-

Direct realism about perceptionNo. Humans do not experience neural representations; experience is having neural representations.

You are not separate from your neural processes. — Banno

We experience (are aware of) something when we dream, when we hallucinate, (when we have synaesthesia?), etc., and these things are not distal objects in the world. The indirect realist claims that these things we experience when we dream etc. are mental/neurological phenomena, that we also experience these things when we have ordinary waking experiences, and that these things satisfy the philosophical notion of directness.

So which of these is your counterclaim?

1. We don't experience (are not aware of) anything when dream, when we hallucinate, (when we have synaesthesia?), etc.

2. Those things we experience when we dream etc. are not mental/neurological phenomena

3. We do not experience these things when we have ordinary waking experiences

4. These things do not satisfy the philosophical notion of directness

Note specifically that I haven't yet said that we don't directly perceive distal objects in the world when we have ordinary waking experiences. The above is just to see if we can agree that we do (also?) directly perceive mental/neurological phenomena (even during ordinary waking experiences) -

Direct realism about perceptionOrdinary causal media do not introduce a layer whose outputs can succeed or fail as presentations of the environment. — Esse Quam Videri

This is the thing I'm trying to make sense of. What does it mean, for example, for 700nm light to "succeed" as a presentation of a strawberry and 450nm light to "fail" as a presentation of a strawberry?

You appeared to accept before the plausibility of the inverted spectrum, so let's assume that the phenomenal character I experience when my eyes detect 700nm light is the same as the phenomenal character you experience when your eyes detect 450nm light and vice versa. You are wearing a visor that transforms 700nm light into 450nm light and I'm not wearing a visor. When you and I look at a strawberry we now experience the same phenomenal character.

In what sense has your visor "failed" to present the strawberry to you? And why do we not ask if my eyes have "failed" to present the strawberry to me? -

Direct realism about perceptionit does not follow that perceptual content is therefore about neural states rather than mind-external objects — Esse Quam Videri

I didn't say that it's about neural states. I'm saying that phenomenal experience is neural states (or emerges from them). My concern is the relationship between these neural states and distal objects. There is certainly a causally covariant relationship, but nothing more substantial than that. The distal object and its properties are not "present" in the neural states, and nor does the distal object have a "real appearance" that is "transmitted" via light or vibrations and "into" these neural states.

I reject that bridge principle. On my view, appearances are not intrinsic properties transmitted from object to perceiver, nor are they mental projections; they are relational ways objects are perceptually available to situated perceivers under specific conditions. This does not require that anything like an appearance be “carried” through space as a non-physical property. It requires only that perceptual states be individuated in part by their relations to mind-external objects—by the causal and counterfactual dependencies that link those states to the objects they are experiences of. In that sense, perceptual content is world-involving rather than internally bounded: what the state is about is constitutively tied to the object, not merely causally downstream of it. Science tells us how perceptual states are realized and transmitted; it does not by itself determine whether their content is world-involving or confined to the head. That question is exactly what separates internalism from externalism, and it cannot be settled by physics alone. — Esse Quam Videri

All of which is consistent with the presence of a visor. If the phenomenal character of experience is not a "representation" of some supposed "real appearance" then a) what does it mean for the image on the screen to be an "inaccurate" representation of the distal object and b) why does it matter if it is? Either way, the phenomenal character of experience is its own thing. It just seems like special pleading when you previously said that light "transmits an object’s own appearance" but then argue that the the visor doesn't. What does light "succeed" in doing that the visor "fails" in doing? -

Direct realism about perceptionDirectness is not defeated by more mediation, but by a change in kind—from causal conduits that transmit an object’s own appearance to representational systems whose accuracy must be relied upon. — Esse Quam Videri

So this is the exact naive realism that we discussed before. A thing's appearance, e.g. it's shape, orientation, colour, smell, taste, etc. is not something that is inherent in the object and then "transmitted" via some medium like light or vibrations or microscopic molecules in the air and into the phenomenal character of experience. To risk being overly reductive, there is just a collection of particles situated in space that interact with other particles in their immediate vicinity according to deterministic (or stochastic at the quantum scale) laws, which in turn interact with other particles in their immediate vicinity, etc., eventually interacting with the particles that make up someone's sense receptors and then the particles that make up someone's brain. The phenomenal character of experience (the appearance) is then either reducible to the behaviour of these brain-particles (if eliminative materialism is correct) or emerges from them. The suggestion that this phenomenal character — i.e. the "movements" of these particles — counts as the "direct presentation" of the “real” appearance of some distant collection of particles (but not any of the physically intermediate particles for some reason) makes no sense. That's just us naively projecting appearances out into the world, like a phantom itch. -

Direct realism about perception

It's not metaphor or analogy, just as "I feel pain" is not metaphor or analogy (which also doesn't require anything like a Cartesian theatre or a homunculus). -

Direct realism about perceptionThe suggestion that you're watching your own mental activity is the Cartesian theater in a nutshell, my friend. — NOS4A2

I'm not saying that I'm watching my own mental activity. I'm saying that the schizophrenic hears voices when his auditory cortex is active and even if he doesn't have ears, and that these voices he hears are mental phenomena. I'm saying that the synesthete can see colours in a dark room. I'm saying that those with cortical deafness don't hear anything even if their eardrums function normally. I'm saying that the flower might react to and move towards the light but it doesn't see or feel or hear the Sun. I'm saying that experience and its qualities are either reducible to or caused by complex neurological behaviour. -

Direct realism about perceptionSo when you see something without eyes, where in time and space is this something you see — NOS4A2

Where in time and space is this something you dream about? Where in time and space is this something you hallucinate? Where in time and space are the colours the synesthete sees when listening to music?

In the head.

how are you seeing it? — NOS4A2

How are you dreaming about something? How are you hallucinating something? How are you thinking about something?

Because the appropriate areas of the brain, e.g the visual cortex, are active. -

Direct realism about perceptionIt means that perception does not proceed by inference from an inner surrogate. — Esse Quam Videri

The error, if there is one, lies in the judgment “the apple exists now”, not in the perceptual relation itself. — Esse Quam Videri

It's not clear to me what you mean by perception, which is probably why I don't understand what you mean by direct perception. The first quote seems to suggest it has something to do with inference but then the second quote seems to suggest that it's distinct from judgement. Could you clarify?

If it helps, consider the visor example before but assume that the person wearing the visor doesn't know that he's wearing a visor and that he believes that he has direct perception of distant objects. You've accepted before that this is indirect perception, but also said that this is because we must also judge the "accuracy" of the visor. In this case the wearer doesn't judge the "accuracy" of the visor because he doesn't even know about it. So given this, what is the difference between the visor being an intermediary and the visor being "the means by which the apple is perceptually available across space and time"? As I said once before to Banno, as he made a similar claim, the latter phrase seems like it can act as a truism that includes even a Cartesian theatre.

The proximal stimulation is not something we perceive instead of the object; it is how the object makes itself perceptually available within the physical world’s causal structure. That distinction allows us to acknowledge causal mediation without collapsing perception into awareness of inner or outer surrogates. — Esse Quam Videri

What if the light first passes through a window? What if the light has been reflected off a mirror? Like above, assume in both cases that we don't know about the window or the mirror. When, exactly, does causal mediation stop "maintaining" direct perception? -

Direct realism about perceptionNow that we know seeing doesn’t involve eyes — NOS4A2

It doesn't necessarily involve eyes, but most of the time it does.

how are you looking at them? — NOS4A2

Seeing something doesn't require looking at something, just as hearing something doesn't require pointing one's ears at something. We see something if the visual cortex is active in the right kind of way, and we hear something if the auditory cortex is active in the right kind of way, and we think about something if the relevant areas of the brain are active in the right kind of way.

where do the objects of perceptions appear — NOS4A2

This is like asking where the objects I dream about or hallucinate appear. It's a nonsensical question. There is just the occurrence of mental phenomena, with qualities described by such words as "pain", "pleasure", "red", "round", "sweet", "sour", etc. -

Direct realism about perceptionThen how do those cortexes see? — NOS4A2

The activation of these cortices is seeing, just as the activation of other areas of the brain is thinking and is feeling pain. -

Direct realism about perceptionIs it your position, then, that sensing doesn’t involve sense receptors? — NOS4A2

No, my position is that to see something is for the visual cortex to be active and that to hear something is for the auditory cortex to be active. Most of the time this involves sense receptors being the "source" of the signal that triggers the activation of these cortices, but this isn't necessary. This explains how schizophrenics hear voices, why those with cortical deafness don't hear anything, and the existence of synesthesia. -

Direct realism about perceptionThat’s just the figurative language — NOS4A2

There's nothing figurative about the phrase "the schizophrenic hears voices". The problem here is that you seem to think that the verb "to hear" refers only to the ears reacting to vibrations in the air, but it doesn't. This is most evident in those with cortical deafness who don't hear anything despite having perfectly functional ears. To hear something is for the auditory cortex to behave in a certain way, regardless of what, if anything, is happening in the ears. In ordinary situations the auditory cortex is only sufficiently active in response to signals from the ears, but it's a mistake to conflate the two. -

Direct realism about perceptionI also reject the claim that temporal mediation entails that the object of perception must be a present mental item. — Esse Quam Videri

I suppose there are two related claims:

1. The direct object of perception is a distal object

2. The direct object of perception is a mental phenomenon

It's possible that both (1) and (2) are false.

Carrying on from the argument here, let's assume a world in which light travels at 1m/s. An apple is placed in front of me at a distance of 10m. After 5 seconds it is disintegrated. After a further 5 seconds I see an intact apple.

Is the apple the direct object of my perception?

If it is then the direct object of my perception is something that doesn't exist, which is somewhat peculiar.

If it's not then what is the direct object of my perception, and at what (non-arbitrary) speed does light have to travel and at what (non-arbitrary) distance does the apple have to be for it to be the direct object of my perception? -

Direct realism about perceptionLight takes 8 min 20 sec to travel from the Sun to the Earth. The Sun we look at now in the present is not the same Sun as it was in the past 8 min 20 sec ago. The Sun is continually changing. — RussellA

I recall an argument from somewhere that argued something to the effect of:

P1. We directly perceive a distal object only if that object exists

P2. Many of the stars we see in the night sky no longer exist

C1. Therefore, many of the stars we see in the night sky are not directly seen

P3. The manner in which we see a star that still exists is the same as the manner in which we see a star that no longer exists

C2. Therefore, none of the stars we see in the night sky are directly seen

P4. The manner in which we see a star is the same as the manner in which we see any distal object that emits or reflects light, regardless of distance

C3. Therefore, no distal object is directly seen

So at best we only directly see light (leaving mental phenomena aside for the moment). -

Direct realism about perception

Then let's make it even simpler.

There are two wavelengths of light: 1nm and 2nm. There are two neurons in the brain responsible for colour experience: A and B.

When John's eyes detect 1nm light his A neuron is active and he describes the colour he sees as red and when his eyes detect 2nm light his B neuron is active and he describes the colour he sees as blue.

When Jim's eyes detect 1nm light his B neuron is active and he describes the colour he sees as red and when his eyes detect 2nm light his A neuron is active and he describes the colour he sees as blue.

We then directly stimulate these neurons when their eyes are closed, asking them to describe the colour they see, and their answers will be consistent with the above.

Assuming eliminative materialism (to avoid positing non-physical phenomena), experiencing a particular colour just is a particular neuron being active. Given that when John's eyes detect 1nm light his A neuron is active and when Jim's eyes detect 1nm light his B neuron is active it must be that John and Jim are having different experiences when their eyes detect 1nm light even though they both refer to their experience as "seeing red".

We then rewire Jim's brain so that, like John, his A neuron is active when his eyes detect 1nm light and his B neuron is active when his eyes detect 2nm light, shine a 1nm light into his eyes, and ask him what colour he now sees. He'll say "blue". -

Direct realism about perception

Dreams and hallucinations can be coloured (or "have colour" if you prefer), and people with synaesthesia can see colours when listening to music. This is because seeing colours (or even coloured things) is what happens when the visual cortex is active in the right kind of way, regardless of what the eyes are doing or what objects exist at a distance. This is also why cortical blindness is a thing, where the eyes react to stimuli as normal but the person doesn't see anything.

None of this entails a homunculus. That's a tired and lazy strawman. -

Direct realism about perception

I think you're confusing two different arguments.

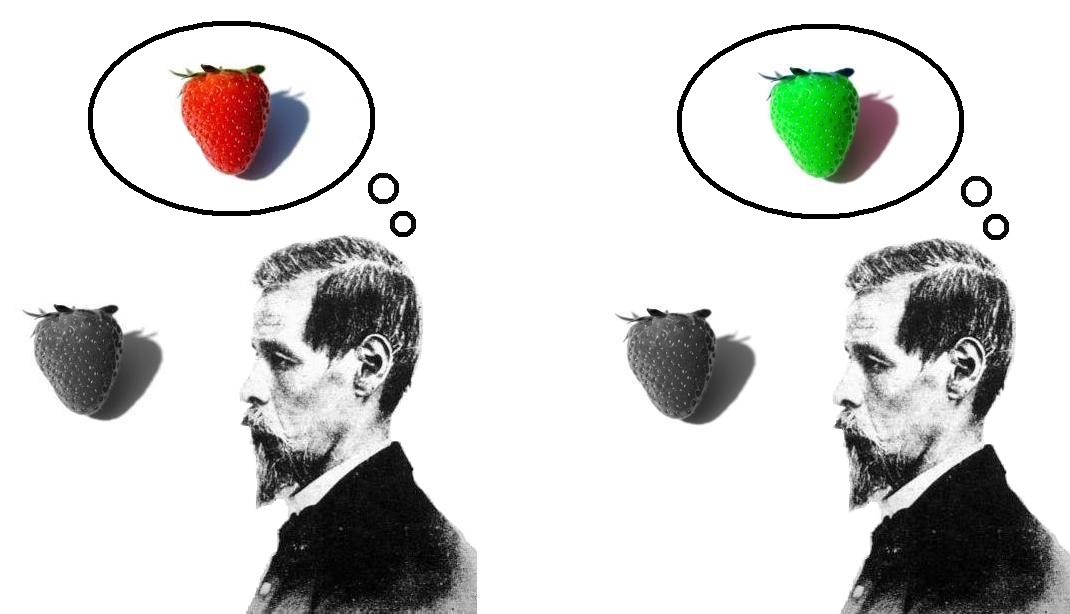

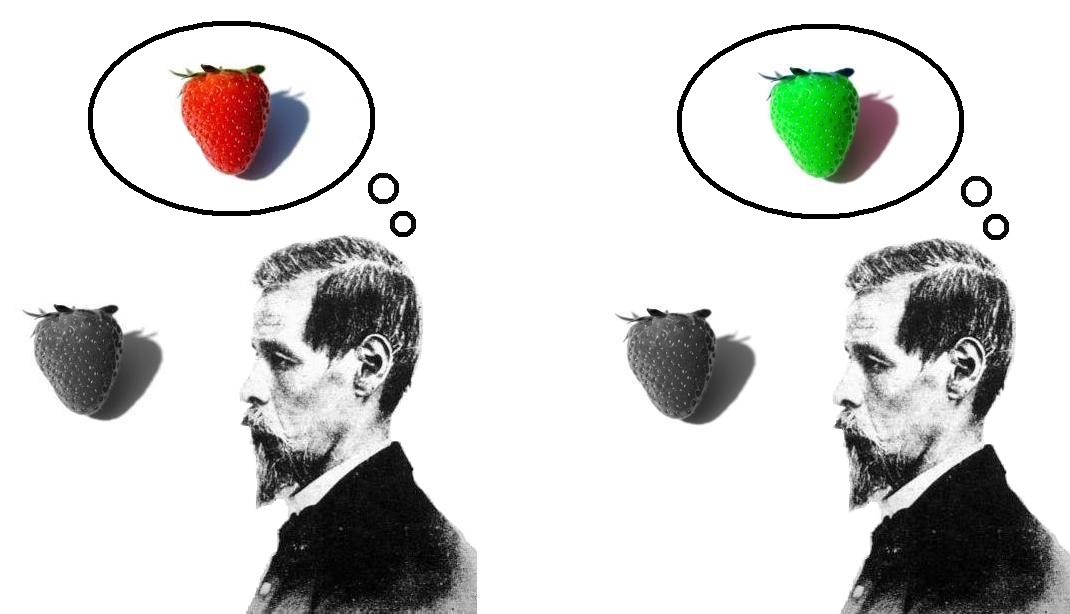

The first argument is that a scenario like the below is intelligible, and even plausible. Different people can have difference experiences (i.e. because their visual cortices are behaving differently) even if they use the same words. John and Jim each see different colours but when asked to describe the strawberry say "the flugleberry is foo-coloured" in their language. I then extended this to cover not just colour but also orientation. What John sees when standing upright is what Jim sees when hanging upside down even though they both use the word "up" to describe the direction of the sky and "down" to describe the direction of the ground.

My criticism with your response is that we don't need to be able to determine that John and Jim are having different experiences for them to be having different experiences. They just either are or they aren't as determined by what their brains are doing, regardless of whether or not we have the practical means to compare the two.

The second argument is that the words do, in fact, (also) refer to our private experiences. As an example of this, consider the people with the visors. The visors have been constructed in such a way that when the sensors on the outside detect 700nm light they output on the screen 500nm light and vice-versa. These people use the word "red" to describe the colour of strawberries and associate the colour red with 700nm light and use the word "green" to describe the colour of grass and associate the colour green with 500nm light.

Then when they're asleep we fix their visors so that the light emitted by the screen matches the light detected by the sensors. When they wake up do they go about their day as if nothing has changed, continuing to use the word "red" to describe the colour of strawberries and associate the colour red with 700nm light and to use the word "green" to describe the colour of grass and associate the colour green with 500nm light? Or do they immediately ask "why are strawberries now green?" and "why is grass now red?" and then be very confused when nothing about strawberries, grass, or the light they each reflect has changed?

I think the latter is obviously what will happen, showing that even though the use of the words "red" and "green" was public the words primarily referred to the colours on their private screen (assuming direct realism for the sake of argument) and not whatever was happening in their shared environment. -

Direct realism about perceptionHow could you ever determine that what the chap on the left sees is different to what the chap on the right sees? — Banno

We probably can’t, save for perhaps opening their heads and checking to see which neural correlates are active. It stands to reason that if their visual cortices are behaving differently then they are having different experiences, even if they utter the same words when asked to describe the strawberry. But that's not something we can practically do, especially not in everyday life and especially not if we're not a technologically advanced society.

As a less theoretical example, a language doesn't need to exist for it to be possible that some see the dress to be white and gold and others black and blue. They just either see it to be one set of colours or they don't, regardless of whether or not they can ask each other about it.

It's honestly quite surprising that you of all people are suggesting that something is true only if we can determine that it's true. That's very antirealist of you. -

Direct realism about perception

You don't need to believe in non-physical mental phenomena to accept that experience is something the brain does. We see and hear things when the visual and auditory cortices are active, regardless of what things caused this to happen (whether internal to the body or external). If the visual cortex is active in the right kind of way we see colours, even if our eyes are closed and we're in a dark room, e.g. if we have chromesthesia and are listening to music. However you choose to "cash out" these colours they are evidently not the "direct presentation" — in the philosophically relevant sense of the phrase — of something like an apple's surface, and are the medium through which we are made aware that something (probably) exists at a distance (either reflecting light or, for those with chromesthesia, vibrating the air). -

Direct realism about perceptionSo then no medium — NOS4A2

The phenomenal character of experience is the medium, e.g. colours, which can differ between individuals despite looking at the same object and interacting with the same wavelengths of light. -

Direct realism about perceptionIf there is no visor or screen, through which medium are you viewing an apple indirectly? — NOS4A2

The phenomenal character of experience; the thing that occurs when we dream, when we hallucinate, and also when we're awake and looking at real objects in the world. -

Direct realism about perceptionIt was part of a larger argument. Their direction and the fact that they interact with the environment allow anyone to explain how we can see an apple, for example, while it precludes you from doing the same. You have no way to explain how you can see a perception, or some other mind-stuff, and are resigned to illustrating diagrams of apples in thought-bubbles floating around a head. — NOS4A2

On indirect perception of apples:

A society of people who wear visors with sensors on the outside and a screen on the inside that displays a computer-generated image of the outside can see apples, albeit indirectly. There's nothing problematic about this. The indirect realist simply argues that this sort of indirect perception of apples happens even without the visor and its screen.

On direct perception of mental phenomena:

Despite your previous objections to the language, it is perfectly ordinary and correct to say that schizophrenics see and hear things when they hallucinate. The things they see and hear are mental phenomena, not nothing — else there would be no distinction between hallucinating something and not hallucinating anything, or between a visual hallucination and an auditory hallucination, or between a visual hallucination of one thing and a visual hallucination of another thing. This sense of seeing and hearing things also occurs during "veridical" perception, and it is only in virtue of this that we see and hear objects in the world — e.g. if there's damage in the visual and auditory cortexes but otherwise functional eyes and ears then we don't see or hear anything. -

Direct realism about perceptionYour response attempts to push the discussion back into the traditional framing, whereas my view rejects that framing. — Esse Quam Videri

I think the issue I have is that you're arguing that the traditional dispute is framed wrong whereas I think that the traditional dispute just means something else by "direct perception". So perception might not be direct in the way that they mean even if it's direct in the way that you mean. Once again, I'll refer to semantic direct realism.

Regardless, thanks for the discussion. -

Direct realism about perception

There isn't a shared assumption of "phenomenal mirroring". There is the direct realist's claim that there is "phenomenal mirroring", because that is what it would mean for ordinary objects to be "directly present" in experience, and the indirect realist's claim that there might not be "phenomenal mirroring", because ordinary objects are not "directly present" in experience.

As for the "epistemic intermediary" I still fail to understand what you mean by the term. All indirect realists would mean by it is that we believe that the ball is blue and round because the ball appears blue and round, and that this appearance is a mental phenomenon, not the "direct presentation" of the ball's colour and shape. -

Direct realism about perception

I disagree with your assertion that we must be able to determine which group someone belongs to for there to be two different groups.

A scenario like the below, where two humanoid aliens agree that the strawberry reflects 400nm light and that the proposition "the blugleberry is foo-coloured" in their language is true, is intelligible:

-

Direct realism about perceptionSenses have a direction that tends toward the outside of the body. — NOS4A2

What does it mean to say that senses have a "direction"?

It’s why we have those holes in our skull where our eyes, nose and mouth are, so they can better interact with the environment. It’s why you turn your head towards something or open your eyes in order to see it better. — NOS4A2

If you just mean to say that (most of) our sense receptors are situated on the outside of our body and react to things that exist outside the body then, to be blunt, no shit.

If you think that this is all it means for perception to be direct then you're very mistaken. Indirect realists don't disagree with any of the above.

Like your prior suggestion that we directly perceive an object if (and only if?) our sense organs are in direct physical contact with the object perceived, you're presenting a very impoverished interpretation of the issue. -

Direct realism about perceptionThe visor-and-screen case counts as indirect precisely because it introduces such a surrogate: the subject’s epistemic access runs through an internally generated stand-in whose adequacy must be assessed. That is not true in ordinary perception, even though both cases involve world-directed judgments. — Esse Quam Videri

Then we're back to what I asked in this post (which I'll repeat below), which I don't think was addressed:

What's the difference between a bionic eye that is "integrated into perception such that judgments are still answerable to objects through ongoing interaction and correction" and a bionic eye that is "a surrogate whose adequacy depends on a generating process that stands in for the world"?

It just seems like there's a lot of special pleading here.

Whether an organic eye or a bionic eye, there is something that takes electromagnetic radiation as input, carries out transduction according to some deterministic process, and then stimulates the optic nerve.

Without begging the question or engaging in circularity, what determines whether or not the physical intermediary between the electromagnetic radiation and the optic nerve is an epistemic intermediary?

I don’t think there’s a non sequitur here once my notion of “directness” is kept in view. — Esse Quam Videri

As I said before, you can mean anything you like by "directness". I'm concerned with what it means in the context of the traditional dispute between direct and indirect realism, which I summarised here (which I'll repeat below), and which I also don't think was addressed:

The direct realist argues that the sky appears blue because a) the sky is blue and b) the sky is directly present in experience. The indirect realist argues that this argument fails because (b) is false.

Even if there's an interpretation of (a) such that (a) is true, indirect realists aren't arguing that (a) is false; they are arguing that (b) is false. And they aren't arguing that any and all interpretations of (b) are false but that a particular interpretation of (b) is false; specifically, the interpretation of (b) such that if it were true, and if the sky appears blue, then (a) is true according to a naive interpretation of (a). -

Direct realism about perceptionI would say that orientation is frame-relative in a way that shape is not. — Esse Quam Videri

Shape as seen or shape as felt? Because these are very different things. Studies on Molyneux's problem show that those born blind who have their sight restored "had no innate ability to transfer their tactile shape knowledge to the visual domain".

So is the mind-independent "shape" of an object similar to the look of a shape or the feel of a shape? Or is it similar to neither, and like colour we using a word like "circle" to refer to distinct things that are causally related but fundamentally different?

Or for something that might be less tricky to understand; what looks to be a smooth circle with the naked eye may look very different through a pair of binoculars or a microscope. Which "zoom" or "scale" counts as the "real" shape of an object? Same question when discussing something as simple as the distance between two points (2cm looks very different through a magnifying glass). -

Direct realism about perceptionColour is plausibly response-dependent in a way that shape and orientation are not. Ordinary claims about shape and orientation track relatively stable, mind-independent structural features of objects — and that’s why geometrical error correction, measurement, and intersubjective agreement work the way they do. — Esse Quam Videri

Then to incite a more controversial topic:

Consider that there are two subspecies of humanity such that what one sees when standing upright is what the other sees when standing upside down. Both groups use the word "up" to describe the direction of the sky and "down" to describe the direction of the floor. Firstly, is this logically plausible? Secondly, is this physically plausible? Thirdly, does it make sense to argue that one subspecies is seeing the "correct" orientation and the other the "incorrect" orientation? Fourthly, if there is a "correct" orientation then how would we determine this without begging the question?

If it's difficult to imagine, consider two astronauts top and tail in space or standing on opposite sides of a ringworld looking at the Earth. From the perspective of one the North Pole is as the top and from the perspective of the other the South Pole is at the top. Neither is the "correct" perspective as there are no privileged viewpoints. Now retain their orientation relative to one another but bring them to Earth. Is there some distance from the ground such that one of their perspectives becomes the "correct" orientation?

Calling my view “Cartesian” doesn’t address the issue I’ve been pressing. The Cartesian Theatre is defined by the presence of an epistemic surrogate whose adequacy must be evaluated. My whole point has been that once phenomenal experience is not truth-apt, treating it as the “immediate object of perception” does no epistemic work. If that move reclassifies the traditional taxonomy, so be it—but that’s a consequence of rejecting phenomenal-first assumptions, not a reductio. — Esse Quam Videri

I'm not calling your view Cartesian. I'm saying that the scenario with the visor and the screen functions like a Cartesian Theatre. This would clearly be indirect perception even though their perceptual judgement "there is a ship" is about an object in the world.

So your claim that "perception is cashed out entirely in terms of perceptual judgment, and perceptual judgments are about objects in the world ... [therefore perception is direct]" is a non sequitur. -

Direct realism about perceptionI've granted that "blueness" is not a property of the sky, yet I maintain that "the sky is blue" is true. This sounds like a contradiction, but I don't think it is.

I would say that ordinary perceptual judgments like "the sky is blue" do not have to be interpreted in a naive way, but can be interpreted as something like "under normal viewing conditions, the sky systematically elicits blue-type visual responses in normal perceivers". This makes the claim objective, fallible, publicly assessable and non-projective. Nor does it require that the sky instantiate a phenomenal property as experienced. Many of the claims that people make ("the sun is rising", "that table is solid") can be cashed out in similar terms without resorting to naive realism. — Esse Quam Videri

So there's an interpretation of (a) such that (a) is true. However, notice that indirect realists aren't arguing that (a) is false; they are arguing that (b) is false. And they aren't arguing that any and all interpretations of (b) are false but that a particular interpretation of (b) is false; specifically, the interpretation of (b) such that if it were true, and if the sky appears blue, then (a) is true according to a naive interpretation of (a).

But out of curiosity, would you make the same claims about shape and orientation (and other features of geometry) that you make above about colour?

It's not conflation, it's deflation. In the view I am defending, perception is cashed out entirely in terms of perceptual judgment, and perceptual judgments are about objects in the world. That’s not to deny that sensation causally mediates perception, only that it epistemically mediates it. — Esse Quam Videri

Then I'll repeat what I said to Banno in my last comment to him: I think the visor and its screen functions exactly like a Cartesian theatre (which is a strawman misrepresentation of indirect realism), and a Cartesian theatre is exactly the sort of thing that would qualify as indirect perception. So you've defined "direct realism" in such a way that even the strawman misrepresentation of indirect realism would count as direct realism.

It's so divorced from the actual (traditional) dispute between direct and indirect realism that it's not deflation but ... avoidance? -

Direct realism about perceptionIf you agree that phenomenal experience cannot be correct or incorrect, then the hypothesis that phenomenal experience is "what is directly seen" no longer explains error or motivates the skeptical worries you have presented. — Esse Quam Videri

The skeptical worry is that the sky appears blue but might be green (or not coloured at all, because colour is a "secondary quality") and that the ball appears round but might be cubed (or not shaped at all, because shape is a "secondary quality"). The direct realist tries to avoid this by arguing that the sky appears blue because a) the sky is blue and b) the sky is directly present in experience. The indirect realist argues that this argument fails because (b) is false.

You appear to be arguing that (a) is a category error (i.e. colour is not even the sort of property the sky can have). That neither proves direct realism nor disproves indirect realism. If anything, it proves indirect realism because if (a) is a category error then (b) is false.

My point has been that the direct object of perceptual judgments ("That's a ship") are objects in the world. Another way to say this is that perceptual judgments about objects in the world (ships), not phenomenal contents (redness as-seen, sourness as-tasted, etc). And this pretty much brings us full circle to where we landed a few posts back. — Esse Quam Videri

And so we circle back to the example with the visors. The judgement "there is a ship" is a judgement about an object in the world, but it still involves indirect perception of the ship given the visor and the screen. You seem to be conflating the immediate objects of perception and the things our judgements are about. These are not the same thing. -

Direct realism about perception

What do you mean by senses "pointing" outward? The physics and physiology is just nerve endings reacting to some proximal stimulus (e.g. electromagnetic radiation, vibrations in the air, molecules entering the nose, etc.) and then sending signals to the brain. If there's any kind of "motion" involved, it certainly does appear to be towards the head. -

Direct realism about perception

We start with the naive view that there is (usually) a match between the phenomenal character of experience and the world. The sky is blue in the exact same way as blueness is present in visual experience and the ball is round in the exact same way as roundness is present in visual experience. We can trust that this is so because the sky and the ball are "directly present" in experience; experience isn't just some distinct neurological or mental phenomenon but an "openness to the world". And this is understandable, particularly with distance being a feature of visual experience. It really seems as if experience extends beyond the body to encapsulate the environment.

The indirect realist then argues that experience is just a neurological or mental phenomenon and so the sky and the ball are not "directly present" in experience in this way. Because of this, it is possible that the sky appears blue to us but is in fact green (or not coloured at all, because colours are "secondary qualities") and that the ball appears round to us but is in fact a cube (or not shaped at all, because shapes are "secondary qualities"). When I see the sky the "immediate object of assessment" is the colour blue, which is a mental phenomenon, and when I see the ball the "immediate object of assessment" is the round shape, which is a mental phenomenon.

I think that the distinction you're making here is more terminological than substantive — Esse Quam Videri

I would say the same about your claim that experience isn't the sort of thing that can "succeed" or "fail" at "lin[ing] up with how things are".

Just because an apple isn't a "representation" it doesn't follow that we can't say that its features/properties do or don't match the features/properties of some other apple (or some other fruit).

In the case of naive realism, the claim is that the features/properties of experience do match the features/properties of the apple (in the veridical case), in the sense of both type identity and token identity. The indirect realist argues that this token identity fails and so this type identity possibly fails.

And if we find that colours and shapes aren't even the sort of properties that the sky and the ball can have (which I think we have, at least with respect to colour) then that's just proof of indirect realism as I see it. -

Direct realism about perceptionYou’re treating phenomenal character as that which is assessed for correctness in the act of perception — Esse Quam Videri

No, I'm saying that it's the thing directly seen. From this we then make judgements about the world that can be correct or not (if indeed we do; much of the time I experience things without making any kind of judgement). -

Direct realism about perceptionIn veridical perception, that judgment is answerable to objects in the environment and can be corrected by further interaction with them. In hallucination, the same kind of judgment is made, but it fails—there is no object that satisfies it. No inner surrogate is thereby promoted to the status of what is assessed; rather, the judgment is simply false. — Esse Quam Videri

As I said a few days ago, these judgements do not occur apropos of nothing. Excluding the obvious cases of mathematics and logic, it is the phenomenal character of experience that prompts and directs our judgements. I say "there is a white and gold dress" when the appropriate visual phenomena occurs. If the experience is veridical (to the extent that colour experiences can be veridical), the judgement is true. If the experience is an hallucination, the judgement is false. In either case it is the visual phenomena (including its character) that acts as "immediate object of assessment". -

Direct realism about perceptionIf the bionic eye is integrated into perception such that judgments are still answerable to objects through ongoing interaction and correction — as with natural, transplanted, or lab-grown eyes — then there is no epistemic intermediary, and perception is direct in the sense I’m using.

The visor and nerve-stimulation cases differ because they interpose a surrogate whose adequacy depends on a generating process that stands in for the world, rather than being part of the perceptual relation itself. — Esse Quam Videri

What's the difference between a bionic eye that is "integrated into perception such that judgments are still answerable to objects through ongoing interaction and correction" and a bionic eye that is a "surrogate whose adequacy depends on a generating process that stands in for the world"?

It just seems like there's a lot of special pleading here.

Whether an organic eye or a bionic eye, there is something that takes electromagnetic radiation as input, carries out transduction according to some deterministic process, and then stimulates the optic nerve.

Without begging the question, what determines whether or not the physical intermediary between the electromagnetic radiation and the optic nerve is an epistemic intermediary? I don't think there is such a thing, e.g. proteins are not privileged over silicon.

So either perception is direct both with the bionic eye and the organic eye or perception is indirect both with the bionic eye and the organic eye.

If you say that perception is direct both with the bionic eye and the organic eye then we return to the Common Kind Claim: whatever is the "immediate object of assessment" when the eye (whether bionic or organic) is "malfunctioning" must also be the "immediate object of assessment" when the eye isn't "malfunctioning" — and in the former case that thing cannot be an object in the external world because the thing we're seeing doesn't exist in the external world; therefore in the latter case that thing cannot be an object in the external world either. -

Direct realism about perceptionI would say that there is no relevant difference of the kind you are asking for — because the distinction I’m drawing is not about the material or biological status of the causal chain at all — but about the epistemic role it plays.

In ordinary perception — regardless of whether the eye is natural, transplanted, or artificially grown — one’s judgments are answerable to objects in a shared environment through ongoing interaction and correction... — Esse Quam Videri

So why is this not also the case for the bionic eye? It simply replaces rod and cone cells with silicon chips. -

Direct realism about perceptionIn both cases, what the subject’s judgments are immediately answerable to is a generated input whose correctness depends on how it was produced, rather than to the objects themselves. That is the sense in which the perception is indirect. — Esse Quam Videri

Then what is the relevant difference between these:

1. An artificial bionic eye

2. An artificial organic eye (identical to a natural eye, but grown in a lab)

3. A transplanted natural eye

4. The natural eye one was born with

All work by taking electromagnetic radiation as input and then stimulating the optical nerve according to some deterministic process. -

Direct realism about perceptionThe visor case is instructive precisely because it introduces an epistemic intermediary whose outputs are the immediate objects of assessment. — Esse Quam Videri

So let's amend the scenario slightly. Instead of there being a screen on the inside that outputs light towards the eyes it has wires connected directly to the optical nerves and stimulates them in the "appropriate" way, i.e. the visor is a "bionic eye".

Would you still accept that these people only have indirect perception of the world beyond the visor, or does it now qualify as direct perception? What are the immediate objects of assessment? If the Common Kind Claim is to be believed then whatever are the immediate objects of assessment when the bionic eye is malfunctioning (e.g. causing their wearers to see things that aren't there) are also the immediate objects of assessment when it's working as intended. -

Direct realism about perceptionFor the direct realist, the chain is the mechanism by which the world shows itself... — Banno

The problem with this is that it makes the word "direct" in the phrase "direct perception" meaningless. This is highlighted by your assertion that these people with their visors still directly perceive their shared environment. You appear to be arguing that the visor and its screen is "the mechanism by which the world shows itself".

Whereas I think this visor and its screen functions exactly like a Cartesian theatre, and a Cartesian theatre is exactly the sort of thing that would qualify as indirect perception (but isn't required for indirect perception, as I've argued before). So you've defined "direct realism" in such a way that even the strawman misrepresentation of indirect realism would count as direct realism.

And while they are seeing the image on the screen and they are seeing the ship and they are talking about the ship, each of these has a slightly differing sense, each is involved in a different activity. — Banno

According to the indirect realist, the same is true ("each of these has a slightly differing sense") even without the visor.

1. There is perceiving mental phenomena (e.g. colours in the sui generis qualitative sense of the term) — which is not to be understood in the sense of a Cartesian theatre but in the sense of the seeing and hearing that (also) happens when we dream and hallucinate.

2. There is perceiving distal objects (e.g. a dress).

3. There is talking about the mental phenomena (e.g. "I see white and gold").

4. There is talking about the distal object (e.g. "there is a dress").

The substantive philosophical claims are that a) (2) only happens in virtue of (1) and that b) (2) does not satisfy the philosophical notion of directness, e.g. as explained here — with the example of the visor showing that (2) doesn't need to be direct for (4) to happen.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum