-

Richard B

579This is a position that I believe is refuted by our scientific understanding of the world and perception. Colour is "in the head", not in apples (or light). — Michael

Richard B

579This is a position that I believe is refuted by our scientific understanding of the world and perception. Colour is "in the head", not in apples (or light). — Michael

Let’s try a little thought experiment showing the relationship between language, experience, and science.

Individual A and B live in a world where there are two colors, red and blue. In their communities, when they were children, they learned the words “blue”, and “red” from the elders. The elder would point to a blue object and utter “blue”, and the same for a red object. After showing multiple different objects, some blue and some red, Individual A and B demonstrated to the community they were able to judge colors the same as their elders by using the words “red” and “blue” at the correct times.

On day a scientist comes along and wonders what is going on inside the brain when one sees red and blue. So, he decided to examine the brain by hooking up a test subject with electrodes to determine which neurons are “firing” when exposed to a blue object and a red object. Individual A decides to go first. The scientist finds an object that the community agrees is a blue object. Next, the scientist connects Individual A to the electrodes to measure Individual A’s neural response. Upon exposure of the blue object, neuron cluster 99 lights up in the brain. Individual A confirms to the scientist that they see a blue object by saying “blue”. Additionally, the scientist confirms the light reaching the subject is of the scientifically correct wavelength. The same routine is repeated with a red object, and this time neuron cluster 11 lights up in the brain. Individual A confirms to the scientist that they see a red object by saying “red”. Next, Individual B is connected to the electrodes. However, when Individual B is exposed to a blue object, neuron cluster 11 lights up in his brain. But Individual B still confirms that they see a blue object, by saying “blue”. Conversely, when exposed to a red object, neuron cluster 99 lights up. But Individual B still confirms that they see a red object by saying “red”.

Upon the completion of the experiment, an indirect realist walks in to see the results. They are not sure what to think. Surely, they thought that even though they are reporting the community accepted color word for each object correctly, they must be having different a “experience” of color since different neuron cluster are lighting up for each individual. Specifically, for A cluster 99 lights up when exposed to blue, but for B cluster 99 lights up for red. And, for B cluster 11 lights up for blue, but for A cluster 11 lights up for red. The indirect realist has no way of knowing which color individual A or B is having in any of these “private experiences” of color based on these results. But how could they ever make sense of these results since there is no private language we could use to understand anyway of what is going on inside their “heads.”

As Wittgenstein says in PI 293, “That is to say: if we construe the grammar of the expression of sensation on the model of ‘object and designation’ the object drops out of consideration as irrelevant.” -

Janus

18kNo. You can see five different colours there. That they are all shades of 'red' is something you were taught by the culture you grew up in. different cultures have different groupings and distinctions. — Isaac

Janus

18kNo. You can see five different colours there. That they are all shades of 'red' is something you were taught by the culture you grew up in. different cultures have different groupings and distinctions. — Isaac

This thesis is implausible; how could culture determine whether I or anyone else would class something as red or as purple or orange when it comes to edge cases?

It is rather the individual who determines whether someting counts as red or any other colour on the imprecise experiential basis of whether it looks red or looks orange or purple.

Of course I am not disputing the fact that the word 'red' is culturally acquired. -

Isaac

10.3kFirst person conclusions are what science is built on. As in every theory and hypothesis was someone's original individual first person conclusion or suspicion about reality that then was proven consistent for others too. — Benj96

Isaac

10.3kFirst person conclusions are what science is built on. As in every theory and hypothesis was someone's original individual first person conclusion or suspicion about reality that then was proven consistent for others too. — Benj96

True. The underlined bit being what's now happening.

They're both correct. Distinction can be at any stage from input, through processing or perception, to output or response.

The input (wavelengths) can be the same and the output can be different (reaching for colours words like green, red, brown or grey)

Or the input can be different and the response can be the same. Two people looking at two separate shades of yellow and saying yellow. — Benj96

Yes, but nowhere in there is this mysterious 'experience of red' that keeps being mentioned.

My experiences aren't self-evidence of gravity, but they are self-evidence of my experiences. That's common sense. — Michael

Ah!, well. If it's 'common sense' that settles it. To think... the amount of money my university has spent on research only to have wasted it all since you can just tell what's going on in your brain by having a bit of think about it... -

Isaac

10.3kThis thesis is implausible; how could culture determine whether I or anyone else would class something as red or as purple or orange when it comes to edge cases? — Janus

Isaac

10.3kThis thesis is implausible; how could culture determine whether I or anyone else would class something as red or as purple or orange when it comes to edge cases? — Janus

I know! Crazy isn't it!

That anyone might think a thing you can't personally understand could actually be the case! Implausible.... -

Michael

16.9kWe do something similar to the experiment I referenced before in my discussion with Issac, show individual A an object that he previously described as being blue, but have it fire neuron cluster 11 instead of 99 and ask him what colour the object is. If he says red then we know that the colour terms he uses refer to something that goes on in his head, not to something that goes on in the external world.

Michael

16.9kWe do something similar to the experiment I referenced before in my discussion with Issac, show individual A an object that he previously described as being blue, but have it fire neuron cluster 11 instead of 99 and ask him what colour the object is. If he says red then we know that the colour terms he uses refer to something that goes on in his head, not to something that goes on in the external world.

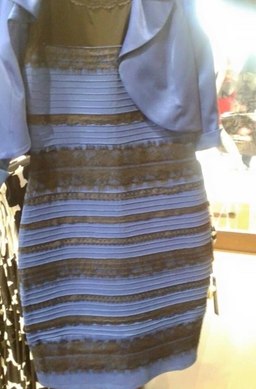

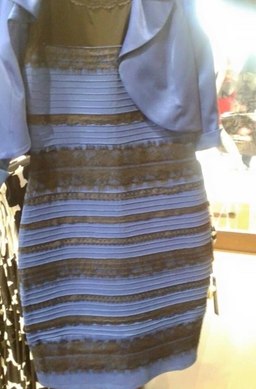

But, again, we don’t even need to consider anything so complicated. What colours do you see this dress to be? I recall a survey being done that showed that 2/3rds see it to be white and gold and 1/3 black and blue. How could I make sense of this and describe this if colour terms can’t refer to private experiences?

But as I’ve mentioned before, all this talk of language is a red herring. The fact remains that the dress appears differently to different people. The same stimulus triggers different, even conflicting, private experiences, and it is these private experiences that directly inform our understanding (hence why people use different words to describe that they see). That is clear evidence of indirect realism. -

RussellA

2.7kUpon the completion of the experiment, an indirect realist walks in to see the results. They are not sure what to think. Surely, they thought that even though they are reporting the community accepted color word for each object correctly, they must be having different a “experience” of color since different neuron cluster are lighting up for each individual...........The indirect realist has no way of knowing which color individual A or B is having in any of these “private experiences” of color based on these results. But how could they ever make sense of these results since there is no private language we could use to understand anyway of what is going on inside their “heads.” As Wittgenstein says in PI 293, “That is to say: if we construe the grammar of the expression of sensation on the model of ‘object and designation’ the object drops out of consideration as irrelevant.” — Richard B

RussellA

2.7kUpon the completion of the experiment, an indirect realist walks in to see the results. They are not sure what to think. Surely, they thought that even though they are reporting the community accepted color word for each object correctly, they must be having different a “experience” of color since different neuron cluster are lighting up for each individual...........The indirect realist has no way of knowing which color individual A or B is having in any of these “private experiences” of color based on these results. But how could they ever make sense of these results since there is no private language we could use to understand anyway of what is going on inside their “heads.” As Wittgenstein says in PI 293, “That is to say: if we construe the grammar of the expression of sensation on the model of ‘object and designation’ the object drops out of consideration as irrelevant.” — Richard B

Your post lays out my position as an Indirect Realist.

1) The Indirect Realist doesn't need a private language to have the private experience of a colour.

There are many things I see that I don't have a word for. This doesn't stop me from seeing them.

2) Wittgenstein's PI 293 is a good explanation why Indirect Realism is a workable theory.

PI 293 explains how there can be a public language even though each person's private experiences may be unknown to anyone else. -

Isaac

10.3kThe fact remains that the dress appears differently to different people. The same stimulus triggers different, even conflicting, private experiences, and it is these private experiences that directly inform our understanding (hence why people use different words to describe that they see). — Michael

Isaac

10.3kThe fact remains that the dress appears differently to different people. The same stimulus triggers different, even conflicting, private experiences, and it is these private experiences that directly inform our understanding (hence why people use different words to describe that they see). — Michael

This is not a fact, it's completely unsupported conjecture. Where is your evidence? -

unenlightened

10kThe same stimulus triggers different, even conflicting, private experiences, and it is these private experiences that directly inform our understanding (hence why people use different words to describe that they see). That is clear evidence of indirect realism. — Michael

unenlightened

10kThe same stimulus triggers different, even conflicting, private experiences, and it is these private experiences that directly inform our understanding (hence why people use different words to describe that they see). That is clear evidence of indirect realism. — Michael

The same experiment triggers conflicting conclusions. It is clear evidence of direct realism. The dress is a duck-rabbit. Everyone can see the same duck-rabbit dress, and that is indeed the assumption on which the experiment stands. If they didn't see the same thing, there would be nothing to explain. Because it is only an image, it can be ambiguous; if it were even a short movie, let alone a live encounter, the illusion could probably not be maintained, any more than anyone is deceived for long about ducks and rabbits, (or frogs and horses). One can mistake what one sees for something it is not, but this is no reason to deny that one sees it.

... -

RussellA

2.7kAnd as Wittgenstein pointed out in the first few pages of PI, you would thereby, already be participating in a language game, and so trying to explain meaning by making use of meaning. Then he cut to the chase: Stop looking for meaning, and instead look at use. — Banno

RussellA

2.7kAnd as Wittgenstein pointed out in the first few pages of PI, you would thereby, already be participating in a language game, and so trying to explain meaning by making use of meaning. Then he cut to the chase: Stop looking for meaning, and instead look at use. — Banno

There are two aspects: i) does a potential word have a use, ii) given a word has a use, what does the word mean.

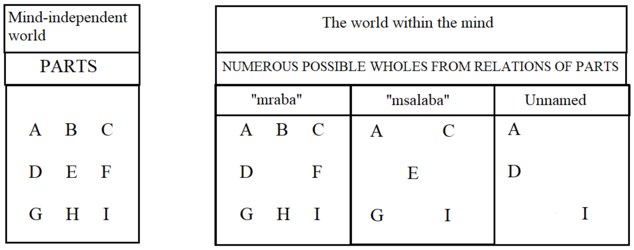

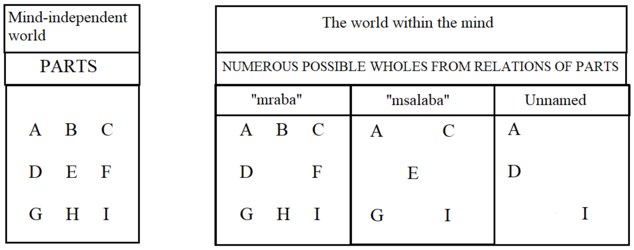

From my position of Neutral Monism, within a mind-independent world are elementary particles, elementary forces and space-time, and relations don't ontologically exist.

Does a potential word have a use

For the mind, some possible relations of the parts are useful within the language game and the broader life, and some aren't. For example the shapes "mraba" and "msalaba" are useful, but the shape with the parts ADI isn't. Only those shapes which are useful are named, and shapes which aren't useful are not named.

For example, the word "peffel", being part my pen and part the Eiffel Tower, has little use in either the language game or broader life, and cannot therefore be found in the dictionary.

Given a word has a use, what does the word mean

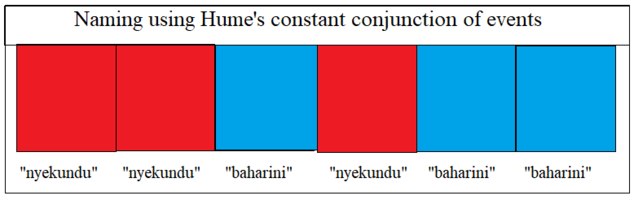

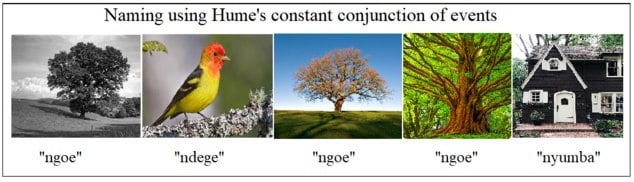

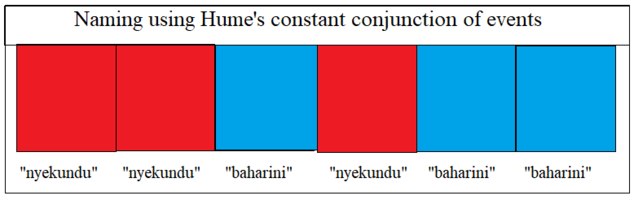

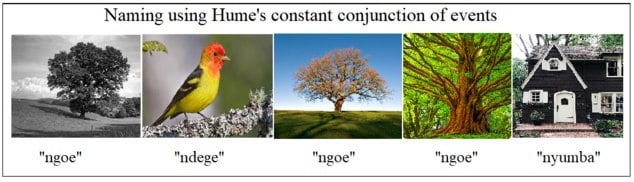

It is an undisputable fact that naming using Hume's constant conjunction of events works. It may not completely work first time as it is an iterative process, but it clearly works.

Given that the word "ngoe" has a use within the language game and broader life, what does "ngoe" mean. More broadly, what does "mean" mean.

Meaning is neither in the word "ngoe" or the picture of a ngoe, meaning is in the link between the word "ngoe" and the picture of a ngoe.

We cannot say that the word "ngoe" has a meaning, we cannot say that the picture of an ngoe has a meaning, but we can say that the link between the word "ngoe" and the picture of a ngoe has a meaning.

The link between the word and the picture is where the meaning resides. -

Michael

16.9kIf we assume that we do have eyes and brains, and that the mechanics of perception is as we currently understand it to be, then the explanation above shows indirect realism to be the case. — Michael

Michael

16.9kIf we assume that we do have eyes and brains, and that the mechanics of perception is as we currently understand it to be, then the explanation above shows indirect realism to be the case. — Michael

Interestingly, I've just discovered that Bertrand Russell made much the same argument in An Inquiry into Meaning and Truth.

Scientific scripture, in its most canonical form, is embodied in physics (including physiology). Physics assures us that the occurrences which we call ''perceiving objects'' are at the end of a long causal chain which starts from the objects, and are not likely to resemble the objects except, at best, in certain very abstract ways. We all start from "naive realism', i.e., the doctrine that things are what they seem. We think that grass is green, that stones are hard, and that snow is cold. But physics assures us that the greenness of grass, the hardness of stones, and the coldness of snow, are not the greenness, hardness, and coldness that we know in our own experience, but something very different. The observer, when he seems to himself to be observing a stone, is really, if physics is to be believed, observing the effects of the stone upon himself. Thus science seems to be at war with itself; when it most means to be objective, it finds itself plunged into subjectivity against its will. Naive realism leads to physics, and physics, if true, shows that naive realism is false. Therefore naive realism, if true, is false; therefore it is false. -

Michael

16.9kThis is not a fact, it's completely unsupported conjecture. Where is your evidence? — Isaac

Michael

16.9kThis is not a fact, it's completely unsupported conjecture. Where is your evidence? — Isaac

The fact that two people, fluent in English, describe the colours of the dress differently is evidence that the colours the dress appears to have to one are not the colours the dress appears to have to the other. -

Michael

16.9kThe same experiment triggers conflicting conclusions. It is clear evidence of direct realism. The dress is a duck-rabbit. Everyone can see the same duck-rabbit dress, and that is indeed the assumption on which the experiment stands. If they didn't see the same thing, there would be nothing to explain. Because it is only an image, it can be ambiguous; if it were even a short movie, let alone a live encounter, the illusion could probably not be maintained, any more than anyone is deceived for long about ducks and rabbits, (or frogs and horses). One can mistake what one sees for something it is not, but this is no reason to deny that one sees it. — unenlightened

Michael

16.9kThe same experiment triggers conflicting conclusions. It is clear evidence of direct realism. The dress is a duck-rabbit. Everyone can see the same duck-rabbit dress, and that is indeed the assumption on which the experiment stands. If they didn't see the same thing, there would be nothing to explain. Because it is only an image, it can be ambiguous; if it were even a short movie, let alone a live encounter, the illusion could probably not be maintained, any more than anyone is deceived for long about ducks and rabbits, (or frogs and horses). One can mistake what one sees for something it is not, but this is no reason to deny that one sees it. — unenlightened

I think you need to read this.

Indirect realism is a response to naive realism (what the author of the above paper calls "phenomenological direct realism"), not to what he calls semantic direct realism, which is in fact consistent with indirect realism, but for whatever reason uses direct realist language.

Indirect realists argue that the cold I feel isn't a mind-independent property of the Arctic air but a private experience caused by a particular temperature range. It's not the case that the polar bear who lives in the Arctic, but isn't cold, lacks the means to detect the cold in the air; it's just the case that he doesn't feel cold in such temperatures. Things like colour are no different in principle; they're just a different mode of experience (visual) caused by a different kind of stimulus (electromagnetic radiation). -

Isaac

10.3kThe fact that two people, fluent in English, describe the colours of the dress differently is evidence that the colours the dress appears to have to one are not the colours the dress appears to have to the other. — Michael

Isaac

10.3kThe fact that two people, fluent in English, describe the colours of the dress differently is evidence that the colours the dress appears to have to one are not the colours the dress appears to have to the other. — Michael

Again, all you're showing evidence of is responses.

Why is it, do you think, that when shown the actual dress in normal lighting conditions the overwhelming majority of people will see that it's blue and black. What explains that extraordinary convergence?

Direct realism has it like this...

Dress << Response

Indirect realism wants to introduce...

Dress << {representation} << Response

All you keep providing is evidence that people's responses are different. That has no bearing at all on the differences outlined above. People might respond differently to the same representation of a dress too. Different responses doesn't tell us anything about what it is people are responding to. -

Michael

16.9kAgain, all you're showing evidence of is responses. — Isaac

Michael

16.9kAgain, all you're showing evidence of is responses. — Isaac

Yes, and different private experiences are the best explanation for the different responses. I know that the reason I describe the colours of the dress to be white and gold is because it appears to me to be white and gold. My description comes after the fact, if I choose to describe what I see at all. It's not unreasonable to assume that this is the case for everyone else.

The fact that we can lie about what we see, or refuse to talk, is proof enough that there is a very real distinction between how the dress appears to us and our public description of how the dress appears to us. Of course, it's entirely possible that either everyone who describes the dress as black and blue is lying, or that everyone who describes the dress as white and gold is lying, but I don't think that a reasonable assumption at all. It is reasonable to assume that most people are being honest and that, like me, first the dress appears to have certain colours and then (if they choose) they describe the colours.

Why is it, do you think, that when shown the actual dress in normal lighting conditions the overwhelming majority of people will see that it's blue and black. What explains that extraordinary convergence? — Isaac

Because in normal lighting conditions objects which reflect a certain wavelength of light always appear to have a certain colour to me, and always appear to have a certain colour to you, and as children when shown such objects we are told that it is blue, and so we come to associate the word "blue" with the colour we see. Given the normal regularity between the wavelength of light and the apparent colour, there is normally a regularity in when we use the word "blue".

But then, in abnormal conditions, when an object which reflects a different wavelength of light nonetheless appears to be blue to me, but a different colour to you, I use the word "blue" to describe the colour I see and you use a different word.

This explains how it is the case that a) colour terms refer to a thing's private appearance, that b) in normal conditions we usually use the same colour terms to describe what we see, and that c) we sometimes don’t use the same colour terms to describe what we see. It’s a parsimonious explanation that’s consistent with the empirical evidence. -

Isaac

10.3kYes, and different private experiences are the best explanation for the different responses. — Michael

Isaac

10.3kYes, and different private experiences are the best explanation for the different responses. — Michael

I can see that it's your preferred explanation. I don't see any argument as to why it's the best. You seem to have introduced an element into the hypothesis which is not required. That's traditionally seen as a worse theory, not a better one.

It is reasonable to assume that most people are being honest and that, like me, first the dress appears to have certain colours and then (if they choose) they describe the colours. — Michael

It's not 'reasonable' at all. It don't understand from where you're getting this assumption that assuming the world to be the way you think it is is reasonable, but for others to disagree isn't.

I doesn't seem to me to be that way. I don't recognise this 'appearance' you claim is so obvious to you. So either;

a) I'm lying - in which case people do lie about their world views, in which case you may be too.

b) There's something wrong with my brain - in which case it's perfectly possible for brain to interact directly with the world, and so no reason to think indirect realism is necessary.

c) 'Private experiences' are built post hoc. You're convinced by your story, I'm more doubtful of mine.

You're talking to someone who disagrees with you about these 'private experiences' and yet are wanting to use their apparently self-evident nature as evidence. It's directly contradicted by the fact that I don't feel that way.

in normal lighting conditions objects which reflect a certain wavelength of light always appear to have a certain colour to me, and always appear to have a certain colour to you, and as children when shown such objects we are told that it is blue, and so we come to associate the word "blue" with the colour we see. — Michael

But you were arguing earlier that even language-less creatures see colours. Now you're saying the only reason we're the same is that we were taught the language. You're using our response again (saying 'blue') and then just inserting this other element (a colour experience) in between the actual light and our response to is without any need for it to be there. -

Michael

16.9kBut you were arguing earlier that even language-less creatures see colours. Now you're saying the only reason we're the same is that we were taught the language. You're using our response again (saying 'blue') and then just inserting this other element (a colour experience) in between the actual light and our response to is without any need for it to be there. — Isaac

Michael

16.9kBut you were arguing earlier that even language-less creatures see colours. Now you're saying the only reason we're the same is that we were taught the language. You're using our response again (saying 'blue') and then just inserting this other element (a colour experience) in between the actual light and our response to is without any need for it to be there. — Isaac

You asked me "Why is it .. that .. the overwhelming majority of people will see that it's blue and black."

What you mean by this is "why is it that the overwhelming majority use the words 'blue' and 'black'" to describe what they see".

And I explained that. We have learnt to use the words "blue" and "black" to describe objects that, upon closer examination, are found to reflect a certain wavelength of light.

My theory has the additional benefit of actually explaining why it is that we sometimes use different words to describe what we see, despite the shared external stimulus, i.e. light of a particular wavelength. Clearly something is going on in my head that isn't going on in your head that explains why you reach for one word and I reach for another. We can argue over whether this thing is some non-physical mental phenomena like "qualia" or simply physical brain activity, but we need to at least agree that something different is going on in our heads to explain the different descriptions.

It is certainly insufficient to argue that it is just the case that we use different words, and that there's no further explanation as to why this is.

It's not 'reasonable' at all. It don't understand from where you're getting this assumption that assuming the world to be the way you think it is is reasonable, but for others to disagree isn't. — Isaac

And I don’t understand how you think you can gaslight me into rejecting the reality of my first person experience. It is the foundational truth upon which all my other empirical knowledge rests.

If you were just trying to have me question the existence of other minds, and consider solipsism, then your arguments aren’t unfounded, but that seems to be for a different discussion. I think it fine to assume that solipsism isn’t the case when discussing direct and indirect realism.

At the very least, the indisputable (to me) reality of my first person experience is proof enough (to me) that me seeing red and me saying “I see red” are completely different things. I can see red things without saying so. I can lie about seeing red things. There are no rational (or empirical) grounds for me to deny this about myself.

b) There's something wrong with my brain - in which case it's perfectly possible for brain to interact directly with the world, and so no reason to think indirect realism is necessary. — Isaac

I don’t understand this conclusion. Given that your brain is inside your head and the apple is on the table in front of you, in what sense does the brain “interact directly” with the apple? There’s a whole lot of intermediate stuff in between, such as the air, light, your eyes, the nerves leading from your eyes to your brain, etc. Unless you want to stretch the meaning of "direct" into meaninglessness, in a very factual, physical sense, the brain does not interact directly with the outside world.

You're talking to someone who disagrees with you about these 'private experiences' and yet are wanting to use their apparently self-evident nature as evidence. It's directly contradicted by the fact that I don't feel that way. — Isaac

Then perhaps you are, in fact, a p-zombie, which would also explain your inability to make sense of p-zombies. Someone who doesn't have anything like first-person experience/qualia isn't going to understand the proposed distinction between something that has them and something that doesn't.

So at best you can argue that it's unreasonable of me to assume that other people are like me rather than like you. Maybe everyone else is like you, and I'm the only person in the world with first-person experience. But I think it unreasonable to assume that I'm unique. I think it more reasonable to assume that everyone else is much like me; that I'm an example of the typical human. Of the course the paradox is that you have to think the same, and assume that, like you, nobody has first-person experience.

Perhaps the more reasonable assumption is that everyone who denies the existence of first-person experience/qualia and the sensibility of p-zombies is a p-zombie, and the rest of us aren't. -

RussellA

2.7kDefining Direct Realism.

RussellA

2.7kDefining Direct Realism.

Some Direct Realists argue for Phenomenological Direct Realism (PDR), aka casual directness, a direct perception and a direct cognition of the object as it really is, and some argue for Semantic Direct Realism (SDR), aka cognitive directness, an indirect perception but direct cognition of the object as it really is.

The argument from illusion makes a strong case against PDR.

Supporters of SDR would argue that "Direct realism is where what we talk about is the tree, not the image of the tree or some other philosophical supposition."

However, it is equally true that "Indirect realism is where what we talk about is the tree, not the image of the tree or some other philosophical supposition."

As an Indirect Realist I directly see a tree, I don't see a model of a tree. Searle wrote "The experience of pain does not have pain as an object because the experience of pain is identical with the pain". Similarly, the experience of seeing a tree does not have a tree as an object because the experience of seeing a tree is identical with the tree.

Something else is needed to distinguish Semantic Direct Realism from Indirect Realism.

One could write:

Phenomenological Direct Realism (PDR) is a direct perception of the object "tree" as it really is in a mind-independent world

Semantic Direct Realism (SDR) is an indirect perception but direct cognition of the object "tree" as it really is in a mind-independent world

Indirect Realism is a direct perception and direct cognition of the object "tree" as it really is in the world existing in the mind, with the belief that although there is no "tree" in a mind-independent world, there is something in a mind-independent world that has caused such perception and cognition. -

Richard B

579The fact that two people, fluent in English, describe the colours of the dress differently is evidence that the colours the dress appears to have to one are not the colours the dress appears to have to the other. — Michael

Richard B

579The fact that two people, fluent in English, describe the colours of the dress differently is evidence that the colours the dress appears to have to one are not the colours the dress appears to have to the other. — Michael

Why is it, do you think, that when shown the actual dress in normal lighting conditions the overwhelming majority of people will see that it's blue and black. What explains that extraordinary convergence? — Isaac

es, and different private experiences are the best explanation for the different responses. — Michael

I set up the following experiment: I put a car in a garage. And ask a group of people, one at a time, please go into this garage, look at the car and let me know what color you think the car is when you come back out. After this experiment, I collect the results and find that different people are reporting the car has different colors.

The indirect realist may want to posit "sense data" as the explanation for the difference between people reporting different colors, and claim it the best explanation. Unfortunately, I would have to break the news to the indirect realist that this is an unnecessary explanation. The car was painted with a pigment called ChromaFlair. When the paint is applied, it changes color depending on the light source and viewing angle. In this example, this was intentionally done, and I am sure this can happen un-intentionally too.

At the very least, the indisputable (to me) reality of my first person experience is proof enough (to me) that me seeing red and me saying “I see red” are completely different things. — Michael

However, I think you would agree that you can't say to me that "I actually see a blue object when I say "I see red object." This make no sense. -

Michael

16.9kHowever, I think you would agree that you can't say to me that "I actually see a blue object when I say "I see red object." This make no sense. — Richard B

Michael

16.9kHowever, I think you would agree that you can't say to me that "I actually see a blue object when I say "I see red object." This make no sense. — Richard B

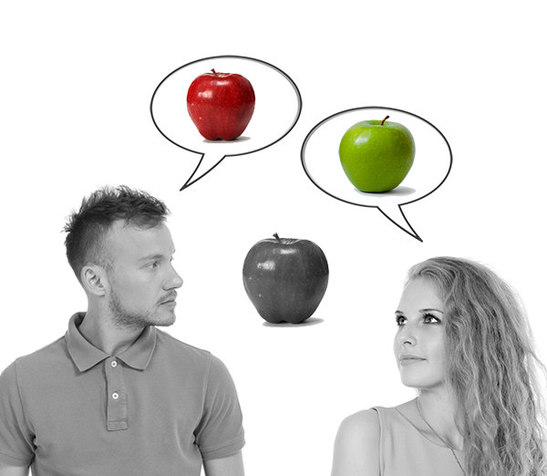

But it does make sense to say "what you mean by 'red' might not be what I mean by 'red'".

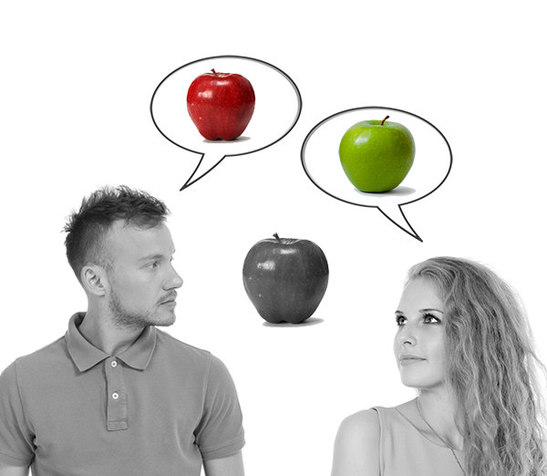

Referring back to this picture, if the man were able to see through the woman's eyes, he wouldn't say that the colour red looks different to this woman; he would say that the apple doesn't look red to the woman, it looks green.

Or at least that's what I'd say were I that man and able to see through the woman's eyes.

The indirect realist may want to posit "sense data" as the explanation for the difference between people reporting different colors, and claim it the best explanation. Unfortunately, I would have to break the news to the indirect realist that this is an unnecessary explanation. The car was painted with a pigment called ChromaFlair. When the paint is applied, it changes color depending on the light source and viewing angle. In this example, this was intentionally done, and I am sure this can happen un-intentionally too. — Richard B

But there are occasions where people see different colours despite nothing like this happening. Arguing that sometimes the differences can be explained with reference to the light source and viewing angle doesn't disprove that sometimes the differences must be explained with reference to something other than the light source and viewing angle.

The example of the dress is one such example that cannot be explained away the way you do here, as is the experiment I referred to before. -

Isaac

10.3kMy theory has the additional benefit of actually explaining why it is that we sometimes use different words to describe what we see, despite the shared external stimulus — Michael

Isaac

10.3kMy theory has the additional benefit of actually explaining why it is that we sometimes use different words to describe what we see, despite the shared external stimulus — Michael

We're sometimes wrong.

What exactly is missing in that theory such that a new theory is required which posits phenomena for which there is no other evidence?

We can argue over whether this thing is some non-physical mental phenomena like "qualia" or simply physical brain activity, but we need to at least agree that something different is going on in our heads to explain the different descriptions. — Michael

Yes, we can agree on that. In one case the path goes object>x>x>x>"blue" and in the other case object>x>x>x>"black". There is evidence for those Xs being different neural states and their outputs (different between people and between the same person at different times). There's no evidence that those Xs are some consistent 'experience of blue' that's unique to each person, it's just not there, and people have looked.

It is certainly insufficient to argue that it is just the case that we use different words, and that there's no further explanation as to why this is. — Michael

Indeed. There's all sorts of reasons why we might be mistaken.

And I don’t understand how you think you can gaslight me into rejecting the reality of my first person experience. It is the foundational truth upon which all my other empirical knowledge rests. — Michael

I'm not "gaslighting" you. You're arguing for the elf-evident existence of something I don't feel on the basis that you feel it. That's absurd... unless you do go down the solipsist route...

I can see red things without saying so. I can lie about seeing red things. There are no rational (or empirical) grounds for me to deny this about myself. — Michael

It's not about limiting your range of responses, it's about which response clarifies 'red'. You thinking of post-boxes might be a response to seeing red, but it doesn't clarify you colour response (you might have been reminded of the shape). You saying the word "red" is the one things which clarifies your response is to the object's light reflecting properties.

Given that your brain is inside your head and the apple is on the table in front of you, in what sense does the brain “interact directly” with the apple? — Michael

I just meant that there's no intermediate object, no 'representation' of an apple.

Then perhaps you are, in fact, a p-zombie, which would also explain your inability to make sense of p-zombies. Someone who doesn't have anything like first-person experience/qualia isn't going to understand the proposed distinction between something that has them and something that doesn't.

So at best you can argue that it's unreasonable of me to assume that other people are like me rather than like you. Maybe everyone else is like you, and I'm the only person in the world with first-person experience. — Michael

Yes. And accepting that possibility entails accepting that direct realism is possible. Which them means you'd have to explain why it is that you don't have it. Why has your brain evolved this convoluted system of intermediary representations when it's clearly not necessary to do so?

The example of the dress is one such example that cannot be explained away the way you do here. — Michael

The light source in the image is exactly the definition given for the dress discrepancy. The leading theory is that some people assume it is in daylight and so make a mental adjustment, others assume it is in orange, artificial light and so adjust that way. We don't go around assuming objects actually get darker whenever they pass into the shade, we adjust. -

RussellA

2.7kHow can the Direct Realist justify that the colours red and blue exist in a mind-independent world.

RussellA

2.7kHow can the Direct Realist justify that the colours red and blue exist in a mind-independent world.

The Direct Realist argues that they have direct cognition of the colours red and blue as they really are in a mind-independent world. meaning that the colours red and blue exist in a mind-independent world.

Red covers the range 625 to 750nm and blue the range 450 to 485nm.

In a mind-independent world, what determines that a wavelength of 650nm has something in common with a wavelength of 700nm, yet nothing in common with a wavelength of 475nm ? -

Michael

16.9kI just meant that there's no intermediate object, no 'representation' of an apple. — Isaac

Michael

16.9kI just meant that there's no intermediate object, no 'representation' of an apple. — Isaac

I’m not saying that either. I’m saying that the reality of colour perception is like this:

Or maybe even that both the man and the woman have the same kind of experience. The essential point is that the apple in between them isn’t coloured. It reflects a certain wavelength of light, but that’s all. Colour primitivism, which naive realists believe, is false.

And further, that when the man uses the term “grue” to describe the colour of the apple, he’s referring to what’s present in his experience and not present in the woman’s (in the particular example of that image), not to the fact that the apple reflects light with a wavelength of 450nm. -

Richard B

579Arguing that sometimes the differences can be explained with reference to the light source and viewing angle doesn't disprove that sometimes the differences must be explained with reference to something other than the light source and viewing angle. — Michael

Richard B

579Arguing that sometimes the differences can be explained with reference to the light source and viewing angle doesn't disprove that sometimes the differences must be explained with reference to something other than the light source and viewing angle. — Michael

But there is a difference between these two explanations, one metaphysical and one scientific. The scientific explanation has physical theory behind it. Verified countless times by a community of scientist. It has power to predict future occurrences and the power to construct our environment. All verifiable in the public realm.

The other, a metaphysical theory positing “sense data” which is in principle private, unaccessible, and with un-unverifiable claims. Lastly, as I have been arguing irrelevant to the meaning of the language used.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum