-

Banno

30.6kSeeing as how the man himself is to honour us, it may be time I came to grips with this issue. It also came up in 's recent thread, not to mention the distorted use to which the rules for constructing Aussie nicknames were put in the Shoutbox.

Banno

30.6kSeeing as how the man himself is to honour us, it may be time I came to grips with this issue. It also came up in 's recent thread, not to mention the distorted use to which the rules for constructing Aussie nicknames were put in the Shoutbox.

If i were to ask Chomsky a question, it would be "Are there analytic statements?"

But rather than just pose that question in the appropriate place, I'm looking for some discussion on the topic first. Lack of confidence on my part.

Those interested in the background and import of this issue might enjoy Analyticity and Chomskyan Linguistics, a supplementary entry in SEP to The Analytic/Synthetic Distinction.

I'll hopefully fill in a bit more as I work through the related material, but given the centrality of Analyticity to philosophical work, this seems worthy of a thread.

What do you think?

The question for Professor Chomsky is at https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/804011 -

RussellA

2.6k"Are there analytic statements?"

RussellA

2.6k"Are there analytic statements?"

In a performative act, I define X as x, y and z.

I tell at least one other person.

There is now a social community sharing the same language that knows that X means x,y and z.

The statement "X is z" is now an analytic statement and it is true that "X is z".

Provided that within a social community sharing the same language, at least one person has made a definition in a performative act, and told at least one other person, yes, analytic statements exist. -

Michael

16.8kIs there a difference between these two sentences?

Michael

16.8kIs there a difference between these two sentences?

1. A triangle is a 3-sided shape

2. "Triangle" means "3-sided shape"

Obviously there's a use-mention distinction, but is that distinction relevant here?

1) would be considered an analytic sentence but wouldn't 2) be considered a synthetic sentence? And I think a case could be made that 1) and 2) mean mostly the same thing. Would it then follow that 1) is synthetic and that 2) is analytic? Or perhaps that the analytic/synthetic distinction isn't a significant one?

Or if 2) is in fact an analytic sentence, is it not also a posteriori? Something Kant considered a contradiction? -

invicta

595Is there a difference between these two sentences?

invicta

595Is there a difference between these two sentences?

1. A triangle is a 3-sided shape

2. "Triangle" means "3-sided shape"

Obviously there's a use-mention distinction, but is that distinction relevant here? — Michael

In as far as I can see it apart from the use of quotation marks and the change of is to means, which is insignificant, the meaning does not change, the statement is essentially the same, and analytic. -

RussellA

2.6kObviously there's a use-mention distinction, but is that distinction relevant here? — Michael

RussellA

2.6kObviously there's a use-mention distinction, but is that distinction relevant here? — Michael

The problem is temporal.

Before the performative act, the combination of letters "the triangle" has no meaning.

As "the triangle" doesn't refer to anything, it has no use.

As "the triangle " doesn't exist in the common language, there cannot be any mention of it.

As "the triangle" doesn't exist in the common language, it cannot play a role in any analytic or synthetic statement.

During the performative act, the combination of letters "the triangle" is christened as a word, or as Kripke said, baptised, to have the meaning of a shape with three sides.

After the performative act, within the social community sharing a common language, the word "the triangle" means "a shape with three sides", and the statement "the triangle has three sides" is true.

As "the triangle" does now refer to something, ie, a shape with three sides, it has a use.

As the word "triangle" is now part of the common language, it can be mentioned as being a word within the common language.

As the word "the triangle" does now exist in the common language, it can play a role in analytic and synthetic statements. The statement "triangles have three sides " is analytic, as this is part of the definition of triangles. The statement "the triangle is orange" is synthetic, as this is not part of the definition of triangles.

There is no a priori knowledge of "the triangle" until it has been baptised in a performative act. There is only a posteriori knowledge of the word "the triangle" after it has been baptised in a performative act. -

Philosophim

3.5kThe careful difference is that the statement, "A triangle is a three sided shape" does not mean such a thing actually exists apart from our own definitions or imaginations. It is a blueprint and nothing more. Many of the mistakes in epistemology come from thinking that because we can define a word, it somehow makes it real apart from the definition we created.

Philosophim

3.5kThe careful difference is that the statement, "A triangle is a three sided shape" does not mean such a thing actually exists apart from our own definitions or imaginations. It is a blueprint and nothing more. Many of the mistakes in epistemology come from thinking that because we can define a word, it somehow makes it real apart from the definition we created. -

schopenhauer1

11kThere is no a priori knowledge of "the triangle" until it has been baptised in a performative act. There is only a posteriori knowledge of the word "the triangle" after it has been baptised in a performative act. — RussellA

schopenhauer1

11kThere is no a priori knowledge of "the triangle" until it has been baptised in a performative act. There is only a posteriori knowledge of the word "the triangle" after it has been baptised in a performative act. — RussellA

I think Chomsky (or at least some nativists) might argue that the very ability of the performative act is some sort of innate language acquisition capability.

See here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merge_(linguistics)

Also here:

Minimalism is an approach developed with the goal of understanding the nature of language. It models a speaker's knowledge of language as a computational system with one basic operation, namely Merge. Merge combines expressions taken from the lexicon in a successive fashion to generate representations that characterize I-Language, understood to be the internalized intensional knowledge state that holds of individual speakers. By hypothesis, I-language — also called universal grammar — corresponds to the initial state of the human language faculty.

Minimalism is reductive in that it aims to identify which aspects of human language — as well the computational system that underlies it — are conceptually necessary. This is sometimes framed as questions relating to perfect design (Is the design of human language perfect?) and optimal computation (Is the computational system for human language optimal?)[2] According to Chomsky, a human natural language is not optimal when judged based on how it functions, since it often contains ambiguities, garden paths, etc. However, it may be optimal for interaction with the systems that are internal to the mind.[3]

Such questions are informed by a set of background assumptions, some of which date back to the earliest stages of generative grammar:[4]

Language is a form of cognition. There is a language faculty (FL) that interacts with other cognitive systems; this accounts for why humans acquire language.

Language is a computational system. The language faculty consists of a computational system (CHL) whose initial state (S0) contains invariant principles and parameters.

Language acquisition consists of acquiring a lexicon and fixing the parameter values of the target language.

Language generates an infinite set of expressions given as a sound-meaning pair (π, λ).

Syntactic computation interfaces with phonology: π corresponds to phonetic form (PF), the interface with the articulatory-perceptual (A-P) performance system, which includes articulatory speech production and acoustic speech perception.

Syntactic computation interfaces with semantics: λ corresponds to logical form (LF), the interface with the conceptual-intentional (C-I) performance system, which includes conceptual structure and intentionality.

Syntactic computations are fully interpreted at the relevant interface: (π, λ) are interpreted at the PF and LF interfaces as instructions to the A-P and C-I performance systems.

Some aspects of language are invariant. In particular, the computational system (i.e. syntax) and LF are invariant.

Some aspects of language show variation. In particular, variation reduces to Saussurean arbitrariness, parameters and the mapping to PF.

The theory of grammar meets the criterion of conceptual necessity; this is the Strong Minimalist Thesis introduced by Chomsky in (2001).[5] Consequently, language is an optimal association of sound with meaning; the language faculty satisfies only the interface conditions imposed by the A-P and C-I performance systems; PF and LF are the only linguistic levels. — Minimalist Program -

RussellA

2.6kI think Chomsky (or at least some nativists) might argue that the very ability of the performative act is some sort of innate language acquisition capability. — schopenhauer1

RussellA

2.6kI think Chomsky (or at least some nativists) might argue that the very ability of the performative act is some sort of innate language acquisition capability. — schopenhauer1

I agree. Whilst on the one hand there cannot be a priori knowledge of "the triangle" until it has been baptised in a performative act, on the other hand, there must be some innate, a priori knowledge of the importance of the concept of triangle, otherwise the language speaker wouldn't have considered it worthwhile naming.

As with "snow is white" is true IFF snow is white, the expression in inverted commas exists in language whilst the expression not in inverted commas exists in the world, there is a difference between "the triangle" which exists in language and the triangle which exists in the world.

It can be argued exactly where this world exists, in the mind or external to any mind. Wittgenstein in Tractatus avoided the question altogether.

Life has been evolving for about 3.7 billion years on Earth, and must be responsible for the physical structure of the human brain as it is today, ie, the hardware. What the brain is capable of doing, ie it software, can only be a function of its hardware, ie, the physical structure of the brain. It is clear that a kettle can only boil water, it cannot play music, ie, what a physical structure is able to do must be determined by its physical structure, What the brain is able to achieve, its thoughts, concepts and language cannot be outwith the physical structure that enables such thoughts, concepts and language.

The linguist Noam Chomsky and the evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould proposed the theory that language evolved as a result of other evolutionary processes, essentially making it a by-product of evolution and not a specific adaptation. The idea that language was a spandrel, a term coined by Gould, flew in the face of natural selection. In fact, Gould and Chomsky pose the theory that many human behaviours are spandrels. These various spandrels came about because of a process Darwin called "pre-adaptation," which is now known as exaptation. This is the idea that a species uses an adaptation for a purpose other than what it was initially meant for. One example is the theory that bird feathers were an adaptation for keeping the bird warm, and were only later used for flying. Chomsky and Gould hypothesize that language may have evolved simply because the physical structure of the brain evolved, or because cognitive structures that were used for things like tool making or rule learning were also good for complex communication. This falls in line with the theory that as our brains became larger, our cognitive functions increased.

As regards the immediate topic "Are there analytic statements?", as "the triangle" has been baptised in a performative act as meaning "a shape having three sides", the statement "the triangle has three sides" can only be analytic. Therefore, there are analytic statements. -

schopenhauer1

11kChomsky and Gould hypothesize that language may have evolved simply because the physical structure of the brain evolved, or because cognitive structures that were used for things like tool making or rule learning were also good for complex communication. This falls in line with the theory that as our brains became larger, our cognitive functions increased. — RussellA

schopenhauer1

11kChomsky and Gould hypothesize that language may have evolved simply because the physical structure of the brain evolved, or because cognitive structures that were used for things like tool making or rule learning were also good for complex communication. This falls in line with the theory that as our brains became larger, our cognitive functions increased. — RussellA

I find the part about the evolution of language fascinating, especially the speculation surrounding it. The FoxP2 gene, mirror neuron system, plasticity and memory, pre-frontal cortex, and subcortical connections can help us understand how language evolved. It is likely that language initially evolved through exaptation and was later co-opted for further adaptation in parts of the brain.

Regarding Chomsky's position, there are three main camps in the language acquisition debate. The fully nativist camp (Chomsky, Fodor) believes that language acquisition is almost entirely innate, with syntax and semantics generated without the need for social or cultural conventions. The fully conventional camp (Wittgenstein et al) believes that language acquisition is almost entirely conventional and arises from how it is used in a community of language users. The mix of both camp (Tomasello et al) believes that language acquisition has some innate aspects that need to be in place but heavily relies on social cues, particularly aspects like shared attention.

In terms of the synthetic and analytic distinction, my interpretation of Chomsky's view is that the innate language acquisition device of the brain can automatically compute analytic statements, which are true by definition. However, synthetic statements require environmental learning to produce, so while they may use the language rules generated by the LAD, it is not the LAD itself that produces them. I am not sure if this is completely accurate or if this view has changed over time. For example, I know that certain LAD components have been admitted to be no longer necessary for language generation. Now I believe, "merge" is the only function viewed as necessary. How this relates to evolving view of analytic and synthetic, I am not sure though.

References that are useful:

Tomasello's theory of social cooperative origins based much more on evolutionary and developmental psychology experiments: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=46IrwGZpDQ4

Chomsky's theory, based much more on "optimal interface" and internal mental thought than on cooperative origins: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y0DiRj5Bud8&t=349s

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/evidence-rebuts-chomsky-s-theory-of-language-learning/

https://amp.theguardian.com/science/head-quarters/2015/nov/05/roots-language-what-makes-us-different-animals

https://languagedebates.wordpress.com/2017/12/19/chomsky-or-tomasello-katie-oregan-tries-to-avoid-sitting-on-the-fence-in-the-language-learning-debate/ -

Banno

30.6kThanks for the Scientific American link. Nice summation.

Banno

30.6kThanks for the Scientific American link. Nice summation.

The issue is if a statement can be true in virtue of the meaning of the words alone. But we do not have a consensus on what the meaning of the words means. Given that Georges Rey thought it necessary to add an entire supplement on Chomsky's view to the SEP article and that the editors accepted this, it seems it is quite involved. More than just an unconscious calculation. Rey quotes Chomsky as suggesting that it is an issue for empirical analysis. Rey is noncommittal, suggesting that Chomsky vacillates, but perhaps Chomsky is undecided because of the absence of empirical data. -

schopenhauer1

11kRey quotes Chomsky as suggesting that it is an issue for empirical analysis. — Banno

schopenhauer1

11kRey quotes Chomsky as suggesting that it is an issue for empirical analysis. — Banno

What is your interpretation as to what "empirical analysis" entails here for understanding analyticity?

4 out of 5 men believe unmarried males are bachelors. The rest are just the cheaters :rofl:.

**Did I just do a polysemous? :chin:. To be a bachelor or to act like a bachelor. So I guess not. One is the thing, one is only like the thing. A bank on the river would be more like a polysemous. -

Antony Nickles

1.4k“It is clear, as Katz and Fodor have emphasized, that the meaning of a sentence is based on the meaning of its elementary parts and the manner of their combination. … [T]here are cases that suggest the need for an even more abstract notion of grammatical function and grammatical relation than any that has been developed so far, in any systematic way.” Chomsky, not sure where.

Antony Nickles

1.4k“It is clear, as Katz and Fodor have emphasized, that the meaning of a sentence is based on the meaning of its elementary parts and the manner of their combination. … [T]here are cases that suggest the need for an even more abstract notion of grammatical function and grammatical relation than any that has been developed so far, in any systematic way.” Chomsky, not sure where.

I’m not fully up to speed with Chomsky, but I take it he is claiming that our language is meaningful because we know how words work individually (as labels perhaps) and they function together by some human process that we just need to decipher systematically. We imagine we do this all the time when we try follow where someone is going with a new (unexpected) thought. I’ve seen it on this board a lot; people see words they know and take them at first glance, imagining their first impression of them together is something they can easily understand.

The picture is perfect (perhaps too so) if we wanted to be certain about what would be meant by what we said, or, say, if we wanted to know what we should do (what would be the right thing to do) before we did it.

But if we extend a concept (or speak across it) the projection is not made inteligible by our understanding the individual words and some internal structure they have (or external structure the world has). We won’t figure it out ahead of time by being clever, we carry a concept forward in continuing to talk amongst ourselves as we forge a new path ahead. We put ourselves out in front of our words (responsive to them) in moving past our ordinary practices. There is no certainty that you will, or even can, take up my words (support my acts); that’s why we have questions, denials, imagination, impasse, and madness. -

RussellA

2.6kIsn't this generally tautological? All unmarried men are bachelors is saying unmarried men are unmarried men. — Tom Storm

RussellA

2.6kIsn't this generally tautological? All unmarried men are bachelors is saying unmarried men are unmarried men. — Tom Storm

In the statement "bachelors are unmarried men", "bachelors" should be thought of as a definition rather than a description.

As a description "bachelors are unmarried men" is tautological, where "unmarried men" is a synonym for "bachelors".

But rather, "bachelor" should be thought of as a definition, where "bachelor" is the definition of "unmarried men".

For example, rather than say "I see a large building, typically of the medieval period, fortified against attack with thick walls, battlements, towers, and in many cases a moat", it is far more convenient just to say "I see a castle", where "castle" is the definition of a large building, typically of the medieval period, fortified against attack with thick walls, battlements, towers, and in many cases a moat.

Similarly, rather than say "I see an unmarried man", it is more convenient just to say "I see a bachelor".

If language only consisted of words that referred to simpler concepts: red, loud, circle, line, sweet, thick, etc, the number of words required to express complex concepts would be inconveniently excessive. Therefore, for convenience, definitions are used to group sets of words together. Without definitions, language would be unwieldy.

As "castle" is a definition, the statement "The castle has thick walls" is analytic. As "bachelor" is a definition, the statement "The bachelor is a man" is analytic. -

Michael

16.8kIsn't this generally tautological? All unmarried men are bachelors is saying unmarried men are unmarried men. — Tom Storm

Michael

16.8kIsn't this generally tautological? All unmarried men are bachelors is saying unmarried men are unmarried men. — Tom Storm

If "bachelor" means "unmarried man" then all bachelors are unmarried men.

"Bachelor" can mean "unmarried man", but it can also mean "man who has never been married" or "person with a first degree from a university" or "a young knight serving under another's banner".

The sentence "bachelors are unmarried men" doesn't specify which meaning of "bachelor" is being used, hence the need for the antecedent in the first sentence above. -

Tom Storm

10.8kThe sentence "bachelors are unmarried men" doesn't specify which meaning of "bachelor" is being used, hence the need for the antecedent in the first sentence above. — Michael

Tom Storm

10.8kThe sentence "bachelors are unmarried men" doesn't specify which meaning of "bachelor" is being used, hence the need for the antecedent in the first sentence above. — Michael

Fair.

As a description "bachelors are unmarried men" is tautological, where "unmarried men" is a synonym for "bachelors". — RussellA

Yep. Thanks. -

schopenhauer1

11k

schopenhauer1

11k

It’s just the fact that the definitions must be learned from convention in the first place. If a society has no marriage, it may have no concept of bachelor and thus has no word for “bachelor”. @RussellA appropriately referenced this idea at the beginning of this thread when he discussed the performative “christening” (Kripke’s idea), though I think Kripke’s set of words were limited to proper names and kinds, the distinction being words that are true in all possible worlds (proper names and scientific kinds) and ones that are not (most other words / ones where meaning is from convention and use).

I’m not sure that’s what Chomsky had in mind for “empirical evidence” though. -

RussellA

2.6kCan you explain Quine's objection to analyticity? — Banno

RussellA

2.6kCan you explain Quine's objection to analyticity? — Banno

Quine wanted to give a non-circular account of the distinction between analytic and synthetic sentences.

Circular in that the notion of analyticity is being used as an explanation for necessity and a prioricity, yet necessity and a prioiricity is being used as an explanation of analyticity.

It is often said that analytic truths are true by definition, but Quine pointed out that an analytic truth can only be turned into a logical truth by replacing synonym with synonym, which again leads into the problem of circularity. Synonymity between two expressions leads to analyticity, but synonymity between two expressions requires analyticity.

As Quine wrote:

“There are those who find it soothing to say that the analytic statements of the second class reduce to those of the first class, the logical truths, by definition: ‘bachelor’, for example, is defined as ‘unmarried man.’ . . . Who defined it thus, and when? Are we to appeal to the nearest dictionary ...? Clearly, this would be to put the cart before the horse. The lexicographer is an empirical scientist, whose business is the recording to antecedent facts; and if he glosses ‘bachelor’ as ‘unmarried man’ it is because of his belief that there is a relation of synonymy between those forms . . . prior to his own work.”

Quine asks "who defined it thus", and the answer is, in a Performative Act, carried out either by a public Institution, by the general users of a language or a combination of the two.

J. L. Austin in the 1950's gave the name performative utterances to situations where saying something was doing something, rather than simply reporting on or describing reality. The paradigmatic case here is speaking the words "I do".

Kripke in Naming and Necessity provided a rough outline of his causal theory of reference for names, promoting it as having more potential that Russell's Descriptive Theory of Names, whereby names are in fact disguised definite descriptions. Kripke argues that your use of a name is caused by the naming of a thing, for example, the parents of a newborn baby name it, pointing to the child and saying "we'll call her 'Jane'." Henceforth everyone calls her 'Jane'. This is referred to as Jane's dubbing, naming, or initial baptism.

From the SEP - The Analytic/Synthetic Distinction:

“Analytic” sentences, such as “Paediatricians are doctors,” have historically been characterized as ones that are true by virtue of the meanings of their words alone and/or can be known to be so solely by knowing those meanings.

We can consider two stages in linguistic meaning:

Stage one: words are given their meaning in performative acts

Stage two: once words have their meanings, some statements are known to be true just by knowing the meaning of their words, ie, as the SEP notes, analytic statements.

The Performative Act breaks Quine's problem of circularity. -

Banno

30.6kYour idea is that all analytic statements are the direct result of performative acts.

Banno

30.6kYour idea is that all analytic statements are the direct result of performative acts.

For plane figures, if the sum of the internal angles of a polygon is 180º, then the polygon has three sides.

This is true in virtue of the meanings of the terms involved. It appears to by analytic.

Nothing in this argument has a form like "I name this a such-and-such"

That is, this analytic statement does not seem to be the result of a performative act.

I conclude that not all analytic statements are the result of performative acts of naming.

My suspicion is that your account is based on considering only one type of analytic statement. -

Banno

30.6kWhat is your interpretation as to what "empirical analysis" entails here for understanding analyticity? — schopenhauer1

Banno

30.6kWhat is your interpretation as to what "empirical analysis" entails here for understanding analyticity? — schopenhauer1

I suspect that Chomsky may well have had something not unlike the thought experiments used by Quine in Word and object. So the question arrises as to how Chomsky could avoid the inscrutability of reference and hence the indeterminacy of translation.

Interesting. Where do "Gavagai", the inscrutability of reference and the indeterminacy of translation fit in this account? -

schopenhauer1

11kSo the question arrises as to how Chomsky could avoid the inscrutability of reference and hence the indeterminacy of translation. — Banno

schopenhauer1

11kSo the question arrises as to how Chomsky could avoid the inscrutability of reference and hence the indeterminacy of translation. — Banno

I think one criticism of his general tendency is to change the goal posts as to what the innate structures are and how innate they are. For example, I think the generative grammar project (universal grammar) became less specific overtime. Where you had various functions you now have one, merge (or recursion). This may play into the hedging..

So with that in mind, I do know that Chomsky had two kinds of "devices" at play in his theories. There was the syntactic (how words combine) and the semantic (how words mean). He can preserve the syntactic as being a device that is more fixed (the merge concept) whilst still declaring the semantic as more plastic (learn from language use in the environment). Thus, he might get on board with Kripkean-esque idea that words are "annointed" and then changed-over-time in a community. Thus I still stick with RussellA on how this might look as for how words get their definitions.

My own spin here is that non-proper names and non-scientific kinds aren't so much "annointed" in the same way scientists and parents dub names in a very specific instance, but rather there is some start somewhere and then moves forward.. Thus a tribe sees the practice of marriage and adapts it. They had a word for "wild and free" called "boople" and someone in the tribe said, "the ones who are not married are kind of boople" eh? And then the next use of it is, "look at that boople over there not attached to anyone." And then it becomes something like "All booples are unmarried males". -

Paine

3.2k

Paine

3.2k

I am not sure if this counts as 'hedging' in regard to what is innate or not but the following (written in the late 70's) suggests Chomsky is not putting the 'logic' of syntax as making or breaking the argument for a 'preexisting' structure in the way he opposed behaviorism, for example.

To be sure, someone who believes in a level of representation of the type proposed by Katz can reply: “In doing so, I propose a legitimate idealization. I assume, with Frege, that there exist semantic elements common to all languages, independent of everything except language and thought. In rejecting this idealization, you make the same mistake as those who confuse pragmatics with syntax.”

Certainly, this objection has some force. But I doubt that it will wholly withstand further reflection. Whenever concepts are examined with care, it seems that they involve beliefs about the real world. This idea is not new: Wittgenstein and Quine, among others, have emphasized that our use of concepts is set within a system of beliefs about lawful behavior of objects; similar ideas have been attributed to Leibniz. Thus, when we use the terms chair or table, we rely on beliefs concerning the objects to which we refer. We assume that they will not disappear suddenly, that they will fall when they are let go, and so on. These assumptions are not part of the meaning of chair, etc., but if the assumptions fail we might conclude that we were not referring to a chair, as we had thought. In studying semantics one must keep in mind the role of nonlinguistic systems of belief: we have our expectations about three dimensional space, about texture and sensation, about human behavior, inanimate objects, and so on. There are many mental organs in interaction. To repeat an observation of Wittgenstein’s, we would not know how to name an object if at one moment it looked like a chair, and a moment later disappeared, that is to say, if it does not obey the laws of nature. The question: “Is that a chair or not?” would not have an answer according to strictly linguistic criteria. Admittedly it is difficult to establish such conclusions. Too little is understood about cognitive systems and their interaction. Still, this approach seems reasonable to me; to give it some real content, it would be necessary to discover something comparable to a generative grammar in the domain of factual knowledge, which is no small task. My own speculation is that only a bare framework of semantic properties, altogether insufficient for characterizing what is ordinarily called “the meaning of a linguistic expression,” can be associated correctly with the idealization “language.” — Chomsky, Noam. On Language: Chomsky's Classic Works: Language and Responsibility and Reflections on Language (p. 152). -

schopenhauer1

11k

schopenhauer1

11k

Good quote. I'd have to read what he says before and after this to get full picture probably. However, it seems that he thinks that there are beliefs about the world that are necessary for concepts to form. I'm not sure what that means one way or another except that it looks that he doesn't think there is something akin to a "concept module" in the brain. However, I think he is still in favor of syntactic recursion being a specific module that is innate and necessary for language.

These debates seem odd to me because I don't see what the opposition is. It sounds like these things are debates to the extent at what is learned and what is automatically generated (or rather, automatically being computed in some sort of cognitive apparatus). I just think that is weird because even learning has a cognitive apparatus (long term potentiation and things such as this), so is it the kind of apparatus (complete and specialized versus generalized brain apparatus)? This is too vague for me to really take seriously. It would have to be mapped one-to-one to cognitive neuroscience results, or at the least provide some psychological experiments on concept formation in infants, children, and adults for it to have teeth. And of course, even with this, there are so many scientific papers that what is really THE theory and what is relevant gets lost in the noise.. What counts as significant answers to these questions even in scientific conclusions? Hundreds and thousands of papers each year, and what counts as getting a close consensus seems to be harder to decipher. It's not the same as a new element discovered, or understanding of particle interaction. -

RussellA

2.6kYour idea is that all analytic statements are the direct result of performative acts................My suspicion is that your account is based on considering only one type of analytic statement.. — Banno

RussellA

2.6kYour idea is that all analytic statements are the direct result of performative acts................My suspicion is that your account is based on considering only one type of analytic statement.. — Banno

Your example may be reworded as: "a triangle is a plane figure, a polygon, where the sum of the internal angles is 180 deg", thereby defining "a triangle".

This is a complex concept, so can be carried out in a straightforward Performative Act of Naming, where one word is defined as a set of other words. This is a purely linguistic process, not requiring any link from word to world, and not requiring any link from linguistic to extralinguistic.

Where do "Gavagai", the inscrutability of reference and the indeterminacy of translation fit in this account? — Banno

The gavagai problem may be solved by taking into account the fact that there are simple and complex concepts, and these must be treated differently. In language, first there is the naming of simple concepts, and only then can complex concepts be named, such as the complex concept "gavagai".

Simple concepts include things such as the colour red, a bitter taste, a straight line, etc, and complex concepts include things such as mountains, despair, houses, governments, etc.

For complex concepts, the "gavagai" may be named in a Performative Act of Naming, such that "a gavagai is a gregarious burrowing plant-eating mammal, with long ears, long hind legs, and a short tail". One word is linked to other words, the linguistic is linked with the linguistic, not the world. Misunderstanding and doubt are minimised in a relatively simple process. As "a gavagai" is defined as having long ears, the statement "a gavagai has long ears" is analytic.

For simple concepts, the process is more complicated. The problem is that of linking a word to something in the world, linking the linguistic with the extra-linguistic. For example the colour "orange" is something that is orange, where one word is linked with one thing in the world

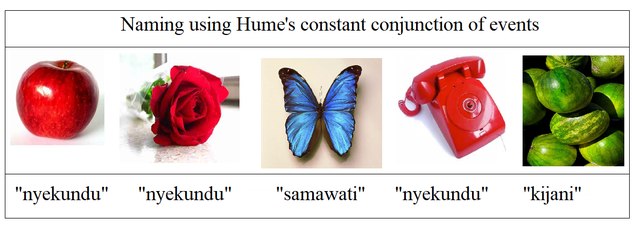

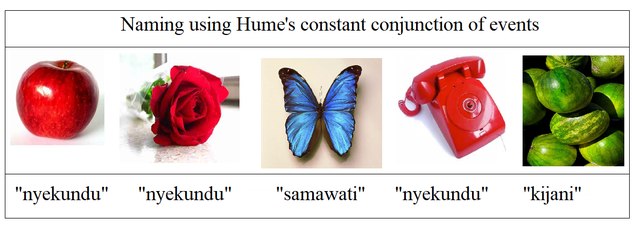

In order to explain the naming of simple concepts, I return to my diagram illustrating naming using Hume's constant conjunction of events, whereby learning a name is more an iterative process that is unlikely to be achieved at the first attempt. One needs to note that from the viewpoint of the observer, both the words and pictures are objects, things existing in the world, where the word is no less an object than the picture.

The words "nyekundu", "kijani" and "samawati" have been determined during Performative Acts of Naming either by an Institution or users of the language or a combination of both.

You asked before why the observer should necessarily link two objects that happen to be alongside each other. As the tortoise said to Achilles when playing chess, where is the rule that I have to follow the rules. Why should the observer take note of a constant conjunction of events? Because, as life has been evolving for about 3.7 billion years on Earth, taking note of a constant conjunction of events has been built into the structure of the brain as a mechanism necessary for survival, something innate and a priori.

Chomsky proposed that a person's ability to use language is innate. Taken from the https://englopedia.com article Innateness theory of language:

Linguistic nativism is a theory that people are born with the knowledge of a language: they acquire language not only through learning. Human language is complex and considered one of the most difficult areas of human cognition. However, despite the complexity of the language, children can accurately learn the language in a short period of time. Moreover, research has shown that language acquisition by children (including the blind and deaf) occurs at ordered developmental stages. This highlights the possibility that humans have an innate ability to acquire language. According to Noam Chomsky, “the speed and accuracy of vocabulary acquisition do not leave any real alternative to the conclusion that the child somehow possesses the concepts available before the language experience, and basically memorizes the labels for the concepts that are already part of him or her. conceptual apparatus “

In summary, first, complex concepts may be learnt as a set of simpler concepts in a Performative act of Naming, linking the linguistic to the linguistic. Second, simple concepts may be learnt by linking two objects in the world using Hume's constant conjunction of events, an innate ability having evolved over 3.7 billion years. The first object a name established during a Performative Act and the second object a picture, thereby linking the linguistic with the extralinguistic. -

schopenhauer1

11kThe first object a name established during a Performative Act and the second object a picture, thereby linking the linguistic with the extralinguistic. — RussellA

schopenhauer1

11kThe first object a name established during a Performative Act and the second object a picture, thereby linking the linguistic with the extralinguistic. — RussellA

Chomsky doesn’t seem to know if there is a conceptual apparatus so apparently that aspect isn’t part of his LAD? -

Paine

3.2k

Paine

3.2k

Thank you. I fully understand why you want to see the remarks in the context of his views as they changed over time.

These debates seem odd to me because I don't see what the opposition is. It sounds like these things are debates to the extent at what is learned and what is automatically generated (or rather, automatically being computed in some sort of cognitive apparatus). — schopenhauer1

I look at it through the lens of developmental psychology. The dynamic between the 'innate' and the environment points to neither aspect being the only process or ground of personal experience.

When Chomsky says: "Still, this approach seems reasonable to me; to give it some real content, it would be necessary to discover something comparable to a generative grammar in the domain of factual knowledge, which is no small task", that is asking for a science that goes beyond merely noting the dependence upon a repeatable experience of the world for the 'meaning' of propositions.

But it also goes beyond presuming a mechanism such as behaviorism does where different outcomes can be reduced to particular inputs. -

schopenhauer1

11kBut it also goes beyond presuming a mechanism such as behaviorism does where different outcomes can be reduced to particular inputs. — Paine

schopenhauer1

11kBut it also goes beyond presuming a mechanism such as behaviorism does where different outcomes can be reduced to particular inputs. — Paine

I think it’s simply unclear what’s being described. As I said “learning” is a vague notion and has its own cognitive and brain mechanisms. So it becomes learning vs a linguistic mechanism. But what learning is versus a linguistic mechanism isn’t spelled out there. “Is it a specific mechanism specialized for concepts or some other process” is what he’s getting at I guess. He doesn’t seem phased either way which indicates generative grammar and concept formation are separate domains and his theory only accounts for generative grammar. -

RussellA

2.6kChomsky doesn’t seem to know if there is a conceptual apparatus so apparently that aspect isn’t part of his LAD? — schopenhauer1

RussellA

2.6kChomsky doesn’t seem to know if there is a conceptual apparatus so apparently that aspect isn’t part of his LAD? — schopenhauer1

Being able to see the colour red and being able to see a link based on constant conjunction,

as inherent functions of the structure of the brain, and products of genetic coding, are possible without the need of conscious a priori concepts of red or constant conjunction. Concepts are subsequent to the event. -

schopenhauer1

11kBeing able to see the colour red and being able to see a link based on constant conjunction,

schopenhauer1

11kBeing able to see the colour red and being able to see a link based on constant conjunction,

as inherent functions of the structure of the brain, and products of genetic coding, are possible without the need of conscious a priori concepts of red or constant conjunction. Concepts are subsequent to the event. — RussellA

Yeah that makes sense, but I guess the argument is whether he thinks there is a definite specified structure for things as you describe (constant conjunction) in the brain, or some sort of general "learning". And that is where I am confused as to what he is saying or if that is indeed even the argument he is discussing in some of these passages about concepts.

One thing I am pretty sure he is saying is that concept formation is a separate issue than his generative grammar, and his LAD does not apply necessarily to a concept formation mechanism (e.g. something like a constant conjunction function).

A natural reaction might also be to question why he so easily separates these two. Being that concepts are important to language, perhaps the two things are intertwined inextricably and thus, a generative grammar mechanism by itself cannot exist, or needs to at least account for concept formation in the account of the generation of syntax and combinations of words into strings of coherency.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum