-

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe field of study usually called "ethics" is traditionally divided into three sub-fields:

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe field of study usually called "ethics" is traditionally divided into three sub-fields:

- The core of them, often just called "ethics" itself but called "normative ethics" when needed to distinguish it from the other two fields, is the traditional philosophical study of ethics, giving general all-encompassing models of what kinds of commands, intentions, actions, or states of affairs are good, or moral, or just, and when and why they are.

- Another subfield, called "applied ethics", is about applying various of those normative ethical models to specific real-world circumstances, seeking answers to questions about what particular thing is best in some particular circumstances, according to those more general models.

- The third subfield, called "meta-ethics", is the newest and most abstract of them, concerning itself originally with the meaning of moral sentences, a topic now called moral semantics; as the field of meta-ethics has now expanded to encompass other topics besides that, such as what kinds of things in the world (if any) constitute the reality (if any) of moral facts, the topic called moral ontology; and how we can know the answers to any of the above questions, the topic called moral epistemology.

I am of the peculiar opinion that applied ethics is not properly speaking a branch of philosophy at all, but is rather the seed of an entire field of underdeveloped ethical sciences, parallel to the physical sciences, concerned not with building theories (descriptive models, complex beliefs) to satisfy all of our sensations or observations, but instead strategies (prescriptive models, complex intentions) to satisfy all of our appetites.

Furthermore, I hold that the field of normative ethics is something of a mutt, and as such should be dissolved entirely into the two other sub-fields of ethics, with the part that is dissolved into applied ethics becoming the root of those ethical sciences, and the part that is dissolved into meta-ethics being divided across its various sub-fields.

In this thread I want to talk about the first half of that dissolution of normative ethics, the part that goes into the ethical sciences, which then cease to be philosophy anymore. I'll do a different thread later on dissolving the rest of it into meta-ethics, which would then be the whole of the remainder of ethical philosophy (just as the physical sciences stopped being "natural philosophy", leaving only metaphysics for philosophy).

On the one hand, I think something like a normative ethical model, a general and all-encompassing model of what is good, is what the most general and fundamental of the ethical sciences should aim to build, but based on the a posteriori phenomenal experience of our contingent appetites rather than a priori philosophizing, akin to how fundamental models of physics are built on a posteriori phenomenal experience of our contingent senses.

The experiential part of this would be conducted via something akin to emic ethnography: going through the things that other people go through to confirm or deny first-hand what those experiences are actually like, just like we replicate experiments to confirm or deny claimed observations. The strategic part, like the theoretic part of physical sciences, can thereafter be conducted entirely with mathematical logic and creative thinking, to then be later tested through first-person experience again.

- That most general and fundamental subfield of the ethical sciences, playing the foundational role to them that physics plays to the physical sciences, is what I think deserves to be called "ethics" simpliciter. That field's task would be to catalogue the needs or ends, and the abilities or means, of different moral agents and patients, like how physics catalogues the functions of different particles.

- Building atop that field, the ethical analogue of chemistry would be to catalogue the aggregate effects of many such agents interacting, as much of the field of economics already does, in the same way that chemical processes are the aggregate interactions between many physical particles.

- Atop that, the ethical analogue of biology would be to catalogue the types of organizations of such agents that arise, and the development and interaction of such organizations individually and en masse, like biology catalogues organisms.

- Lastly, atop that, the ethical analogue of psychology would be to catalogue the educational and governmental apparatuses of such organizations, which are like the self-awareness and self-control, the mind and will so to speak, of such organizations.

Like the physical sciences naturally feed into engineering and technology, I propose that these ethical sciences naturally feed into entrepreneurship and business, as all of those endeavors are ultimately about value: things like wealth, power, and freedom all boil down ultimately to the ability to fulfill intentions, desires, or appetites, to avoid pain and suffering and obtain pleasure and flourishing.

I hold that such ethical sciences – contingent, a posteriori applications of the philosophy of morality and justice – are the bridge to ever more useful businesses, in the same way that the physical sciences are the bridge from the philosophy of reality and knowledge – of which they are contingent, a posteriori applications – to ever more useful technologies.

And just as those physical sciences have over time largely supplanted religious authority in the educational social role, so too I hold that these ethical sciences should in time supplant state authority in the governmental social role, as I will elaborate upon in a later thread. -

khaled

3.5k- That most general and fundamental subfield of the ethical sciences, playing the foundational role to them that physics plays to the physical sciences, is what I think deserves to be called "ethics" simpliciter. That field's task would be to catalogue the needs or ends, and the abilities or means, of different moral agents and patients, like how physics catalogues the functions of different particles.

khaled

3.5k- That most general and fundamental subfield of the ethical sciences, playing the foundational role to them that physics plays to the physical sciences, is what I think deserves to be called "ethics" simpliciter. That field's task would be to catalogue the needs or ends, and the abilities or means, of different moral agents and patients, like how physics catalogues the functions of different particles.

- Building atop that field, the ethical analogue of chemistry would be to catalogue the aggregate effects of many such agents interacting, as much of the field of economics already does, in the same way that chemical processes are the aggregate interactions between many physical particles.

- Atop that, the ethical analogue of biology would be to catalogue the types of organizations of such agents that arise, and the development and interaction of such organizations individually and en masse, like biology catalogues organisms.

- Lastly, atop that, the ethical analogue of psychology would be to catalogue the educational and governmental apparatuses of such organizations, which are like the self-awareness and self-control, the mind and will so to speak, of such organizations. — Pfhorrest

I don’t see how any of this tells someone what they should do? It just seems to be cataloguing what people need and want, and the results of that. It reads like the first level is simply psychology, second is economics, third is political science and the last is.... also political science.

I don’t see where ethics comes into the picture. Knowing that people want food, and the consequences of the they all the way to a political level, doesn’t seem to have anything to do with ethics. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhat about descriptive ethics? — Pantagruel

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhat about descriptive ethics? — Pantagruel

That's just a natural or physical (i.e. descriptive) science when you get down to it, a study of what peoples' ethical beliefs are, rather than a study into which ethical beliefs are the correct or incorrect ones.

I don’t see how any of this tells someone what they should do? It just seems to be cataloguing what people need and want, and the results of that. It reads like the first level is simply psychology, second is economics, third is political science and the last is.... also political science.

I don’t see where ethics comes into the picture. Knowing that people want food, and the consequences of the they all the way to a political level, doesn’t seem to have anything to do with ethics. — khaled

All of this is an application of a meta-ethics, an account of what claims about what people should do mean, what would make such claims correct or incorrect, and how to go about figuring out which claims are correct or incorrect. That's sort of the point of the two threads I intended to do here: that normative ethics as normally conceived of is neither here nor there, it's halfway a claim about which things in particular are good or bad, and halfway an account of how to gauge which things are good or bad. I'm saying that it should therefore be dissolved into the other two fields of "ethics" broadly speaking: a philosophical meta-ethics, which gives an account of how to do applied ethical sciences, in the same way that metaphysics (broadly construed as containing epistemology, ontology, etc) is at the end of the day an account of how to do physical sciences: what do our claims about reality mean, what makes them true or false, and how can we tell which is which?

I thought that the whole thing was too long for a single OP, so I divided it up into two, but since this question came up right away, maybe I should just posted the other OP right now, as a response here, and rename the thread...

On the other hand, I think that the actual general approaches to normative ethics that have historically been developed can be better developed and reconciled with each other if they are instead viewed not as competing answers to the same normative ethical question, but as complimentary answers to the different questions within meta-ethics. The primary divide within normative ethics is between consequentialist (or teleological) models, which hold that acts are good or bad only on account of the consequences that they bring about, and deontological models, which hold that acts are good or bad in and of themselves and the consequences of them cannot change that.

The decision between them is precisely the decision as to whether the ends justify the means, with consequentialist models saying yes they do, and deontological theories saying no they don't. I hold that that is a strictly speaking false dilemma, between the two types of normative ethical model, although the strict answer I would give to whether the ends justify the means is "no". But that is because I view the separation of ends and means as itself a false dilemma, in that every means is itself an end, and every end is a means to something more.

This is similar to how my views on ontology and epistemology (see links for previous threads) entail a kind of direct realism in which there is no distinction between representations of reality and reality itself, there is only the incomplete but direct comprehension of small parts of reality that we have, distinguished from the completeness of reality itself that is always at least partially beyond our comprehension. We aren't trying to figure out what is really real from possibly-fallible representations of reality, we're undertaking a fallible process of trying to piece together our direct sensation of small bits of reality and extrapolate the rest of it from them.

Likewise, to behave morally, we aren't just aiming to use possibly-fallible means to indirectly achieve some ends, we're undertaking a process of directly causing ends with each and every behavior, and fallibly attempting to piece all of those together into a greater good.

Perhaps more clearly than that analogy, the dissolution of the dichotomy between ends and means that I mean to articulate here is like how a sound argument cannot merely be a valid argument, and cannot merely have true conclusions, but it must be valid – every step of the argument must be a justified inference from previous ones – and it must have a true conclusion, which requires also that it begin from true premises.

If a valid argument leads to a false conclusion, that tells you that the premises of the argument must have been false, because by definition valid inferences from true premises must lead to true conclusions; that's what makes them valid. If the premises were true and the inferences in the argument still lead to a false conclusion, that tells you that the inferences were not valid. But likewise, if an invalid argument happens to have a true conclusion, that's no credit to the argument; the conclusion is true, sure, but the argument is still a bad one, invalid.

I hold that a similar relationship holds between means and ends: means are like inferences, the steps you take to reach an end, which is like a conclusion. Just means must be "good-preserving" in the same way that valid inferences are truth-preserving: just means exercised out of good prior circumstances definitionally must lead to good consequences; just means must introduce no badness, or as Hippocrates wrote in his famous physicians' oath, they must "first, do no harm".

If something bad happens as a consequence of some means, then that tells you either that something about those means were unjust, or that there was something already bad in the prior circumstances that those means simply have not alleviated (which failure to alleviate does not make them therefore unjust). But likewise, if something good happens as a consequence of unjust means, that's no credit to those means; the consequences are good, sure, but the means are still bad ones, unjust.

Moral action requires using just means to achieve good ends, and if either of those is neglected, morality has been failed; bad consequences of genuinely just actions means some preexisting badness has still yet to be addressed (or else is a sign that the actions were not genuinely just), and good consequences of unjust actions do not thereby justify those actions.

Consequentialist models of normative ethics concern themselves primarily with defining what is a good state of affairs, and then say that bringing about those states of affairs is what defines a good action. Deontological models of normative ethics concern themselves primarily with defining what makes an action itself intrinsically good, or just, regardless of further consequences of the action.

I think that these are both important questions, and they are the moral analogues to questions about ontology and epistemology: fields that I call teleology (from the the Greek telos meaning "end" or "purpose"), which is about the objects (in the sense of "goals" or "aims") of morality, like ontology is about the objects of reality; and deontology (from the Greek deon meaning "duty"), which is about how to pursue morality, like epistemology is about how to pursue reality.

In addition to consequentialist and deontological normative ethical models, there is a third common type, called aretaic or virtue ethics, which holds that morality is about the character, the internal mental states, of the person doing the action, rather than about the action itself or its consequences. I hold that that is also an important question to consider, and that that question is wrapped up with the question of what it means to have free will.

And lastly, though it's not usually studied as a philosophical division of normative ethics, there are plenty of views across history that hold that morality lies in doing what the correct authority commands, whether that be a supernatural authority (as in divine command theory) or a more mundane authority (as in some varieties of legalism). That concern is of course wrapped up in the question of who if anyone is the correct authority and what gives their commands any moral weight, which is the central concern of political philosophy.

So rather than addressing normative ethics as its own field, I prefer approaching those four questions corresponding to four kinds of normative ethical theories as equally important fields:

- teleology (dealing with the objects of morality, the intended ends)

- deontology (dealing with the methods of justice, what the rules should be)

- the philosophy of will (dealing with the subjects of morality, who does the intending), and

- the philosophy of politics (dealing with the institutions of justice, who should enforce the rules).

I would loosely group these together as "meta-ethics" in a slightly different than usual sense, they being the questions necessary to answer in order to pursue the ethical sciences I propose above; in a way analogous to how the fields of...

- ontology (about the objects of reality)

- epistemology (about the methods of knowledge)

- the philosophy of mind (about the subjects of reality), and

- the philosophy of academics (about the institutions of knowledge)

... – which we might likewise group together in a slightly unusual sense as "meta-physics" – address the questions necessary to answer in order to pursue the physical sciences.

In general, I view the correct approach to prescriptive questions about morality and justice to be completely analogous to, but also entirely separate from, the correct approach to descriptive questions about reality and knowledge. This is different from views that hold that one set of questions reduces entirely to the other set of questions, like both scientism (which reduces prescriptive questions to descriptive ones) and constructivism (which reduces descriptive questions to prescriptive ones).

But it is also different from views such as the "non-overlapping magisteria" proposed by Stephen Jay Gould, who held that questions about reality are the domain of science, with its methodologies, while questions about morality were entirely separate in the domain of religion, with its wholly different methodologies.

I hold, like Gould, that they are entirely separate questions, but that perfectly analogous, broadly-speaking scientific, methodologies can be applied to each, and that religious methodologies have historically been (wrongly) applied to both of them as well. This is largely because of my views that prescriptive assertions and opinions are generally analogous in every way to descriptive assertions and opinions, differing only in a quality called "direction of fit".

I'm planning on doing more threads in the near future where I will lay out in more detail my views on those fields of teleology, deontology, will, and politics, that I hold analogous to the fields of ontology, epistemology, mind, and academics. But for now, I will leave off here with a broad overview of the analogous process that I advocate, of which the ethical sciences detailed in the OP are the application:

When it comes to tackling questions about reality, pursuing knowledge, we should not take some census or survey of people's beliefs or perceptions, and either try to figure out how all those could all be held at once without conflict, or else (because that likely will not be possible) just declare that whatever the majority, or some privileged authority, believes or perceives is true.

Instead, we should appeal to everyone's direct sensations or observations, free from any interpretation into perceptions or beliefs yet, and compare and contrast the empirical experiences of different people in different circumstances to come to a common ground on what experiences there are that need satisfying in order for a belief to be true.

Then we should devise models, or theories, that purport to satisfy all those experiences, and test them against further experiences, rejecting those that fail to satisfy any of them, and selecting the simplest, most efficient of those that remain as what we tentatively hold to be true.

This entire process should be carried out in an organized, collaborative, but intrinsically non-authoritarian academic structure.

When it comes to tackling questions about morality, pursuing justice, we should not take some census or survey of people's intentions or desires, and either try to figure out how all those could all be held at once without conflict, or else (because that likely will not be possible) just declare that whatever the majority, or some privileged authority, intends or desires is good.

Instead, we should appeal to everyone's direct appetites, free from any interpretation into desires or intentions yet, and compare and contrast the hedonic experiences of different people in different circumstances to come to a common ground on what experiences there are that need satisfying in order for an intention to be good.

Then we should devise models, or strategies, that purport to satisfy all those experiences, and test them against further experiences, rejecting those that fail to satisfy any of them, and selecting the simplest, most efficient of those that remain as what we tentatively hold to be good.

This entire process should be carried out in an organized, collaborative, but intrinsically non-authoritarian political structure. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhat’s an “appetite” that’s not a desire or intention? What are these “hedonic experiences”? — khaled

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhat’s an “appetite” that’s not a desire or intention? What are these “hedonic experiences”? — khaled

Appetites or hedonic experiences (same thing as I mean them) are things like pain, hunger, thirst, etc. Not a want for a specific state of affairs to be the case, but just a feeling that calls for something or other to be done. What specifically must be done is always underdetermined by appetites, i.e. there are always various possible ways in principle to satisfy an appetite; the same way that what to believe is always underdetermined by observation. It is precisely that underdetermination of a particular state of affairs that makes it always possible to reconcile them: it's just a creative challenge to come up with some state of affairs that satisfies them all, since no particular states of affairs that might irreconcilably conflict are directly demanded by them. -

javi2541997

7.2kAnd just as those physical sciences have over time largely supplanted religious authority in the educational social role, so too I hold that these ethical sciences should in time supplant state authority in the governmental social role, as I will elaborate upon in a later thread. — Pfhorrest

javi2541997

7.2kAnd just as those physical sciences have over time largely supplanted religious authority in the educational social role, so too I hold that these ethical sciences should in time supplant state authority in the governmental social role, as I will elaborate upon in a later thread. — Pfhorrest

I wish we can see it one day. We already did the first step of supplanting science and ethics instead of religion/clergy authority. This is the begging to at least starting to finally coming back to Greek or Roman education system (the best I ever heard of).

To be honest with you I do not believe in the State and the governors but yes somehow we need it because we have the risk of living like a jungle without authority... nevertheless I have a sceptical view on governance because they do whatever to climb in the top of the power instead of point equally principles to all the citizens. I guess it is the truest representation of natural selfishness or competitiveness.

But, implanting a ethics role or principle in our society not only will stop governors but we will finally reach happiness. A rare gift demanded in society. We live in a paradox of modern success where the people know how to get a job because the State says so but they don’t know how to be happy... interesting. -

I like sushi

5.3k“Emic Ethnography” would be better referred to as just ‘ethnography’ as the former is like saying ‘a dark shade of black’. If not some clarification would be useful.

I like sushi

5.3k“Emic Ethnography” would be better referred to as just ‘ethnography’ as the former is like saying ‘a dark shade of black’. If not some clarification would be useful.

Ethnology and ethnography are commonly misapplied. In terms of political sciences there is a large amount of similarity to Berlin’s ‘Monism and Pluralism’ approach - my point being favouring one over the other is to only take in half the picture.

Anthropology straddles numerous subjects. Some aspects of anthropology are more strongly based in empirical measurements than others. ‘Applied Ethics’ is just something akin to what the current guru states as a ‘universal truth’. The solidity of ethics (scientifically speaking) is contained within DNA ... but the species is part of the larger environment (hence the importance of BOTH Monism and Pluralism without being seduced by one over the other.

As creatures - perhaps overly fond - of cutting and categorising; it is a constant habit of ours to reimagine our experience of the world through different lenses. You may as well argue that physics is a type of philosophy because physicists actively use free-formed thinking and imagination to explore and question reality itself and what is commonly perceived as so-called ‘reality’.

On top of the above there is the niggling issue of defining ‘science’. I’m sure you’ve done this elsewhere, but a reminder of your position is probably worth mentioning in the OP. -

Pfhorrest

4.6k“Emic Ethnography” would be better referred to as just ‘ethnography’ as the former is like saying ‘a dark shade of black’. If not some clarification would be useful. — I like sushi

Pfhorrest

4.6k“Emic Ethnography” would be better referred to as just ‘ethnography’ as the former is like saying ‘a dark shade of black’. If not some clarification would be useful. — I like sushi

In an anthropology class I had a long time ago, I was taught that emic ethnography was the newer type, and that etic ethnography had been the usual long before. It might be that all ethnography today is emic, but at least according to that class they're not strictly synonyms.

In any case I kinda didn't even want to use the word "ethnography" there, I just wasn't sure what other noun to attach the adjective "emic" to (the emic vs etic distinction being the main point to make: I'm advocating undergoing the same experiences as others and reporting on those experiences in the first person, rather than just observing or talking to others in the third person), and ethnography seems to be the place it's applied most.

On top of the above there is the niggling issue of defining ‘science’. I’m sure you’ve done this elsewhere, but a reminder of your position is probably worth mentioning in the OP. — I like sushi

I did briefly cover that in the OP, in this paragraph:

ethical sciences – contingent, a posteriori applications of the philosophy of morality and justice – are the bridge to ever more useful businesses, in the same way that the physical sciences are the bridge from the philosophy of reality and knowledge – of which they are contingent, a posteriori applications – to ever more useful technologies. — Pfhorrest

So by science in general I mean an investigation that hinges on appeal to experiences, which is therefore a posteriori, and can shed light on contingent matters. In contrast to a philosophical investigation that is entirely a priori, independent of specific experiences, and so can only reach conclusions about what is necessary or impossible.

The distinction between physical or descriptive sciences (the usual sense of "science" today) and the ethical or prescriptive sciences I'm discussing here is the distinction between empirical experience (or sensations) and hedonic experience (or appetites): an experience that inclines one to think or feel that something is or isn't true or real, vs an experience that inclines one to think or feel that something is or isn't good or moral. -

Pantagruel

3.6kThat's just a natural or physical (i.e. descriptive) science when you get down to it, a study of what peoples' ethical beliefs are, rather than a study into which ethical beliefs are the correct or incorrect ones. — Pfhorrest

Pantagruel

3.6kThat's just a natural or physical (i.e. descriptive) science when you get down to it, a study of what peoples' ethical beliefs are, rather than a study into which ethical beliefs are the correct or incorrect ones. — Pfhorrest

I don't see why that is any reason not to include it.What people do do is certainly relevant in some sense to what they should do. Certainly some people in some circumstances do do what they should do. That would seem to be scientifically significant. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI don't see why that is any reason not to include it. — Pantagruel

Pfhorrest

4.6kI don't see why that is any reason not to include it. — Pantagruel

I'm not excluding it, or saying it shouldn't be done, just that it's not a part of this set of things I'm talking about. -

Pantagruel

3.6kWell, this seems to me impractical and unlikely. These domains barely tolerate restriction by rule of law. What would be the general motivation to adoption?

Pantagruel

3.6kWell, this seems to me impractical and unlikely. These domains barely tolerate restriction by rule of law. What would be the general motivation to adoption? -

180 Proof

16.4k

180 Proof

16.4k

Why "satisfy all of our appetites"? And explain what makes that answer both "ethical" and "scientific". Thanks.I am of the peculiar opinion that applied ethics is not properly speaking a branch of philosophy at all, but is rather the seed of an entire field of underdeveloped ethical sciences, parallel to the physical sciences, concerned not with building theories (descriptive models, complex beliefs) to satisfy all of our sensations or observations, but instead strategies (prescriptive models, complex intentions) to satisfy all of our appetites. — Pfhorrest -

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhy "satisfy all of our appetites"? And explain what makes that answer both "ethical" and "scientific". — 180 Proof

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhy "satisfy all of our appetites"? And explain what makes that answer both "ethical" and "scientific". — 180 Proof

The "what makes it scientific" part I just answered in response to another comment above (TL;DR: by "appetite" I mean a kind of experience, specifically a hedonic one, basically a kind of "pain" etc; and by "science" I mean an investigation that appeals to actual, contingent, a posteriori experiences, whether those are empirical sensations or hedonic appetites):

So by science in general I mean an investigation that hinges on appeal to experiences, which is therefore a posteriori, and can shed light on contingent matters. In contrast to a philosophical investigation that is entirely a priori, independent of specific experiences, and so can only reach conclusions about what is necessary or impossible.

The distinction between physical or descriptive sciences (the usual sense of "science" today) and the ethical or prescriptive sciences I'm discussing here is the distinction between empirical experience (or sensations) and hedonic experience (or appetites): an experience that inclines one to think or feel that something is or isn't true or real, vs an experience that inclines one to think or feel that something is or isn't good or moral. — Pfhorrest

The "what makes it ethical" part is basically asking for a justification for altruistic hedonism as the correct ethics, and that's a long answer that I'm planning to do another thread on later, but the too-short version is: altruism is the ethical face of universalism, the negation relativism; hedonism is the ethical face of phenomenalism, the negation of transcendentalism; transcendentalism requires dogmatism; and both relativism and dogmatism boil down to different forms of simply giving up on even trying to answer the question. -

baker

6k

baker

6k

That description by authority becomes the norm the masses are expected to obey.These domains barely tolerate restriction by rule of law.

What would be the general motivation to adoption? — Pantagruel

It's what we have in psychology, for example: Psychologists study the population, then, based on empirical findings assess what is statistically normal, and then, because the psychologists have considerable institutional power, the statistically normal becomes the norm, the normative that people must live up to or else get stigmatized as "abnormal" and needing treatment. -

180 Proof

16.4k:up: So "ethical science" is like medical science or human ecology (my preferred analogue) or moral psychology ...

180 Proof

16.4k:up: So "ethical science" is like medical science or human ecology (my preferred analogue) or moral psychology ... -

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo "ethical science" is like medical science or human ecology (my preferred analogue) or moral psychology ... — 180 Proof

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo "ethical science" is like medical science or human ecology (my preferred analogue) or moral psychology ... — 180 Proof

I’m not sure that’s accurate, since AFAIK those fields are empirical investigations, that at most describe what people are like and how they react to various things, in the third person. That’s etic when it comes to other people’s hedonic experiences, although of course all empirical science is emic in the sense that it’s grounded in first-person observations.

But if empirical science were done in an analogous etic way, rather than repeating observations to confirm that things really do look like X is true or false to Y type of person in Z context, we would just write down how Y type of person acts (including what they say) regarding the truth or falsify of X in context Z. That isn’t how we actually do empirical science though; we confirm the reported observations for ourselves.

Likewise, the ethical sciences I advocate aren’t just about watching other people and noting whether person type Y acts like (incl. says) X is good or bad in context Z. They’re about actually confirming those reported experiences ourselves: if Alice says that X feels bad in context Z, ethical scientist Bob should put himself in context Z and see if X actually feels bad, and if it doesn’t, get more people to do the same, and control for other factors of the environment and the phenomenon, until they’ve all amassed a large enough assortment of emic, first-person accounts to all agree, from their first-hand experience, on what really does feel good or bad to what type of person in what contexts.

It's basically the same principle that we use to instill morals into children: "how would you like it if that happened to you?" Except even that is more akin to "imagine what it would be like if...", which is once again not science. It's more like making a child go and experience something they made someone else experience so that they know first-hand, don't just imagine, that it's wrong.

People who have not undergone a certain type of experience may not understand why something or another that causes that type of experience, which is unpleasant to certain people, is bad, in the visceral experiential way that we all know that getting punched in the face is bad without needing any kind of fancy moral code to tell us: it just feels bad!

I'm reminded of a news story I read maybe a decade ago about some congress people challenged to live for a relatively short period of time (a month, or maybe a week?) on a median American's budget. They came back reporting about how it was surprisingly hard, they they couldn't figure out ways to simultaneously make all of their ends meet, like they had to decide which foods not to get at the store so they could afford enough of other foods and still pay bills... and all the hundreds of millions of Americans who live like that their entire lives were saying "Duh! This is why we need help! It sucks to live this way! Now you see!?"

To find out what's good or bad, walk some miles in other peoples' shoes, put yourself in their places, experience for yourself what it's like to go through what they go through, and if necessary figure out what's different between you and them that might account for any differences that remain in your experiences.

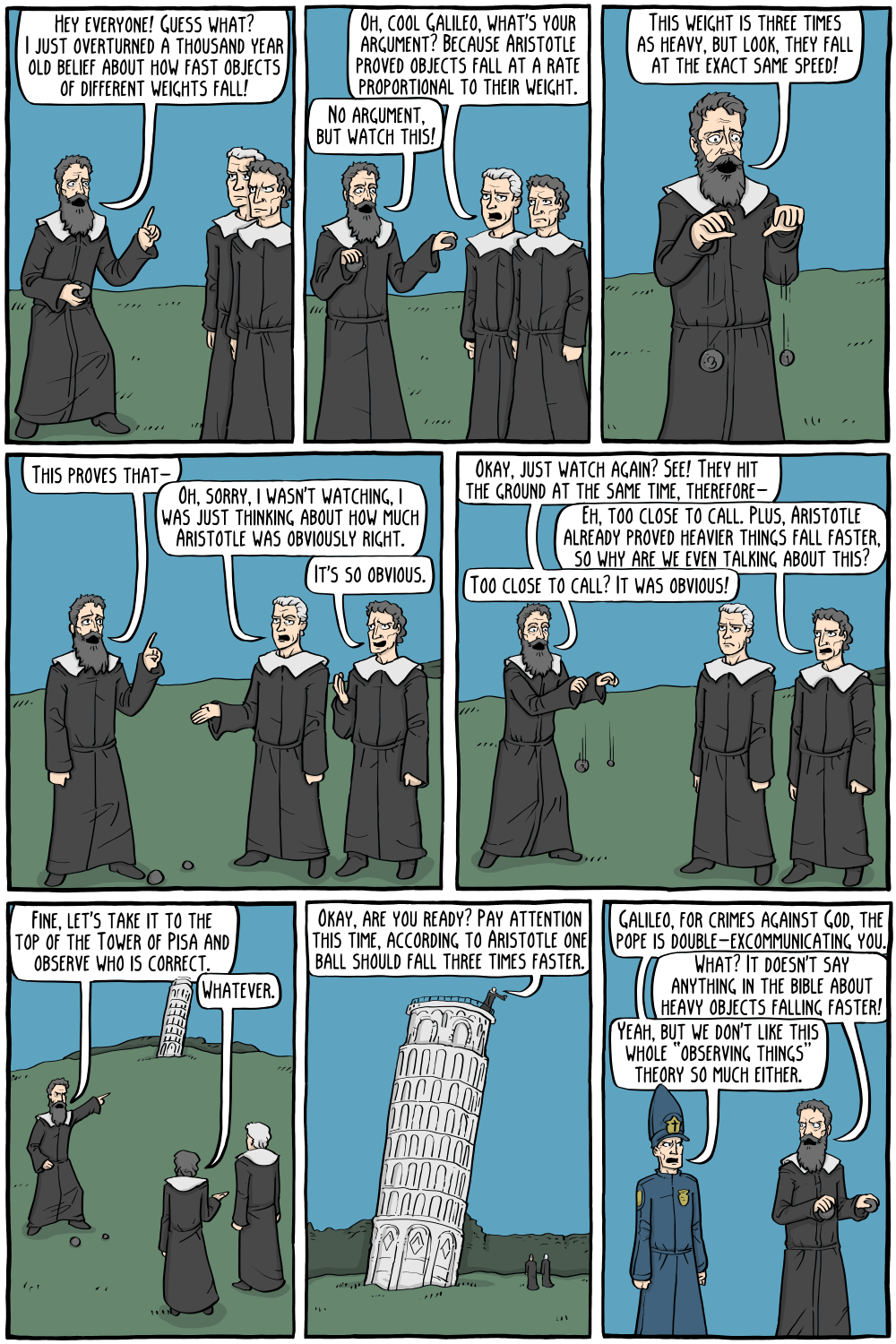

It seems like this is simultaneously a principle that everyone must have already learned as children, but somehow also a controversial opinion among learned people; much like empiricism, the radical proposition that we can learn things about the world by looking at it:

-

Isaac

10.3kIt seems like this is simultaneously a principle that everyone must have already learned as children, but somehow also a controversial opinion among learned people — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kIt seems like this is simultaneously a principle that everyone must have already learned as children, but somehow also a controversial opinion among learned people — Pfhorrest

Give us an example then. What philosophical approach denies that you can find out what feels bad for others by putting yourself in their shoes? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kNobody I know of denies that you can, but plenty of people, anyone opposed to altruism or hedonism, denies that it matters to: anti-altruists denying that other people's anything matters, anti-hedonists denying that anybody's appetites matter.

Pfhorrest

4.6kNobody I know of denies that you can, but plenty of people, anyone opposed to altruism or hedonism, denies that it matters to: anti-altruists denying that other people's anything matters, anti-hedonists denying that anybody's appetites matter.

Like how nobody denies that you can look at Galileo dropping his rocks and see for yourself that they land at the same time, but some will talk as though that doesn't matter, because "the senses are deceitful and can't be trusted", something something Plato's cave, shadow puppets, light of reason, etc. -

Isaac

10.3kNobody I know of denies that you can, but plenty of people, anyone opposed to altruism or hedonism, denies that it matters to: anti-altruists denying that other people's anything matters, anti-hedonists denying that anybody's appetites matter. — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kNobody I know of denies that you can, but plenty of people, anyone opposed to altruism or hedonism, denies that it matters to: anti-altruists denying that other people's anything matters, anti-hedonists denying that anybody's appetites matter. — Pfhorrest

Right. But that's the meta-ethics bit.

So when you say...

I am of the peculiar opinion that applied ethics is not properly speaking a branch of philosophy at all, but is rather the seed of an entire field of underdeveloped ethical sciences — Pfhorrest

What you actually mean is just that you don't agree with those meta-ethical positions.

Afterall, if you take the moral good to be the word of God, then applied ethics is exactly what those people think it is.

If, however, you take the moral good to be that which meets all hedonic appetites in any given circumstance, then it follows logically that finding out what that is would constitute applied ethics. And, as you say, no-one would disagree with you about that.

So what exactly is the novel approach here? It all seems to logically follow from your stated meta-ethical position in a way which you've just admitted no-one would disagree with.

As usual you're expending pages and pages explaining that with which no-one disagrees and presenting very little new angle on the actual matter of substantive disagreement, which are the flaws in your meta-ethical position.

No doubt that's 'to come later' again? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe matter of substantial disagreement is on whether or not experience, everyone’s experiences, are relevant and important and matter, which was covered and argued for many threads ago.

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe matter of substantial disagreement is on whether or not experience, everyone’s experiences, are relevant and important and matter, which was covered and argued for many threads ago.

If that is accepted then the rest should follow for anyone who can keep up with the logic (which NB does have novel implications as well as drawing novel connections between disparate well-known things).

If that argument from many threads ago is not accepted then I lost you way back then and pointing out that you (or someone) still disagree with that isn’t getting anyone anywhere. If I lost you (generic you, whomever) way back there then I have no further ideas on how to reach you, so I’m not talking to you anymore. -

180 Proof

16.4k

180 Proof

16.4k

I disagree. The sciences I've mentioned also explain optimal functioning of its subjects (agents) and therefore prescribe in situ strategies for avoiding or correcting suboptimization (e.g. ill-health/morbidity; unsustainable commons/negative sum conflicts; and maladaptive vices/pathologies, respectively). 'Subjective data' do not inform those models sufficiently enough to improve their explanatory powers or predictive efficacy. As far as I can tell, Pfhorrest, each is an example of an objective (i.e. subjectivity / pov-invariant for the most part) theoretical discourse.So "ethical science" is like medical science or human ecology (my preferred analogue) or moral psychology ...

— 180 Proof

I’m not sure that’s accurate, since AFAIK those fields are empirical investigations, that at most describe what people are like and how they react to various things, in the third person. — Pfhorrest

A prescriptive science, structured from intrinsic – domain specific – hypothetical imperatives (e.g. if optimal health, then maintain homeostasis by ... ), is what I understand when you call for "ethical science". I don't think social sciences like e.g. anthropology, sociology, economics, etc are adequately prescriptive analogues for any ethics (except, maybe, descriptive ethics). In so far as we seek a universal, or objective, framework for ethical judgment (meta) and moral conduct (normative & applied), it will consist of facts about humans as a species and human agency which are true regardless of how we (in/directly) experience or (mis)learn "right & wrong". -

Isaac

10.3k

Isaac

10.3k

Leaving a fundamental flaw unresolved and pushing on with the detailed implications nonetheless seems rather like ignoring a gap in one's foundations and continuing to build the house, but that to one side, the issue I wanted some clarity on is...

If that is accepted then the rest should follow for anyone who can keep up with the logic (which NB does have novel implications as well as drawing novel connections between disparate well-known things). — Pfhorrest

We'd just established that no-one would disagree with them. That doesn't sound novel.

What are these novel implications? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kWe established that no-one would disagree that you CAN learn what feels good or bad to other people by “walking a mile in their shoes” etc. The disagreement is about whether it MATTERS TO. And that’s not an implication at this point in the process, that’s a premise now, after having been established way back at the beginning, whether to your satisfactory or not. I have not seen any convincing counter arguments to those foundational principles established way back then, only what amounts to either a misunderstanding of them or the assertion that someone disagrees with them.

Pfhorrest

4.6kWe established that no-one would disagree that you CAN learn what feels good or bad to other people by “walking a mile in their shoes” etc. The disagreement is about whether it MATTERS TO. And that’s not an implication at this point in the process, that’s a premise now, after having been established way back at the beginning, whether to your satisfactory or not. I have not seen any convincing counter arguments to those foundational principles established way back then, only what amounts to either a misunderstanding of them or the assertion that someone disagrees with them.

The novel idea in this thread isn’t even an implication of those principles, the version of it I’m putting forth merely assumes the rest of my views, but in principle could be adapted to others. That idea in this thread is:

There are two parts to an ethical investigation, the philosophical part of figuring out what we’re asking, what would make an answer correct, and how we apply such criteria; then the part where we actually do that application and come up with specific answers for the real world based on those philosophical principles. Meta-ethics is the first part, applied ethics is the start of the second part, and normative ethics kinda doesn’t fit in there anywhere. But different normative ethical views are on the right track to answering different meta-ethical questions, and the whole sort of project normative ethics is trying to do is really the base layer of what applied ethics should become. -

baker

6k

baker

6k

Why on earth would anyone do that???To find out what's good or bad, walk some miles in other peoples' shoes, put yourself in their places, experience for yourself what it's like to go through what they go through, and if necessary figure out what's different between you and them that might account for any differences that remain in your experiences. — Pfhorrest

Would you empathize with Hitler, see things from his perspective, see, how from his perspective, what he did was good and right? Exactly.

Apart from such extreme empathy being impossible to do, what should the purpose be for it? Extreme tolerance? Annulment of responsibility? Extreme egalitarianism?

And what would such extreme empathy have to do with finding out what's good or bad??

No. What children are taught isn't empathy, it is projection under the guise of empathy.It seems like this is simultaneously a principle that everyone must have already learned as children,

The whole idea is remiss anyway, as small children aren't even able to reason about morality in terms of empathy. See Kohlberg's stages of moral development. A person cannot relate to a moral reasoning that is outside of the stage they're in. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI think perhaps there's just a misunderstanding. I'm not saying that those fields you're talking about aren't relevant at all in the end, but that they're still only part of one half of the picture, and what I'm talking about in this thread is the insufficiently examined other half of that same picture.

Pfhorrest

4.6kI think perhaps there's just a misunderstanding. I'm not saying that those fields you're talking about aren't relevant at all in the end, but that they're still only part of one half of the picture, and what I'm talking about in this thread is the insufficiently examined other half of that same picture.

When we're setting out to do anything, there's two things to ask ourselves: why to do it / why should something come to be the case, and how to do it / how does something come to be the case? We've got all of the descriptive sciences, including the ones you're talking about, investigating the second type of question, the "how does", to great results. But we barely have any systemic investigation into the first question, the "why should". That's what I'm on about here. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kWould you empathize with Hitler, see things from his perspective, see, how from his perspective, what he did was good and right? — baker

Pfhorrest

4.6kWould you empathize with Hitler, see things from his perspective, see, how from his perspective, what he did was good and right? — baker

Yes, but not to agree with him, but to understand his deeper motives and find alternate ways of satisfying them that don't so deeply dissatisfy others'.

Extreme egalitarianism? — baker

Yes, otherwise known as altruism. Everyone matters. Everyone.

And what would such extreme empathy have to do with finding out what's good or bad?? — baker

What do you think "good or bad" even mean? Because this just sounds like a bizarre question to me. -

baker

6k

baker

6k

Then you wouldn't be "walking in his shoes" to begin with. You wouldn't be empathizing, you'd be projecting, following your own agenda.Yes, but not to agree with him, but to understand his deeper motives and find alternate ways of satisfying them that don't so deeply dissatisfy others'. — Pfhorrest

If you're already sure you know what's right and wrong, then why randomly empathize with others??

No. For one, this is not how the world works.Extreme egalitarianism?

— baker

Yes, otherwise known as altruism. Everyone matters. Everyone.

For two, what you're describing sounds more like codependence or borderline personality disorder symptoms.

You're not answering my question.And what would such extreme empathy have to do with finding out what's good or bad??

— baker

What do you think "good or bad" even mean? Because this just sounds like a bizarre question to me.

Do you believe in objective morality? -

baker

6k

baker

6k

Because for a psychologically normal person, the Why is supposed to go without saying, be something that the person takes for granted.When we're setting out to do anything, there's two things to ask ourselves: why to do it / why should something come to be the case, and how to do it / how does something come to be the case? We've got all of the descriptive sciences, including the ones you're talking about, investigating the second type of question, the "how does", to great results.

But we barely have any systemic investigation into the first question, the "why should". — Pfhorrest -

180 Proof

16.4kYeah, and that's because "the why" belongs to philosophical speculation and not to scientific /model-theoretic explanation. My concession to 'the need' for that "why" in a scientific context is mentioned here:

180 Proof

16.4kYeah, and that's because "the why" belongs to philosophical speculation and not to scientific /model-theoretic explanation. My concession to 'the need' for that "why" in a scientific context is mentioned here:

Philosophically I'm committed to there not being any (ultimate) 'why that does not beg the question' (precipating infinite regresses); so well-tested, validly inferred heuristic / causal "hows" suffice in the breach.A prescriptive science, structured from intrinsic – domain specific – hypothetical imperatives (e.g. if optimal health, then maintain homeostasis by ... ) — 180 Proof -

Pfhorrest

4.6kthis is not how the world works. — baker

Pfhorrest

4.6kthis is not how the world works. — baker

When talking about how the world should be, saying "but it's not that way" is non-sequitur.

Do you believe in objective morality? — baker

Objective as in universal, non-relative, yes.

Objective as in transcendent, non-phenomenal, no.

I'm about to go into why on each of those in my next thread, though I already have in brief in a much earlier thread.

Because for a psychologically normal person, the Why is supposed to go without saying, be something that the person takes for granted. — baker

"the why" belongs to philosophical speculation — 180 Proof

Speculation is not philosophy, and if you think all can be said about something is unsubstantiated speculation or something else unquestionable and just taken for granted, then you’re just declaring that the question cannot actually be answered, or that the answers cannot be questioned, either of which is merely to give up trying to answer it, which is counter to the first principles of my philosophy, the application of which to morality I’ve already gone over in brief (see earlier thread) and which I’ll be exploring in more depth in my next thread.

Philosophically I'm committed to there not being any (ultimate) 'why that does not beg the question' (precipating infinite regresses) — 180 Proof

There is equal potential for infinite regress in the “how does” question, and the solution to both is the same: more or less, critical rationalism, i.e. letting any possibility float until it can be ruled out, rather than rejecting all possibilities until they can be proven the unique correct one. The application of that principle to morality is three threads away, though it's also already been covered briefly in that earlier thread.

Then you wouldn't be "walking in his shoes" to begin with. You wouldn't be empathizing, you'd be projecting, following your own agenda. — baker

Walking in someone's shoes doesn't at all mean you have to agree with them, it just means you care about their experiences. If they don't care about other people's experience, they might make morally wrong decisions, so you shouldn't agree with them, even though you understand where they're coming from, as you should, because if you don't care about their experience, then you might make the morally wrong decisions too. To approach a universally ("objectively") correct opinion about anything requires accounting for the phenomenal ("subjective") experiences of as close to everyone as you can manage.

If you're already sure you know what's right and wrong, then why randomly empathize with others?? — baker

I'm not already sure I know what is right and wrong, I'm just confident about what the criteria for assessing what's right and wrong are. (Those criteria involve the experiences that everybody has, and Hitler's decisions did not respect those criteria, which is why I judge them wrong; but assessing what would have been right would still have involved considering his experiences too.)

This is the only part of this post or those I'm responding to that's actually on topic to this thread: there are separate issues of how to answer moral questions in principle, and what are those answers given the specifics of the real world. Meta-ethics (moral semantics, moral ontology, moral epistemology, etc) is about the first issue, applied ethics is about the second issue, and normative ethics messily blurs those lines, does both badly, and should be split up among the other two, only the first of which is philosophical, because it's about necessary a priori principles, while the latter is about contingent a posteriori matters, and so beyond the scope of philosophy.

You're not answering my question. — baker

Because it's not the topic of this thread, and also it's a prima facie dumb question like asking "what do numbers have to do with math?" (Credit to my gf who saw your question over my shoulder and said exactly that).

For two, what you're describing sounds more like codependence or borderline personality disorder symptoms. — baker

This sounds like you're lashing out at me suggesting you being scared of non-binary people is a psychological problem of yours, not a social problem of theirs.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum