-

Streetlight

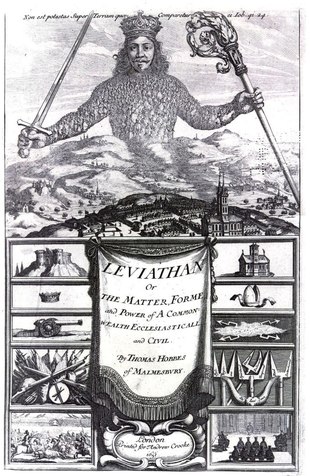

9.1kHobbes' famous frontispiece of The Leviathan looks like this:

Streetlight

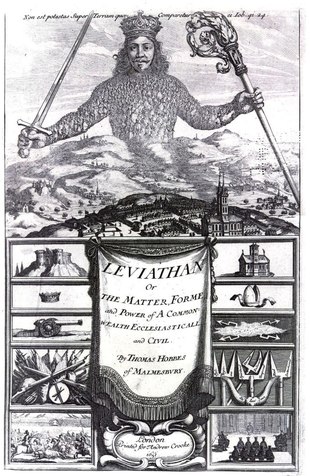

9.1kHobbes' famous frontispiece of The Leviathan looks like this:

Here is Agamben, from his book Stasis commenting on it:

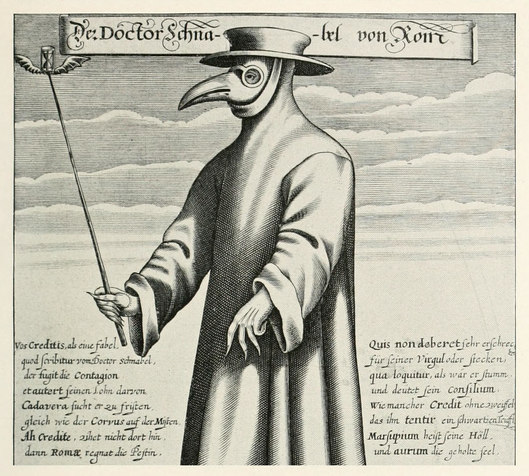

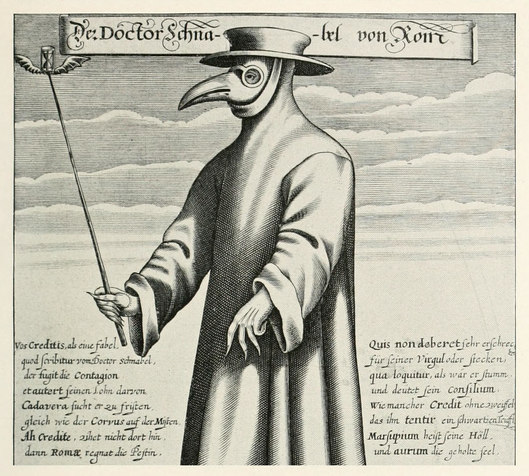

"We have evoked the curious presence, in the empty city, of the armed guards and of the two characters whose identity it is now time to reveal. Francesca Falk has drawn attention to the fact that the two figures standing near the cathedral are wearing the characteristic beaked mask of plague doctors. Horst Bredekamp had spotted the detail, but had not drawn any conclusions from it; Falk instead rightly stresses the political (or biopolitical) significance that the doctors acquired during an epidemic. Their presence in the emblem recalls ‘the selection and the exclusion, and the connection between epidemic, health and sovereignty’ (Falk 2011, 73).

Like the mass of plague victims, the unrepresentable multitude can be represented only through the guards who monitor its obedience and the doctors who treat it. It dwells in the city, but only as the object of the duties and concerns of those who exercise the sovereignty.

This is what Hobbes clearly affirms in chapter 13 of De Cive (and in chapter 30 of Leviathan), when, after having recalled that ‘all the duties of those who rule are comprised in this single maxim, “the safety of the people is the supreme law” [Salus populi suprema lex]’, he felt the need to specify that ‘by people we do not understand here a civil person, nor the city itself that governs, but the multitude of citizens who are governed [multitudo civium qui reguntur]’, and that by ‘safety’ we should understand not only ‘the simple preservation of life, but (to the extent that is possible) that of a happy life’ (Hobbes 1983, 13, 2–5: 195–6). While perfectly illustrating the paradoxical status of the Hobbesian multitude, the emblem of the frontispiece is also a courier that announces the biopolitical turn that sovereign power was preparing to make.

But there is another reason for the inclusion of the plague doctors in the frontispiece. In his translation of Thucydides, Hobbes had come across a passage in which the plague of Athens was defined as the origin of anomia (which he translates with ‘licentiousness’) and metabolē (which he renders with ‘revolution’):

'And the great licentiousness [anomia], which also in other kinds was used in the city, began at first from this disease. For that which a man before would dissemble, and not acknowledge to be done for voluptuousness, he durst now do freely: seeing before his eyes with such quick revolution, of the rich dying, and men worth nothing inheriting their estates'. (Hobbes 1843, 208)

Hence the notion that the dissoluta multitudo, which inhabits the city under the Leviathan’s dominion, may be compared to the mass of plague victims, who must be treated and governed. That the condition of the subjects of the Leviathan may be somehow comparable to that of the sick, is implied, moreover, in a passage from chapter 38 of Leviathan, in which Hobbes, glossing Isaiah 33: 24, writes that in the Kingdom of God the condition of the inhabitants is not being sick (‘The condition of the Saved, The Inhabitant shal not say: I am sick’ [Hobbes 1996, 317]) – almost as if, by contrast, the life of the multitude in the profane kingdom were necessarily exposed to the plague of dissolution."

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum