-

Fooloso4

6.2kThere are two kinds of objects, concepts proper and pseudo-concepts. — RussellA

Fooloso4

6.2kThere are two kinds of objects, concepts proper and pseudo-concepts. — RussellA

'Object' is a pseudo-concept. A particular object is not.

(4.1272)So one cannot say, for example, ‘There are objects’, as one might say, ‘There are books’.

In our ordinary world, something that falls under a concept proper can also be a concept proper. — RussellA

Right, but the issue is whether something that falls under a pseudo-concept is a pseudo-concept. -

schopenhauer1

11kIE, I agree that Kant's Critique of Pure Reason makes more sense than Wittgenstein's Tracatus, although the Tractarian idea of modal worlds is very important in philosophy. — RussellA

schopenhauer1

11kIE, I agree that Kant's Critique of Pure Reason makes more sense than Wittgenstein's Tracatus, although the Tractarian idea of modal worlds is very important in philosophy. — RussellA

Curious your thoughts on this part:

Both can be communicated using symbols. One tells us about the state of affairs of the world, whether the case is true or false (synthetic-contingent, and experiential-empirical), and the other is necessary for language itself to function. Certainly, this could lead to a regress (definitions of definitions of definitions), and surely, at some point, it is simply just a matter of "knowing" the object is the object without any further explanation, but then we are getting into psychology, and NOT the "limits" of language. Surely I can point to these processes that account for object formation in the mind, and how we attach meaning to objects. And then, I have a "state of affairs" about how the mind KNOWS objects, and is not an infinite regress of definitions of the concept, but a theory of meaning that accounts for the concept-formation, and thus where language ends definitionally, I can continue on explanatorily with the psychology of concept-formation. — schopenhauer1

I am basically challenging Wittgenstein's project in Tractatus as the limits of language being actually "limits" the way he defines them (at some point you cannot say but show only). -

RussellA

2.6kCertainly, this could lead to a regress (definitions of definitions of definitions)....................Surely I can point to these processes that account for object formation in the mind, and how we attach meaning to objects. — schopenhauer1

RussellA

2.6kCertainly, this could lead to a regress (definitions of definitions of definitions)....................Surely I can point to these processes that account for object formation in the mind, and how we attach meaning to objects. — schopenhauer1

As I see it, some words we learn by description and some by acquaintance.

As regards learning by description, we can go to the dictionary and discover that a "tree" is defined as "a woody perennial plant having a single usually elongate main stem generally with few or no branches on its lower part". But then we have to look up the definition of "woody" and end up in an infinite regress.

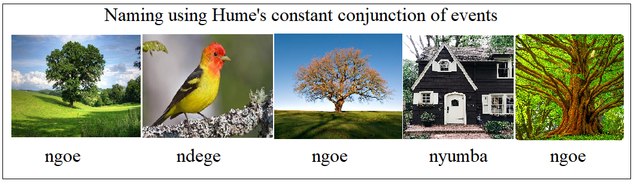

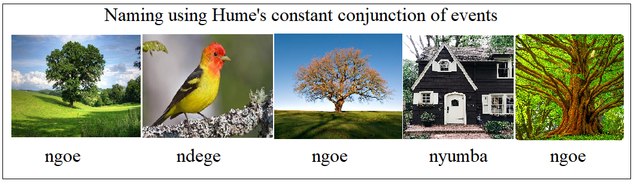

Sooner or later, we have to learn words by acquaintance, as illustrated in the picture below. As the Tractatus notes, I cannot describe the meaning of "ngoe", I can only show it. Though I agree that this is not the same approach as laid out in the Tractatus.

What do you think "ngoe" means, now you have been "shown" the picture? -

Fooloso4

6.2kYes a red toy car can picture a real red car, but the flaw in the Picture Theory is the statement "had to be stipulated", which has to happen outside the Picture Theory. — RussellA

Fooloso4

6.2kYes a red toy car can picture a real red car, but the flaw in the Picture Theory is the statement "had to be stipulated", which has to happen outside the Picture Theory. — RussellA

I don't see the problem. A proposition is a picture. A picture that makes use of both a visual and a propositional representation is still a picture.

Why cannot it be the case that wood pictures a truck, metal pictures a bicycle and marble pictures a car? — RussellA

It can. If the picture is intended to show the relative positions of a truck, a bicycle, and a car involved in an accident then a piece of wood. a piece of metal, and a marble can represent the situation. We make use of such pictures all the time.

There is no necessity that a red piece of wood pictures a red car, and yet the Picture Theory depends on this unspoken necessity, which seems to me to be a fundamental flaw in the Picture Theory. — RussellA

Just as the car does not become the bicycle, it is necessary that whatever it is the represents the car in the picture does not become something else. -

RussellA

2.6kJust as the car does not become the bicycle, it is necessary that whatever it is the represents the car in the picture does not become something else. — Fooloso4

RussellA

2.6kJust as the car does not become the bicycle, it is necessary that whatever it is the represents the car in the picture does not become something else. — Fooloso4

In the model is a red piece of wood, and in the world is a red car.

From the Picture Theory, the red piece of wood in the model pictures the red car in the world.

But how do we know, just from the picture itself, whether i) the red in the model is picturing the red in the world or ii) the wood in the model is picturing red in the world?

From the picture itself, we cannot know. We need someone to come along and tell us which is the case i) or ii), and if that happens, this destroys the Picture Theory, which is meant to stand alone. -

Fooloso4

6.2kFrom the picture itself, we cannot know. We need someone to come along and tell us which is the case i) or ii), and if that happens, this destroys the Picture Theory, which is meant to stand alone. — RussellA

Fooloso4

6.2kFrom the picture itself, we cannot know. We need someone to come along and tell us which is the case i) or ii), and if that happens, this destroys the Picture Theory, which is meant to stand alone. — RussellA

That depends on the medium of representation, whether what is being pictured is intended to communicate something to someone else, and what it is that is being represented.

(2.1)We picture facts to ourselves.

(2.11)A picture presents a situation in logical space, the existence and non-existence of states

of affairs.

(2.15)The fact that the elements of a picture are related to one another in a determinate way represents that things are related to one another in the same way.

Let us call this connexion of its elements the structure of the picture, and let us call the possibility of this structure the pictorial form of the picture. -

RussellA

2.6kThat depends on the medium of representation, whether what is being pictured is intended to communicate something to someone else, and what it is that is being represented............2.1 "we picture facts to ourselves" — Fooloso4

RussellA

2.6kThat depends on the medium of representation, whether what is being pictured is intended to communicate something to someone else, and what it is that is being represented............2.1 "we picture facts to ourselves" — Fooloso4

If we were only picturing facts to ourselves, then we are using a Private Language, which Wittgenstein in Philosophical Investigations said was not possible.

Even if we were picturing facts to ourselves, we would have to make the conscious choice whether i) the red in the model is picturing the red in the world or ii) the wood in the model is picturing red in the world.

If that were the case, a picture wouldn't be a model of reality, a picture would be a model of an individual's conscious decisions.

2.12 "A picture is a model of reality" -

schopenhauer1

11kWhat do you think "ngoe" means, now you have been "shown" the picture? — RussellA

schopenhauer1

11kWhat do you think "ngoe" means, now you have been "shown" the picture? — RussellA

So is this illustration supposed to be showing a potential "theory" of cognition for words associated with objects? If so this itself would be an illustration of a "psychological theory" that goes beyond simply "acquaintance" (showing) the object, thus refuting that "acquaintance" or "showing" is where it must stop. Actually, it can go further into explanatory theory- whether that be Hume's constant conjunctions, Kant's Transcendental Idealism, or modern cognitive neuroscientific theories! -

RussellA

2.6k'Object' is a pseudo-concept. A particular object is not. — Fooloso4

RussellA

2.6k'Object' is a pseudo-concept. A particular object is not. — Fooloso4

'Object' is a pseudo-concept because it says nothing about what is the case, not because it makes up the substance of the world. — Fooloso4

Right, but the issue is whether something that falls under a pseudo-concept is a pseudo-concept. — Fooloso4

Tractarian objects are pseudo-concepts

Introduction - "This amounts to saying that “object” is a pseudo-concept. To say "x is an object" is to say nothing".

Why is a Tractarian object a pseudo-concept? Things can be said about concepts proper, such as book and tables, but things cannot be said about Tractarian objects because they are simples. They are pseudo-concepts because they are simples.

2.02 "Objects are simple"

Why are Tractarian objects simples? If they weren't simples, propositions could not picture the world.

2.021 "Objects make up the substance of the world. That is why they cannot be composite

2.0211 "If the world had no substance, then whether a proposition had sense would depend on whether another proposition was true

2.0212 "In that case we could not sketch any picture of the world (true or false)

2.023 "Objects are just what constitute the unalterable form"

Therefore as Tractarian objects (ie, pseudo-concepts) are simples (ie, indivisible), there cannot be anything that falls under them.

===============================================================================

Formal concepts are pseudo-concepts. — Fooloso4

Tractarian objects are pseudo-concepts

Introduction - "This amounts to saying that “object” is a pseudo-concept. To say "x is an object" is to say nothing".

The proposition "x is a horse" is a concept proper and the proposition "x is a number" is a formal concept.

(Spark notes Propositions 4.12 – 4.128)

Examples of propositional variables could be: "the sky is blue", "the sky is purple", "grass is green", "grass is orange".4.127 "The propositional variable signifies the formal concept"

Being propositional variables, each has the value either true or false.

In the truth table, "the sky is blue" is true, "the sky is purple" is false, "grass is green" is true, "grass is orange" is false.

Therefore the propositional variable "x is a number" signifies a formal concept.

What does Wittgenstein mean by formal? He refers to formal relations, which are logical relations between objects. He refers to formal properties, which are internal and logical. Formal means logical.

4.122 "In a certain sense we can talk about formal properties of objects and states of affairs, or, in the case of facts, about structural properties: and in the same sense about formal relations and structural relations. (Instead of "structural property" I also say "internal property": instead of "structural relation", "internal relation")

The variable name x signifies a pseudo-concept object

4.1272 "Thus the variable name "x" is the proper sign for the pseudo-concept object. Whenever the word "object" ("thing". etc) is correctly used, it is expressed in conceptual notion by a variable name"

On the one hand the propositional variable "x is a number" signifies a formal concept and on the other hand the variable x signifies a pseudo-concept object. Therefore, a formal concept cannot be a pseudo-concept. -

schopenhauer1

11kOn the one hand the propositional variable "x is a number" signifies a formal concept and on the other hand the variable x signifies a pseudo-concept object. Therefore, a formal concept cannot be a pseudo-concept. — RussellA

schopenhauer1

11kOn the one hand the propositional variable "x is a number" signifies a formal concept and on the other hand the variable x signifies a pseudo-concept object. Therefore, a formal concept cannot be a pseudo-concept. — RussellA

Even this on the face of it seems odd to call a "pseudo-concept". Why can't it just be a concept that represents possibilities of states of affairs? And what about "Blue unicorns where hats on Tuesdays"? That is a pseudo-concept / proposition?

And even if it is, so what? This is similar to the problem of Russell, "The present King of France is Bald".

By empirical means, this sentence is about an imaginary or made-up class of characters. That is still a class of things, a kind of concept. Does Wittgenstein allow for that, if he is "object-agnostic" (he doesn't elaborate on what an object is in any significant metaphysical description)?

And what about "concepts" like "processes"? It's arguable that "processes" like "evolution" don't really "exist" but are groupings of how we identify the world as to what happens to objects. "Evolution" itself may not be a "thing" in the world per se, but a descriptor of a series of phenomena that is grouped together by humans for explanatory power. -

RussellA

2.6kIf so this itself would be an illustration of a "psychological theory" that goes beyond simply "acquaintance" (showing) the object, thus refuting that "acquaintance" or "showing" is where it must stop. — schopenhauer1

RussellA

2.6kIf so this itself would be an illustration of a "psychological theory" that goes beyond simply "acquaintance" (showing) the object, thus refuting that "acquaintance" or "showing" is where it must stop. — schopenhauer1

I agree that explaining how the mind can learn the meaning of the world "ngoe" from just five pictures is beyond my pay grade. All I know is that it works, and is in principle very simple.

The Tractatus only begins after I have learnt the word "ngoe", and only then, does the word "ngoe" in language mirror the "ngoe" in the world. -

schopenhauer1

11kI agree that explaining how the mind can learn the meaning of the world "ngoe" from just five pictures is beyond my pay grade. All I know is that it works, and is in principle very simple.

schopenhauer1

11kI agree that explaining how the mind can learn the meaning of the world "ngoe" from just five pictures is beyond my pay grade. All I know is that it works, and is in principle very simple.

The Tractatus only begins after I have learnt the word "ngoe", and only then, does the word "ngoe" in language mirror the "ngoe" in the world. — RussellA

Sure, but then, why make a theory that limits language thus in such a way with how he treats language, objects, concepts, propositions, etc.? Don't these types of explanatory things that go "beyond" mere showing refute his claims on the limits of language? -

Fooloso4

6.2kIf we were only picturing facts to ourselves, then we are using a Private Language — RussellA

Fooloso4

6.2kIf we were only picturing facts to ourselves, then we are using a Private Language — RussellA

First, we do not only picture facts to ourselves. Second, even if we did that would not be a private language unless no one else could understand it and what is pictured is something no one else could be aware of.

Even if we were picturing facts to ourselves, we would have to make the conscious choice whether i) the red in the model is picturing the red in the world or ii) the wood in the model is picturing red in the world. — RussellA

The picture that comes to mind need not be the result of conscious choice. With regard to the model of the accident the color of the car has no bearing on what is being depicted. What a picture represents is a logical relation:

A picture presents a situation in logical space, the existence and non-existence of states of affairs.

(2.11) — Fooloso4

They are pseudo-concepts because they are simples.

2.02 "Objects are simple" — RussellA

'Object' is a pseudo-concept but not all objects are simple objects. Spatial objects such as a chairs tables, and books ( 3.1431) are not simple objects.

On the one hand the propositional variable "x is a number" signifies a formal concept and on the other hand the variable x signifies a pseudo-concept object. Therefore, a formal concept cannot be a pseudo-concept. — RussellA

'x' is the variable name for the pseudo concept 'number'. (4.1272) Substituting "a number" for 'x' gives us: "Number is a number" which is nonsense. The variable name 'x' cannot be used for both the pseudo-concept 'number' and 'a number'. -

RussellA

2.6kEven this on the face of it seems odd to call a "pseudo-concept"...And what about "concepts" like "processes"? — schopenhauer1

RussellA

2.6kEven this on the face of it seems odd to call a "pseudo-concept"...And what about "concepts" like "processes"? — schopenhauer1

There are two distinct worlds. There is our ordinary world with concepts proper and objects like books, tables and mountains. There is the Tractarian world with pseudo-concepts and objects that are simples and indivisible.

Objects such as blue, unicorn and hat and concepts such as processes and evolution are not referred to in the Tractatus as they are concepts proper in ordinary language and the Tractatus is not dealing with ordinary language.

Another reason that concepts such as process and evolution are not referred to in the Tractatus is that they are abstract concepts, such as angst and beauty, which can neither be described nor shown. Only concrete concepts such as blue, unicorn and hat that can be either described or shown.

A proposition such as "unicorns wear hats" is an ordinary language proposition. In the Tractatus, the propositions Wittgenstein is referring to have the form fx

4.24 "I write elementary propositions as functions of names, so that they have the form "fx", ∅(x,y)", etc."

It may be convenient to try to understand the Tractatus using ordinary language propositions such as "grass is green", but only as an analogy, as one tries to understand gravity by picturing a ball on a sheet of rubber.

However the Tractatus is philosophically important in beginning to develop the idea of modal worlds, possible worlds, where we can sensibly talk about non-existent things like unicorns and Sherlock Holmes, something that Bertrand Russell had problems with.

Anyway, I am off on holiday, but want to say that I have learnt a lot from this thread. -

RussellA

2.6kFirst, we do not only picture facts to ourselves. — Fooloso4

RussellA

2.6kFirst, we do not only picture facts to ourselves. — Fooloso4

I look and see a fact in the world such as "the apple is on the table". As no-one else can see into my mind, in that telepathy is not a thing. I can only picture facts to myself.

===============================================================================2.1 "we picture facts to ourselves"

The picture that comes to mind need not be the result of conscious choice. With regard to the model of the accident the color of the car has no bearing on what is being depicted. What a picture represents is a logical relation: — Fooloso4

In the model is a red piece of wood and in the world is a red car.

I agree that when I see the colour red, I have no conscious choice as to what colour I see, in that I cannot choose to see another colour, such as blue or green.

I agree that there is a logical relation between the red piece of wood in the model and the red car in the world.

But who knows what these logical relations are. These logical relations cannot be determined by the picture alone.

For example, is the logical relation between the red in the model and the red in the world (in that the red in the model pictures the red in the world) or is the logical relation between the red in the model and the car in the world (in that the red in model pictures the car in the world).

Within the same picture can be innumerable logical relations.

===============================================================================

'Object' is a pseudo-concept but not all objects are simple objects. Spatial objects such as a chairs tables, and books ( 3.1431) are not simple objects. — Fooloso4

Objects such as chairs, tables and books are not Tractarian objects. These are objects in ordinary language. and the Tractatus is not dealing with ordinary language.

The key word is "imagine". Wittgenstein is using an analogy. He is not saying that tables, chairs and books are Tractarian objects.3.1431 "The essence of a propositional sign is very clearly seen if we imagine one composed of spatial objects (such as tables, chairs, and books) instead of written signs.

===============================================================================

'x' is the variable name for the pseudo concept 'number'. (4.1272) Substituting "a number" for 'x' gives us: "Number is a number" which is nonsense. The variable name 'x' cannot be used for both the pseudo-concept 'number' and 'a number'. — Fooloso4

Exactly. As Bertrand Russell writes in the introduction, to say "x is an object" is to say nothing. As he says, meaningless.

To say “x is an object” is to say nothing. It follows from this that we cannot make such statements as “there are more than three objects in the world”, or “there are an infinite number of objects in the world”.

The proposition "x is a number" is a Formal Concept. Formal means logical. It is the whole proposition that is the Formal Concept, because the Formal Concept establishes the relations between its parts, "x" and "number".

4.127 "The propositional variable signifies the formal concept"

"Number" is a pseudo-concept

Introduction "This amounts to saying that “object” is a pseudo-concept."

The variable name "x" is a sign that signifies a number, such that "x is a number".

In the proposition "x is a number", we could substitute "x" by "x is a number" giving the proposition "x is a number is a number". Continuing "x is a number is a number is a number". But this becomes meaningless. Therefore, in the proposition "x is a number", there must be an identity between "x" and "number", meaning that if "number" is a pseudo-concept then "x" must also be a pseudo concept.

Therefore both "x" and "number" are pseudo concepts. The proposition "x is a number" is a Formal Concept.

I am off on holiday, but have appreciated the conversational research about the Tractatus. -

Fooloso4

6.2kI look and see a fact in the world such as "the apple is on the table". As no-one else can see into my mind, in that telepathy is not a thing. I can only picture facts to myself. — RussellA

Fooloso4

6.2kI look and see a fact in the world such as "the apple is on the table". As no-one else can see into my mind, in that telepathy is not a thing. I can only picture facts to myself. — RussellA

The proposition "the apple is on the table" is a picture of the apple on the table.

But who knows what these logical relations are. These logical relations cannot be determined by the picture alone. — RussellA

The logical relation of the model to the car? It is a representation, a picture, of it. If I don't know what it it represents I may not know it from seeing the red piece of wood, but I might not know that even a life-sized model with an actual red car of the same make and model represents the accident.

Within the same picture can be innumerable logical relations. — RussellA

Yes, and it is possible that some picture can represent all of them.

Objects such as chairs, tables and books are not Tractarian objects. These are objects in ordinary language. and the Tractatus is not dealing with ordinary language. — RussellA

They are not the objects that make up the substance of the world. They are, however, objects talked about in the Tractatus. The pseudo-concept 'object' covers both.

3.1431 "The essence of a propositional sign is very clearly seen if we imagine one composed of spatial objects (such as tables, chairs, and books) instead of written signs.

The key word is "imagine". Wittgenstein is using an analogy. He is not saying that tables, chairs and books are Tractarian objects. — RussellA

The key words are "propositional sign", that is, the variable 'x'.

the Formal Concept establishes the relations between its parts, "x" and "number". — RussellA

'x' is the "name" of the formal concept 'number'.

if "number" is a pseudo-concept then "x" must also be a pseudo concept. — RussellA

The variable name 'x' is not a concept.

The same [as applies to 'object] applies to the words ‘complex’, ‘fact’, ‘function’, ‘number’, etc.

They all signify formal concepts, and are represented in conceptual notation by variables ...

'x' or some other variable is how formal or pseudo-concepts such as 'object' and 'number' are represented in a proposition. -

schopenhauer1

11kObjects such as blue, unicorn and hat and concepts such as processes and evolution are not referred to in the Tractatus as they are concepts proper in ordinary language and the Tractatus is not dealing with ordinary language.

schopenhauer1

11kObjects such as blue, unicorn and hat and concepts such as processes and evolution are not referred to in the Tractatus as they are concepts proper in ordinary language and the Tractatus is not dealing with ordinary language.

Another reason that concepts such as process and evolution are not referred to in the Tractatus is that they are abstract concepts, such as angst and beauty, which can neither be described nor shown. Only concrete concepts such as blue, unicorn and hat that can be either described or shown. — RussellA

Again, these distinctions between "concept", "formal concept", and "pseudo-concept", I know come from the broader analytic hay-making of only looking at language, and not the psychology behind the language. This is why I think Kant is much more interesting, as he actually not only covers these various issues with great rigor (especially his analytic-synthetic distinction), he goes on to explain how it is that both of these understandings of reality come about. He is widening the field of explanation, not limiting it. And thus I find this early 20th century positivist-analytic anti-metaphysics/epistemology distasteful and cloyingly more arrogant than the usual philosopher's arrogant schtick (they killed you Socrates for asking too many questions...and possibly siding with Sparta...!!).

We have psychology, neuroscience, anthropology, biology, and a whole host of other scientific and humanistic disciples that can explain how language might possibly work, the psychology behind concept formation, etc. Many "theories" (like evolution), are groupings of phenomenon for explanatory power, yet they are real. I don't see Wittgenstein's "state of affairs" as even encompassing these kind of meta-understandings of the world. "Evolution is the mechanism of biological change in species". That statement according to Witt, would probably be some kind of "pseudo-concept". Ridiculous. -

013zen

164Few...been out of town for a bit, and it seems I’ve missed a lot. A quick glance of the topics is interesting, and a lot to consider. I like a lot of the manners in which RussellA considers the ideas, but there are a few things here and there that I don’t think are quite right...I generally think the manner in which you’re thinking is fruitful, though. So, thank you...I'll try and work through it more.

013zen

164Few...been out of town for a bit, and it seems I’ve missed a lot. A quick glance of the topics is interesting, and a lot to consider. I like a lot of the manners in which RussellA considers the ideas, but there are a few things here and there that I don’t think are quite right...I generally think the manner in which you’re thinking is fruitful, though. So, thank you...I'll try and work through it more.

I think Fooloso4 does a good job of raising some of the issues I have, as well as more I hadn't considered. I'll have to work through the discussion a bit.

While I firmly believe that you’re right – that in order to fully appreciate what's going on with a lot of the ideas in the Tractatus, that a familiarity with Kant is particularly helpful – I don’t agree that the analytic tradition was, in some sense, a watered down version of many of the ideas we see developed in Kant, though.

These thinkers were responding to Kant; this is why the neo-kantian movement finds its roots at this time in thinkers like Helmholtz, despite him being primarily a physicist.

Again, I really think its best to consider the discussion as part of, well, a discussion; not some philosopher or scientist screaming into a vacuum.

The question that scientists had been asking, at least, as far back as Francis Bacon was: “Can metaphysics supply us with genuine knowledge?”

That is:

“Can we know why something occurs, and not simply how it occurs?”

Hume answered: “No.”

Genuine knowledge only comes to us via the senses. We can only ever say how things happen, and never why. Therefore, we can never be certain of any of our knowledge, because despite seeing something a hundred times, it could always be the case that I am ignorant of the true inner workings of the phenomena, and in fact, it only repeats a certain pattern 100 times before evolving into some other pattern.

Kant didn’t like this. He thought we could have genuine metaphysical knowledge.

Kant answered the question: “Yes. We can know why things occur, and therefore be certain about them.”

Yes, we do gain knowledge through the senses, but this knowledge is a synthesis of empirical data that is categorized by the mind via independently existing mental structures. An internal logic, if you will, that orders and categorizes information we gain from experience. This is how we can be certain of things like “Cause and effect” and “1+1=2”.

This was awesome, but left us in a position where we could never untangle reality from what we supply. Sure, we could have certainty regarding why things occurred, but we could never know to what extent we are right regarding our picture of the world.

Hegel (I think) had a clever idea...basically, borrowing from Hume’s copy principle, he said we copy direct aspects of reality, but categorize and manipulate them with an inherent logic which we can study, isolate, and thereby know what exactly the mind supplies of experience. What remains will be reality, or the supposedly unknowable reality Kant left us with.

This was cut short, however, when studies during the tail end of the 1800s showed that we do not, in fact, copy reality in any sense. We translate the experience via sensory organs into electrical signals that are then reinterpreted by the brain. We could show, for example, that by stimulating specific nerves via controlled electric shocks, we could cause patients to “see” light where there wasn’t any.

This caused the “back to Kant” movement during the early 1900s.

This is why Mach starts trying to consider how we might break up ideas into elements which constitute them without appealing to atoms.

Which sets the stage for the neo-positivism / neo-kantian debate during the 1900s.

Witt’s Tract is certainly responding to this since he no doubt was familiar with the debate via Russell. Insofar as I don’t consider him to be sympathetic to the neo-positivism angle, I do wonder if the work can be read in a neo-kantian light? My tertiary knowledge leads me to think that Witt is trying to bridge the gap, somehow, but I cannot be certain of this.

Really interesting ideas....i'll have to catch up more when I have time. -

Fooloso4

6.2kAre the simply objects that make up the substance of the world knowable? Wittgenstein says:

Fooloso4

6.2kAre the simply objects that make up the substance of the world knowable? Wittgenstein says:

(2.0123)If I know an object I also know all its possible occurrences in states of affairs.

(Every one of these possibilities must be part of the nature of the object.)

A new possibility cannot be discovered later.

He continues:

(2.01231)If I am to know an object, though I need not know its external properties, I must know all

its internal properties.

And:

(2.0124)If all objects are given, then at the same time all possible states of affairs are also given.

Can we know that all objects are given? Can we know all possible states of affairs? At best we can know what states of affairs have occurred. But actual states of affairs are not the only states of affairs that are possible. If that were the case nothing new could occur.

Without making it explicit Wittgenstein has drawn a limit to human knowledge. This limit is distinct from that of what can be said and what is shown. -

schopenhauer1

11k

schopenhauer1

11k

And what about scientific ideas like "evolution" that require clues from nature, and are not "states of affairs" of the world, but a combining of phenomena into a concept of how not "what" is happening? To me, Early Witt would just say that this kind of explanatory evidence is not suitable for logical analysis so has to be considered a pseudo-concept. But that seems at odds with how science works, which is by not just observing "states of affairs", but creating explanations from the "states of affairs" of various experiments.

At the end of the day, it seems like Tractatus gives us an interesting computer coding framework. What you can do with his ideas is create a neat coding language from it. I can probably map out Tractatus claims to "constants" and "variables" and "boolean", syntax errors, undefined variables, and such from his propositions of linguistic analysis- and as it works for that purpose, it is fine and dandy.

However, as it is trying to actually picture the "world" and "reality" (not just be an internal guide for parsing out terms in a language), it falls short. And I am not saying that Kant is RIGHT or has captured THE TRUTH. But rather, I see Kant as actually doing epistemology while Witt is doing proto-programming. That is to say Witt might be coherent within the system he defines thusly, but it's explanatory power for how his claims map onto the world is anemic. That is to say, there is nothing really doing this corresponding. There is nothing putting the claims to the world as to how this occurs. It doesn't have to be Kantian, but it does have to be explanatory as far as how the epistemology operates and works. This is not done, so there is no "picture theory". Objects are ill-explained. How the mind creates objects, observes objects, observes cause and effect, are given short shrift, etc. It is coherentism looking to be correspondence theory. -

013zen

164

013zen

164

I take your point, and I think looking at one side of the work, there are a lot of questions on can bring to bear. There is good reason to wonder whether the analytic project as a whole was a misguided effort, despite seeming reasonable at its roots.

But, considering your point, and reading other remarks that Witt makes, I'm beginning to get the sense that, perhaps, he was critiquing that very project.

I think that Fooloso4 put it well when they pointed out:

Can we know that all objects are given? Can we know all possible states of affairs? At best we can know what states of affairs have occurred. But actual states of affairs are not the only states of affairs that are possible. If that were the case nothing new could occur.

Without making it explicit Wittgenstein has drawn a limit to human knowledge. This limit is distinct from that of what can be said and what is shown. — Fooloso4

Witt. seems to ultimately say that one cannot provide all the elementary propositions apriori; because you can never predict beforehand if you'll find yourself in a situation which needs a new sign. The world is logical, and human logic mirrors its form; we cannot say what that form is though. We cannot even think it. So, regarding epistemology we're limited to only possibilities we can think, but things could always turn out otherwise.

Concepts like "evolution" are one possible description of the world - we can arrange things in this way; but this is only one possible description, and we could always discover some new, better, description. We can, however, be certain that it will make sense, once given all the pieces; it will be logically in order.

All the point about the elementary propositions is now left in such state that all they can accomplish is, perhaps, as you've said: useful for making sure that scientific discourse is culled of unnecessary signs ...that is, they are simply a useful tool, but one cannot glean anything meaningful from them, because there could always be more. Science is meant to discover the states of affairs, first, for which the elementary propositions will follow insofar as if we understand anything it must be logical, and our language will mirror that logic when we attempt to express our ideas. We will always be able to analyze language and eliminate unnecessary signs, better displaying the logic that was always present, but this comes after the fact.

I'll just end with this quote from the work that I think is helpful insofar as its not technical, and also that it seems to express a general sentiment that Witt wanted to express for the work:

"All propositions of our colloquial language are actually, just as they are, logically completely in order. That most simple thing which we ought to give here is not a simile of truth but the complete truth itself.

(Our problems are not abstract but perhaps the most concrete that there are)" (5.5563).

We cannot abstract our problems away. We are always in a situation where we are forced to adopt the best picture we have of the world, and furnish the objects accordingly. Analysis cannot show whether you've got the right description, only whether the picture is logically in order. -

Fooloso4

6.2kBut, considering your point, and reading other remarks that Witt makes, I'm beginning to get the sense that, perhaps, he was critiquing that very project. — 013zen

Fooloso4

6.2kBut, considering your point, and reading other remarks that Witt makes, I'm beginning to get the sense that, perhaps, he was critiquing that very project. — 013zen

He was. But since he did so using their language it may seem as though he is in agreement with them.

Concepts like "evolution" are one possible description of the world — 013zen

A couple of remarks from Wittgenstein:

Do I want to say, then, that certain facts are favorable to the formation of certain concepts; or again unfavorable? And does experience teach us this? It is a fact of experience that human beings alter their concepts, exchange them for others when they learn new facts; when in this way what was formerly important to them becomes unimportant, and vice versa. (It is discovered e.g. that what formerly counted as a difference in kind, is really only a difference in degree. (Zettel 352)

He accepts that there are facts, but facts do not determine concepts.

Elsewhere:

(CV 18)What a Copernicus or a Darwin really achieved was not the discovery of a new true theory but a fertile point of view.

The larger issue for Wittgenstein is ways of seeing, seeing aspects, "seeing as". The "fertile point of view" of "a Copernicus or a Darwin" is a conceptual revolution, the displacement of the Earth as the center or the rejection of kinds in favor of variations. We do not simply see things as they are but according to the way we represent or picture them. -

schopenhauer1

11kWe do not simply see things as they are but according to the way we represent or picture them. — Fooloso4

schopenhauer1

11kWe do not simply see things as they are but according to the way we represent or picture them. — Fooloso4

How would this be different thank Kant or Plato for that matter?

One main difference is he’s using language parsing to explain epistemology. That’s like me saying that you got a coding error because you didn’t follow the correct syntax from the Programming language I created. I could’ve created a different language with a different syntax where that error didn’t occur, but according to the Tractatus and Wittenstein’s view, these errors occur. Notice, this isn’t how necessarily reality works just how his programming language (I.e. his Tractatus claims) works, which he uses to somehow describe the limits of reality. I just don’t buy it.

Not following a certain limited programming, syntax isn’t how epistemology works. Kant was explaining how various epistemological reasoning occurred. Cognitive science does the same. Anthropological evolutionary science does the same. None of them need rely on syntax errors of language parsing. Writing bad code is not an epistemology. Acting as if epistemology is writing code that is not in the correct syntax is not an epistemology. And yes, I believe that Tractaus is the rules for basically writing some programming language (pretending to be some key to the limits of what we can say about reality). -

Fooloso4

6.2kHe is not explaining epistemology. He is saying that logic is a transcendental condition for epistemology.

Fooloso4

6.2kHe is not explaining epistemology. He is saying that logic is a transcendental condition for epistemology.

but according to the Tractatus and Wittenstein’s view, these errors occur. — schopenhauer1

It is, rather, according to your misrepresentation of Wittgenstein's view in the Tractatus. -

schopenhauer1

11kHe is not explaining epistemology. He is saying that logic is a transcendental condition for epistemology. — Fooloso4

schopenhauer1

11kHe is not explaining epistemology. He is saying that logic is a transcendental condition for epistemology. — Fooloso4

Wittenstein is not a god to me he could be wrong. Schopenhauer could be wrong can could be wrong. All of them could be wrong. He’s trying to say that certain things cannot be stated clearly in language. He’s using the methods of a programmer to do this in my opinion. This isn’t Explaining anything. It is just limiting language using language, parsing, syntax errors and such. It is making claims on EPISTEMOLOGY without EXPLAINING IT.

Is Aristotle correct on the definition of a human because he wrote a passage in a book on it and that book is studied in philosophy? -

Fooloso4

6.2kWittenstein is not a god to me he could be wrong. — schopenhauer1

Fooloso4

6.2kWittenstein is not a god to me he could be wrong. — schopenhauer1

Of course he could! But you being wrong about him is still wrong. -

schopenhauer1

11kOf course he could! But you being wrong about him is still wrong. — Fooloso4

schopenhauer1

11kOf course he could! But you being wrong about him is still wrong. — Fooloso4

Ah yes the old, YOU DONT UNDERSTAND HIM game. I could also write some stuff and then say that you just don’t understand it and continually do it so that I am always at an advantage whereby whatever I wrote is correct and whatever your interpretation of it is incorrect. And somebody who I just like his interpretation of what I wrote will be correct while yours will always be incorrect. it’s a bullshit game. quit it.

Wittenstein wasn’t writing unambiguous shit. It’s clearly ambiguous to the point that even people who knew him best, including Russell didn’t quite understand it he thought.

Go fanboy yourself. -

Fooloso4

6.2k

Fooloso4

6.2k

I will try again. You said;

His definition is like one in computer programming it seems:

"From Gemini: General purpose: More broadly, an object can simply refer to a variable, a data structure, or even a function. In this sense, it's a way to organize data in memory and refer to it using an identifier (like a name)."

That is to say, it is a logical marker, a name. But then what's the use of distinguishing objects and atomic facts if you leave objects so undefined? You mine as well just start with atomic facts.. — schopenhauer1

An object does not refer to a variable. A variable can be used, however, to refer to an object. The term 'object' is not a particular object. It is analogous to a number. The term 'number' is not a particular number,

that is why we use variables such a 'n' or 'x' where no specific number or object is specified.

An object in not a data point. Data points do not make up the substance of the world.

Simple objects do.

An object is not a function. The possibility of and ways in which simple objects combine is determined by those objects themselves.

An object is not a way of organizing data. Objects are self-organizing in that the possibilities of combining are build into the objects.

Objects are not in memory. They subsist independently of what is the case.

An object is not a logical marker. It is a substantive thing.

An object is not a name. It is what is named in an elementary proposition.

None of this is a matter of what I say being right or wrong. It can all be supported and has been supported in this thread by reference to the text. -

schopenhauer1

11kI will try again. You said; — Fooloso4

schopenhauer1

11kI will try again. You said; — Fooloso4

You tried?

Simple objects do. — Fooloso4

Which are....???

An object is not a function. The possibility of and ways in which simple objects combine is determined by those objects themselves. — Fooloso4

Why would that be the case being that we don't have any idea what objects are other then they are "simples"? Why would it be the objects themselves that determine it and not some other factor of relations? But here further investigation, commentary, etc. is needed. Not opaque statements..."Thus spake Zarathustra!".

An object is not a way of organizing data. Objects are self-organizing in that the possibilities of combining are build into the objects. — Fooloso4

Why? How? What views is this set against?

Objects are not in memory. They subsist independently of what is the case. — Fooloso4

How do we know? What are some reasons for at least, strongly believing this?

None of this is a matter of what I say being right or wrong. It can all be supported and has been supported in this thread by reference to the text. — Fooloso4

But is it supportable, whether or not Wittgenstein believed it or not?

These claims are without explanation as far as I see. Now, I believe strongly in comparing styles and content to show if and where there is an insufficient account of explanation for one's exposition on one's worldview. Well, where is the explanation for any of this other than supposition and possibly because "The rest of my beliefs won't work if these initial claims don't hold"? Having your theory not be coherent if it isn't the case, is not a case in itself for somethings soundness, though certainly validity. This is why I said that it is very much like a programmer writing a language setting out how the language will operate so that it doesn't run into errors.

How is it that objects are the building blocks for atomic facts? Why should there even be atomic facts? Why is objects the building blocks and not processes? This is all strange to simply "Thus claim...".

You can say to me, "Because it has to stop somewhere". Sure, but imagine if any other thinker said that he doesn't have to explain themselves any further.. It just seems like a strange thing to NOT demand from a thinker trying to give you such a comprehensive take on the world. And I would suspect that any modern, living thinker would be grilled to death with more questions to answer for, and the work would NOT just stand on its own to have fanboys be gatekeepers for the deep mysteries of the great Witty.

Now let's compare this to a radically different thinker (from the same time period), Alfred North Whitehead:

4] With the purpose of obtaining a one-substance cosmology, 'prehensions'

are a generalization from Descartes' mental 'cogitations,' and from

Locke's 'ideas,' to express the most concrete mode of analysis applicable

to every grade of individual actuality. Descartes and Locke maintained a

two-substance ontology-Descartes explicitly, Locke by implication. Descartes, the mathematical physicist, emphasized his account of corporeal

substance; and Locke, the physician and the sociologist, confined himself

to an account of mental substance. The philosophy of organism, in its

scheme for one type of actual entities, adopts the view that Locke's account of mental substance embodies, in a very special form, a more penetrating philosophic description than does Descartes' account of corporeal

substance. Nevertheless, Descartes' account must find its place in the

philosophic scheme. On the whole, this is the moral to be drawn from

the Monadologyt of Leibniz. His monads are best conceived as generalizations of contemporary notions of mentality. The contemporary notions

of physical bodies only enter into his philosophy subordinately and derivatively. The philosophy of organism endeavours to hold the balance more

evenly. But it does start with a generalization of Locke's account of mental

operations. — Process and Reality- A.N. Whitehead

Notice the author explains, detail, what his terms mean, provides some context, etc. Or here:

Or just look at Kant:

Of time we cannot have any external intuition, any more than we can have an internal intuition of space. What then are time and space? Are they real existences? Or, are they merely relations or determinations of things, such, however, as would equally belong to these things in themselves, though they should never become objects of intuition; or, are they such as belong only to the form of intuition, and consequently to the subjective constitution of the mind, without which these predicates of time and space could not be attached to any object? In order to become informed on these points, we shall first give an exposition of the conception of space. By exposition, I mean the clear, though not detailed, representation of that which belongs to a conception; and an exposition is metaphysical when it contains that which represents the conception as given à priori.

1. Space is not a conception which has been derived from outward experiences. For, in order that certain sensations may relate to something without me (that is, to something which occupies a different part of space from that in which I am); in like manner, in order that I may represent them not merely as without, of, and near to each other, but also in separate places, the representation of space must already exist as a foundation. Consequently, the representation of space cannot be borrowed from the relations of external phenomena through experience; but, on the contrary, this external experience is itself only possible through the said antecedent representation. — Kant- Critique of Pure Reason

Notice here Kant EXPLAINS his reasoning. Even if you disagree with his premise, he gives why he thinks what he thinks.

The world is everything that is the case.*

1.1 The world is the totality of facts, not of things.

1.11 The world is determined by the facts, and by these being all the

facts.

1.12 For the totality of facts determines both what is the case, and

also all that is not the case.

1.13 The facts in logical space are the world.

1.2 The world divides into facts.

1.21 Any one can either be the case or not be the case, and everything

else remain the same.

2 What is the case, the fact, is the existence of atomic facts.

2.01 An atomic fact is a combination of objects (entities, things).

2.011 It is essential to a thing that it can be a constituent part of an

atomic fact.

2.012 In logic nothing is accidental: if a thing can occur in an atomic

fact the possibility of that atomic fact must already be prejudged

in the thing.

2.0121 It would, so to speak, appear as an accident, when to a thing

that could exist alone on its own account, subsequently a state

of aairs could be made to t.

If things can occur in atomic facts, this possibility must already lie in them. — Tractatus

No exposition. No context. No justification. We just accept that these statements must be true without why, how, what for, etc. It builds from there, but from what epistemic foundation other than fiat of the author? "Entities and things" are also extremely vague, yet even this can be somewhat forgiven if it's explained. But its vagueness is not explained ("This is purposely left vague by me, the author, because...??""")

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum