-

T Clark

16.1kThis discussion is about human mental processes, the mind. I’ve made a lot of statements about mental phenomena here on the forum, mostly based on if-I -remember-correctly and seems-to-me evidence. In this post, I’m setting out to put a bit of meat on that skeleton.

T Clark

16.1kThis discussion is about human mental processes, the mind. I’ve made a lot of statements about mental phenomena here on the forum, mostly based on if-I -remember-correctly and seems-to-me evidence. In this post, I’m setting out to put a bit of meat on that skeleton.

The mind is the set of faculties responsible for mental phenomena. Often the term is also identified with the phenomena themselves. These faculties include thought, imagination, memory, will, and sensation. They are responsible for various mental phenomena, like perception, pain experience, belief, desire, intention, and emotion. — Wikipedia

So, mental processes, mental faculties, mental phenomena - emotion, thought, memory, perception, learning, imagination, instinct, attention, pain, motivation, language, action, decision making, maintaining bodily processes. I’m sure there are others worth mentioning. One mental process I intentionally left off the list is experience/consciousness. I don’t want this to be a discussion about consciousness, by which I mean I specifically want it not to be a discussion about consciousness. There have been dozens, probably hundreds of those discussions on the forum and few went anywhere useful. Beyond that, I don’t think we can have a useful discussion of consciousness until we have some kind of understanding of non-conscious mental processes.

I want to talk about the mind by looking at several specific processes - thought, language, instinct, maintenance of bodily homeostasis - through the lenses of psychology, linguistics, and cognitive science. I picked these particular focuses because they interest me and I had interesting sources of information, including the following:

- “The Language Instinct” by Stephen Pinker

- “What is an Instinct” by William James

- “The Descent of Man” by Charles Darwin

- “The Feeling of What Happens” by Antonio Damasio.

I don’t necessarily endorse the specific information and interpretations presented in these sources, but I think they provide examples of useful ways to look at the mind. How to think about thinking. We can discuss the specifics of the summaries I provide. It would be great to look at other mental processes too. I would like to look at specific scientific sources for the ideas we discuss. On the other hand, for me, introspection is indispensable. To the extent possible I would like to avoid arm waving - unsupported overgeneralization. And, as I mentioned, no discussion of consciousness, self-awareness, or whether I experience green the same way other people do.

That’s enough for the OP. I’ll start with specific information in my next post. -

T Clark

16.1kI’m going to run through my sources in no particular order. I don’t intend to show a comprehensive view of human cognition, or even necessarily a consistent one. As I noted, I just want to get a feel for how mental processes in general might look and work and good ways to talk about them.

T Clark

16.1kI’m going to run through my sources in no particular order. I don’t intend to show a comprehensive view of human cognition, or even necessarily a consistent one. As I noted, I just want to get a feel for how mental processes in general might look and work and good ways to talk about them.

“The Language Instinct” by Stephen Pinker.

Stephen Pinker is a professor of cognitive science and psycholinguistics at MIT. This book provides a very detailed presentation of his understanding of how human language works and how it develops in children, making specific reference to scientific evidence including studies of the effects of brain damage caused by trauma, disease, or birth defects; the results of PET, MRI, and other imaging on living brains; language learning in healthy children starting at infancy; language performance by adults and children; genetic studies of families with a history of language disorders; studies of twins separated at birth; comparative studies of world languages; and others. According to Pinker, the findings presented in the book apply to all human languages studied.

Pinker’s conclusions I think are relevant to this discussion include the following:

Language is instinctive. He quotes Darwin as saying that language is “an instinctive tendency to acquire an art.”

Language does not control thought, it’s the other way around. The book includes a section debunking the Whorf hypothesis, which claims that different languages promote and restrict the kinds of ideas that people can develop and understand.

Human grammar is an example of a “discrete combinatorial system.” A finite number of discrete elements (in this case, words) are sampled, combined, and permuted to create larger structures (in this case, sentences) with properties that are quite distinct from those of their elements. He quotes William Von Humboldt saying language “makes infinite use of finite media.” By this he means that words, phrases, and sentences are made up of elements that can be combined and recombined in an infinite number of ways, always constrained from above by the innate structure of human grammar. Words are built up of elements called “morphemes.” Although the morphemes themselves are memorized and vary depending on language, they are combined following rigid rules which are not. The same type of unlearned rules apply to how phrases are constructed from words and sentences from phrases.

Although brain functions, including language, are distributed throughout the brain, there are areas in the brain, Pinker calls them “organs,” which clearly have grammatical functions. Damage to those brain areas can lead to very specific types of grammatical problems. Also, although he recognizes that specific traits are not generally controlled by single genes, studies show that changes in specific genes or lack of those genes can result in language dysfunction that can be passed down from parent to child.

Perhaps most interesting and important, from my point of view, is that people do not think in English, Mandarin, or Swahili. They think in what he calls “mentalese.” Babies and people who have grown up with no language clearly think. He hypothesizes that mentalese is universal and innate in humans.

“The Descent of Man” by Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin was a naturalist, biologist, and geologist, born in 1809 and died in 1882. In his discussion of language as instinct, Pinker quotes Darwin as writing:

Human language is an instinctive tendency to acquire an art. It certainly is not a true instinct, for every language has to be learned. It differs, however, widely from all ordinary arts, for man has an instinctive tendency to speak, as we see in the babble of our young children; while no child has an instinctive tendency to brew, bake, or write.

“What is an Instinct” by William James

William James was a psychologist and pragmatist philosopher, born in 1842 and died in 1910. James writes “Instinct is usually defined as the faculty of acting in such a way as to produce certain ends, without foresight of the ends, and without previous education in the performance.”

In “The Language Instinct”, Pinker discusses James’ position:

A language instinct may seem jarring to those who think of language as the zenith of the human intellect and who think of instincts as brute impulses that compel furry or feathered zombies to build a dam or up and fly south. But one of Darwin’s followers, William James, noted that an instinct possessor need not act as a “fatal automaton.” He argued that we have all the instincts that animals do, and many more besides; our flexible intelligence comes from the interplay of many instincts competing. Indeed, the instinctive nature of human thought is just what makes it so hard for us to see that it is an instinct.

He then quotes James as writing:

It takes…a mind debauched by learning to carry the process of taking the natural seem strange, so far as to ask for the why of any instinctive human act. To the metaphysician alone can such questions occur as: Why do we smile, when pleased, and not scowl? Why are we unable to talk to a crowd as we talk to a single friend? Why does a particular maiden turn our wits so upside-down? The common man can only say, “Of course we smile, of course our heart palpitates at the sight of the crowd, of course we love the maiden, that beautiful soul clad in that perfect form, so palpably and flagrantly made from all eternity to be loved!” And so probably does each animal feel about the particular things it tends to do in presence of particular objects. They, too, are a priori syntheses…

James also writes:

Nothing is commoner than the remark that Man differs from lower creatures by the almost total absence of instincts, and the assumption of their work in him by “reason.”...[But] the facts of the case are really tolerably plain! Man has a far greater variety of impulses than any lower animal; and any one of these impulses, taken in itself, is as “blind” as the lowest instinct can be; but, owing to man’s memory, power of reflection, and power of inference, they come each one to be felt by him, after he has once yielded to them and experienced their results, in connection with a foresight of those results…

…It is plain then that, no matter how well endowed an animal may originally be in the way of instincts, his resultant actions will be much modified if the instincts combine with experience, if in addition to impulses he have memories, associations, inferences, and expectations, on any considerable scale…

…there is no material antagonism between instinct and reason…

“The Feeling of What Happens” by Antonio Damasio.

Antonio Damasio is a neuroscientist as USC best known for his books on the neural basis of consciousness. This book in particular is mostly about consciousness, but in the early part he talks about non-conscious precursors to self-awareness that are appropriate for this discussion. Damasio identifies what he calls a “proto-self” made up of non-conscious neurological and endocrine bodily functions that connect the brain and peripheral body and which allow maintenance of equilibrium in mechanical, biological, and chemical bodily systems, called “homeostasis.” As Damasio writes:

I have come to conclude that the organism, as represented inside its own brain, is a likely biological forerunner for what eventually becomes the elusive sense of self. The deep roots for the self, including the elaborate self which encompasses identity and personhood, are to be found in the ensemble of brain devices which continuously and nonconsciously maintain the body state within the narrow range and relative stability required for survival. These devices continually represent, nonconsciously, the state of the living body, along its many dimensions. I call the state of activity within the ensemble of such devices the proto-self, the nonconscious forerunner for the levels of self which appear in our minds as the conscious protagonists of consciousness: core self and autobiographical self…

…[The proto-self is] a collection of brain devices whose main job is the automated management of the organism's life. As we shall discuss, the management of life is achieved by a variety of innately set regulatory actions—secretion of chemical substances such as hormones as well as actual movements in viscera and in limbs. The deployment of these actions depends on the information provided by nearby neural maps which signal, moment by moment, the state of the entire organism. Most importantly, neither the life-regulating devices nor their body maps are the generators of consciousness.

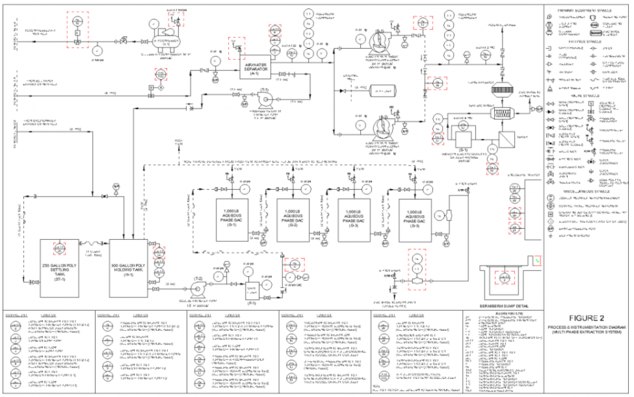

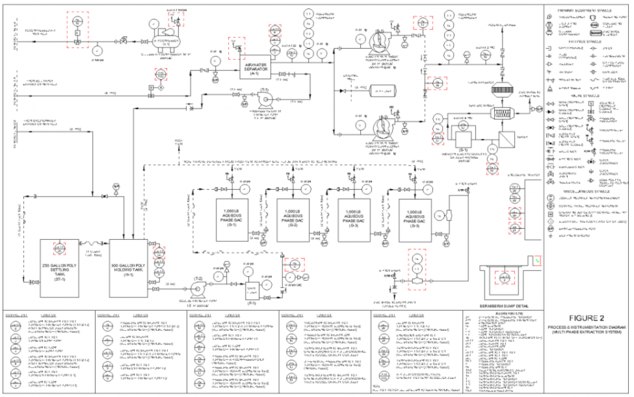

Damasio’s description of the proto-self brings to mind the design of mechanical and chemical process engineering systems, which I have some familiarity with, although I am not a chemical, process, or mechanical engineer. The drawing below is a piping and instrumentation diagram from a groundwater treatment system which includes removal of floating petroleum.

This is not a system that I worked on myself and I recognize it is hard to read. On the drawing, pipes are shown as solid lines with arrows; pumps, heaters, compressors, and other devices are shown as icons; vessels and tanks are shown as rectangles, and valves are shown as bowtie shapes. Instruments including heat, pressure, fluid level, pH, flow rate, and other sensors are shown as circles connected to the system by signal lines shown a dashed lines with arrows. Not shown on the drawing is a programmable control box, a computer, which takes input from the instruments and, based on that input turns pumps and other equipment on or off; opens and closes valves, records operating data, and sets off alarms with the purpose maintaining system status within established operating parameters. I think this is a good analogy for the proto-self system Damasio describes.

Boy, this has gotten a lot longer than I intended. I’ve tried to cut back, but there are important things I didn’t want to leave out. I had intended to include a discussion of the following books:

- “How Emotions are Made” by Lisa Feldman Barrett

- “The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind” by Julian Jaynes

- “Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking” by Douglas Hofstadter and Emmanual Sander.

But I decided not to. Maybe I’ll bring them up later in the discussion.

So, down to work. I have presented some ideas about how the mind works from scientists I consider credible whose ideas make sense to me. I’d like to discuss what the proper approach to thinking about the mind is. I consider these good examples. My conclusion - the mind is not magical or even especially mysterious, although there is a lot we don’t know. Mostly it’s just a foundation of business-as-usual biology resulting in the very powerful and complex thinking, feeling, seeing, remembering, speaking faculties of the human beings we all are.

And please - no discussion of consciousness experience or awareness. -

javi2541997

7.2k

javi2541997

7.2k

“The Language Instinct” by Stephen Pinker. — T Clark

It is a very substantive and drafted OP. I have been thinking and I guess the following paper can be attached to your arguments about the complexity of thinking. Language is one of the main examples indeed.

Probably you already know it but there is a book called How to do Things with Words by John Langshaw Austin. Well, he also wrote a philosophical paper called Sense and Sensibilia.

According to his thoughts in those papers he wrote:

Austin argues that [Ayer] fails to understand the proper function of such words as "illusion", "delusion", "hallucination", "looks", "appears" and "seems", and uses them instead in a "special way...invented by philosophers." According to Austin, normally these words allow us to express reservations about our commitment to the truth of what we are saying, and that the introduction of sense-data adds nothing to our understanding of or ability to talk about what we see.

Again, Austin argues in Other Minds:

He [Austin] claims, is that if I say that I know X and later find out that X is false, I did not know it. Austin believes that this is not consistent with the way we actually use language. He claims that if I was in a position where I would normally say that I know X, if X should turn out to be false, I would be speechless rather than self-corrective. He gives an argument that this is so by suggesting that believing is to knowing as intending is to promising— knowing and promising are the speech-act versions of believing and intending respectively.

I wish these brief quotes can be useful and interesting for you. Glad to see an OP from you again. -

T Clark

16.1kThe mind may impact 'bodily processes' but, it does not maintain them. A number of the other items you list are also not of the mind. Of being the key word. — ArielAssante

T Clark

16.1kThe mind may impact 'bodily processes' but, it does not maintain them. A number of the other items you list are also not of the mind. Of being the key word. — ArielAssante

Seems to me that would only be true if the term "mental processes" only applies to conscious phenomena and intentional acts and decisions. That's a pretty circular argument. It's not as if Damasio's proto-self is sitting off by itself doing it's thing. It is fully integrated into our nervous system and, as I noted, it acts as the substrate for other mental phenomena, some of which are conscious.

This proto-mind acts. It makes our bodies do things using our brain, nerves, and muscles. How is that different from me flexing my arm, except in that it is non-conscious.

A number of the other items you list are also not of the mind. Of being the key word. — ArielAssante

I don't know what you mean by this. -

T Clark

16.1kIt is a very substantive and drafted OP. — javi2541997

T Clark

16.1kIt is a very substantive and drafted OP. — javi2541997

Thanks, Javi. I appreciate that.

Probably you already know it but there is a book called How to do Things with Words by John Langshaw Austin. Well, he also wrote a philosophical paper called Sense and Sensibilia. — javi2541997

I had never heard of Austin or his book. I looked him up on the web and looked at the book on Amazon. Sounds like it has been very influential. I have very little experience with the philosophy of language. I read a little Wittgenstein 50 years ago. That's about it. That's part of the reason I wanted to put this thread together. I wanted to have a foundation of knowledge about how the mind works so I could have something useful to say about language and the mind.

He [Austin] claims, is that if I say that I know X and later find out that X is false, I did not know it. Austin believes that this is not consistent with the way we actually use language. He claims that if I was in a position where I would normally say that I know X, if X should turn out to be false, I would be speechless rather than self-corrective. He gives an argument that this is so by suggesting that believing is to knowing as intending is to promising— knowing and promising are the speech-act versions of believing and intending respectively. — javi2541997

I'm not sure how to use this in the context of Pinker's work and that of other scientists who study language, how it fits in to what they have learned. That's often an issue with science and philosophy in general. Certainly the philosophy has to be consistent with the science. Maybe it's that what Austin says has to do with meaning rather than structure, function, and performance, which is mostly what Pinker is talking about. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

, in The Physics of Consciousness thread*1 is also pursuing a physical explanation for how the mind works, without assuming any non-physical contributions. His theory is based on a technical concept of "Cohesion", which could be imagined as a novel physical force, but that I interpret in terms of "Holism" or "Systems Theory". However, both of those alternative approaches to Reductionism are more rational than empirical, hence more philosophical than scientific.So, down to work. I have presented some ideas about how the mind works from scientists I consider credible whose ideas make sense to me. I’d like to discuss what the proper approach to thinking about the mind is. I consider these good examples. My conclusion - the mind is not magical or even especially mysterious, although there is a lot we don’t know. Mostly it’s just a foundation of business-as-usual biology resulting in the very powerful and complex thinking, feeling, seeing, remembering, speaking faculties of the human beings we all are.

And please - no discussion of consciousness experience or awareness. — T Clark

Anyway, it seems that excluding the non-physical aspect of mental processes runs into a blank wall on the Quantum level. There, "business-as-usual-biology" becomes logically fuzzy, mathematically uncertain, and physically unpredictable, as we approach the foundations of reality. Ironically, there is no there there.

So, the only way I see to find our way through the sub-atomic fog is to make use of a semi-physical tool : Information --- found in nature in three forms : energy, matter, mind. I agree that the mental functions of the brain are "not magical". But they are Meaningful ; which is inherently a "conscious experience or awareness". :nerd:

*1. The Physics of Consciousness

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/724342 -

T Clark

16.1kYears ago bought Damasio’s first book. What is memorable is: it was one of two books out of hundreds I tossed in the garbage. I considered it kindergarten level and a waste of my time and money. — ArielAssante

T Clark

16.1kYears ago bought Damasio’s first book. What is memorable is: it was one of two books out of hundreds I tossed in the garbage. I considered it kindergarten level and a waste of my time and money. — ArielAssante

Ok.

Do you realize the model you have apparently accepted is only theory? — ArielAssante

Agreed. I tried to be clear in the OP. The authors seem credible, their ideas seem plausible and supported, but I'm not committed to any of the positions I described. Everything I wrote about is "only theory." -

T Clark

16.1k↪Enrique , in The Physics of Consciousness thread*1 is also pursuing a physical explanation for how the mind works, without assuming any non-physical contributions. His theory is based on a technical concept of "Cohesion", which could be imagined as a novel physical force, but that I interpret in terms of "Holism" or "Systems Theory". However, both of those alternative approaches to Reductionism are more rational than empirical, hence more philosophical than scientific. — Gnomon

T Clark

16.1k↪Enrique , in The Physics of Consciousness thread*1 is also pursuing a physical explanation for how the mind works, without assuming any non-physical contributions. His theory is based on a technical concept of "Cohesion", which could be imagined as a novel physical force, but that I interpret in terms of "Holism" or "Systems Theory". However, both of those alternative approaches to Reductionism are more rational than empirical, hence more philosophical than scientific. — Gnomon

As I've noted many times, Enrique's posts on scientific subjects are pseudo-science - incomprehensible mashups of buzzwords and jargon that don't really mean anything.

I don't see the ideas I've described as reductionist at all. If they seem that way, it's probably because I cut off chunks to highlight the aspects I find particularly interesting.

Anyway, it seems that excluding the non-physical aspect of mental processes runs into a blank wall on the Quantum level. There, "business-as-usual-biology" becomes logically fuzzy, mathematically uncertain, and physically unpredictable, as we approach the foundations of reality. Ironically, there is no there there. — Gnomon

Generally, quantum effects are found at the level of atoms, i.e. about 10 picometers or 1/10,000 of a micrometer, while biological processes are found at the level of cells, i.e. about one micrometer. As far as I know, there is no evidence to show or reason to believe that quantum effects affect mental phenomena directly. Just because quantum particles and mental processes are in some sense mysterious to some people, that doesn't mean there is any connection.

This thread is about scientific approaches to mental processes. If you have actual scientific evidence to describe or clarify your ideas about non-physical aspects, reductionist or holistic, please provide it. I don't necessarily criticize your ideas about non-physical processes, but this is probably not the right thread to discuss them. -

Enrique

845As I've noted many times, Enrique's posts on scientific subjects are pseudo-science - incomprehensible mashups of buzzwords and jargon that don't really mean anything. — T Clark

Enrique

845As I've noted many times, Enrique's posts on scientific subjects are pseudo-science - incomprehensible mashups of buzzwords and jargon that don't really mean anything. — T Clark

If you don't bother to think about a model of the chemistry and anatomy of neuroscience until you comprehend it, what YOU'RE doing is pseudoscience. I talk about the properties of ion channels, electric currents in aqueous solution, EM fields and radiation in a way that is based on scientific papers. If you need a diagram that hasn't been drawn yet I can understand, the concepts are very visual. I gather you want to think about mind at a higher level of emergence than biochemistry and cellular anatomy. Sometimes it makes sense to deconstruct scientific models into more manageable fragments of the total picture, and I can try to accomplish that if it becomes relevant to your discussion.

Anyways, enough of defending myself from baseless attacks lol I'll try to make a pertinent contribution: can you describe in more detail what exactly Pinker means by "mentalese"? This seems key to his concept of the thought/language interface. -

apokrisis

7.8kI want to talk about the mind by looking at several specific processes - thought, language, instinct, maintenance of bodily homeostasis - through the lenses of psychology, linguistics, and cognitive science. — T Clark

apokrisis

7.8kI want to talk about the mind by looking at several specific processes - thought, language, instinct, maintenance of bodily homeostasis - through the lenses of psychology, linguistics, and cognitive science. — T Clark

A way to sharpen your approach would be to look at the issue through the eyes of function rather than merely just process.

You have started at the reductionist end of the spectrum by conceiving of the mind as a collection of faculties. If you can break the mind into a collection of component processes, then of course you will be able to see how they then all "hang together" in a ... Swiss army knife fashion.

And as kids, didn't we all covet a Swiss army knife with the most tools - including the spike for getting stones out of horses hooves - only to find they are useless crap in reality. :grin:

Instead, think about the question in terms of the holism of a function. Why does the body need a nervous system all all? What purpose or goal does it fulfil? What was evolution selecting for that it might build such a metabolically expensive network of tissue?

Can you name this essential function yet? Can you then see how it is implemented in neurobiology?

Your process approach will lead towards the Swiss army knife brand of cogsci - the brain as a set of modules or cognitive organs.

A functional approach leads instead to "whole brain" theories, like the Bayesian Brain, where the neurobiology is described in holistic architecture terms. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

By "reductionism", I'm referring to the method of Atomism : dissect the material word far enough down to its foundations, and you will find atoms of Mind. Scientists have been using such methods for centuries, but still have not found the the basic building block of Mind (ideas ; knowledge ; awareness). Yet, they are still looking for the elusive "ghost in the machine". At least, Enrique is looking for a whole system (Cohesion ; Integration), not a sub-Planck-scale bit of matter (Atom). :smile:I don't see the ideas I've described as reductionist at all. If they seem that way, it's probably because I cut off chunks to highlight the aspects I find particularly interesting. — T Clark

Atoms of Mind: The "Ghost in the Machine" Materializes

https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-94-007-1097-9

Is quantum physics behind your brain's ability to think? :

From consciousness to long-term memories, the human brain has some peculiar computing abilities – and they could be explained by quantum fuzziness

https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg22830500-300-is-quantum-physics-behind-your-brains-ability-to-think/

-

apokrisis

7.8kAs I've noted many times, Enrique's posts on scientific subjects are pseudo-science - incomprehensible mashups of buzzwords and jargon that don't really mean anything. — T Clark

apokrisis

7.8kAs I've noted many times, Enrique's posts on scientific subjects are pseudo-science - incomprehensible mashups of buzzwords and jargon that don't really mean anything. — T Clark

This is accurate.

As far as I know, there is no evidence to show or reason to believe that quantum effects affect mental phenomena directly. Just because quantum particles and mental processes are in some sense mysterious to some people, that doesn't mean there is any connection. — T Clark

In fact living organisms arise at the point in nature where molecular machinery can be used to harness quantum effects. So life may not be quantum in @Enrique's emergent sense, but it is quantum in that it employs its classical structure to exploit the energetic possibilities of the "quantum realm".

An example is the respiratory chain that powers every cell. Basically it is a ladder of quantum tunnelling formed by a series of sulphur-iron clusters embedded at precisely spaced distances in a protein matrix. A "hot" electron enters the chain at one end and safely milked of its energy in about 15 steps before finally being whisked away by an oxygen atom acceptor.

So a nonlocal quantum effect jumps the electron down the waiting pathway. But the classical physics is what forms the pathway. And the information about the design of the pathway is ultimately contained in the genes.

Thus the biology isn't "made of quantumness". It is instead the opposite thing of (semiotic) information ulitimately using its control over classical molecular structure to exploit the quantum realm for energetic advantage.

The same is true of other ubiquitous biological components. Enzymes rely on quantum level control of chemical reactions. So the brain is "quantum" just because it is made of cells that have to do energetic things.

And brains are also quantum because the same biology is used in in sensory transduction – how the receptors that interface between the nervous system and the world can actually physically "handle" the information coming at them in the form of electromagnetic, chemical, or mechanical energy.

So quantum biology is now a thing. But it means the opposite of saying that life and mind arise from the quantum. Instead life and mind arise from being able to use classical machinery to harness useful quantum effects ... with an overarching functional purpose in mind. -

Enrique

845

Enrique

845

You guys are hopeless lol Matter resides on a spectrum from relatively coherent to decoherent states, of which standard issue superposition, entanglement, chemical bonding and classical dynamics are all instances, listed from most to least coherent. Electric currents are relatively coherent electromagnetic states. Electric currents are modulated in neurons by fluctuations in ion concentration. Signal transmission within neurons is a phenomenon of coherence current operative upon the medium of electrons or more accurately quantum orbital energy density contours, a sort of perturbation in what can be described as an electromagnetic sea. This model explains all we have discovered about neuron anatomy. But you're certainly welcome to disagree based on the facts, and I'll probably be able to convince you of the contrary.

That's so compact as to almost be incomprehensible, so if you want the details, read the OP posts of my The Physics of Consciousness thread. Then we'll have some actual biochemistry and cellular anatomy to talk about instead of the usual epithets. -

T Clark

16.1k@Enrique, @apokrisis, @Gnomon

T Clark

16.1k@Enrique, @apokrisis, @Gnomon

I made a mistake. I stuck my nose into the quantum effects on thinking trap when I didn't have to. I should have kept my mouth shut. That's not what this thread is about. It's about scientifically supported ways of thinking about mental processes not including consciousness.

I hope it's not too late to stop this wagon rolling down the hill. I have nobody to blame but myself. -

T Clark

16.1kcan you describe in more detail what exactly Pinker means by "mentalese"? This seems key to his concept of the thought/language interface. — Enrique

T Clark

16.1kcan you describe in more detail what exactly Pinker means by "mentalese"? This seems key to his concept of the thought/language interface. — Enrique

Pinker writes:

The idea that thought is the same thing as language is an example of what can be called a conventional absurdity: a statement that goes against all common sense but that everyone believes because they dimly recall having heard it somewhere and because it is so pregnant with implications.

Here are his arguments:

- We know many animals without language who clearly think. Most obvious example, young children. Studies have shown that even infants can recognize concepts of number, time, and space. They can even make simple moral judgements. Also, there are deaf people who were never taught any language. If they are taught after a certain age, they will never have a sound language foundation. Even so, they clearly think, communicate in simple ways, plan, make decisions, and act. He also discusses chimpanzees who clearly can think at some level without language.

- There are people who have lost their language or had it disrupted by trauma or disease who remain as intelligent and aware as they were before the disruption happened. They can still often communicate with gestures or by drawing pictures.

- Pinker spends quite a bit of time debunking the Whorf hypothesis, the idea that language controls the kinds of thoughts people can have. No, Eskimos do not have 100 names for snow. Yes, Apaches are able to express ideas about time. So can Mandarin speakers, even though their language doesn't include any tenses. Pinker writes "there is no scientific evidence that languages dramatically shape their thinkers ways of thinking."

- It is common people have a hard time putting their thoughts into words. Sometimes they can't think of the word they are looking for. How can anyone say "oh, no, that's not what I meant to say" if your words are the same as your thoughts.

- Many people claim that they do not think in words but rather in geometric, auditory, or sensory images. That is certainly true of me sometimes. Even more often I seem to do my thinking without any awareness at all. After pouring information into my head, if I go do something else for a while, I find that my mind has organized and analyzed the data so that when I sit down to write, the words just come out without reflection.

-

apokrisis

7.8kI made a mistake. — T Clark

apokrisis

7.8kI made a mistake. — T Clark

:razz:

Well at least you can add the general constraint of ruling out all discussions of mind that makes appeals to the notion of it as some kind of fundamental substance. That would rule out the usual suspects.

You are appealing to a metaphysics of localised process. I am saying go one step further and employ a metaphysics of global function.

But you could rule that out too and only allow the metaphysics you have chosen in advance, I guess. -

T Clark

16.1kScientists have been using such methods for centuries, but still have not found the the basic building block of Mind (ideas ; knowledge ; awareness). — Gnomon

T Clark

16.1kScientists have been using such methods for centuries, but still have not found the the basic building block of Mind (ideas ; knowledge ; awareness). — Gnomon

But this is exactly what the people I have referenced are doing successfully. They are using standard scientific methods to study the "basic building block of Mind." @apokrisis has suggested looking at mind from point of view of function rather than of process. I think that's similar to what you are proposing - a more holistic understanding. I'm still working on my response to him. -

Tom Storm

10.9kI don't have time to explore this in any depth and forgive my awkward phrasing - but a continuing question I have (which may be of relevance to mental processes) is the idea that the world has no intrinsic properties and that humans see reality in terms of neutrally generated matrix of gestalts. These generate what we know as reality. An example would be an understanding that space and time are a product of generalized neurocognitive system that allows us to understand the world. Or perhaps 'a' world - the one we have access too.

Tom Storm

10.9kI don't have time to explore this in any depth and forgive my awkward phrasing - but a continuing question I have (which may be of relevance to mental processes) is the idea that the world has no intrinsic properties and that humans see reality in terms of neutrally generated matrix of gestalts. These generate what we know as reality. An example would be an understanding that space and time are a product of generalized neurocognitive system that allows us to understand the world. Or perhaps 'a' world - the one we have access too.

Maybe this is too Kantian and feel free piss it off if you find it superfluous. My understanding of Kant in the Critique is that he viewed space as a preconscious organizing feature of the human mind - a critic, (I forget who) compared this to a kind of scaffolding upon which we're able to understand the physical world. I suspect @joshs would say that we don't understand it as such; we construct the semblance of an intelligible world based on shared values. Or something similar. -

apokrisis

7.8kI'm still working on my response to him. — T Clark

apokrisis

7.8kI'm still working on my response to him. — T Clark

While you are at it, I would add that the scientifically grounded approach would be being able to say why some "this" is a more specified version of "that" more general kind of thing. So if the mind is the specific example in question, to what more fundamental generality are you expecting to assimilate it to.

So if you are saying the mind is some kind of assembly of component processes, then what is the most general theory of such a "thingness". I would say rather clearly, it is a machine. You are appealing to engineering.

Likewise others are trying to argue that mind is a particularised example of the more general thing that is a substance.

And I am arguing that mind is a particularised example of the more general thing that is an organism. Or indeed, if we keep digging down, of a dissipative structure. And ultimately, a semiotic relation.

So clarity about ontology is critical to seeing you have chosen an approach, and yet other approaches exist.

Cutting to the chase, we both perhaps agree that the mind isn't simply some variety of substance – even an exotic quantum substance or informational substance. But then do you think biology and neurobiology are literally machinery? Aren't they really organismic in the knowing, striving, intentional and functional sense?

In simple language, an organism exists as a functioning model of its reality. And it all depends on the mechanism of a semiotic code.

The genes encode the model of the body. The neurons encode the model of the body's world. Then words encode the social model of the individual mind. And finally numbers have come to encode the world of the human-engineered machine.

So it is the same functional trick repeated at ever higher levels of organismic organisation and abstraction.

Organismic selfhood arises to the degree there is a model that is functionally organising the world in play.

So - contra Pinker - language may not create "thought", but it does transform it quite radically. It allows the animal mind to become structured by sociocultural habit. Humans are "self consciously aware" as social programming exists to make us include a model of the self as part of the world we are functionally engaged with. A higher level viewpoint is created where we can see ourselves as social actors. Animals just act, their selfhood being an implicit, rather than explicit, aspect of their world model.

Anyway, the point is that we want to know what is the "right stuff" for constructing minds. It ain't exotic substances. It ain't mechanical engineering. But what holds for all levels of life and mind is semiosis - the encoding of self~world models that sustain the existence of organismic organisation. -

Agent Smith

9.5kFrom what I gather, the model of the mind as offered for critique and/or endorsement seems (too) machine-like for my taste. True that our brain probably is the mind and neuroscience has proven to some extent that our brains are basically (bio)electrochemical devices; nonetheless, the model is, in my humble opinion, too simplistic. Of course I could be seeing/imagining things - the alleged complexity of the mind being merely an illusion, one of many ways ignorance manifests itself.

Agent Smith

9.5kFrom what I gather, the model of the mind as offered for critique and/or endorsement seems (too) machine-like for my taste. True that our brain probably is the mind and neuroscience has proven to some extent that our brains are basically (bio)electrochemical devices; nonetheless, the model is, in my humble opinion, too simplistic. Of course I could be seeing/imagining things - the alleged complexity of the mind being merely an illusion, one of many ways ignorance manifests itself.

My two cents...for what it's worth. -

apokrisis

7.8ka continuing question I have (which may be of relevance to mental processes) is the idea that the world has no intrinsic properties and that humans see reality in terms of neutrally generate matrix of gestalts. — Tom Storm

apokrisis

7.8ka continuing question I have (which may be of relevance to mental processes) is the idea that the world has no intrinsic properties and that humans see reality in terms of neutrally generate matrix of gestalts. — Tom Storm

Thank goodness cogsci eventually took its enactive or ecological turn about 20 years back. This is what semioticians were referring to as the construction of an Umwelt - the mental model that is of a self in its world. And yes, gestalt psychology was also saying the same before the computationalists crashed the party and made a noisy mess.

But such modelling is the opposite of neutral. It is supremely self-interested in that the construction of an organismic selfhood is what anchors the whole exercise. -

Philosophim

3.5kSo, down to work. I have presented some ideas about how the mind works from scientists I consider credible whose ideas make sense to me. I’d like to discuss what the proper approach to thinking about the mind is. I consider these good examples. My conclusion - the mind is not magical or even especially mysterious, although there is a lot we don’t know. Mostly it’s just a foundation of business-as-usual biology resulting in the very powerful and complex thinking, feeling, seeing, remembering, speaking faculties of the human beings we all are. — T Clark

Philosophim

3.5kSo, down to work. I have presented some ideas about how the mind works from scientists I consider credible whose ideas make sense to me. I’d like to discuss what the proper approach to thinking about the mind is. I consider these good examples. My conclusion - the mind is not magical or even especially mysterious, although there is a lot we don’t know. Mostly it’s just a foundation of business-as-usual biology resulting in the very powerful and complex thinking, feeling, seeing, remembering, speaking faculties of the human beings we all are. — T Clark

Sounds good to me T-Clark. You've cited the correct people for this conclusion. While this is a nice summation of several different findings, do you have anything of your own to add? Should we change how we approach life? Does this affect morality? Or is it simply a nice result you wanted to share with us all from what appears to be a lot of research on your part? -

BC

14.2kHighly substantive OP and followup comments.

BC

14.2kHighly substantive OP and followup comments.

maintaining bodily processes — T Clark

Some brain scientist (if only I remembered correctly) noted that the primary function/purpose of the brain is "maintaining bodily processes" which needs to be understood broadly. Small clusters of cells in the brain stem are responsible for such essentials as heart beat, respiration, and waking up from sleep. But most of the brain considerable resources are applied in making sure the body gets fed, watered, sheltered, mated, and so on. We have seen what happens to people whose brains don't tend to business. (They tend to do poorly and die early -- unless another brain looks after them.)

Our quotidian lives require the full-bore efforts of our advanced brains. Art? Literature? Darwin's books? Google? Mars rovers? Nobel prizes? Yeah yeah yeah, very impressive. All of us keeping society up and running day after day, decade after decade, is a mammoth operation overseen by ordinary but expert brains that won't get a cash prize and a medal.

My brain loves to use the resources left over after feeding and shelter are taken care of to think about existenz quite apart from everything else. Is recreational thinking a 'need'? Maybe. Certainly it's a 'want'. One of the horrors of the quotidian work-a-day world is reaching the end of the day again and again without having had a moment to just think, let alone have creative thought and dialogue with other brains.

So... award your brain a Nobel prize for seeing you through to an old age where you have time to speculate, write, think.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum