and rejected by the indirect realist is the sense that would entail naive realism.

Why wouldn't you use the same argument against naive realists? — Luke

Because this is what naive realism claims:

"Distal objects are constituents of experience such that experience provides us with direct knowledge of distal objects, and so there is no epistemological problem of perception."

This claim has nothing to do with the grammar of "I see X".

Your insistence of continually addressing the grammar of "I see X" is the very conceptual confusion that I am trying to avoid. It's a red herring. -

Michael

16.9kThese are the three positions:

Michael

16.9kThese are the three positions:

1. Naive realism: a) naive realism is true and b) I experience distal objects

2. Indirect realism: a) naive realism is false and b) I experience mental phenomena

3. Non-naive direct realism: a) naive realism is false and b) I experience distal objects

Each a) is the relevant philosophical issue that concerns the epistemological problem of perception.

Each b) is an irrelevant semantic issue. They are not mutually exclusive given that "I experience X" doesn't just mean one thing.

Naive realism is false and I experience both distal objects (e.g. apples) and mental phenomena (e.g. colours and pain).

Therefore indirect realism and non-naive direct realism are both true and amount to the same philosophical position; the rejection of naive realism. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kI like the examples you (and Claude) have been giving, but I don't seem to draw the same conclusion.

Pierre-Normand

2.9kI like the examples you (and Claude) have been giving, but I don't seem to draw the same conclusion.

I don't think indirect realism presupposes or requires that phenomenal experience is somehow a passive reflection of sensory inputs. Rather the opposite, a passive brain reflecting its environment seems to be a direct realist conception. These examples seem to emphasize the active role the brain plays in constructing the sensory panoply we experience, which is perfectly in line with indirect realism.

For instance, in the very striking cube illusion you presented, we only experience the square faces as brown and orange because the brain is constructing an experience that reflects its prediction about the physical state of the cube: that the faces must in fact have different surface properties, in spite of the same wavelengths hitting the retina at the two corresponding retinal regions. — hypericin

The neural processing performed by the brain on raw sensory inputs like retinal images plays an important causal role in enabling human perception of invariant features in the objects we observe. However, our resulting phenomenology - how things appear to us - consists of more than just this unprocessed "sensory" data. The raw nerve signals, retinal images, and patterns of neural activation across sensory cortices are not directly accessible to our awareness.

Rather, what we are immediately conscious of is the already "processed" phenomenological content. So an indirect realist account should identify this phenomenological content as the alleged "sense data" that mediates our access to the world, not the antecedent neural processing itself. @Luke also aptly pointed this out. Saying that we (directly) perceive the world as flat and then (indirectly) infer its 3D layout misrepresents the actual phenomenology of spatial perception. This was the first part of my argument against indirect realism.

The second part of my argument is that the sort of competence that we acquire to perceive those invariants aren't competences that our brains have (although our brains enable us to acquire them) but rather competences that are inextricably linked to our abilities to move around and manipulate objects in the world. Learning to perceive and learning to act are inseparable activities since they normally are realized jointly rather like a mathematician learns the meanings of mathematical theorems by learning how to prove them or make mathematical demonstrations on the basis of them.

In the act of reaching out for an apple, grasping it and bringing it closer to your face, the success of this action is the vindication of the truth of the perception. Worries about the resemblance between the seen/manipulated/eaten apple and the world as it is in itself arise on the backdrop of dualistic philosophies rather than being the implications of neuroscientific results.

The starting point of taking phenomenal experience itself as the problematic "veil" separating us from direct access to reality is misguided. The phenomenological content is already an achievement of our skilled engagement with the world as embodied agents, not a mere representation constructed by the brain. -

flannel jesus

2.9kthat extra stipulation makes it a tautology, since a non hallucinatory experience of a distal object by definition requires the existence of a distal object.

flannel jesus

2.9kthat extra stipulation makes it a tautology, since a non hallucinatory experience of a distal object by definition requires the existence of a distal object.

So I have to agree with you, because I agree that tautologies are valid -

Michael

16.9kRather, what we are immediately conscious of is the already "processed" phenomenological content. So an indirect realist account should identify this phenomenological content as the alleged "sense data" that mediates our access to the world, not the antecedent neural processing itself. — Pierre-Normand

Michael

16.9kRather, what we are immediately conscious of is the already "processed" phenomenological content. So an indirect realist account should identify this phenomenological content as the alleged "sense data" that mediates our access to the world, not the antecedent neural processing itself. — Pierre-Normand

If someone claims that the direct object of perceptual knowledge is the already-processed phenomenological content, and that through this we have indirect knowledge of the external stimulus or distal cause, would you call them a direct realist or an indirect realist?

I'd call them an indirect realist. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThe neural processing performed by the brain on raw sensory inputs like retinal images plays an important causal role in enabling human perception of invariant features in the objects we observe. However, our resulting phenomenology - how things appear to us - consists of more than just this unprocessed "sensory" data. The raw nerve signals, retinal images, and patterns of neural activation across sensory cortices are not directly accessible to our awareness.

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThe neural processing performed by the brain on raw sensory inputs like retinal images plays an important causal role in enabling human perception of invariant features in the objects we observe. However, our resulting phenomenology - how things appear to us - consists of more than just this unprocessed "sensory" data. The raw nerve signals, retinal images, and patterns of neural activation across sensory cortices are not directly accessible to our awareness.

Rather, what we are immediately conscious of is the already "processed" phenomenological content. So an indirect realist account should identify this phenomenological content as the alleged "sense data" that mediates our access to the world, not the antecedent neural processing itself. Luke also aptly pointed this out. Saying that we (directly) perceive the world as flat and then (indirectly) infer its 3D layout misrepresents the actual phenomenology of spatial perception. This was the first part of my argument against indirect realism.

The second part of my argument is that the sort of competence that we acquire to perceive those invariants aren't competences that our brains have (although our brains enable us to acquire them) but rather competences that are inextricably linked to our abilities to move around and manipulate objects in the world. Learning to perceive and learning to act are inseparable activities since they normally are realized jointly rather like a mathematician learns the meanings of mathematical theorems by learning how to prove them or make mathematical demonstrations on the basis of them.

In the act of reaching out for an apple, grasping it and bringing it closer to your face, the success of this action is the vindication of the truth of the perception. Worries about the resemblance between the seen/manipulated/eaten apple and the world as it is in itself arise on the backdrop of dualistic philosophies rather than being the implications of neuroscientific results.

The indirect realist's starting point of taking phenomenal experience itself as the problematic "veil" separating us from direct access to reality is misguided. The phenomenological content is already an achievement of our skilled engagement with the world as embodied agents, not a mere representation constructed by the brain. — Pierre-Normand -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kIf someone claims that the direct object of perceptual knowledge is the already-processed phenomenological content, and that through this we have indirect knowledge of the external stimulus or distal cause, would you call them a direct realist or an indirect realist?

Pierre-Normand

2.9kIf someone claims that the direct object of perceptual knowledge is the already-processed phenomenological content, and that through this we have indirect knowledge of the external stimulus or distal cause, would you call them a direct realist or an indirect realist?

I'd call them an indirect realist. — Michael

I am saying that if you are an indirect realist, then what stands between you and the distal cause of your perceptions should be identified with the already-processed phenomenological content. This is because, on the indirect realist view, your immediate perceptions cannot be the invisible raw sensory inputs or neural processing itself. Rather, what you are directly aware of is the consciously accessible phenomenology resulting from that processing.

In contrast, a direct realist posits no such intermediate representations at all. For the direct realist, the act of representing the world is a capacity that the human subject exercises in directly perceiving distal objects. On this view, phenomenology is concerned with describing and analyzing the appearances of those objects themselves, not the appearances of some internal "representations" of them (which would make them, strangely enough, appearances of appearances). -

Michael

16.9kOn this view, phenomenology is concerned with describing and analyzing the appearances of those objects themselves, not the appearances of some internal "representations" of them (which would make them, strangely enough, appearances of appearances). — Pierre-Normand

Michael

16.9kOn this view, phenomenology is concerned with describing and analyzing the appearances of those objects themselves, not the appearances of some internal "representations" of them (which would make them, strangely enough, appearances of appearances). — Pierre-Normand

The indirect realist doesn’t claim that there are “appearances of appearances”.

The indirect realist claims that a distal object's appearance is the intermediate representation.

We have direct knowledge of a distal object's appearance and through that indirect knowledge of a distal object.

You're describing indirect realism but calling it direct realism for some reason.

The direct realist rejects any distinction between a distal object's appearance and the distal object itself, entailing such things as the naive realist theory of colour. -

frank

19kI think the idea that one must start with "atomic" concepts isn't wholly inconsistent with the sort of holism Wittgenstein advocated — Pierre-Normand

frank

19kI think the idea that one must start with "atomic" concepts isn't wholly inconsistent with the sort of holism Wittgenstein advocated — Pierre-Normand

Atomism is indispensable. As long as the advocate of embodied consciousness understands that, all is well. It's just a shift in perspective of the sort that already exists in biology, so really, it just comes down to a matter of emphasis. -

fdrake

7.2k

fdrake

7.2k

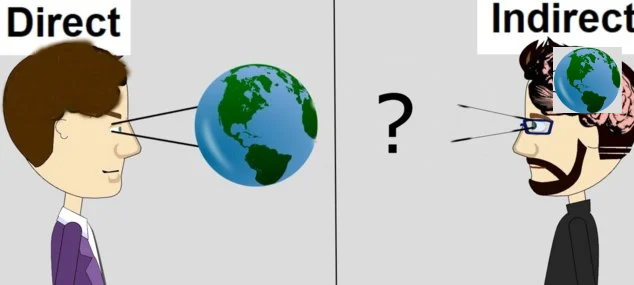

How do you conceptualise a distal object in the second construal of indirect realism? It looks to me like there's an intermediary perceptual object in a representation relationship with distal objects in only the upper indirect realist's portrayal. In the lower indirect realist's account there doesn't seem to be a distal object of a perceptual act, and thus no relation with one, and thus no representation relationship with one. -

Michael

16.9kHow do you conceptualise a distal object in the second construal of indirect realism? — fdrake

Michael

16.9kHow do you conceptualise a distal object in the second construal of indirect realism? — fdrake

Depends on the indirect realist.

Some may believe that distal objects resemble our mental image, and so would replace the question mark with the Earth as shown in the person’s head.

Some may believe that distal objects resemble our mental image only with respect to so-called "primary" qualities, and so would replace the question mark with an uncoloured version of the Earth as shown in the person’s head.

Some may believe that distal objects do not resemble our mental image at all. A scientific realist would replace the question mark with the wave-particles of the Standard Model. A Kantian wouldn’t replace the question mark at all, simply using it to signify unknowable noumena.

What defines them as being indirect realists is in believing that we have direct knowledge only of a mental image. Direct realists believe that we have direct knowledge of the distal object because nothing like a mental image exists (the bottom drawing of direct realism). -

fdrake

7.2kWhat defines them as being indirect realists is in believing that we have direct knowledge only of a mental representation. Direct realists believe that we have direct knowledge of the distal object because nothing like a mental representation exists (the bottom drawing of direct realism). — Michael

fdrake

7.2kWhat defines them as being indirect realists is in believing that we have direct knowledge only of a mental representation. Direct realists believe that we have direct knowledge of the distal object because nothing like a mental representation exists (the bottom drawing of direct realism). — Michael

Another possibility was outlined by Pierre-Normand below.

In contrast, a direct realist posits no such intermediate representations at all. For the direct realist, the act of representing the world is a capacity that the human subject exercises in directly perceiving distal objects. On this view, phenomenology is concerned with describing and analyzing the appearances of those objects themselves, not the appearances of some internal "representations" of them (which would make them, strangely enough, appearances of appearances). — Pierre-Normand

The distinction between "no such intermediate representation" and "nothing like a mental representation exists". The other realist alternative is that the perceptual relationship itself is a representation relationship. IE, there is no intermediate representation between distal object (or cause) of a perceptual object. But that would not be because there is no representation - or an appearance even - , but because there is no intermediate object or relation between the distal object/cause and the perceiver.

In terms of the diagram, you'd label the lines in the bottom left "representation".

For illustrative purposes anyway, an enactivist would hate the diagrams focussing on vision, or labelling those arrows as representation relationships in the first place! -

Michael

16.9k

Michael

16.9k

I don’t see how his account differs from indirect realism. Indirect realists simply claim that the thing we have direct knowledge of in perception is some sort of mental phenomenon, not some distal object, and so our knowledge of distal objects is indirect, entailing the epistemological problem of perception.

We can argue over what sort of mental phenomenon is the direct source of knowledge - sense data or qualia or representation or appearance or processed phenomenological content or other - but it all amounts to indirect realism in the end. -

frank

19k

frank

19k

But a person can experience the world without engaging it in any way. If you mean the character of experience is shaped by interaction, I would agree to some extent. Some of it is just innate, though. -

creativesoul

12.2kWhat are hallucinations if not an experience of a distal object without a distal object? — flannel jesus

Malfunctioning biological machinery. -

hypericin

2.1k

hypericin

2.1k

Then, your first part was an argument against a straw man, since an indirect realist can (and should, and does, imo) agree that phenomenological content is only accessible following all neural processing.This was the first part of my argument against indirect realism. — Pierre-Normand -

hypericin

2.1kAs the MIT roboticist Rodney Brooks once argued, the terrain itself is its own best model - it doesn't need to be re-represented internally — Pierre-Normand

hypericin

2.1kAs the MIT roboticist Rodney Brooks once argued, the terrain itself is its own best model - it doesn't need to be re-represented internally — Pierre-Normand

I thought this was curious, so I looked it up. It is mentioned in this article:

https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/08/21/133411/rodney-brooks/

“The world is its own best model,” Brooks wrote. “It is always exactly up to date. It always contains every detail there is to be known. The trick is to sense it appropriately and often enough.”

The inspiration:

“I’m watching these insects buzz around. And they’ve got tiny, tiny little brains, some as small 100,000 neurons, and I’m thinking, ‘They can’t do the mathematics I’m asking my robots to do for an even simpler thing. They’re hunting. They’re eating. They’re foraging. They’re mating. They’re getting out of my way when I’m trying to slap them. How are they doing all this stuff? They must be organized differently.’

This is the inventor of the Roomba, which to me tells you everything you need to know. Which is not to put him down the slightest bit. He had the insight everyone else missed: Everyone trying to build robots implicitly had the idea of modelling higher animals. But why do this? This is not the path evolution took. Why not instead draw inspiration from vastly simpler creatures, who do not model at all?

This is what I proposed as the meaning of "direct perception", to contrast with indirect perception:

Think of an amoeba, light hits a photo receptor, and by some logic the amoeba moves one way or the other.If you regard this as "perception", then this is direct perception — hypericin

Human brains, on the other hand, fine tuned by millions of years of evolution and equipped with unmatched computational power, are modelers par excellence. We are not organized like insects, who respond directly to the environment. We build models, and then respond to the models. And phenomenal experience is exactly those models. It is nothing less than a virtual world, and the basis for all of our decisions and actions.

In their manner of responding intelligently to their environment human brains powerfully leverage the same principle of indirection we see everywhere in engineering.

This is known as Fundamental theorem of software engineering:

All problems in computer science can be solved by another level of indirection -

hypericin

2.1kI would say that illusions and hallucinations are phenomenal experiences, instead of saying that they are the consequences of phenomenal experiences — Luke

hypericin

2.1kI would say that illusions and hallucinations are phenomenal experiences, instead of saying that they are the consequences of phenomenal experiences — Luke

I'm not saying that they are the consequences of phenomenal experience. I'm saying that mediation makes illusions and hallucinations possible, mediation is the condition for the existence of perceptual errors. This is most clear to me with hallucination: without the meditating layer of phenomenal experience, we simply couldn't hallucinate. -

hypericin

2.1kThe second part of my argument is that the sort of competence that we acquire to perceive those invariants aren't competences that our brains have (although our brains enable us to acquire them) — Pierre-Normand

hypericin

2.1kThe second part of my argument is that the sort of competence that we acquire to perceive those invariants aren't competences that our brains have (although our brains enable us to acquire them) — Pierre-Normand

I find this notion very problematic. When we learn anything, we are training our brains to acquire new competences. Not any other organ. Even though, to learn necessarily involves interaction with the environment.

When we learn to play the piano it is not our fingers that are becoming more clever, but our brains. When we learn to see, our brain, not our eyes, gains the competence to process sensory inputs in such a way that the phenomenological experience of the world we are familiar with is possible. Damage to the occipital lobe of the brain, not to other parts of the body, renders us blindsighted. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThen, your first part was an argument against a straw man, since an indirect realist can (and should, and does, imo) agree that phenomenological content is only accessible following all neural processing. — hypericin

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThen, your first part was an argument against a straw man, since an indirect realist can (and should, and does, imo) agree that phenomenological content is only accessible following all neural processing. — hypericin

Remember that you responded to an argument that I (and Claude 3) had crafted in response to @Michael. He may have refined his position since we began this discussion but he had long taken the stance that what I was focussing on as the content of perceptual experience wasn't how things really look but rather was inferred from raw appearances that, according to him, corresponded more closely to the stimulation of the sense organs. Hence, when I was talking about a party balloon (or house) appearing to get closer, and not bigger, as we walk towards it, he was insisting that the "appearance" (conceived as the sustained solid angle in the visual field) of the object grows bigger. This may be true only when we shift our attention away from the perceived object to, say, how big a portion of the background scenery is being occluded by it (which may indeed be a useful thing to do when we intend to produce a perspectival drawing.) -

Michael

16.9kHe may have refined his position since we began this discussion but he had long taken the stance that what I was focussing on as the content of perceptual experience wasn't how things really look but rather was inferred from raw appearances that, according to him, corresponded more closely to the stimulation of the sense organs. — Pierre-Normand

Michael

16.9kHe may have refined his position since we began this discussion but he had long taken the stance that what I was focussing on as the content of perceptual experience wasn't how things really look but rather was inferred from raw appearances that, according to him, corresponded more closely to the stimulation of the sense organs. — Pierre-Normand

I am saying that appearances are mental phenomena, often caused by the stimulation of some sense organ (dreams and hallucinations are the notable exceptions), and that given causal determinism, the stimulation of a different kind of sense organ will cause a different kind of mental phenomenon/appearance.

The naïve view that projects these appearances onto some distal object (e.g. the naïve realist theory of colour), such that they have a "real look" is a confusion, much like any claim that distal objects have a "real feel" would be a confusion. There just is how things look to me and how things feel to you given our individual physiology.

It seems that many accept this at least in the case of smell and taste but treat sight as special, perhaps because visual phenomena are more complex than other mental phenomena and because depth is a quality in visual phenomena, creating the illusion of conscious experience extending beyond the body. But there's no reason to believe that photoreception is special, hence why I question the distinction between so-called "primary" qualities like visual geometry and so-called "secondary" qualities like smells and tastes (and colours).

Although even if I were to grant that some aspect of mental phenomena resembles some aspect of distal objects, it is nonetheless the case that it is only mental phenomena of which we have direct knowledge in perception, with any knowledge of distal objects being inferential, i.e. indirect, entailing the epistemological problem of perception and the viability of scepticism. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kI am saying that appearances are mental phenomena, often caused by the stimulation of some sense organ (dreams and hallucinations are the notable exceptions), and that given causal determinism, the stimulation of a different kind of sense organ will cause a different kind of mental phenomenon/appearance. — Michael

Pierre-Normand

2.9kI am saying that appearances are mental phenomena, often caused by the stimulation of some sense organ (dreams and hallucinations are the notable exceptions), and that given causal determinism, the stimulation of a different kind of sense organ will cause a different kind of mental phenomenon/appearance. — Michael

I am going to respond to this separately here, and respond to your comments about projecting appearances on distal objects (and the naïve theory of colours) in a separate post.

I agree that appearances are mental phenomena, but a direct realist can conceive of those phenomena as actualisations of abilities to perceive features of the world rather than as proximal representations that stand in between the observer and the world (or as causal intermediaries.)

Consider a soccer player who scores a goal. Their brain and body play an essential causal role in this activity but the act of scoring the goal, which is the actualization of an agentive capacity that the soccer player has, doesn't take place within the boundaries of their body, let alone within their brain. Rather, this action takes place on the soccer field. The terrain, the soccer ball and the goal posts all play a role in the actualisation of this ability.

Furthemore, the action isn't caused by an instantaneous neural output originating from the motor cortex of the player but is rather a protracted event that may involve outplaying a player from the opposite team (as well as the goalie) and acquiring a direct line of shot.

Lastly, this protracted episode that constitutes the action of scoring a soccer goal includes as constituent parts of it several perceptual acts. Reciprocally, most of those perceptual acts aren't standalone and instantaneous episodes consisting in the player acquiring photograph-like pictures of the soccer field, but rather involve movements and actions that enables them to better grasp (and create) affordances for outplaying the other players and to accurately estimate the location of the goal in egocentric space.

A salient feature of the phenomenology of the player is that, at some point, an affordance for scoring a goal has been honed into and the decisive kick can be delivered. But what makes this perceptual content what it is isn't just any intrinsic feature of the layout of the visual field at that moment but rather what it represents within the structured and protracted episode that culminated in this moment. The complex system that "computationally" generated the (processed) perceptual act, and gave it its rich phenomenological content, includes the brain and the body of the soccer player, but also the terrain, the ball, the goal and the other players. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThe naïve view that projects these appearances onto some distal object (e.g. the naïve realist theory of colour), such that they have a "real look" is a confusion, much like any claim that distal objects have a "real feel" would be a confusion. There just is how things look to me and how things feel to you given our individual physiology.

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThe naïve view that projects these appearances onto some distal object (e.g. the naïve realist theory of colour), such that they have a "real look" is a confusion, much like any claim that distal objects have a "real feel" would be a confusion. There just is how things look to me and how things feel to you given our individual physiology.

It seems that many accept this at least in the case of smell and taste but treat sight as special, perhaps because visual phenomena are more complex than other mental phenomena and because depth is a quality in visual phenomena, creating the illusion of conscious experience extending beyond the body. But there's no reason to believe that photoreception is special, hence why I question the distinction between so-called "primary" qualities like visual geometry and so-called "secondary" qualities like smells and tastes (and colours).

Although even if I were to grant that some aspect of mental phenomena resembles some aspect of distal objects, it is nonetheless the case that it is only mental phenomena of which we have direct knowledge in perception, with any knowledge of distal objects being inferential, i.e. indirect, entailing the epistemological problem of perception and the viability of scepticism. — Michael

I don't think a realist about the colors of objects would say material objects have "real looks." Realists about colors acknowledge that colored objects look different to people with varying visual systems, such as those who are color-blind or tetrachromats, as well as to different animal species. Furthermore, even among people with similar discriminative color abilities, cultural and individual factors can influence how color space is carved up and conceptualized.

Anyone, whether a direct or indirect realist, must grapple with the phenomenon of color constancy. As illumination conditions change, objects generally seem to remain the same colors, even though the spectral composition of the light they reflect can vary drastically. Likewise, when ambient light becomes brighter or dimmer, the perceived brightness and saturation of objects remain relatively stable. Our visual systems have evolved to track the spectral reflectance properties of object surfaces.

It is therefore open for a direct realist (who is also a realist about colors) to say that the colors of objects are dispositional properties, just like the solubility of a sugar cube. A sugar cube that is kept dry doesn't dissolve, but it still has the dispositional property of being soluble. Similarly, when you turn off the lights (or when no one is looking), an apple remains red; it doesn't become black.

For an apple to be red means that it has the dispositional property to visually appear red under normal lighting conditions to a standard perceiver. This dispositional property is explained jointly by the constancy of the apple's spectral reflectance function and the discriminative abilities of the human visual system. Likewise, the solubility of a sugar cube in water is explained jointly by the properties of sugar molecules and those of water. We wouldn't say it's a naive error to ascribe solubility to a sugar cube just because it's only soluble in some liquids and not others.

The phenomenon of color constancy points to a shared, objective foundation for color concepts, even if individual and cultural factors can influence how color experiences are categorized and interpreted. By grounding color in the dispositional properties of objects, tied to their spectral reflectance profiles, we can acknowledge the relational nature of color while still maintaining a form of color realism. This view avoids the pitfalls of naive realism, while still providing a basis for intersubjective agreement about the colors of things. -

Luke

2.7k...a non hallucinatory experience of a distal object by definition requires the existence of a distal object. — flannel jesus

Luke

2.7k...a non hallucinatory experience of a distal object by definition requires the existence of a distal object. — flannel jesus

Glad you agree. In case you missed it, this "tautology" was in response to @Michael who holds the view that:

...distal objects are not constituents of experience. — Michael -

flannel jesus

2.9kI'm not seeing what you're seeing in that comment.

flannel jesus

2.9kI'm not seeing what you're seeing in that comment.

Distal objects being part of the casual history of an experience doesn't make them constituents of the experience, any more than shovels are constituents of holes.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum