-

Kaiser Basileus

52Math rests on the same foundation as logic - it keeps working. It has, as far as we can tell, always worked, and will, as far as we can tell, continue to work. As long as the sun keeps rising, there's no reason to question it. Our purposes are met by using these tools. That's how we know they're good tools, not because they're true in some esoteric transcendent sense (which we cannot know).

Kaiser Basileus

52Math rests on the same foundation as logic - it keeps working. It has, as far as we can tell, always worked, and will, as far as we can tell, continue to work. As long as the sun keeps rising, there's no reason to question it. Our purposes are met by using these tools. That's how we know they're good tools, not because they're true in some esoteric transcendent sense (which we cannot know). -

Kaiser Basileus

52Justified "true" belief is a step too far. If everyone in the entire species thought something was a fact and it turned it not to be, it would still have been true "for all intents and purposes" until the new information came to light. Hypothetical future changes are an unknown unknown and so can never be accounted for.

Kaiser Basileus

52Justified "true" belief is a step too far. If everyone in the entire species thought something was a fact and it turned it not to be, it would still have been true "for all intents and purposes" until the new information came to light. Hypothetical future changes are an unknown unknown and so can never be accounted for.

I'm a relativist, yes, but that doesn't mean arbitrary. The truth isn't relative to imaginary transcendent knowledge, but to our best attempts at verification.. "for all intents and purposes.

As for numbers; math is descriptive of the relationships between idealised entities that do not exist in reality. -

Banno

30.6kjust to be sure, is twice two is four true because it is useful, or because four is just what we mean by twice two?

Banno

30.6kjust to be sure, is twice two is four true because it is useful, or because four is just what we mean by twice two? -

Kaiser Basileus

52Both. We have the semantic version only because it keeps working that way. The ontological answer is that individual things do not exist until and for a particular purpose. But i'm feeling like i'm not tracking this conversation very well right now and this could go a million directions. tiny.cc/realityis tiny.cc/ontology and tiny.cc/epistemology hold the foundational elements of what i'm getting at. There is no Practical difference in why or how these things work. But a lot of things become clear when we understand that our intentions set the framework in which all else matters. Man is not the measure of all things precisely, man is the measurer of all things. Until then it's just stuff. Unless we're trading physical stuff, math doesn't have a purpose, and so forth.

Kaiser Basileus

52Both. We have the semantic version only because it keeps working that way. The ontological answer is that individual things do not exist until and for a particular purpose. But i'm feeling like i'm not tracking this conversation very well right now and this could go a million directions. tiny.cc/realityis tiny.cc/ontology and tiny.cc/epistemology hold the foundational elements of what i'm getting at. There is no Practical difference in why or how these things work. But a lot of things become clear when we understand that our intentions set the framework in which all else matters. Man is not the measure of all things precisely, man is the measurer of all things. Until then it's just stuff. Unless we're trading physical stuff, math doesn't have a purpose, and so forth. -

Banno

30.6kthinking about it, things can be true just because they are useful. There are useful lies. So maths can’t be true just because it is useful. It must be true even without stuff.

Banno

30.6kthinking about it, things can be true just because they are useful. There are useful lies. So maths can’t be true just because it is useful. It must be true even without stuff. -

Kaiser Basileus

52Maths doesn't even exist beyond useful. There's no way to strictly delineate one thing from another, so individuation is subject to the same rule. There's only numbers to the extent we use things distinctly. There's one apple to someone interested in one apple, but there's only the barrel to someone interested in making applesauce. Likewise there is no zero/nothing in reality, only the lack of specific things in context. Math, in other words, is about organising our experience and relies upon nothing else. There's no reason to believe it exists anywhere else or any way else.

Kaiser Basileus

52Maths doesn't even exist beyond useful. There's no way to strictly delineate one thing from another, so individuation is subject to the same rule. There's only numbers to the extent we use things distinctly. There's one apple to someone interested in one apple, but there's only the barrel to someone interested in making applesauce. Likewise there is no zero/nothing in reality, only the lack of specific things in context. Math, in other words, is about organising our experience and relies upon nothing else. There's no reason to believe it exists anywhere else or any way else. -

Banno

30.6kSo if it proved useful

Banno

30.6kSo if it proved useful

To say one plus one equals one, that would be fine? One drop of rain meeting one more drop makes one drop? -

Kaiser Basileus

52Both. We have the semantic version only because it keeps working that way. The ontological answer is that individual things do not exist until and for a particular purpose. But i'm feeling like i'm not tracking this conversation very well right now and this could go a million directions. tiny.cc/realityis tiny.cc/ontology and tiny.cc/epistemology hold the foundational elements of what i'm getting at. There is no Practical difference in why or how these things work. But a lot of things become clear when we understand that our intentions set the framework in which all else matters. Man is not the measure of all things precisely, man is the measurer of all things. Until then it's just stuff. Unless we're trading physical stuff, math doesn't have a purpose, and so forth.

Kaiser Basileus

52Both. We have the semantic version only because it keeps working that way. The ontological answer is that individual things do not exist until and for a particular purpose. But i'm feeling like i'm not tracking this conversation very well right now and this could go a million directions. tiny.cc/realityis tiny.cc/ontology and tiny.cc/epistemology hold the foundational elements of what i'm getting at. There is no Practical difference in why or how these things work. But a lot of things become clear when we understand that our intentions set the framework in which all else matters. Man is not the measure of all things precisely, man is the measurer of all things. Until then it's just stuff. Unless we're trading physical stuff, math doesn't have a purpose, and so forth. -

Banno

30.6kProblems with the OP: One.

Banno

30.6kProblems with the OP: One.

Epistemology is all about certainty, not “Truth”. — Kaiser Basileus

There is a sense in which we can be rid of truth. After all, "Twice two is four" and "'Twice two is four' is true" have the exact same truth conditions. The addition of "...is true" does not change the truth value.

But the addition of "...is certain" might change the truth value. That's because certainty is an attitude adopted by someone towards a statement, and so quite a different animal to truth. Certainty is a state of mind. Truth isn't. -

Banno

30.6kProblems with the OP: Two

Banno

30.6kProblems with the OP: Two

Firstly, why prefix the word "real" to "truth"? Are there unreal truths? Not a big point, but it leaves one somewhat suspicious...Real Truth is inaccessible to us because of physical and mental filters between us and the real world, namely biological, cultural, and psychological. — Kaiser Basileus

Secondly, this seems to be an example of Stove's Gem:

We can know things only- as they are related to us

- under our forms of perception and understanding

- insofar as they fall under our conceptual schemes,

- etc.

- we cannot know things as they are in themselves.

Plain, ordinary truths are transparently available to us. It is true that I am writing this on my laptop. It is true that I am writing in English. It is true that while I write this the cat is on the modem, keeping its feet warm. These are not extraordinary things in need of epistemic investigation.

In conclusion, playing epistemological games with words takes us away from the way we ordinarily use notions such as "...is true". That's why @Kaiser Basileus needs the modifier "Real truth"; it marks the place were we leave our ordinary understanding of truth behind, and start to play a different game with the same words. -

Banno

30.6kProblems with the OP: Three

Banno

30.6kProblems with the OP: Three

A trite observation, perhaps: Is the sentence "There are only two ways of knowing, empirical probability and logical necessity" itself known empirically, or is it a logical necessity?There are only two ways of knowing, empirical probability and logical necessity. — Kaiser Basileus

I can't see any way of assigning truth values to it to determine if it is a tautology, and hence known by logical necessity.

So is it empirical? Is it perhaps falsifiable? Well, I know I love Wife; such self-knowledge seems to be neither empirical nor tautologous... So, debatably, it stands falsified. I know how to ride a bike. Is that knowledge empirical nor tautologous?

In any case, it is by no means obvious that we ought accept that there are only two ways of knowing.

Some claim a third, revelation, but this cannot be tested or adequately expressed externally and cannot therefore be verified as reliable. — Kaiser Basileus

This is the criteria for rejecting revelation seems equally applicable to "There are only two ways of knowing, empirical probability and logical necessity". It cannot be tested or adequately expressed externally and cannot therefore be verified as reliable...

(Here I am supposing that "adequately expressed externally" is somehow like being logically true. If that's wrong, enlighten me). -

Banno

30.6kMore on the first problem:

Banno

30.6kMore on the first problem:

The first issue is, if epistemology is about certainty, and not abut truth, what are we to do with truth? Should we stop using it altogether? Can we replace every instance of "is true" with "is certain" without loss?

(My italics).Empirical probability is the realm of science. It is that things keep happening the same way. As we increase the resolution of our instruments, either outward/upward or downward/inward, we effectively increase the size of our reality as well as the level of certainty we can have about it. We increase truth, for all intents and purposes. — Kaiser Basileus

But here it is clear that it is difficult to remove truth entirely. That being true and being certain are not the same thing, is implicit in the setting out of the argument here.

The salient point is that, at the least, it is not a simple task to remove truth from epistemology. -

Banno

30.6kProblems with the OP: Four

Banno

30.6kProblems with the OP: Four

The logical premise that makes this necessarily true is based on the identical foundation as science - it keeps working. — Kaiser Basileus

This seems to be saying that tautologies are only true because they are useful. That interpretation is upheld by Kaiser's answers to my questions, above. So:

Math rests on the same foundation as logic - it keeps working. — Kaiser Basileus

But tautologies are true because of their structure. Modus ponens is true regardless of how useful it is. further, and consider this with care, modus ponens can only be useful under a given interpretation; yet an interpretation in which modus ponens were not useful must by that very fact be wrong. An interpretation in which modus ponens appears to fail provides us with a reductio ad absurdum, and hence leads to the conclusion that one of the assumptions is wrong; that is, the interpretation has failed.

Logic is not true because it is useful; rather, it is useful because it shows what can be true. -

Banno

30.6kProblems with the OP: Five

Banno

30.6kProblems with the OP: Five

(My italics)Statistics is a way of quantifying our level of certainty, whether in science replicability or emotional anecdote. — Kaiser Basileus

Is the suggestion here that one's preference for vanilla over chocolate is a result of some explicit Bayesian analysis?

I don't.

There's something more than just odd about the idea of employing a statistician in order to decide if you should propose to your significant other. But:

When you have an average level of certainty sufficient to outweigh other options, this is called epistemological warrant. It means that you are justified in making the decision or in accepting the fact as true. — Kaiser Basileus -

Banno

30.6kMore on Problem two:

Banno

30.6kMore on Problem two:

Here's that divide between the inside and the outside writ large:

To the extent we use patterns internally, internal versions of words suffice and they need only be internally consistent sufficient for internal purposes. To be used externally, they must be externally consistent (that is, accurately represent the material/sensable/testable world sufficient for whatever purpose they’re being used toward), and the extent to which we agree on them is the extent to which we can communicate effectively. — Kaiser Basileus

It will not do to just assume that there is a private world and a public world, and never the twain shall meet. The arguments here are long and windy, but in the end it seems incontrovertible that any private world is itself a public construction.

Further, it is this assumed segregation of mental life from the world that leads to Stove's Gem.

Reject the Cartesian notion of mind as the only source of certainty and you may have no need to explain how we bridge the imaginary gap between the mental and the physical. -

Kaiser Basileus

52That's easy enough. (tiny.cc/epistemology) The external/physical/material world is that which we access through our senses.

Kaiser Basileus

52That's easy enough. (tiny.cc/epistemology) The external/physical/material world is that which we access through our senses. -

creativesoul

12.2kSecondly, this seems to be an example of Stove's Gem:

We can know things only

as they are related to us

under our forms of perception and understanding

insofar as they fall under our conceptual schemes,

etc.

So,

we cannot know things as they are in themselves. — Banno

I recently witnessed an introduction to philosophy professor who actually put forth this argument.

:gasp:

I was helping an intro student, so I ignored it(didn't call it out) and offered him something entirely different. Talk about trees always works. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

I've seen it used to great effect in intro philosophy; it quickly separates the goats and sheep. The goats get to do Honours. The sheep don't get past first year.

Many sheep wind up here, arguing for relativism or pragmatism. -

creativesoul

12.2kWell, the student maintained their average. They've never had less than an "A". I had to be very careful how I spoke though, for my understanding is not at an intro level so, I spoke of trees. Simple, effective, and damn near irrefutable if done right. My friend understood quite easily without ever doubting anything other than "why can't we know about trees?" I, of course, replaced some ambiguous notion with "trees" because it satisfied the notion and simplified the talk. Poor student was rather confused until then. The student just needed a social science credit, or something like that, so no more philo for them. Science major... -

numberjohnny5

179Epistemology is all about certainty, not “Truth”. — Kaiser Basileus

numberjohnny5

179Epistemology is all about certainty, not “Truth”. — Kaiser Basileus

No. Epistemology is about the nature of knowledge and how we acquire it. -

Banno

30.6kThat's easy enough. (tiny.cc/epistemology) The external/physical/material world is that which we access through our senses. — Kaiser Basileus

Banno

30.6kThat's easy enough. (tiny.cc/epistemology) The external/physical/material world is that which we access through our senses. — Kaiser Basileus

I'm not at all sure to what this refers - or even if it was directed at me.

But I winder if Proprioception is internal or external. How do I know where my foot is?

Yet Proprioception is a sense.

All up, I think we can conclude that epistemology is not as simple as you supposed. -

jorndoe

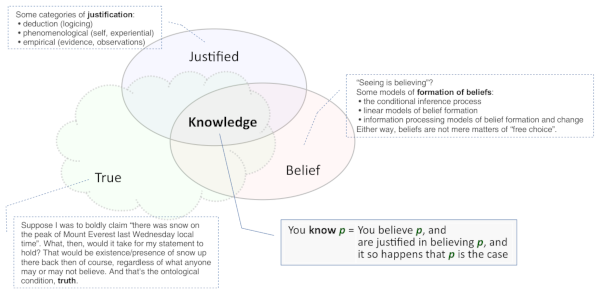

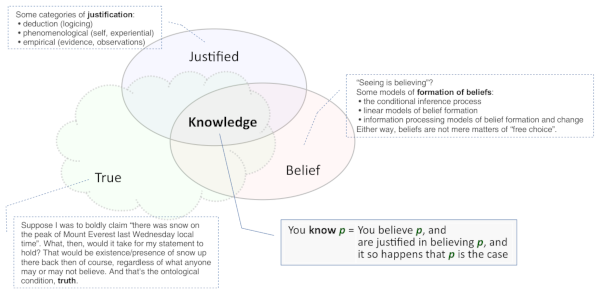

4.2kIs this more traditional sketch reasonable?

jorndoe

4.2kIs this more traditional sketch reasonable?

(the attached knowledge-traditional-1247x610.png is easier to read)

Belief » Formation (Wikipedia)

(Yes yes, the Gettier cases, but they're more a refinement, than a reason to bin it all.)

So, that's not so much about know-how, as it is about propositional knowledge.

Seems the work lies in justification. -

creativesoul

12.2k

Gettier gets believing a disjunction wrong. That's all his second case amounts to, nothing more. His first case is an example of his changing the truth conditions of Smith's belief when he invokes "the man with ten coins in his pocket"... unacceptable change.

Anyway, the OP here seems a bit lost. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Even Plato realised that the justified true belief account was inadequate ; just flatus, he says.

But @Sam26will give a good defence of it; worth listening to.

Better to treat knowing-that as a special case of knowing-how; that is, there is only one sort of knowledge, performative knowledge, knowing how to do something like ride a bike or play a guitar; or produce an argument or give a command or write an essay.

All knowledge reduces to knowing how to do something.

Hence, you demonstrate that you are knowledgeable by doing stuff. -

Banno

30.6kFurther, we act within the confines of reality; there are things we cannot do, despite what we want or believe. And that's an absolute, regardless of probability and to the annoyance of any epistemic relativists.

Banno

30.6kFurther, we act within the confines of reality; there are things we cannot do, despite what we want or believe. And that's an absolute, regardless of probability and to the annoyance of any epistemic relativists.

If the battery is flat, no amount of Bayesian analysis or linguistic interpretation will charge it. You have to buy a new one or charge it.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum