-

Luke

2.7kWe've no apparent biological reason to group the various neural goings on in the way we do. No reason to have the collection 'smelling coffee' at all, other than for communication. — Isaac

Luke

2.7kWe've no apparent biological reason to group the various neural goings on in the way we do. No reason to have the collection 'smelling coffee' at all, other than for communication. — Isaac

In addition to communication, what’s common to many instances of the collection ‘smelling coffee’ is the smelling of coffee. -

Isaac

10.3kIn addition to communication, what’s common to many instances of the collection ‘smelling coffee’ is the smelling of coffee. — Luke

Isaac

10.3kIn addition to communication, what’s common to many instances of the collection ‘smelling coffee’ is the smelling of coffee. — Luke

That argument is circular. If you decide that some collection of neural activity is called 'smelling coffee' then obviously 'smelling coffee' is going to then be common to all, you defined it that way.

If I say "all these items in front of me are going to be called 'bob'" it's not a further discovery that they share to say "hey, they're all called 'bob'". Of course they are, I just declared it so. -

Mww

5.4kI think maybe my poor writing is creating some confusion — Isaac

Mww

5.4kI think maybe my poor writing is creating some confusion — Isaac

Yeah, maybe me too. I didn’t mean, and I didn’t take you to mean either, by one-to-one correspondence that for each sensation there is only one network by which the brain tells us about it. Makes sense, though, that sommeliers may have the ability to reduce or localize correspondences closer to one-to-one, if it is true they can distinguish all those minor sensations contained in the major. I dunno….I can’t do it myself.

On the other hand, it seems like there must be some method by which a sip of this liquid gives the experience with this name, and no other, which is a form of one-to-one correspondence. And while it may indeed be a language condition that says this sensation is of coffee and not gasoline, it is hard for me to understand why the brain needs coffee or gasoline to inform that one sensation is not like the other.

————-

We've no apparent biological reason to group the various neural goings on in the way we do. — Isaac

Agreed. No biological reason, yet we do it anyway. So we have physics that doesn’t answer, we have metaphysics that does answer but doesn’t satisfy.

What an odd bunch of creatures we are, huh? -

Joshs

6.7kThe 'bizarre claim' I was actually referring to was the one implied by an 'investigation' into they way things seem to us without (bracketing out) the question of reality (external states). I just don't believe one approaches the question of how some thing seems to one with a blank slate. I think given almost any question at all one will have preconceptions about it. — Isaac

Joshs

6.7kThe 'bizarre claim' I was actually referring to was the one implied by an 'investigation' into they way things seem to us without (bracketing out) the question of reality (external states). I just don't believe one approaches the question of how some thing seems to one with a blank slate. I think given almost any question at all one will have preconceptions about it. — Isaac

Husserl’s epoche, otherwise known as the phenomenological reduction or ‘bracketing’ of presuppositions, gets a lot of flack. But the general

principe here is one that is widely applied both in philosophy and in the sciences. Notions of folk psychology, naive perception, the relation between the personal and the sub-personal or your distinction between experience and mental events all involve a ‘bracketing’ of appearance and pre-supposition i. favor of a more fundamental truth. As a realist, you believe in the independent existence of a world outside of our interaction with it. For you this is an indubitable , or founding presupposition, and it is what orients the bracketing by science of naive appearance and preconception.

For Husserl the existence of the world as an independent fact is not a founding presupposition but a preconception which can be bracketed. When one does this one has the opportunity to reveal a more fundamental grounding for science and philosophy in the irreducible interaction between subjective and objective poles of experience. Thus, no independent subject and no independent world.

Just the structural a priori that makes preconception possible. -

hypericin

2.1kI'm claiming that the evidence we have thus far points to such a lack of neural criteria for the collection of the various activities at 1 into the grouping of 2 that we must have learned those groups. — Isaac

hypericin

2.1kI'm claiming that the evidence we have thus far points to such a lack of neural criteria for the collection of the various activities at 1 into the grouping of 2 that we must have learned those groups. — Isaac

You keep referring to this trove of evidence without citing it. Your account raises far more questions than it answers.

* How do you account for novel sensations? If you smell something new, it smells like something. How can this be, if we haven't learned how to group it?

* We have immense neural machinery to process sensory data. Did all this come after language use? Then why do other animals have it too?

* Every animal recoils from pain, and manifestly finds it unpleasant. Only humans have to be taught this?

* Animals and babies are deemed to be unaware? In spite of having the behaviors we correlate with awareness?

* How would we learn anything, starting from a point of undifferentiated neural activity? Both auditory words and what they are pointing to would be mere neural noise.

It is far more reasonable to believe that sensations are abstractions of specific neural activities, and that this abstraction is built in.

No reason to have the collection 'smelling coffee' at all, other than for communication. — Isaac

My dog strongly disagrees. Scents carry information on where food is, what is safe to eat and what is not. The purpose of being aware of your environment is not to just communicate, it is to be able to act on it, in a manner more sophisticated than reflexive instinct.

Moreover, even if your account were accurate, which I don't agree with at all, there is still something sensations are like, for us adults. Socially constructed, or no. You can argue that it is an illusion, that is, it is not what it seems, but not that it doesn't exist. I argue that they exist with the same strength of "I think therefore I am". For this something to be communicable, you need to demonstrate how to differentiate between cases where smells are swapped, colors are inverted, etc, and where they are not. -

Luke

2.7kThat argument is circular. If you decide that some collection of neural activity is called 'smelling coffee' then obviously 'smelling coffee' is going to then be common to all, you defined it that way. — Isaac

Luke

2.7kThat argument is circular. If you decide that some collection of neural activity is called 'smelling coffee' then obviously 'smelling coffee' is going to then be common to all, you defined it that way. — Isaac

I never said it was some collection of neural activity.. I can only imagine that the findings that there isn’t a one-to-one correspondence comes from testing subjects’ neural activity while they are smelling coffee (or while they are “in the presence of coffee” as you originally put it). Therefore, what is in common to them all is that they are smelling coffee. They all need to be smelling coffee in order to find that there is no common neural activity while doing so, I take it. -

hypericin

2.1kThe contention that the aroma of coffee cannot be described in words is blatantly wrong. — Banno

hypericin

2.1kThe contention that the aroma of coffee cannot be described in words is blatantly wrong. — Banno

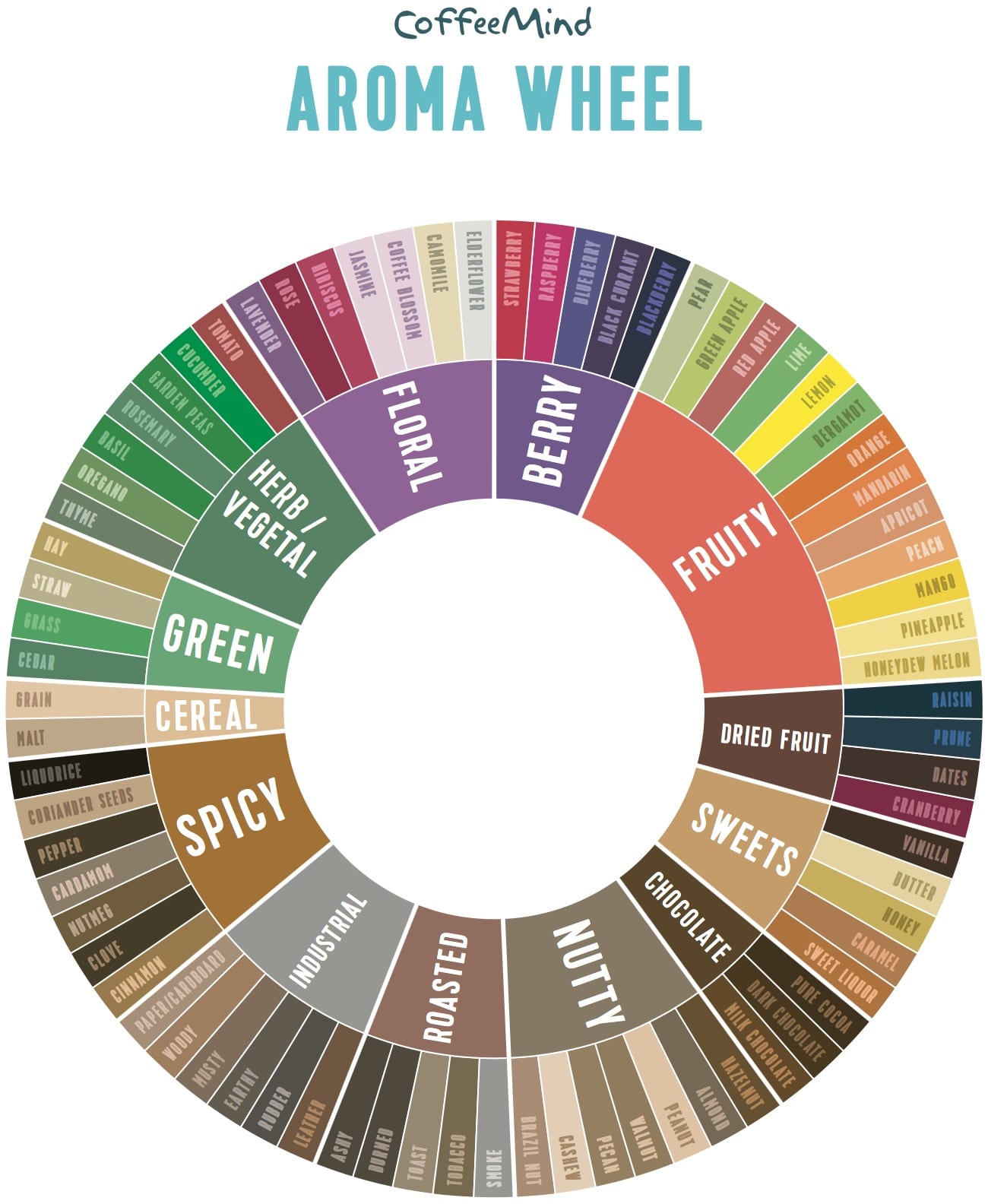

Coffee is a complex and varied aroma, and can have overtones of other aromas depending on the variety. At the center of the wheel should be the smell of coffee itself. Show me someone who can look at that and know what coffee smells like, without having smelled it before.

If the scent of coffee is describable why is this impossible:

.There is a state of affairs where A's (smell-of-coffee) is the same as B's. There is a state of affairs where A's (smell-of-coffee) is same as B's (smell-of-feces), and vice versa. There exists no verbal exchange between A and B which can tell them which state of affairs holds. because 2 is inexpressible. — hypericin -

Banno

30.6kAt the center of the wheel should be the smell of coffee itself. — hypericin

Banno

30.6kAt the center of the wheel should be the smell of coffee itself. — hypericin

What's that, then? What exactly is "the smell of coffee itself"? @Isaac - here's the essentialism mentioned earlier - as if there were one essential aroma of coffee. The transcendental argument implicit in hypericin's view seems to be that we use the word coffee, therefore there must be some one thing to which the word "coffee" refers - the essential smell of coffee. There has to be a something in the middle of the wheel.

But there isn't.

Instead, the aroma of coffee is a family resemblance, a way in which we talk about a group of things that have nothing specifically in common.

Notice the grammatical resemblance between "the smell of coffee itself" and the nonsense phrase "the thing-in-itself"? Here's that mad view that we can never see things as they are in themselves, but only as they appear to us. Stove's Gem, again. -

Banno

30.6kAnd again, here's the reason this thread can go on indefinitely. Each time an ineffable is mooted, some fool thereby tries to tell us what it is. And as I said in the OP,

Banno

30.6kAnd again, here's the reason this thread can go on indefinitely. Each time an ineffable is mooted, some fool thereby tries to tell us what it is. And as I said in the OP,

The problem with claiming that something is ineffable is, of course, the liar-paradox-like consequence that one has thereby said something about it. — Banno

Enough rope. -

hypericin

2.1k

hypericin

2.1k

The use of "the smell of coffee" is no different than the use of the smell of any of the other overtones in your wheel. There are phenolic compounds common to roasted coffee we identify as coffee smelling. Coffee just confuses the issue because it is very complex. What about "the smell of ammonia?"

Instead, the aroma of coffee is a family resemblance, a way in which we talk about a group of things that have nothing specifically in common. — Banno

Nothing specifically in common? Not much of a "family resemblance".

Here's that mad view that we can never see things as they are in themselves, — Banno

Who's claiming we can see things as they are in themselves. Talk about nonsense phrase.

Instead of going off about the red herring stoves gem some more why don't you answer:If the scent of coffee is describable why is this impossible:

.There is a state of affairs where A's (smell-of-coffee) is the same as B's. There is a state of affairs where A's (smell-of-coffee) is same as B's (smell-of-feces), and vice versa. There exists no verbal exchange between A and B which can tell them which state of affairs holds. because 2 is inexpressible.

— hypericin — hypericin -

Banno

30.6k...

Banno

30.6k...

@Isaac, you might be interested in my comments here and here, which address why I think this characterisation of science misguided.

As a realist, you believe in the independent existence of a world outside of our interaction with it. For you this is an indubitable , or founding presupposition, and it is what orients the bracketing by science of naive appearance and preconception. — Joshs

Realism is just supposing that statements are either true or false, that this is the correct grammar to adopt in taking about how things are, that the appropriate logic is bivalent. Talk of "the independent existence of a world outside of our interaction with it" is irrelevant, misleading philosophical twaddle. -

hypericin

2.1kAnd as I said in the OP,

hypericin

2.1kAnd as I said in the OP,

The problem with claiming that something is ineffable is, of course, the liar-paradox-like consequence that one has thereby said something about it. — Banno

If that's good enough for you why bother with a thread in the first place? "Yggzavil is effable. Hey, I mentioned it, after all. "

You can mention anything. The point is that you can't describe anything. -

Banno

30.6kNothing specifically in common? Not much of a "family resemblance". — hypericin

Banno

30.6kNothing specifically in common? Not much of a "family resemblance". — hypericin

That sentence seem to imply that you have not quite understood what a family resemblance is.

It is here that Wittgenstein’s rejection of general explanations, and definitions based on sufficient and necessary conditions, is best pronounced. Instead of these symptoms of the philosopher’s “craving for generality,” he points to ‘family resemblance’ as the more suitable analogy for the means of connecting particular uses of the same word. There is no reason to look, as we have done traditionally—and dogmatically—for one, essential core in which the meaning of a word is located and which is, therefore, common to all uses of that word. We should, instead, travel with the word’s uses through “a complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing” (PI 66). Family resemblance also serves to exhibit the lack of boundaries and the distance from exactness that characterize different uses of the same concept. Such boundaries and exactness are the definitive traits of form—be it Platonic form, Aristotelian form, or the general form of a proposition adumbrated in the Tractatus. It is from such forms that applications of concepts can be deduced, but this is precisely what Wittgenstein now eschews in favour of appeal to similarity of a kind with family resemblance. — SEP

Notice the rejection of forms that goes along with this anti-essentialism. The concepts we use are constructed by us for our purposes, not found floating in some ideal void. They need have no centre. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThat's your claim. It's not what I've said. — Isaac

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThat's your claim. It's not what I've said. — Isaac

What you said is that there is a lack of one-to-one correspondence, and then you described this as a gap. I can remove "gap" if you want, and say that the lack of corresponds presents a "difference". This implies that the two are not the same.

It's not missing. The difference is that one's a name and the other is a

So epiphenomenalism then? Just because a correspondence has yet to be empirically demonstrated does not mean there isn’t one.

— Mww

collection of neurons firing. — Isaac

So, the difference implies that the named thing is not the same thing as the described thing.

You've misunderstood reference. 'The apple' refers to the apple. They're two different things (one an expression, the other a fruit). They don't both 'refer' to different things. 'The apple' refers. The apple is just an apple. — Isaac

You have this wrong. It is not me misunderstanding, I fully understand, that you are producing a bad misrepresentation. This is not analogous to "apple" and "fruit", where "fruit" refers to the type of thing which the apple is. "Neurons firing" refers to a completely different type of thing than the named thing, "smell", and cannot be said to be a type of smell.

If your proposal is that the named thing is "neurons firing", and a special type of neurons firing constitutes a smell, then we might have something to work on. But the proposal that "smell" is the named thing, rather than the descriptive term, and "neurons firing" is the descriptive phrase rather than a named thing, is simply nonsensical, and cannot take us anywhere.

Of course it does. Your spleen is in the group {parts of MU}. — Isaac

You've changed the name from "MU" to "parts of MU". Of course the name "parts of MU" name the parts, that is explicit. But the name "MU" does not name any of the parts, which was your claim that it names the parts.

That group was christened by naming something MU which was not a simple. You christened that group by naming the entity MU even though you do not know it's actual constituents. The point of all this being that you don't need to know what makes up the sensation 'smelling coffee' in order to name it. — Isaac

No Isaac, that's still nonsensical, logic does not work that way. Naming a thing such as "MU" does not imply that you've "christened" a group named "the parts of MU". That's a basic category mistake. You ought to distinguish between naming an individual thing, and naming a group, collection, set, or type, of thing. If the thing named is supposed to be a group, then this must be made explicit in the naming, as you do with "the parts of...". But if you just name a thing "MU", you are naming one individual, not a collection of things.

ndeed, but denying a one-to-one correspondence is not, I think, the same as denying a correspondence of any sort.

What I'm saying is that we group some loose collection of neural activity as 'smelling coffee' so whenever any activity which falls into that group occurs we're inclined to think that we're smelling coffee. — Isaac

Isaac, in order to say that a specific collection of neural activity corresponds with smelling coffee, this must be a one-to-one correspondence. Otherwise that activity could sometimes signify something else, or smelling coffee could occur without any of that neural activity. It makes no sense at all to say that this neural activity corresponds with smelling coffee, but it's not a one-to-one correspondence. If it sometimes corresponds, and sometimes does not, then we cannot make the general conclusion that this neural activity corresponds with smelling coffee.

The contention that the aroma of coffee cannot be described in words is blatantly wrong. — Banno

Yeah, judging by your wheel of aroma, it can be described in pretty much whatever words anyone wants to use. And something that can be described in whatever words anyone wants, is pretty much the same thing as something that can't be described with words at all. -

Banno

30.6kWhat you said is that there is a lack of one-to-one correspondence, and then you described this as a gap. I can remove "gap" if you want, and say that the lack of corresponds presents a "difference". This implies that the two are not the same. — Metaphysician Undercover

Banno

30.6kWhat you said is that there is a lack of one-to-one correspondence, and then you described this as a gap. I can remove "gap" if you want, and say that the lack of corresponds presents a "difference". This implies that the two are not the same. — Metaphysician Undercover

On your argument, the copy of Joyce's Ulysses sitting next to me on the bookcase is two different things, a novel and a block of cellulose.

Yeah, judging by your wheel of aroma, it can be described in pretty much whatever words anyone wants to use. — Metaphysician Undercover

Of course it can be described with any word one wants to use, and provided this functions as part of the task at hand, that's fine. That's how words work. -

Isaac

10.3kit seems like there must be some method by which a sip of this liquid gives the experience with this name, and no other, — Mww

Isaac

10.3kit seems like there must be some method by which a sip of this liquid gives the experience with this name, and no other, — Mww

Why do think that? Have the same drinks not given you different experiences at different times? Did wine taste the same to you at five as it does at 50? Does water give you the same experience when thirsty as it does when added in excess to your whisky?

For Husserl the existence of the world as an independent fact is not a founding presupposition but a preconception which can be bracketed. When one does this one has the opportunity to reveal... — Joshs

This is the issue. One cannot 'reveal' something one did not previously think without the concept of one's thoughts having previously been wrong on some matter. If it is possible to be wrong on some matter, there must exist some external state against which one is comparing one's thought to determine it's wrong.

It's not about 'external worlds', it's about external states - information, not matter. It's merely a description of a system. Any defined system must have internal states and states external to it (otherwise it's not defined as we can say nothing about it - it's just 'everything'). Any complex networked system must also have boundary states (otherwise it would either be a single node or linearly connected). This means that internal states have to infer the condition of external states from the condition of boundary states. We've just described a system. There's no need for any commitment to realism, all this could be taking place in a computer or a field of pure information. It's just derived necessarily from the description of a system.

Phenomenology appears to me to be saying that the internal states can infer the condition of other internal states. They could, but there'd be no reason to change any first inference. There's no 'revelation' no 'investigation'. You might one day feel one way, another day, feel another. There's no reason to prefer one over another. One is not 'investigating' anything, one is merely changing one's mind arbitrarily.

If you smell something new, it smells like something. — hypericin

Just restating the claim doesn't make it true. This is the central claim that I'm denying. Smells don't 'smell like something'. There's no other thing. There's the smell, there's your response to it. Nothing else in between - no 'experience of coffee' in addition to the coffee and your response to it. We've looked really quite hard and failed to find any such thing. I don't know what more evidence you want.

We have immense neural machinery to process sensory data. Did all this come after language use? Then why do other animals have it too? — hypericin

No. Why would it?

Every animal recoils from pain, and manifestly finds it unpleasant. Only humans have to be taught this? — hypericin

No. Firstly, we don't recoil from pain. There's zero evidence we recoil from pain and in fact, I can pretty much trace the signal from nociceptor to muscle and prove to you that we don't recoil from pain. We recoil from stimulated nociceptors. We decide afterwards that what just happened was 'pain'

In fact we don't even need a cortex at all to recoil from nociceptors, we can recoil from nociceptors and have not the slightest idea that anything has just happened at all. You're better off trying to make 'essence of coffee' a thing than you are 'essence of pain'. 'Pain' is definitely not a thing. There's no doubt about this at all. People's reports of being in 'pain' involve interactions between at least eight different major brain regions, three of which aren't even cortical, and there's no consistent pattern of involvement in any combination of these regions, fro example the anterior insula can even create 'pain' in the absence of any nociceptive stimuli, the valence of pain has even been experimentally shown to be modulated by areas as obscure as the face-recognition areas of the fusiform face area via the amygdala. There's absolutely no one-to-one correspondence between the 'experience of pain' and any neural goings on. We infer that we're 'in pain' from a whole ton of unrelated interocepted signals, and most of that inference is culturally modulated.

Animals and babies are deemed to be unaware? In spite of having the behaviors we correlate with awareness? — hypericin

There is a difference between being 'aware' and being 'aware of..'

It is far more reasonable to believe that sensations are abstractions of specific neural activities, and that this abstraction is built in. — hypericin

It's nothing to do with 'reasonable', it's to do with ignorance. It was 'reasonable' to believe the sun went round the earth... until we found out it didn't.

My dog strongly disagrees. Scents carry information on where food is, what is safe to eat and what is not. The purpose of being aware of your environment is not to just communicate, it is to be able to act on it, in a manner more sophisticated than reflexive instinct. — hypericin

And what need is there for any groupings in this description of behaviour?

I can only imagine that the findings that there isn’t a one-to-one correspondence comes from testing subjects’ neural activity while they are smelling coffee (or while they are “in the presence of coffee” as you originally put it). Therefore, what is in common to them all is that they are smelling coffee. — Luke

Nope. Thinking of coffee does it too. Smelling something you think is going to be coffee but isn't, expecting coffee...

Isaac, you might be interested in my comments here and here, which address why I think this characterisation of science misguided. — Banno

By coincidence, I've just replied to @Joshs in almost exactly those terms... I put it in terms of information systems theory - no need even for a material world to exist, it would be the case inside a computer too. Any defined system has to have states which are external to it and to resist entropic decay, it has to infer those states to act in a distribution gradient against them. Internal states merely investigating other internal states makes no sense at all.

It seems to me little more than laziness. Science gets complicated so people recoil and think they can 'investigate' stuff they're less likely to be wrong about. But I'm increasingly uncharitable at my age...

What you said is that there is a lack of one-to-one correspondence, and then you described this as a gap. — Metaphysician Undercover

Nope. Read again.

in order to say that a specific collection of neural activity corresponds with smelling coffee, this must be a one-to-one correspondence. Otherwise that activity could sometimes signify something else, or smelling coffee could occur without any of that neural activity. — Metaphysician Undercover

Indeed. It does exactly that. -

Luke

2.7kI can only imagine that the findings that there isn’t a one-to-one correspondence comes from testing subjects’ neural activity while they are smelling coffee (or while they are “in the presence of coffee” as you originally put it). Therefore, what is in common to them all is that they are smelling coffee.

Luke

2.7kI can only imagine that the findings that there isn’t a one-to-one correspondence comes from testing subjects’ neural activity while they are smelling coffee (or while they are “in the presence of coffee” as you originally put it). Therefore, what is in common to them all is that they are smelling coffee.

— Luke

Nope. Thinking of coffee does it too. — Isaac

Does what too? -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kOn your argument, the copy of Joyce's Ulysses sitting next to me on the bookcase is two different things, a novel and a block of cellulose. — Banno

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kOn your argument, the copy of Joyce's Ulysses sitting next to me on the bookcase is two different things, a novel and a block of cellulose. — Banno

You're not quite right there Banno, because "novel" and "block of cellulose" are both descriptive expressions, and neither names a particular thing like "the copy of Joyce's Ulysses sitting next to me on the bookcase" does. The latter is the name you have given to the item, indicated by the definite article "the". The other two are descriptive terms used to describe the item, that is evident from your use of the indefinite article "a" rather than the definite article "the".

Therefore in your usage neither "a novel" nor "a block of cellulose" name a thing, as indicated by the indefinite article. So your statement that these are "two different things" is fundamentally ungrammatical, and simply employed as a trick of sophistry for the sake of a failing argument. Those are just two different descriptive expressions which could be used to describe one and the same thing, the named article. Neither "a novel" nor "a block of cellulose" name a thing, and you practise deception by suggesting that "two different things" are named here.

Of course it can be described with any word one wants to use, and provided this functions as part of the task at hand, that's fine. That's how words work. — Banno

The point though, is that anything which can be described with any word that one wants, (i.e. there is no degree of correctness or wrongness to the description, and absolute arbitrariness is allowed for), will actually not be described at all, when that arbitrarily chosen word is applied. This is because the consequence of designating the thing as describable by any word, is to designate that there is no correct description. And this designation is not itself a description, it is a statement about the thing which does not describe it. In "talking about" a thing, we can go beyond description to say something about the thing which is not descriptive. That allows us to say, about the thing, that it cannot be described, without self-contradiction.

This is part of the reason why "the ineffable" is so difficult, and appears as sort of a paradox. "Description" is a limited expression, it implies a certain type, or way of saying something about something. "Description" is bounded to allow that we can say more about a thing than the concept of "description" allows. This implies that "description" is a part of a larger category "talking about".

Then we have "naming" of the thing, which is categorically different from describing it because it is meant to identify without saying anything about the thing. That's why naming can be absolutely arbitrary, it does not necessarily say anything about the article. So as a basic philosophical principle, "naming" does not say anything "about" the the thing, it is categorically distinct from "talking about". We can apply a name without saying anything about the named thing.

However, we can twist and distort the concept of "naming" to fit it into the category of "talking about". We can say that naming is to say something about the thing, to say that it is the thing which bears this name. (The problem though, and keep this in mind, is that this is deception, because simply naming a thing does not actually show which thing bears that name.) Now we have created a form of "talking about" a thing which is distinct from describing, yet in the same category (through the means of that deception). The categorical separation between "talking about" and "naming" has been annihilated.

So we use "the ineffable" to name (notice the definite article) the thing which we cannot talk about. And if we maintain the categorical separation between "naming" and "talking about", there is no problem with the concept of a named thing which cannot be talked about. But when we make "naming" a form of "talking about", then even to name a thing as the ineffable is contradictory, creating the appearance of some sort of paradox. But this is really just the result of that faulty procedure which describes "naming" as a type of "talking about".

ndeed. It does exactly that. — Isaac

So, before you explicitly said there is no one-to-one correspondence, now you explicitly say there is one-to-one correspondence? What are you really saying? -

Mww

5.4kit seems like there must be some method by which a sip of this liquid gives the experience with this name, and no other,

Mww

5.4kit seems like there must be some method by which a sip of this liquid gives the experience with this name, and no other,

— Mww

Why do think that? Have the same drinks not given you different experiences at different times? — Isaac

How could it, if I call it the same drink? And conversely, if I have different experiences, how could I say such experiences are of the same drink?

————

Did wine taste the same to you at five as it does at 50? Does water give you the same experience when thirsty as it does when added in excess to your whisky? — Isaac

No, but there is a significant categorical distinction herein. These are aesthetic judgements on an object already perceived, not the sensation itself given from objects themselves as they are perceived. They belong to me as a perceiving subject, not to the perceived object. How the taste of wine manifests in me as a sensation is not the same as the sensation that wine manifests from its being a thing. It’s the difference between the kinds of taste there may be, which I decide, rather than the taste there is, which the kind of wine decides.

Of course, the kind of taste I decide I can talk about; the taste the kind of wine decides, I cannot. By the same token, then, the sensation of the satisfaction water gives belongs to me, but that sensation by which water satisfies, belongs to it. Pretty easy to see why coffee lacks the sensation of curing my thirst, but satisfies the same basic criteria as the experience of water. -

Joshs

6.7kOne cannot 'reveal' something one did not previously think without the concept of one's thoughts having previously been wrong on some matter. If it is possible to be wrong on some matter, there must exist some external state against which one is comparing one's thought to determine it's wrong.

Joshs

6.7kOne cannot 'reveal' something one did not previously think without the concept of one's thoughts having previously been wrong on some matter. If it is possible to be wrong on some matter, there must exist some external state against which one is comparing one's thought to determine it's wrong.

It's not about 'external worlds', it's about external states - information, not matter. It's merely a description of a system. Any defined system must have internal states and states external to it (otherwise it's not defined as we can say nothing about it - it's just 'everything'). Any complex networked system must also have boundary states (otherwise it would either be a single node or linearly connected). This means that internal states have to infer the condition of external states from the condition of boundary states. We've just described a system. There's no need for any commitment to realism, all this could be taking place in a computer or a field of pure information. It's just derived necessarily from the description of a system.

Phenomenology appears to me to be saying that the internal states can infer the condition of other internal states. They could, but there'd be no reason to change any first inference. There's no 'revelation' no 'investigation'. You might one day feel one way, another day, feel another. There's no reason to prefer one over another. One is not 'investigating' anything, one is merely changing one's mind arbitrarily. — Isaac

Phenomenology begins by bracketing notions like ‘state’ and patterns of ‘information’, which are not as much of an improvement over the concept of matter as many think. The problem is that they put identity before difference and try to derive differences from the relations is among identities. The assumption of identity is the idea that there exist states whose identity persists over time (even if only temporarily).

“no need even for a material world to exist, it would be the case inside a computer too.” No need for a material world in order to have a real world. Realism depends not of physicalism or materialism, but on this assumption of at least temporarily persisting self -identity. The real is that which endures as itself. Thus there are all kinds of real objects, including patterns of informationn.

Phenomenology shows how the ‘illusion’ of self-identity is constituted out of the flow of appearances of changing sense, how systems, states, real pattens of ‘information’ and correlations are constituted, founding our mathematics, formal logics and sciences. -

Joshs

6.7kRealism is just supposing that statements are either true or false, that this is the correct grammar to adopt in taking about how things are, that the appropriate logic is bivalent. Talk of "the independent existence of a world outside of our interaction with it" is irrelevant, misleading philosophical twaddle. — Banno

Joshs

6.7kRealism is just supposing that statements are either true or false, that this is the correct grammar to adopt in taking about how things are, that the appropriate logic is bivalent. Talk of "the independent existence of a world outside of our interaction with it" is irrelevant, misleading philosophical twaddle. — Banno

Supposing that statements are either true or false , a logic of bivalence, leads us down the rabbit hole of the meaning or role of ‘truth’ and ‘falsity’, which has been investigated in recent threads here. Davidson and Putnam thought that truth was a concept worth keeping, despite Putnam’s conceptual relativism . Not coincidentallly, both of them rejected value-relativism. I don’t think you’ll find among those philosophers ( Rorty, Rouse, Heidegger, etc) who are both conceptual and ethical relativists, any enthusiasm for the usefulness of propositional truth.

So I think one can justifiably argue that a belief in a world that is independent of our concepts or ethical values is a a necessary pre-condition for supporting the usefulness of bivalent logic. -

Isaac

10.3kDoes what too? — Luke

Isaac

10.3kDoes what too? — Luke

Triggers one of a number of neural networks associated with reports of 'smelling coffee'.

I'm baffled as to why this is causing such confusion.

Several different neural events result in us reporting we experience 'smelling coffee'

There's no single thing connecting all the different events other than that they all happen to result (sometimes) in reports of 'smelling coffee'

Since there's no biological link, and no external world link, the only conclusion we can reach is that it's our own post hoc construction to conceptualise any given neural event as 'smelling coffee'.

before you explicitly said there is no one-to-one correspondence, now you explicitly say there is one-to-one correspondence? What are you really saying? — Metaphysician Undercover

Read more carefully. I can't comment of stuff I haven't said.

How could it, if I call it the same drink? And conversely, if I have different experiences, how could I say such experiences are of the same drink? — Mww

I meant the same as in 'wine', or 'beer', or (on topic) 'coffee'. To claim there's such an entity as 'the smell of coffee' requires that coffee produce a consistent experience, but it doesn't seem to.

These are aesthetic judgements on an object already perceived, not the sensation itself given from objects themselves as they are perceived. — Mww

Where is that sensation? What are we using as evidence (rational or empirical) that such a thing exists? It's certainly not identifiable in the brain. I don't find it through interception. I don't even find myself to have an intuition that it exists. It doesn't seem to need to exist rationally. Is it just a gut feeling?

Phenomenology shows... — Joshs

How can phenomenology 'show' anything? The term denotes the revealing of what's 'really' there, but if there's not right or wrong it cannot show. It can only invent, same as everything else. No better, no worse.

You can't have it both ways. You can't claim there's no 'way things are' and then say "the way things are is that there's no way things are".

If your claim is that phenomenology correctly shows us how things are, then there must be some way things actually are, some true propositions opposing false ones. -

Banno

30.6kSo you are now saying that since George Eliot was also named Mary Ann Evans, these are two distinct individuals, and that the author of Middlemarch and Mary Ann Evans are different people.

Banno

30.6kSo you are now saying that since George Eliot was also named Mary Ann Evans, these are two distinct individuals, and that the author of Middlemarch and Mary Ann Evans are different people.

Go back to the original point:

We can have two different descriptions of the very same thing. We can have two names for the very same thing. We can have a description and a name that both refer to one thing.Seems to me that we can have two descriptions, one listing the chemical and physiological reactions of my brain in the presence of coffee, and another saying that I smell coffee, and that these are two different ways of saying much the same thing. Isaac? — Banno

The point though, is that anything which can be described with any word that one wants, (i.e. there is no degree of correctness or wrongness to the description, and absolute arbitrariness is allowed for), will actually not be described at all — Metaphysician Undercover

You failed to note "provided this functions as part of the task at hand". Look to the use. The meaning of a sentence is found in its use. -

Banno

30.6kHow could it, if I call it the same drink? And conversely, if I have different experiences, how could I say such experiences are of the same drink? — Mww

Banno

30.6kHow could it, if I call it the same drink? And conversely, if I have different experiences, how could I say such experiences are of the same drink? — Mww

Why not? We use the word "red" for sunsets and sports cars and blood, but these things are not the same colour. Perhaps all they have in common is that we sometimes use the word "red" to describe them. Different blends of coffee taste different; different baristas will produce different tasting brews from the very same beans and machine.

Here again is the fallacious essentialism, the transcendental argument:

- We use the same word for several things

- The only way we could use the same word for several things is if those things have something in common

- Therefore the things have something on common.

-

Joshs

6.7kIf your claim is that phenomenology correctly shows us how things are, then there must be some way things actually are, some true propositions opposing false ones. — Isaac

Joshs

6.7kIf your claim is that phenomenology correctly shows us how things are, then there must be some way things actually are, some true propositions opposing false ones. — Isaac

There are so many wonderful ways in which humans beings can talk about what matters to us , what is relevant and how it is relevant. For instance , harmonious, integral, intimate, consistent, similar, compatible, intelligible. Of all of these, ‘true and false’ are

particularly narrow and impoverished.

“It is no more than a moral prejudice that the truth is worth more than appearance; in fact, it is the world's most poorly proven assumption. Let us admit this much: that life could not exist except on the basis of perspectival valuations and appearances; and if, with the virtuous enthusiasm and inanity of many philosophers, someone wanted to completely abolish the “world of appearances,” – well, assuming you could do that, – at least there would not be any of your “truth” left either! Actually, why do we even assume that “true” and “false” are intrinsically opposed? Isn't it enough to assume that there are levels of appearance and, as it were, lighter and darker shades and tones of appearance – different valeurs, to use the language of painters? Why shouldn't the world that is relevant to us – be a fiction? And if someone asks: “But doesn't fiction belong with an author?” – couldn't we shoot back: “Why? Doesn't this ‘belonging' belong, perhaps, to fiction as well? Aren't we allowed to be a bit ironic with the subject, as we are with the predicate and object? Shouldn't philosophers rise above the belief in grammar? With all due respect to governesses, isn't it about time philosophy renounced governess-beliefs?” – The world with which we are concerned is false, i.e., is not fact but fable and approximation on the basis of a meager sum of observations; it is "in flux," as something in a state of becoming, as a falsehood always changing but never getting near the truth: for--there is no "truth" ('Nietzsche, Will to Power.)

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum