-

Michael

16.9kAnd also from close to the start of this discussion:

Michael

16.9kAnd also from close to the start of this discussion:

I suppose the latter is the implication of fallibilism. If knowledge does not require certainty then I can know everything even if I am not certain about anything. In this case I have fallible omniscience.

And I think certainty is only possible if the truth is necessary, so infallible omniscience requires that all truths are necessary. -

Michael

16.9kSo far as I can see your problems have been addressed successfully. — Banno

Michael

16.9kSo far as I can see your problems have been addressed successfully. — Banno

I don't think they have. I said this:

These two are true:

1. I believe that aliens exist

2. I might be wrong

One of these is true:

3. Aliens exist

4. Aliens do not exist

It is possible that these 3 are true:

1. I believe that aliens exist

2. I might be wrong

3. Aliens exist

If these three are true then I have a true belief that might be wrong.

@Srap Tasmaner's response was to say that if 3 is true then 2 is false, which entails via modus tollens that if I might be wrong then I am wrong. This is false. I believe that aliens exist but I might be wrong. It does not follow from this that aliens do not exist.

So answer me: can I be wrong? -

Michael

16.9k

Michael

16.9k

Either this is a valid argument:

1. I believe that aliens exist

2. I might be wrong

3. Therefore, aliens do not exist

Or it is possible that these three are all true:

1. I believe that aliens exist

2. I might be wrong

3. Aliens exist

If you believe that the first is a valid argument then I think yours is the belief in error. -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

"I might be wrong" here means, it is possible that aliens do not exist. That is, there is a possible world in which aliens do not exist.

If you add the further premise that aliens do exist in this world, you can draw two conclusions: (1) they are possible; (2) this is not one of the worlds in which they do not exist. That's it. If I suggested otherwise, I must have expressed myself poorly. -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

I should add: if you don't like my translation of (2), and would prefer it to be something like "It is possible there are no aliens here, in this world" then, in the presence of a further premise that there are or are not aliens here, this can only be understood as an epistemic possibility -- that is, as a way of saying I don't happen to know. -

Michael

16.9k"I might be wrong" here means, it is possible that aliens do not exist. That is, there is a possible world in which aliens do not exist. — Srap Tasmaner

Michael

16.9k"I might be wrong" here means, it is possible that aliens do not exist. That is, there is a possible world in which aliens do not exist. — Srap Tasmaner

Again, when I say "I might be wrong" I'm not saying "I'm actually right but there's a possible world where I'm wrong". I'm saying "I might actually be wrong". -

Michael

16.9kI should add: if you don't like my translation of (2), and would prefer it to be something like "It is possible there are no aliens here, in this world" then, in the presence of a further premise that there are or are not aliens here, this can only be understood as an epistemic possibility -- that is, as a way of saying I don't happen to know. — Srap Tasmaner

Michael

16.9kI should add: if you don't like my translation of (2), and would prefer it to be something like "It is possible there are no aliens here, in this world" then, in the presence of a further premise that there are or are not aliens here, this can only be understood as an epistemic possibility -- that is, as a way of saying I don't happen to know. — Srap Tasmaner

You can understand it as epistemic possibility if you like, but using the phrase "I don't happen to know" is misleading given that:

Either this is a valid argument:

1. I believe with justification that aliens exist

2. I might be wrong

3. Therefore, aliens do not exist

Or it is possible that these three are all true:

1. I believe with justification that aliens exist

2. I might be wrong

3. Aliens exist

If we accept that it is possible that all three are true then we accept that it is possible to have knowledge (a justified true belief, given by 1 and 3) that might be wrong (given by 2). -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

(2) breaks down into cases, right?

(2a) I'm not wrong, and aliens do exist here.

(2b) I am wrong, and aliens do not exist here.

Are both of those cases consistent with premise (3)?

No, they are not. By disjunctive inference, we are forced into the (2a) branch. -

Michael

16.9k(2) breaks down into cases, right?

Michael

16.9k(2) breaks down into cases, right?

(2a) I'm not wrong, and aliens do exist here.

(2b) I am wrong, and aliens do not exist here.

Are both of those cases consistent with premise (3)?

No, they are not. By disjunctive inference, we are forced into the (2a) branch. — Srap Tasmaner

Edit: I've tried to summarise my view below so you might not need to address this comment.

Are you saying that "I might be wrong" means "I'm not wrong"? That doesn't seem to be at all consistent with ordinary use or intention. And if it were the case then this would be a valid argument:

I believe with justification that aliens exist

I might be wrong

Therefore, aliens exist

Or are you saying that "I might be wrong" means "either I'm not wrong or I'm wrong"? That would be consistent with (3), and so my claim that we can have knowledge and might be wrong is true.

But is that all it means? You and others have repeatedly rejected the claim that we can have knowledge and might be wrong, and have said that if we're not wrong then we can't be wrong, and so clearly mean by "I might be wrong" something other than "either I'm not wrong or I'm wrong".

And I wonder if this is consistent with ordinary use and intention. Do these two mean the same thing?

I believe that aliens exist but I might be wrong

I believe that aliens exist and either I'm not wrong or I'm wrong -

universeness

6.3k"Possibly" in current math would be a conjecture. It would go nowhere logically by itself. "Believe" really would be nonsense in mathematics. — jgill

universeness

6.3k"Possibly" in current math would be a conjecture. It would go nowhere logically by itself. "Believe" really would be nonsense in mathematics. — jgill

:up: I also know of no attempts in the current AI developments where they are trying to emulate the human concept of belief. I do think that belief is strongly associated with fear, instinct and even intuition so I don't think computing science and artificial intelligence can completely ignore 'belief' if they wish to emulate human consciousness effectively but I see no place for fear, instinct, intuition or belief in mathematics. Mathematicians YES, absolutely, but mathematics, NO.

It's easy to 'model' human thought processes by substituting words like 'not,' 'and,' 'at least one example exists' with keyboard symbols such as ∧, ¬ etc. It's no more than a convenient text substitution system or 'shorthand.' It seems to me that there is nothing new in modal logic language that can tackle questions such as 'The Paradox of Omniscience.' -

Michael

16.9k@Srap Tasmaner

Michael

16.9k@Srap Tasmaner

I've tried to collect the entirety of my thoughts below. Perhaps you would clarify exactly which step you take issue with?

One of these is a valid argument, where knowledge is taken to be justified true belief:

Argument 1

I believe with justification that John is a bachelor

My belief might be wrong

Therefore, John is not a bachelor

Argument 2

I believe with justification that John is a bachelor

My belief might be wrong

John is a bachelor

Therefore, I have knowledge that might be wrong

If we accept that Argument 1 is invalid then how are we to interpret "might be wrong"? One interpretation is "is not certain", and so the argument is:

I believe with justification that John is a bachelor

My belief is not certain

John is a bachelor

Therefore, I have knowledge that is not certain

Another interpretation is "is possibly false", and so the argument is:

I believe with justification that John is a bachelor

My belief is possibly false

John is a bachelor

Therefore, I have knowledge that is possibly false

At this point it is important to understand that there is a distinction between "is false" and "is possibly false". "is possibly false" just means "is not necessarily true", and so the argument is:

I believe with justification that John is a bachelor

My belief is not necessarily true

John is a bachelor

Therefore, I have knowledge that is not necessarily true

In other words, I know that John is a bachelor and it is not necessarily true that John is a bachelor.

Nothing so far should be controversial (except to the extent that the fallibilism of the first interpretation is controversial).

However, there is some ambiguity with "is possibly false", as shown by the prima facie difference between these two claims:

a. There is a possible world where my belief is false

b. It is possible that my belief is actually false

If when I claim that my belief might be wrong I am making a claim such as (a) then the interpretation of "might be wrong" as "is not necessarily true" above is sufficient, but if I am making a claim such as (b) then something more must be said.

It may be tempting to simplify matters by saying that (b) is false if my belief is true, but then this argument would be valid:

I believe with justification that John is a bachelor

It is possible that my belief is actually false

Therefore, John is not a bachelor

If this is unacceptable then how are we to interpret (b)? Perhaps as the claim that there is a possible world where the actual world is one of the possible worlds where p? This second layer of possible world semantics is admittedly confusing. Is it coherent? If not then how are we to interpret (b)? Perhaps it is to be interpreted as "my belief is not certain" as explained above? -

Michael

16.9kThe paradox, then, is that:

Michael

16.9kThe paradox, then, is that:

1. "might be wrong" means either "is not certain" or "is not necessarily true"

2. It is acceptable to say that we can have knowledge that is not certain (if we're fallibilists)

3. It is acceptable to say that we can have knowledge that is not necessarily true

4. It is unacceptable to say that we can have knowledge that might be wrong

There is a contradiction.

A partial solution is to abandon fallibilism:

1. "might be wrong" means either "is not certain" or "is not necessarily true"

2. It is unacceptable to say that we can have knowledge that is not certain

3. It is acceptable to say that we can have knowledge that is not necessarily true

4. It is unacceptable to say that we can have knowledge that might be wrong

Although if, as my gut intuition suggests, certainty is only possible if the truth is necessary, we have a complete solution:

1. "might be wrong" means either "is not certain" or "is not necessarily true"

2. It is unacceptable to say that we can have knowledge that is not certain

3. It is unacceptable to say that we can have knowledge that is not necessarily true

4. It is unacceptable to say that we can have knowledge that might be wrong

But I think that if we wish to remain fallibilists then we must reject (4) and say that it is acceptable to say that we can have knowledge that might be wrong.

It may be tempting to find a third meaning of "might be wrong" that allows us remain fallibilists without rejecting (4), but such a meaning will then entail that this is valid:

I believe with justification that John is a bachelor

My belief might be wrong

Therefore, John is not a bachelor -

bongo fury

1.8k2. It is unacceptable to say that we can have knowledge that is not certain

bongo fury

1.8k2. It is unacceptable to say that we can have knowledge that is not certain

3. It is unacceptable to say that we can have knowledge that is not necessarily true — Michael

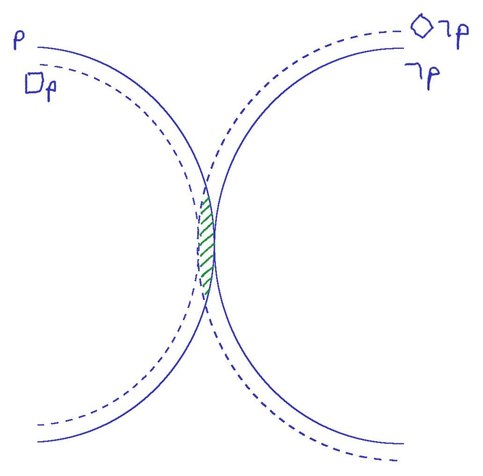

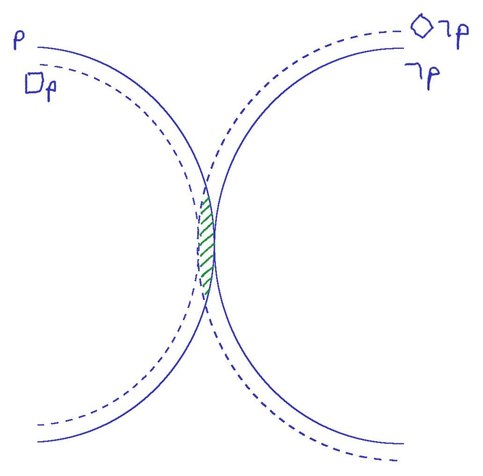

So K becomes a modal operator?

(Or might as well.)

E.g. Kp (or □p) meaning not even secretly not p (or ¬◇¬p).

By analogy with necessarily p meaning not even possibly not p.

Then omniscience is cool, because there are no secret errors. Green zone gone when all p are Kp (□p):

Just as you are observing that omniscience will be cool if there are no possible errors.

Either way, no error problem.

You might object: but my green zone doesn't really contain any errors. It isn't inside the not p circle. So my 'secret errors' (absent omniscience) are no such thing.

But that was my point about your 'possible' errors being unintuitive enough, already. Their being both p and possibly not p is sufficient grounds for worrying at length about relevant angles on "might be wrong". We don't need to assume that modal logic will solve the problem, though. Modality is the problem. -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

3. It is acceptable to say that we can have knowledge that is not necessarily true — Michael

The ambiguity here is crippling.

Let's say there need not be aliens, but there are. That they exist is a contingent fact, not necessary, and we can know this contingent fact.

- This is what (3) seems to say that most of us would agree with.

If you accept that Kp → p, then given Kp, you "must" conclude p, by modus ponens. That "must" is a sort of necessity, but it's logical necessity; it is different from the sort of necessity that the existence of aliens lacks. (Perhaps it would be more modern only to say that you may introduce p. In place of logical necessity, we would have logical permission or logical entitlement. In epistemic lands, that might be close to "warrant" or even "justification".)

If you define knowledge that p to include a stipulation that p is true, then it is analytic that when you know that p, p is true, and that's yet another sense of "necessity", very close to logical necessity, but perhaps different, as no specific logical principle is invoked.

- Something around here is what (3) seems to want to deny.

And of course, if you have P in hand, either as a premise, or derived, perhaps from your knowledge that P, then at that point we can apply the law of noncontradiction to deny that P is also false, and we'll usually say, P "cannot" be false, or that it cannot not be true, which is either a case of logical necessity, or the law of noncontradiction (perhaps also double negation) merely expressing the meaning of "true", "false", and "not", in which case this is analytic. Whatever.

- And this is the part of (3) I've been trying to make clear: once you have, perhaps even as a premise, that there are aliens, then there are, really and truly, here in the actual world, and it no longer makes sense to say maybe there aren't, even though their presence is entirely contingent. It still makes sense, as others have pointed out, to say, in English, "there might not have been", but that's not a temporal usage, that's the English past subjunctive, expressing contingency. We all agree, in some cases, that what is might not have been, but none of us agree, for any case, that what is might not be.

-

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

This entire thread has been devoted to confusing "I have knowledge of something that need not be the case" with "I have knowledge of something that may not be the case." -

Michael

16.9kThis entire thread has been devoted to confusing "I have knowledge of something that need not be the case" with "I have knowledge of something that may not be the case." — Srap Tasmaner

Michael

16.9kThis entire thread has been devoted to confusing "I have knowledge of something that need not be the case" with "I have knowledge of something that may not be the case." — Srap Tasmaner

(sorry, deleted the previous comment)

I think our conflict is in regards to the prima facie difference between saying:

a. There is a possible world where my belief is false

b. It is possible that my belief is actually false

Given Kp ∧ ◇¬p I trust that you accept (a) is true even if my belief is true?

But I suspect that you claim that (b) is false if my belief is true? -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

No one raises an eyebrow on hearing "I think there are three left, but I could be wrong," or "I'm pretty sure there are three left, but I could be wrong," or even "I'm almost certain there are three left, but I could be wrong."

But no one ever says "I know for a fact there are three left, but I could be wrong."

Why not? -

Michael

16.9kBut no one ever says "I know for a fact there are three left, but I could be wrong."

Michael

16.9kBut no one ever says "I know for a fact there are three left, but I could be wrong."

Why not? — Srap Tasmaner

I suspect because of what I said here:

I think the reason that this conclusion seems counterintuitive is that even if we claim to be fallibilists there is this intuitive sense that knowledge entails certainty.

But even though we don't say it, I think that this argument shows that such a claim would be true:

1. I believe with justification that John is a bachelor

2. My belief might be wrong

3. John is a bachelor

4. Therefore, my true (from 3) justified belief (from 1) might be wrong (from 2)

The issue, then, is to unpack what "might be wrong" means, which I have tried to do above.

I don't understand how you can deny the conclusion. Maybe you're equivocating and so mean something different by the "might be wrong" in "my belief might be wrong" to the "might be wrong" in "my true justified belief might be wrong"?

Unless you think, as you seemed to before, that this is valid:

I believe with justification that John is a bachelor

My belief might be wrong

Therefore, John is not a bachelor -

Isaac

10.3kthere is a possible world in which aliens do not exist. — Srap Tasmaner

Isaac

10.3kthere is a possible world in which aliens do not exist. — Srap Tasmaner

What would render a world impossible? Are possible worlds all those which are allowed logically? If so, how does one express the possibility of one having made an error in logic? -

Michael

16.9kBut no one ever says "I know for a fact there are three left, but I could be wrong."

Michael

16.9kBut no one ever says "I know for a fact there are three left, but I could be wrong."

Why not? — Srap Tasmaner

Also on this, the entire point of Moore's paradox is that there is something that we would never say as prima facie it would be absurd even though it isn't a logical contradiction and is sometimes even true. Perhaps the same sort of thing is going on here. -

Relativist

3.6k1. I believe with justification that John is a bachelor

Relativist

3.6k1. I believe with justification that John is a bachelor

2. My belief might be wrong

3. John is a bachelor

4. Therefore, my true (from 3) justified belief (from 1) might be wrong (from 2) — Michael

Premises 1 and 2 reflect your beliefs

Premise 3 is a statement of fact that is independent of your beliefs

This makes your conclusion (as written) a bit misleading, because it's written as if you know* #3. If you know #3, then it is not possible for you to be wrong.

*("to know x" = to justifiably believe x & x is true & not a Gettier case) -

Michael

16.9k

Michael

16.9k

I'm not presenting any of those premises as something like personal belief-assertions. They are intended as statements of fact, as is usually the case when we make arguments like these. Would it be clearer in the third-person, and perhaps with a material implication?

One of these is valid:

Argument 1

a. Jane believes with justification that John is a bachelor

b. Jane's belief might be wrong

c. Therefore, John is not a bachelor

Argument 2

a. Jane believes with justification that John is a bachelor

b. Jane's belief might be wrong

c. Therefore, if John is a bachelor then Jane's justified true belief might be wrong -

Relativist

3.6kBoth are invalid.

Relativist

3.6kBoth are invalid.

The language is misleading because there are two different modalities within the argument: epistemic and metaphysical. I think this is the source of your confusion.

The statement (a), "Jane believes with justification John is a bachelor" needs unpacking. I infer that this means: "Jane believes John is a bachelor" and that this is a categorical belief. A categorical belief doesn't express any degree of doubt at all.The fact that this belief is justified, implies that - based on her background beliefs, that she believes it is necessarily the case that John is a bachelor. This reflects epistemic necessity (a weaker modality than metaphysical).

The statement (b), "Jane's belief might be wrong" sounds equivalent to: "it is metaphysically possible that Jane's belief is false". How could she be so certain, and yet still be wrong? Because there could be additional facts she's unaware of, or because one or more of her background beliefs is false.

So....

Argument 1 is invalid. The conclusion does not follow from the premises.

Argument 2 is invalid. If John is a bachelor, then her justified belief is true - it is not metaphysically possible for it to be false.

If you disagree, I suggest rewording your arguments with clarification of the modality for each modal statement. -

Michael

16.9kArgument 2 is invalid. If John is a bachelor, then her justified belief is true - it is not metaphysically possible for it to be false. — Relativist

Michael

16.9kArgument 2 is invalid. If John is a bachelor, then her justified belief is true - it is not metaphysically possible for it to be false. — Relativist

Argument 2

a. Jane believes with justification that John is a bachelor

b. Jane's belief might be wrong

c. Therefore, if John is a bachelor then Jane's justified true belief might be wrong

I'll rephrase it:

a. Jane believes with justification that John is a bachelor

b. Jane's belief might be wrong

c. Therefore, if John is a bachelor then a) is true and b) is true and John is a bachelor

Does the conclusion follow?

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum