-

Agustino

11.2kFrom here.

Agustino

11.2kFrom here.

Thanks to @Wayfarer for providing THIS ARTICLE.

I've read the interview, but it all seems to be a "back to Hume" moment. The problem with that for me, is that there are some concepts which we do not encounter in experience, but which are nevertheless necessary for that experience to be possible in the first place. So I take the Kantian route here...

For example - individuation. Individuation - that we see experiences as individual, and separate from one another, that we can even make such distinctions as red, blue, etc. - we don't get this concept from any one experience, or any multitude of experiences. Instead, in order to have more than one experience in the first place, individuation already must be possible. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI don't really see the point. Words in the mind are representations of the physical things. This makes them memories. If the question is where are memories, or how do memories exist, then this is a larger issue, one without an adequate answer. And it's not even close to being answered because we have no adequate understanding of the difference between the past (memories) and the future (anticipations).

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI don't really see the point. Words in the mind are representations of the physical things. This makes them memories. If the question is where are memories, or how do memories exist, then this is a larger issue, one without an adequate answer. And it's not even close to being answered because we have no adequate understanding of the difference between the past (memories) and the future (anticipations).

So the use of words within the mind is an application of the past (memories) toward the future (anticipation). And we really have no idea of how memories differ from anticipations because we have no idea of how the past differs from the future. Focusing on the existence of words in the mind, which is clearly a unity of memory and anticipation will only enhance the ambiguity and confusion which exists in relation to this issue.

For example - individuation. Individuation - that we see experiences as individual, and separate from one another, that we can even make such distinctions as red, blue, etc. - we don't get this concept from any one experience, or any multitude of experiences. Instead, in order to have more than one experience in the first place, individuation already must be possible. — Agustino

I agree that individuation, or the capacity to individuate, is necessarily prior to the capacity to use words, and therefore prior to language in general. This is evident from the fact that in order to understand a statement we need to be able to individuate the words. Despite the fact that the statement is understood as a comprehensive "whole", this is a synthesis which only follows from analysing the parts individually and their relations to the other parts.

This appears to be a reflection of how we understand the world around us in general. We recognize, and come to understand individual things, objects, which though they are recognized as individuals, we still apprehend them as parts of a whole, so we proceed to understand their relationships with other individual objects. Since we apprehend the individuals as parts of a whole, we are driven to recreate that whole, as "the world", or "the universe", in synthesis, to further our understanding, just like we recreate "the statement" as a whole.

What people often fail to grasp is that the whole "the world" or 'the universe", which is referred to by these words is synthetic in this sense. We always understand composites by breaking them down into parts, then rebuilding the relationships in conceptual form, so that our understanding of such unities is always backward to their natural occurrence. It is always based in an analysis or deconstruction of the object, and this is backward to the creation of the object. -

Agustino

11.2k

Agustino

11.2k

That's already obfuscation. The point of the article was that "words" are actually physical sounds. So they are not representations at all. So when I hear "apple", I experience the idea of apple - because there is a constant conjunction, due to habit, between hearing apple (experience 1) and feeling the conjoined properties of an actual apple, however vague (experience 2). So we're back to the Humean understanding where there are impressions and ideas (which are nothing but copies of impressions). Otherwise, we have the problem of explaining how it is that a sound can represent a taste + a sight + all the rest.Words in the mind are representations of the physical things. — Metaphysician Undercover

If that is the case, then we have a bit of a problem, because it seems that we have ideas for which there are no corresponding impressions. For we never have an impression of, for example, individuation. It is true that the impressions which we do have are individuated, but where is the impression of individuation itself? So then either individuation is a concept that emerges from other concepts (space, time, etc.) or it is a primary concept itself. From whence does such a concept originate? What does it mean to say that our mind has a capacity to abstract this concept from the impressions themselves? And if we were to say that, then it would follow that we do know something a priori about the impressions, namely that they are by necessity individuated.

Memory itself is another obfuscation. All that I mean by memory is precisely the habit of experiencing an actual apple however vaguely, everytime I hear the sound "apple". So memory is formed precisely of this constant conjunction - that is what memory is. Now the real question is why is there such a constant conjunction through time? Just cause our mind associates impressions that occur together with each other? And if so, what is this "mind" of ours, and why does it happen to have this property to associate impressions? -

Agustino

11.2kFrom another interview:

Agustino

11.2kFrom another interview:

But the implications of this “official” view are profound. First it suggests our perceptions are radically separate from the external world, fenced off inside the skull. Second, and as a result, that we all live in error and need the authority of science to tell us what reality is really like. So it gives scientists considerable power. — Parks (with my bolds)Right, so maybe what we need to do is to get beyond the idea that consciousness is a “representation” of the world at all. Maybe it is simply reality. Maybe, as I hinted at the beginning, we have to do away with that subject/object distinction which lies behind this whole discussion. — Manzotti -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThe point of the article was that "words" are actually physical sounds. So they are not representations at all. — Agustino

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThe point of the article was that "words" are actually physical sounds. So they are not representations at all. — Agustino

That's not at al what the article actually says:

So, direct perception of sights and sounds in the world outside the body are very quickly ordered and colored by language inside our heads. “Once a thing is conceived in the mind,” wrote the poet Horace in the first century BC, “the words to express it soon present themselves.” And we call this thinking. All our experience can be reshuffled, interconnected, dissected, evoked, or willfully altered in language, and these thoughts are then stored in our brains.

Notice in particular the phrases "language inside our heads", and "we call this thinking".

So when I hear "apple", I experience the idea of apple - because there is a constant conjunction, due to habit, between hearing apple (experience 1) and feeling the conjoined properties of an actual apple, however vague (experience 2). So we're back to the Humean understanding where there are impressions and ideas (which are nothing but copies of impressions). Otherwise, we have the problem of explaining how it is that a sound can represent a taste + a sight + all the rest. — Agustino

This is actually where the obfuscation is, because the article is talking about words within our heads. Now you have jumped immediately to what the words are associated with in our minds, instead of considering what the author wants us to consider, and that is the existence of the words themselves within our minds.

The rest of your post, concerning individuation is irrelevant now, because individuation is already implied, as a necessary condition, for the existence of words in our heads. The words exist as individuals within our minds, and we can scramble them around creating different combinations in the process of thinking. What any particular word is associated with, what you call the "impression", is dependent on the combinations which one creates by scrambling the words around in one's head.

Memory itself is another obfuscation. All that I mean by memory is precisely the habit of experiencing an actual apple however vaguely, everytime I hear the sound "apple". So memory is formed precisely of this constant conjunction - that is what memory is. Now the real question is why is there such a constant conjunction through time? Just cause our mind associates impressions that occur together with each other? And if so, what is this "mind" of ours, and why does it happen to have this property to associate impressions? — Agustino

You don't seem to apprehend the fact that the mind creates these associated impressions. So any such "constant conjunction through time", is just what the mind has created, and it need not be constant. This is very evident from the fact that an individual's memory of a certain event will change as time passes, such that an event from last week will be remembered in a particular way, but if the person still remembers that event in thirty years from now, the memory will most likely not be the same. That is because to remain the same, the memory must be recollected in the exact same way each time.

The description of memory as "a constant conjunction through time", therefore is not accurate. Memory is better described in terms of repetition. We repeat to ourselves, often using words, over and over again, what has happened, and this is the act of remembering. So memory is really an habitual act. The fact that our memories change over time indicates that memory is not a case of putting something somewhere and later recollecting it, it is a case of knowing how to reproduce that activity of recollecting. -

Agustino

11.2k

Agustino

11.2k

That's what Tim Parks says, I don't care about him. He's interviewing the other guy. What the other guy says matters, Tim is just making noise there.That's not at al what the article actually says: — Metaphysician Undercover

And you ought to notice how the other guy corrects him. So read it more carefully, I can't do that for you.Notice in particular the phrases "language inside our heads", and "we call this thinking". — Metaphysician Undercover

Parks: But we were talking about words, Riccardo, not sofas and armchairs! Last time we talked about thinking things directly; this time we’re considering thinking in language, which is surely different.

Manzotti: Not at all. Words are really not so different from sofas and armchairs. They are external objects that do things in the world and, like other objects, they produce effects in our brains and thus eventually, through us, in the world. The only real difference is that, when it comes to what we call thinking, words are an awful lot easier to juggle around and rearrange than bits of furniture.

Nope.This is actually where the obfuscation is, because the article is talking about words within our heads. — Metaphysician Undercover -

Agustino

11.2k

Agustino

11.2k

No, the mind is a no-thing as far as I'm concerned. What is "mind"? Until it's clarified what that even means, you're saying nonsense by the "mind" creates.You don't seem to apprehend the fact that the mind creates these associated impressions. — Metaphysician Undercover

Yes, so this constant conjunction isn't always the same. There must be an input from the imagination to fill in gaps of vagueness.This is very evident from the fact that an individual's memory of a certain event will change as time passes, such that an event from last week will be remembered in a particular way, but if the person still remembers that event in thirty years from now, the memory will most likely not be the same. That is because to remain the same, the memory must be recollected in the exact same way each time. — Metaphysician Undercover -

mcdoodle

1.1kI've read the interview, but it all seems to be a "back to Hume" moment. — Agustino

mcdoodle

1.1kI've read the interview, but it all seems to be a "back to Hume" moment. — Agustino

I am wary of this article. Take the remarks about colour,

In 1969, the anthropologists Brent Berlin and Paul Kay established that color names do not change the colors one sees, and later studies have confirmed this. — Manzotti

This is a scientific realist view of the situation and seems likely to be mistaken. Barbara Saunders has a trenchant critique of the Berlin/Kay view here. I am not clear if the rest of the Manzotti view is scientific-sounding assertion rather than based on good science. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

Oh sorry Augustino. I missed the whole interview. I read the first part, thought it was the end of the article, and lost interest. I'll read the rest and get back to you. -

Agustino

11.2k

Agustino

11.2k

Can you please cite the parts of the article you linked to which discredits the views of Manzotti?This is a scientific realist view of the situation and seems likely to be mistaken. Barbara Saunders has a trenchant critique of the Berlin/Kay view here. — mcdoodle

color names do not change the colors one sees — Manzotti

Also take a look at this. It seems that people can still perceive colors, even when they group them differently. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kAfter reading through the interview, I would say that my original criticism still holds. Manzotti does not adequately distinguish between past and future, memory and anticipation. So he speaks about mental activity as "rearranging causal relations with past events". Memories of external objects are past events, but we still must account for the act of "rearranging", and this is the creative act which is driven by anticipation. Anticipation cannot be validated by external objects because it's object is non-existent, and so this mental act, the creative act of rearranging, also cannot be described in reference to external objects. And so Manzotti continues to speak about rearranging, and juggling, and learning, without accounting for the agent of this act. He answers this with ambiguity "I am nothing", or "I am part of everything". But the problem is that his position requires an agent, and this brings us right back to the internal. There is an internal agent which is doing the rearranging, the creating. So it isn't really an externalist position at all.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kAfter reading through the interview, I would say that my original criticism still holds. Manzotti does not adequately distinguish between past and future, memory and anticipation. So he speaks about mental activity as "rearranging causal relations with past events". Memories of external objects are past events, but we still must account for the act of "rearranging", and this is the creative act which is driven by anticipation. Anticipation cannot be validated by external objects because it's object is non-existent, and so this mental act, the creative act of rearranging, also cannot be described in reference to external objects. And so Manzotti continues to speak about rearranging, and juggling, and learning, without accounting for the agent of this act. He answers this with ambiguity "I am nothing", or "I am part of everything". But the problem is that his position requires an agent, and this brings us right back to the internal. There is an internal agent which is doing the rearranging, the creating. So it isn't really an externalist position at all.

No, the mind is a no-thing as far as I'm concerned. What is "mind"? Until it's clarified what that even means, you're saying nonsense by the "mind" creates. — Agustino

Very clearly there has to be something which anticipates the non-existent states of the future, something which does the rearranging, which does the juggling, which does the learning. If you don't like the word "mind", then use "soul", or "agent", but the brain cannot completely account for this creativity because the brain is just another object. And that object only has past memories, and past memories cannot account for the anticipation of non-existent objects of the future.

Yes, so this constant conjunction isn't always the same. There must be an input from the imagination to fill in gaps of vagueness. — Agustino

So the input, from the imagination, and this is the creative factor, cannot be accounted for by the memories of past occurrences. It must be accounted for by reference to the anticipation of future occurrences. How can you account for the brain "representing" something which has not yet occurred? And this is what prediction is. -

Agustino

11.2k

Agustino

11.2k

What's there to distinguish? And why is this relevant?Manzotti does not adequately distinguish between past and future, memory and anticipation. — Metaphysician Undercover

What do you mean by "rearranging" and why would this be driven by anticipation?Memories of external objects are past events, but we still must account for the act of "rearranging", and this is the creative act which is driven by anticipation. — Metaphysician Undercover

Yes, you're right, it's not externalist. It collapses the distinction between external and internal.Anticipation cannot be validated by external objects because it's object is non-existent, and so this mental act, the creative act of rearranging, also cannot be described in reference to external objects. And so Manzotti continues to speak about rearranging, and juggling, and learning, without accounting for the agent of this act. He answers this with ambiguity "I am nothing", or "I am part of everything". But the problem is that his position requires an agent, and this brings us right back to the internal. There is an internal agent which is doing the rearranging, the creating. So it isn't really an externalist position at all. — Metaphysician Undercover

Why is an agent needed? All that is there is the change from one impression to the next (or likewise from one idea to the next), why is there an agent needed to do the changing? Why can't the changing itself be basic?And so Manzotti continues to speak about rearranging, and juggling, and learning, without accounting for the agent of this act. — Metaphysician Undercover

I disagree. The whole point of the article, as I see it, is to strike at this distinction between inner and outer, internal and external. Nothing is internal or external, the distinction is false. All there exists is impressions and copies of impressions (ideas). What is external here? There is no external object to the impressions - the impressions themselves are the objects.Very clearly there has to be something which anticipates the non-existent states of the future, something which does the rearranging, which does the juggling, which does the learning. If you don't like the word "mind", then use "soul", or "agent", but the brain cannot completely account for this creativity because the brain is just another object. And that object only has past memories, and past memories cannot account for the anticipation of non-existent objects of the future. — Metaphysician Undercover

Simple. The mind assumes that the same associations it's seen in the past will continue into the future. So if it finds something that smells like pineapple, but cannot see it, for whatever reason, then it will expect it to be pineapple. Remember that pineapple, on this account, is just a bundle of different impressions, smell being just one of them. So when we say it will expect it to be pineapple, we simply mean that the experience of the smell of pineapple, will recall/cause vague experiences of the taste of pineapple, and all the other previous impressions associated with it.So the input, from the imagination, and this is the creative factor, cannot be accounted for by the memories of past occurrences. It must be accounted for by reference to the anticipation of future occurrences. How can you account for the brain "representing" something which has not yet occurred? And this is what prediction is. — Metaphysician Undercover

And when I say "the mind" above, that's just a way of talking. In reality, there would just be the association. -

Marty

224The point of the article was that "words" are actually physical sounds.

Marty

224The point of the article was that "words" are actually physical sounds.

Say if this was the case, if words were like sign-posts that had no meaning associated with them. Then it would require an infinite regress of interpretations. That is, if you postulate a symbol or sign, that needs to be interpreted by inner-meaning, interpretation requires a interpreter. A interpreter's interpretation itself is subject to this issue of connection. This much is in Wittgenstein. -

Agustino

11.2k

Agustino

11.2k

They do have meaning associated with them. Hearing a certain combination of sounds (impression 1) evokes another set of impressions (however vaguely) which in the past were associated with it. So hearing the word "apple" invokes the impressions of an actual apple. There is no infinite regress and no problem.Say if this was the case, if words were like sign-posts that had no meaning associated with them. — Marty -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kWhat's there to distinguish? And why is this relevant? — Agustino

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kWhat's there to distinguish? And why is this relevant? — Agustino

It's relevant because of Manzotti's claim that mental activity is a rearranging of past things. But it is clear that in the mind there is future things as well as past things. So mental activity cannot be strictly a rearranging of past events, it also relates the past events to future events. So if he wants to discuss the rearranging of past things he needs to provide a means of separating past from future, such that he is discussing only past things, not past things in their relation to future things..

What do you mean by "rearranging" and why would this be driven by anticipation? — Agustino

"Rearranging" is Manizotti's word. And in his example of imagining furniture in a future home, this rearrangement is driven by anticipation. Also. when he uses "juggling" and "learning", these are both activities which are driven by anticipation of the future.

Yes, you're right, it's not externalist. It collapses the distinction between external and internal. — Agustino

No it clearly doesn't collapse that distinction, it makes it more evident, because the way he describes things implies a distinction between the internal agent which is carrying out these activities such as rearranging, juggling, and learning, and the things, the objects which form the past memories which the agent is engaged with in these activities.

Why is an agent needed? All that is there is the change from one impression to the next (or likewise from one idea to the next), why is there an agent needed to do the changing? Why can't the changing itself be basic? — Agustino

An agent is implied by Manizotti's description. Can you imagine rearranging, juggling, or learning, being carried out without an agent which is carrying out this activity?

I disagree. The whole point of the article, as I see it, is to strike at this distinction between inner and outer, internal and external. Nothing is internal or external, the distinction is false. All there exists is impressions and copies of impressions (ideas). What is external here? There is no external object to the impressions - the impressions themselves are the objects. — Agustino

If that is Manizotti's aim, then he clearly fails. He refers to words as well as other objects as "external objects". I think it's your turn to reread the interview.

Simple. The mind assumes that the same associations it's seen in the past will continue into the future. — Agustino

And you criticized me for using the word "mind", saying that it is "no-thing" and a term that needs clarification. You didn't allow me to say that the mind "creates" something, but now you've turned around to say that the mind "assumes" something. What's the difference between creating something and assuming something?

We're talking about how mental activity turns past memories toward the future events. If your claim is that this is done through the means of assumptions, then we must account for where these assumptions come from. As I said already, I believe the mind creates them. Where do you think they come from?

So if it finds something that smells like pineapple, but cannot see it, for whatever reason, then it will expect it to be pineapple. Remember that pineapple, on this account, is just a bundle of different impressions, smell being just one of them. So when we say it will expect it to be pineapple, we simply mean that the experience of the smell of pineapple, will recall/cause vague experiences of the taste of pineapple, and all the other previous impressions associated with it. — Agustino

See, you explain expectation through assumption. If it smells and looks like a pineapple one "assumes" that it will taste like a pineapple. But this is not really an assumption at all, it is a conclusion of inductive reasoning. Now we have to account for the mental performance which is inductive reasoning. This is to produce a generality from particular instances. A generality cannot be described as "a bundle of different impressions",. This would be a category mistake. A conclusion, a principle, which the agent can act on, in the future, is produced from the bundle of impressions. So there is a process of reduction whereby a bundle of impressions is reduced to a single (general) principle. Isn't this what we call abstraction? -

Agustino

11.2k

Agustino

11.2k

Yes, that is true.It's relevant because of Manzotti's claim that mental activity is a rearranging of past things. — Metaphysician Undercover

That's not clear at all to me. How are there future things in the mind?But it is clear that in the mind there is future things as well as past things. — Metaphysician Undercover

How is it driven by anticipation? He's imagining possible combinations, has nothing to do with the future as such. His purpose for imagining those possible combinations may be because he wants to see what ways there are to arrange his future house, but there's no necessary tie to the future in simply imagining possible combinations.And in his example of imagining furniture in a future home, this rearrangement is driven by anticipation. — Metaphysician Undercover

How?Also. when he uses "juggling" and "learning", these are both activities which are driven by anticipation of the future. — Metaphysician Undercover

No, you don't get the gist of his enterprise at all. Here's another interview:No it clearly doesn't collapse that distinction, it makes it more evident, because the way he describes things implies a distinction between the internal agent which is carrying out these activities such as rearranging, juggling, and learning, and the things, the objects which form the past memories which the agent is engaged with in these activities. — Metaphysician Undercover

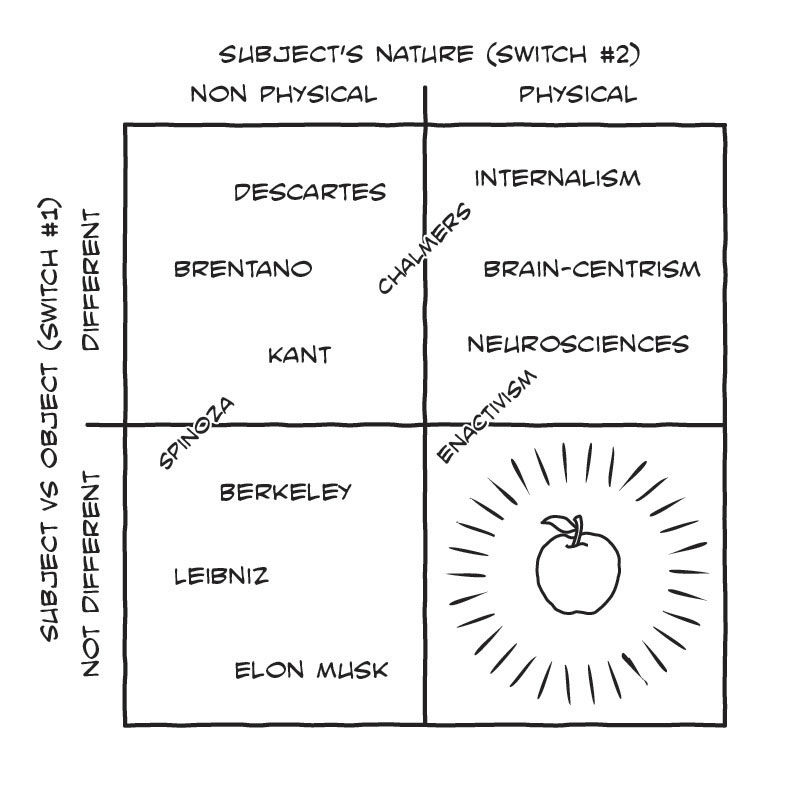

Manzotti: The enactivists toy with the first switch, without actually turning it all the way to not separate. They see that consciousness can’t be reduced to a property of the goings-on in the brain, so they start to look outside. But instead of considering the external object as such, they look at our dealings with the object, our handling the object, our manipulating the object, believing that consciousness is a product of the actions we perform. At the end of the day, though, the object remains doggedly separate from the subject who experiences it. And unfortunately, as we said last time, actions, whether they be eye movements, or touch, or chewing, are no better than neural firings when it comes to accounting for experience. How can my actions explain why the sky is blue or sugar sweet?

Parks: Okay, let’s stop playing with that switch and set it determinedly on subject and object not separate. As for the second switch, let’s again start with a subject that is not physical, since I suspect you are going to give that position short shrift.

Manzotti: Yes. This is the territory of Bishop Berkeley and Leibniz in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Crudely speaking, they proposed that subject and object become identical, the same thing, but both in a completely non-physical world.

His position is in the right-hand bottom corner. But I would push it even further, and argue that even the physical/non-physical distinction makes no sense.

So there is no internal agent at all carrying out the actions. The actions themselves are the agent. Why do we need an agent who is different from the actions themselves?

Yes, I can imagine rearranging, juggling, and learning happening by themselves, without an agent.An agent is implied by Manizotti's description. Can you imagine rearranging, juggling, or learning, being carried out without an agent which is carrying out this activity? — Metaphysician Undercover

I did read it carefully. He refers to it as "external objects" the same way I referred to it as "mind" when you objected in the next paragraph, or when we say "the sun goes down" (of course in truth we know it doesn't really go down, it's just a manner of speaking).If that is Manizotti's aim, then he clearly fails. He refers to words as well as other objects as "external objects". I think it's your turn to reread the interview. — Metaphysician Undercover

I already addressed this:And you criticized me for using the word "mind", saying that it is "no-thing" and a term that needs clarification. You didn't allow me to say that the mind "creates" something, but now you've turned around to say that the mind "assumes" something. What's the difference between creating something and assuming something? — Metaphysician Undercover

And when I say "the mind" above, that's just a way of talking. In reality, there would just be the association. — Agustino

No, my claim is that there is no projection towards the future, just old ideas coming to mind when new impressions are encountered through old associations.We're talking about how mental activity turns past memories toward the future events. If your claim is that this is done through the means of assumptions, then we must account for where these assumptions come from. As I said already, I believe the mind creates them. Where do you think they come from? — Metaphysician Undercover

They are triggered by new impressions. New impressions are similar to old impressions, so they trigger the very same conjunction of ideas that previous impressions triggered.Where do you think they come from? — Metaphysician Undercover

No, there is no question of assumption. One just experiences the vague impression (ie idea) of the taste of pineapple upon seeing another impression closely associated with it.If it smells and looks like a pineapple one "assumes" that it will taste like a pineapple. — Metaphysician Undercover -

mcdoodle

1.1kCan you please cite the parts of the article you linked to which discredits the views of Manzotti? — Agustino

mcdoodle

1.1kCan you please cite the parts of the article you linked to which discredits the views of Manzotti? — Agustino

I think that Barbara Saunders raises legitimate philosophical and scientific doubts about Manzotti's remarks about colour, including a purported genealogy from Gladstone through Rivers, culminating in

In 1969, the anthropologists Brent Berlin and Paul Kay established that color names do not change the colors one sees, and later studies have confirmed this.{/quote]

I don't know what you mean by 'parts of the article'. The whole article opposes the evolutionary model behind the Berlin-Kay model. There are many other articles by Saunders propounding this view, I just cited the most easily accessible one, and there is other literature supporting her philosophical doubts. I don't think this 'discredits' Manzotti, but I certainly think his views on color are glib and should take alternative paradigms into account. — Manzotti -

Banno

30.6kFor example - individuation. Individuation - that we see experiences as individual, and separate from one another, that we can even make such distinctions as red, blue, etc. - we don't get this concept from any one experience, or any multitude of experiences. Instead, in order to have more than one experience in the first place, individuation already must be possible. — Agustino

Banno

30.6kFor example - individuation. Individuation - that we see experiences as individual, and separate from one another, that we can even make such distinctions as red, blue, etc. - we don't get this concept from any one experience, or any multitude of experiences. Instead, in order to have more than one experience in the first place, individuation already must be possible. — Agustino

This needs a lot of work.

For starters, red does not work well as an example of an individual. It's lots of different things.

But to cut through to the core, how is learning what red is different from learning how to use the word "red"?

I don't think it is. If there are those who think that there is something more to red than how we use the word 'red', set it forth. -

Banno

30.6kWords in the mind are representations of the physical things. — Metaphysician Undercover

Banno

30.6kWords in the mind are representations of the physical things. — Metaphysician Undercover

So red is represented by what physical things?

Your answers always reduce to "the red ones!"

I don't think that helps. -

Agustino

11.2k

Agustino

11.2k

Words are irrelevant, it's concepts that matter. So sure, learning what red is, is the same as learning how to use the concept of red. Learning how to use the word "red" on the other hand is not very significant in and of itself.But to cut through to the core, how is learning what red is different from learning how to use the word "red"? — Banno

How is it possible for the operating system to load itself? In order for that to be possible, certain things must already exist such as electricity.Bootstrapping. The operating system loads itself. — Banno -

charleton

1.2k

charleton

1.2k

You have a weird way of thinking.in order to have more than one experience in the first place, individuation already must be possible. — Agustino

We do not need a concept of individuation to have experience. Experience underlies all conceptualising.

Living things from bacteria, to trees, to elephants big or tiny all experience living. none of them show any evidence of having a concept of "individuality". -

charleton

1.2kThink about child psychology.

charleton

1.2kThink about child psychology.

From the womb in the first couple of years is where conceptualising starts to occur.

But experience predicates it all.

Why are you asking that?mpressions of red, yellow, hard, soft, sweet, sour, etc. Where amongst those impressions is there an impression of "individual"? — Agustino

Proprioception, is an innate sense with which we experience our own bodies.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum