Comments

-

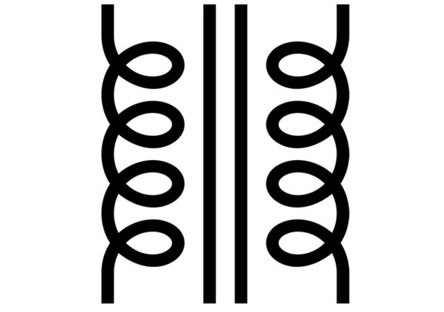

Continua are Impossible To Define Mathematically?Nevertheless, the point I am making is that I can find no workable mathematical description of continua. This might lend credence to the idea that, like matter, time and space are discrete? — Devans99

If by workable you mean conformity to your private intuition of the continuum, then actual mathematicians have famously wrestled with this. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/weyl/

Or let's say that workable means conformity to your metaphysics. Fine, you haven't found technical and objective treatments that agree with your non-technical home-brewed metaphysics. But have you really shopped around?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smooth_infinitesimal_analysis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constructive_analysis

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computable_analysis

I'm not sure how such options can be intelligible in the first place to someone who hasn't learned at least the basics of mainstream real analysis. Or at the very least a semi-rigorous calculus. As far as I can tell from your posts, you think that math is some strange form of metaphysics that uses symbols as abbreviations for fuzzy concepts. And then proofs are just fuzzy arguments to be interpreted like mystical literature on the profundities of time, space, matter. Not so. The black queen on a chess board rules no kingdom. Legal moves are strictly defined and computer checkable. While the queen piece may be called a 'queen' and not a 'pawn' because of her exquisite mobility, what we call her and the intuition associated with that name is not important to the computer that checks whether a move is legal. It's only her place within the structure that matters. Math has to be this 'dry' or machine-like for the vivid objectivity it has in contrast to vague qualms about 'actual infinity' or the 'continuum.'

*I'll extend this point to metaphysics in general by quoting Wittgenstein. What I mean by it in this context is that none of us even have access to what is 'meant' by the 'continuum' or 'actual infinity.' For that matter even your private intuition corresponding to 'finite' cannot play a role. And so on. Only signs are public. In ordinary language, we have comparative freedom. In math no.

If I say of myself that it is only from my own case that I know what the word "pain" means - must I not say the same of other people too? And how can I generalize the one case so irresponsibly?

Now someone tells me that he knows what pain is only from his own case! --Suppose everyone had a box with something in it: we call it a "beetle". No one can look into anyone else's box, and everyone says he knows what a beetle is only by looking at his beetle. --Here it would be quite possible for everyone to have something different in his box. One might even imagine such a thing constantly changing. --But suppose the word "beetle" had a use in these people's language? --If so it would not be used as the name of a thing. The thing in the box has no place in the language-game at all; not even as a something: for the box might even be empty. --No, one can 'divide through' by the thing in the box; it cancels out, whatever it is.

That is to say: if we construe the grammar of the expression of sensation on the model of 'object and designation' the object drops out of consideration as irrelevant. — Wittgenstein

'The object [the continuum in our 'minds' or 'reality'] drops out of consideration as irrelevant.' -

What is knowledge?thoughts aren't 'made' of language, they're states of mind) — Bartricks

I'm trying to tell you that maybe you shouldn't take this old view for granted.

If I say of myself that it is only from my own case that I know what the word "pain" means - must I not say the same of other people too? And how can I generalize the one case so irresponsibly?

Now someone tells me that he knows what pain is only from his own case! --Suppose everyone had a box with something in it: we call it a "beetle". No one can look into anyone else's box, and everyone says he knows what a beetle is only by looking at his beetle. --Here it would be quite possible for everyone to have something different in his box. One might even imagine such a thing constantly changing. --But suppose the word "beetle" had a use in these people's language? --If so it would not be used as the name of a thing. The thing in the box has no place in the language-game at all; not even as a something: for the box might even be empty. --No, one can 'divide through' by the thing in the box; it cancels out, whatever it is.

That is to say: if we construe the grammar of the expression of sensation on the model of 'object and designation' the object drops out of consideration as irrelevant. — Wittgenstein

Apply this to 'knowledge.' We learn how to use it as children. We don't know the 'states of mind' of others as we do so. As long we our behavior conforms to largely tacit norms, all is well. We 'know English,' without ever having direct access to others' minds. This applies not only to knowledge but the words 'mind' and 'matter' also. This situation suggests that we look for 'meaning' in the way that the signifier 'knowledge' is traded between us in the total context of our lives, including actions. Meaning is 'outside the mind' and 'between' us. The 'beetle in the box' is inaccessible by definition and cannot play a role.

What start? — Bartricks

All the stuff you didn't quote and respond to. If you don't understand something, then please ask for clarification. Pretending that I didn't go to any effort is silly.

So I have to read Hegel now?! — Bartricks

I'll give you some useful pieces of Hegel for this situation.

Science lays before us the morphogenetic process of this cultural development in all its detailed fullness and necessity, and at the same time shows it to be something that has already sunk into the mind as a moment of its being and become a possession of mind. The goal to be reached is the mind’s insight into what knowing is. Impatience asks for the impossible, wants to reach the goal without the means of getting there.

...

What is “familiarly known” is not properly known, just for the reason that it is “familiar”. When engaged in the process of knowing, it is the commonest form of self-deception, and a deception of other people as well, to assume something to be familiar, and give assent to it on that very account. Knowledge of that sort, with all its talk, never gets from the spot, but has no idea that this is the case. Subject and object, and so on, God, nature, understanding, sensibility, etc., are uncritically presupposed as familiar and something valid, and become fixed points from which to start and to which to return. The process of knowing flits between these secure points, and in consequence goes on merely along the surface. Apprehending and proving consist similarly in seeing whether every one finds what is said corresponding to his idea too, whether it is familiar and seems to him so and so or not. — Hegel

The case is this: norms of reason exist (so, prescriptions, demands, that kind of thing). Only a subject can issue a prescription. Therefore norms of reason are the prescriptions of a subject - Reason. — Bartricks

If you grasp the 'beetle in the box' point, then you should see that the most important norms, those of intelligibility itself, exist between 'subjects.' I can never know if we both 'see red' in the same way, nor whether our 'private intuitions' of the 'meaning' of knowledge are congruent. All we can do is trade signs within conventional/'exterior'/'material' 'norms of intelligibility.'

The way we can (roughly) make sense of your 'Reason' as a subject is think of our shared practices as a kind of foundation of the 'private subject.' To enter a language is incorporate the norms of a community and be trained to 'make sense of' that culture's signs (including things like turn signals and handshakes.) In that sense we are 'Reason' and also individuals who contribute to the invention of new signs and the transformation of the norms governing the signs we started with.

Last comment: lots of what I'd call illusions about language are generated by working with toy examples. A strong theory has to make sense of its own possibility and explain the meaning-effects of the most advanced philosophy --or at least not ignore them. Or consider this infinitely suggestive passage from the end of Finnegans Wake.

https://www.trentu.ca/faculty/jjoyce/fw-627.htm -

Infinite worldWere those guys all living about the same time in Germany? Similar philosophical bents? — DanielP

Hegel and Feuerbach came earlier. Feuerbach is largely remembered as the bridge between Hegel and Marx, but I think he's underrated. Wittgenstein and Heidegger were early 20th century greats. What connects all of them is their understanding of how social and historical we are as human beings. We aren't trapped in our heads like pieces of 'mind' mysteriously stapled to pieces of 'matter.' Or, at the very least, they show where this initially plausible framing of the situation goes wrong and is no longer illuminating but in fact conceals what makes that framing possible in the first place, what I playfully call 'softwhere.' (I've been reading John Gordon's book on Finnegans Wake. ) -

Infinite worldThat's the enjoyment of philosophy, to take some basic assumptions, and then test them out. See where they play out, even if not conventional.

Philosophy asks questions like where did we come from, where are we going, what is our purpose within the cosmos? Even if someone is way out there, it is still interesting to discuss. — DanielP

Well put. And, for what it's worth, I think that philosophy makes and has made progress. 'Know thyself' can be understood as directed at the 'global' subject, by which I mean humanity as the protagonist of history, and that history as a self-creation that is also humanity's self-consciousness. In time we come to know ourselves as time. But that's just one story, one conversation among all the possibilities you hint at.

When did you get interested in philosophy? — DanielP

I guess I was about 16, which makes for 20+ years of studying it. A conversation that stretches over centuries comes slowly into focus, neither religion nor science but scratching both kinds of itches at once. -

Infinite worldIf he was deaf AND raised by wolves I doubt very much he’d ever have stood a chance of acquiring language so late in his life. The key element of language being ‘common experience’ and a ‘common social environment’, rather than ‘word symbols’ (be the auditory or visual). — I like sushi

Yes, this makes sense to me. At the same time, I think symbols are necessary for conceptual sophistication. I'm guessing that some primitive unformalized language of gesture would be hard to avoid. -

What is knowledge?But I made a case for my view, and once more you are merely reporting that there is some mysterious counter-case. Why not make that case? — Bartricks

I think this forum is great for discussing our readings away from this forum, but I don't at all think that online debate is a substitute for that reading. I recommend looking into Wittgenstein (Philosophical Investigations). Recently I discovered this short text, highly recommended: http://www.colby.edu/music/nuss/mu254/articles/Culler.pdf

As as general opening, this short video is great: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x86hLtOkou8

The 'big idea' is that meaning isn't located 'inside' the individual 'mind.' Language is radically social and embodied. Human reason is a social and not an essentially private phenomenon, despite an obsolete philosophical tradition to the contrary. Descartes writes the following.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pineal-gland/#DescViewPineGlanThe first [rule of thought] was never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such; that is to say, carefully to avoid precipitancy and prejudice, and to comprise nothing more in my judgement than what was presented to my mind so clearly and distinctly as to exclude all ground of doubt. — Descartes

What is neglected in such a principle is the nature or way-of-being of this 'I' and this stuff, language, that thought is made of. Also accepted is the background idea of a mind-stuff connected to extended matter (perhaps through the pineal gland,) a theoretical prejudice taken for granted.

There is much more to the case against language as a nomenclature for mind-stuff essences, but this is a start.

As for why 'Reason' has a capital R, it is both in order to distinguish Reason - the source of the norms of reason - from the faculty, 'reason' that we use to detect those norms, and from 'reasons' which are the directives constitutive of the norms themselves. So, reasons are norms, norms have a source - Reason - and we have faculties of reason by means of which we detect them. — Bartricks

What's the case for this source of norms? If you look into thinkers like Hegel, you'll find the idea of cultural evolution, where ethical norms and the norms of intelligibly are unstable. To postulate to some fixed, definite source looks like a rigid and unjustified theology. That reason is a (post-)theological concept is something I'd assent to, and indeed I've written about that in the 'What God is Not' thread. But, importantly, reason (our notion of it) evolves as we reason. In that sense, philosophy is the conversation through which reason attains 'self-consciousness.' This 'self' of reason is necessarily social, a 'we' rather than an 'I.' The case for this is related to the the one provided above.

In my view, the 'case' is not conceptually but only emotionally difficult. If we are profoundly social and historical beings, then we radically depend on our inheritance. Along with this comes the staggering difficultly of saying something new and important and 'starting from zero.' The 'individual' primarily has value and interest as an intellect through the assimilation of what has already been thought, an assimilation that merely continues the learning of a language. Our vanity whispers to us that we are geniuses who don't depend on the centuries of thinking now concentrated for accelerated digestion in a philosophical tradition.

There is patently a difference between simply believing something is true and knowing something (it is implausible that it is just some arbitrary linguistic convention) — Bartricks

That the siginifier is arbitrary is well established. But I understand that we have what we call 'intuitions' and 'mental experience.' So it's really just an issue of seeing how thoroughly permeated these intuitions are with social conventions. Indeed, only social conventions make talking about them possible. What I'm getting at is not the denial of meaning but a holistic conception of meaning that sees it as part of a entire 'form of life.' I don't claim to have originated any of the thoughts I've presented here. I've just digested some greater thinkers (which one is never done digesting) and am trying to share what I understand so far. -

What God is not

Perhaps there's a clue, found in a previous post.This still just leaves me wondering what the heck you actually believe that is actually different from what an atheist believes, not just nominally. — Pfhorrest

However an interesting dialogue may be had between Christian humanists who posit that God is bound within language and does not exist beyond it (e.g. Don Cupitt) and Tillich who posits that our understanding of God is bound within language yet presumes (but cannot verify) that God exists beyond it. — Wayfarer's post in Tillich

To me the 'realm of meaning' which includes noetic objects like 7 is related to the 'ideality of the literary object.' I think this realm as it wanders from simple math depends on material for signifiers, but nevermind that. It seems that people can have an I-thou relationship with an 'ideal' or 'noetic' God who isn't physically there. I sometimes feel a bond to writers of texts I love, long dead. Don't we live in a world of such ghosts? Imagine how we should have continued conversations? Interact with people from our childhood, long lost, in dreams?

As something like a 'Christian humanist,' I'm happy with the ghost as a ghost (the 'Holy Spirit'). This spirit passes to and fro a community of saints (sinners who forgive one another). Others are concerned perhaps with justifying the possibility of a God that exists beyond language and such community, by which I understand beyond the ideality of the literary object or field of shared meaning and feeling. Within this realm of meaning, within language and culture, we can gesture beyond to a more metaphysical God. Perhaps being itself is God. Or all being is the 'incarnation' or representation of God.

If God is a noetic object, that more or less seems to make sense to everyone. If God is (or refers to) the ground of being (being itself perhaps), that also makes a certain sense. But God as ground of being seems to open the problem of evil and/or shift us into Job's meeting with the whirlwind. Perhaps this is the 'God of God.' Personally the metaphysical issue seems less important than the divine predicates, which only make sense to me as human virtues. One can cast an amoral Father as a demiurge in the whirlwind and a tender (mother and) son who restores the loss. -

Infinite world

I found this.

https://www.nytimes.com/1991/02/03/books/all-language-was-foreign.html

Fascinating! Thanks.

A human being without language would seem to be a 19th-century phenomenon; at least that's what people tried to tell Susan Schaller. But one day in the late 1970's Ms. Schaller, while working as a sign-language interpreter in Los Angeles, encountered a 27-year-old deaf Mexican man who seemed bright and curious but who, as she quickly discovered, had no language whatsoever. No sign language, no written or spoken Spanish or English. The man, whom the author calls Ildefonso (a pseudonym), was an illegal alien who had worked at a variety of jobs all over the United States but had somehow managed to get by without knowing how to add or subtract or even how to tell time.

Ms. Schaller, fascinated, was determined to make linguistic contact with him. She succeeded; the man suddenly connected "cat" -- the picture, the sign and the written word. And he was hungry for more. For her, Ildefonso's breakthrough was every bit as exciting as Helen Keller's discovery of water at the well.

In essence Ms. Schaller's book, "A Man Without Words," is a meditation on the wonders of language. Without language, there is no way to understand the passage of time. Ildefonso had no idea what a birthday was. In order to get to work on time he memorized how the face of the clock looked. Ms. Schaller began to realize how crucial language is in the organization of our inner selves, how it influences our perceptions about the world. To teach adjectives, the author began with colors. When she hit the color green Ildefonso was horrified. Eventually Ms. Schaller realized that, for Ildefonso, green represented the immigration officials who frequently captured him -- the color of their trucks and uniforms, even the green card he didn't have. Without language, the color came to symbolize all that was frightening. Without some language system, some explanation, history and geography cannot be comprehended unless one has lived every moment in time and traveled every foot of ground. There isn't even a way to illuminate the concepts of deafness and hearing.

Seven years later, Ms. Schaller tried to re-establish contact with her student. Convinced his was not a unique case, she searched for others like him as well. She discovered that several teachers had worked with deaf people who had no language, many of whom were from different cultures or who had astonishingly protective parents. She also pored over studies of so-called wild children, consulted treatises on language such as "The Man With the Shattered World" by A. R. Luria, and talked to the physician and writer Oliver Sacks, who urged her to continue her pursuit, and who ultimately wrote the foreword to this book.

When Ms. Schaller finally finds Ildefonso, he is working as a gardener for a hospital in Los Angeles and the proud holder of a green card. His gardens are characterized by order and symmetry. He is an eager student, and his signing has advanced by light years. He tells the author he now tries to find people to interpret the evening news for him. And he has developed a philosophical bent from all those years of observing: "There is enough in the world for everyone to have a little garden," Ildefonso tells Schaller. "Everyone could be content. But some people want gigantic houses and gigantic gardens, so they fight and steal and buy up all the land and others can't have anything."

Over dinner, Ildefonso tries to demonstrate how people without language communicate -- he has a younger brother, deaf, also without language. He wants to show the author what his life was like before the miracle of language, but he is incapable of regressing to his previous state. And so he takes her through back alleys to a tiny room where she discovers a virtual lost tribe: people who have no language.

No one has a name here; introductions are really descriptions. And each person has peculiar ideas about cause and effect in life. One has discovered that the number 1986 seems to satisfy authorities and believes that those shapes are endowed with magic. But as the people tell stories, it can only be done through mime, each movement an invention. One person might repeat a gesture but, as Ms. Schaller realizes, most communication is trial and error. She witnesses a testament to how slow and painful the evolution of language must have been. — article -

What is knowledge?What matters is the quality of the case, not its mere existence. — Bartricks

I agree. To be more blunt, strong cases have been made (later Wittgenstein, for instance) against thinking that knowledge is something definite like an attitude of 'Reason.' And what does the capitalization add? It suggests that 'Reason' is a kind of divinity. As I've written in other posts, there's some historical truth in that. But it's dicey in this context, is it not?

Where have I said that there is an 'entity' called 'knowledge' (I am arguing that there is not)? — Bartricks

You define knowledge as an 'attitude,' an entity, 'a thing with distinct and independent existence.' Knowledge is something definite, you write, an attitude taken by (personified) Reason.

Rather, they're just fiddling with Gettier cases — Bartricks

If you look at my posts in this thread, I started to sketch a different approach, along the lines of Wittgenstein. Roughly speaking, language is just one part of a form of life that depends on conventions that are mostly inexplicit. In the real world we use lots of words together, in particular context. Language is not primarily a nomenclature, a code-book referring to independent/atomic concepts.

As philosophers we are tempted to use our intuitions to invent essences for nouns taken out of context. So we play the game of 'knowledge is really X,' as if we could legislate for a living language.

It's a nice game, and perhaps there's value in it. But perhaps there's also value in grasping its limitations and assumptions consciously. -

Infinite worldYes. That’s kinda the problem. — I like sushi

Even a rough sketch might help me locate what you're getting at. I do think that there's no clean separation of word from deed. Much of our language use is as automatic as animal noises. -

Infinite worldThe problem is how this fits in with everything else he says in terms of ‘Dasein’. It’s contrary and I suspect he was quite purposeful in how he was trying to hoodwink the reader. — I like sushi

I've had a love-hate relationship with Heidegger for years. I'd write him off and yet be pulled back.

For me a decisive moment was reading translators of Heidegger whose English I liked: Theodore Kisiel, John Van Buren, and William McNeill.

William McNeill translated the short lecture version of The Concept of Time. As you may know, this is sometimes called the 'ur-B&T.' In 22 pages the basic ideas are laid out, in a prose that verges on poetry. Then Kisiel wrote The Genesis of Being and Time, tracing its development through Heidegger's earlier lecture courses and quoting letters, also translating History of the Concept of Time, which is close in content to B&T (as you may well know already.) Van Buren translated Ontology: Hermeneutics of Facticity. This is nice because it's short, of similar intensity throughout, and shows Heidegger's terminology still in development -- but still working on the same themes.

Huge lumps of text he wrote in B&T were frustratingly pointless. I don’t trust writers if they lead you on a merry dance to say something that could’ve been summed up in a couple of paragraphs. That said, it is forgivable on occasion, but when 80% of the entire text needn’t be there I’m not impressed. — I like sushi

I still haven't read all of B&T. I was also disgusted by those chunks. I may never decode some of them. But then the chapters that do make sense to me are IMO as good as it gets in philosophy. Even if I can find only 300 pages of Heidegger that I'd be brave enough to paraphrase, those 300 pages are golden. The longwindedness of B&T may be related to him being forced to squirt something out to get a job. The earlier parts seem 'mastered' and to have come naturally. Maybe the rest was more of an improvisation, a work-in-progress.

Derrida is an even worse culprit, but at least he pretty much admitted what he was doing so I can forgive that — I like sushi

Derrida can indeed be a pain, but Limited Inc is a work that stands out to me for its clarity. What first got me truly interested in Derrida was his treatment of Saussure as presented by Bennington in Derrida. Recently I discovered Jonathan Culler, a refreshingly focused writer. Not only did he write a great book on Saussure, he also wrote on Limited Inc.

http://www.colby.edu/music/nuss/mu254/articles/Culler.pdf

I love Derrida for the concept of iterablity and all that it implies. Not only that, but that was my path in. He is sometimes too indulgently artsy for my taste. But I tolerate it. Reading his biography lately (by Peeters) was illuminating. He gave Sartre hell, but I think he connects to some key passages in Nausea. I see him as truly fascinating by the wonder and depth of what it means to write and read.

Heidegger was merely playing at rewriting Husserl’s ideas (likely because he assumed Husserl’s work would be buried and forgotten). — I like sushi

It's my understanding that Husserl didn't approve of Heidegger's work, and not because it was theft. Indeed, in the introduction to Crisis, the translator David Carr stresses that addressing historicity was a deviation from Husserl's past work (which I have only experienced through secondary sources.)

The question of historical genesis is explicitly banned from phenomenology per se in Husserl's writings up through the Cartesian Meditations. Yet in the Crisis it suddenly makes its appearance as something the author obviously thinks is important. — Carr, page xxxv

There is ‘language’ beyond mere ‘worded language’. It is frankly foolish to ignore this. That is not at all to say that ‘worded language’ is hugely important - or how else would we be communicating now! — I like sushi

Could you elaborate on this? -

Infinite worldI've always been interested in the biggest picture possible. — DanielP

That's what I love about philosophy. It goes for the biggest picture and also the deepest picture.

I think that yes, it may seem there are boundaries between things, and yes these boundaries may seem important in making sense of things. But I think those boundaries are temporary and ultimately fade away in a sense over time. — DanielP

The map of the boundaries of human civilizations has changed so much that it is unrecognizable over a thousand year time span. — DanielP

I agree, and some of my favorite philosophers are focused on time, on the way our 'maps' or human structuring of the 'territory' evolved and evolve historically, basically like a long human conversation. Our individual bodies die, but our stored knowledge and accumulated transformation of the earth means that each generation inherits what all preceding generations left behind (well, what wasn't destroyed or lost.) To me this indicates increasing complexity in the conversation, which is ecstatic if we can bear it. And if we can find the time and will to assimilate it.

This Hegel quote talks about what I meant by 'deepest' picture possible.

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/ph/phprefac.htmWhat is “familiarly known” is not properly known, just for the reason that it is “familiar”. When engaged in the process of knowing, it is the commonest form of self-deception, and a deception of other people as well, to assume something to be familiar, and give assent to it on that very account. Knowledge of that sort, with all its talk, never gets from the spot, but has no idea that this is the case. Subject and object, and so on, God, nature, understanding, sensibility, etc., are uncritically presupposed as familiar and something valid, and become fixed points from which to start and to which to return. The process of knowing flits between these secure points, and in consequence goes on merely along the surface. — Hegel

To me philosophy at its best is the opposite of merely going along on the surface of things, which is our ordinary mode in daily life. Of course we have bills to pay, but for me one of the reasons to keep those bills paid, etc., is to be able to live & think philosophy. -

It's All Gap: Science offers no support for scientific materialismI'll need some time to work through it. It may be a few days before I give a full response, as this is a busy time with family and (I'll use your word here) community. — GeorgeTheThird

Sure. Understood. I'll just reply a couple of points you made. Respond when you have time. I happen to have lots of free time lately.

In many respects, we share a common set of values. You speak of kindness, justice, honor, freedom; of ideals and goodness. We are, as you might put it, connected as human beings, our fundamental philosophical differences notwithstanding. — GeorgeTheThird

Right. So there's some kind of gut-level openness and empathy 'beneath' all the theory. Hume wrote well on this.

Yet this particular difference matters a great deal, because of its implications: I consider that true goodness must be something more than a shared favorable opinion. A good act must be good, and a bad act bad, in and of itself, regardless of whether I like it or not. Otherwise, on what basis do we heap reproach on the Nazis, who believed they were doing humanity a favor by ridding the earth of the Jews? On what basis do I restrain myself today from rationalizing an act which six months ago I condemned as treachery? On what basis do we punish people with loss of property and freedom when they violate the community consensus of good behavior? — GeorgeTheThird

This is a deep issue, not easily answered. But I'll try to sketch the problems with morality being absolute and fixed. Unless we feel in our hearts that the Law is just, we have to experience the Lawgiver as a tyrant. We'd also presumably be back in the wars of religion. Even if everyone accepts the existence of a Law and Lawgiver, there's still disagreement about who gets to be His Voice on earth. If we accept Christianity, for instance, which texts are relevant and how are they to be interpreted? Literally, metaphorically, speculatively? So from my point of view we as human beings are just stuck with having-to-interpret, with the angst and ambiguity of existence. We are the 'thrown open space' of/for endless interpretation, constantly thinking of our pasts differently as we entertain new possibilities for our futures. In this sense we 'are' time as

interpretation.

I do sympathize with the desire to escape from history and time into something eternal & solid. Capitalism is a permanent revolution that we just take for granted now. It strips away all the old sacred things and turns us all into commodities. And the world is changing too quickly for any of us to understand more than a fraction of it. A runaway machine. So perhaps all philosophy (inasmuch as it tries to replace religion) seeks some kind of structure or stillness in the noise and chaos. God is a king above all disaster, and the sage is a God-man. If history is a nightmare from which we are trying to awake, then the dream of a perfect philosophy is of that awakening, of being a king outside of time and space. Neo sees the code behind the chaos. -

What God is notI wonder if you'd be willing to offer a reference or exposition. — ZzzoneiroCosm

I highly recommend A Thing of This World by Lee Braver. It weaves Heidegger into narrative that stretches from Kant to Derrida. I read it for free as a pdf and then bought the paperback.This is review by another book by Braver, relevant to the history of being.

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2014/05/18/book-review-heidegger-thinking-of-being-by-lee-braver/In the chapter ‘History, Nazism, the History of Being and its Forgetting’ Braver argues that Heidegger, in his later writings, emphasizes the history of being rather than pursuing explication of existential phenomenology. He provides a short history of being, divided into four separate parts: pre-Socratics, Platonic, medieval, and modernity, with each area having its own unique understanding of being. Accordingly, human beings’ way of being alters throughout history, due to an ontological understanding of being that shapes a culture’s entire way of acting and thinking. Braver, in Groundless Grounds (2012, p.117), wrote that “Only Greeks can be tragic heroes, only Medievals pure-hearted saints, and only moderns comfort-seeking gadget-users”. He pursues this idea in the book while claiming “And our way of being changes with them so that a Greek citizen, a medieval monk, an early modern gentleman-scientist, and a modern iPhone user are different kinds of subjects” — review

In my own words, the 'I' is only possible on the foundation or background of 'we.' One uses a word this way. A road is for driving on. A sidewalk is for walking on. Time is money. For instance, 'I' think about 'myself' in a language I did not create and starting from 'values' (still too abstract and theoretical) that I did not choose. We are 'thrown' into our cultures way of living and thinking, and of course into having particular parents. If we rebel and want to bring down the house, we use pieces of that house. We use an inherited language to for instance try to transcend that language or see around it. I think lots of Heidegger and Hegel are contained in Joyce's/Stephen's 'history is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.' For Hegel, we dream toward an awakening. For Heidegger it's less clear, though in one interpretation there's no structure, no telos, just various unfoldings, clearings. Which aren't in our control. For if we could choose, we'd choose in terms of our thrown-ness. For the later Heidegger, there is an irreducible passivity in human existence, which the technological interpretation of being covers up. So Nietzsche is the last metaphysician. Platonism rots into pragmatism and will-to-power as a late manifestation of being (what counts as real & significant).

The fantasy of not-being-thrown is connected in my mind to a god independent of nature and especially time and philosophy's lust to be without presuppositions, its own father, to have given itself its own name. Man is time trying to crawl out of itself. (?)

The quotes below described being within what I'm calling (got it from Braver?) an 'understanding of being.' The quotes on 'the nothing' remind me of Feuerbach. These connect to our larger conversation about God.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/heidegger/#HisHisThe history of Being is now conceived as a series of appropriating events in which the different dimensions of human sense-making—the religious, political, philosophical (and so on) dimensions that define the culturally conditioned epochs of human history—are transformed. Each such transformation is a revolution in human patterns of intelligibility, so what is appropriated in the event is Dasein and thus the human capacity for taking-as (see e.g., Contributions 271: 343). Once appropriated in this way, Dasein operates according to a specific set of established sense-making practices and structures.

...

Where one dwells is where one is at home, where one has a place. This sense of place is what grounds Heidegger's existential notion of spatiality, as developed in the later philosophy (see Malpas 2006). In dwelling, then, Dasein is located within a set of sense-making practices and structures with which it is familiar. This way of unravelling the phenomenon of dwelling enables us to see more clearly—and more concretely—what is meant by the idea of Being as event/appropriation. Being is an event in that it takes (appropriates) place (where one is at home, one's sense-making practices and structures) (cf. Polt 1999 148).

...

Even though the world always opens up as meaningful in a particular way to any individual human being as a result of the specific heritage into which he or she has been enculturated, there are of course a vast number of alternative fields of intelligibility ‘out there’ that would be available to each of us, if only we could gain access to them by becoming simultaneously embedded in different heritages. But Heidegger's account of human existence means that any such parallel embedding is ruled out, so the plenitude of alternative fields of intelligibility must remain a mystery to us.

...

Because the mystery is unintelligible, it is the nothing (no-thing). It is nonetheless a positive ontological phenomenon—a necessary feature of the essential unfolding of Being. — link

I think of this 'nothing' as what makes poets the 'unacknowledged legislators of the world.' It's a pregnant darkness. People like Descartes see the world in a new way. Later we take what was visionary for granted. Another Heideggerian theme is restoring force to the most elemental words, which I understand as rediscovering the radicality of metaphors that have cooled and hardened into common sense.

I offer all of this humbly. I just love this stuff and enjoy trying to make sense of it with others. -

What time is notWell the concept of 'measure', as alluded to above by softwhere, seems to be math's answer. But measure theory does not seem (from my very limited knowledge of it - ?) to provide a justification for treating a point as dimensionless (or that there are infinite points on a line segment). — Devans99

The important thing to grasp is that math doesn't ultimately work with mere intuitions of what a point 'really' is. Such intuitions can guide the construction of a formal system, but the math itself is a definite formal system. That's why serious finitists and contructivists offer new exact systems. If it isn't a system that's as a dead and machinelike and trustworthy as the rules of chess, then (roughly) it isn't math. Because then it isn't a 'normal discourse.'

This is why a person has to learn to read and write actual mathematical proofs to really know what math is. So I encourage you to get a book on proof writing and reading. It will be fascinating, and your criticism will have more relevance. -

What God is notThis is the thrust of a book I hope to put together before I'm cozy in my coffin. Instead of "magic," I like to say "mystique." Mystique and Nothingness.

I have a load of research ahead of me. But say you have the world-mystique of the Middle Ages and the loss of world-mystique concurrent with the loss of Christ or death of god. The billboards exploit the loss of world-mystique. Political figures exploit the loss of world-mystique. Etc. — ZzzoneiroCosm

Nicely put. These are also themes I'm interested in. Mystique and Nothingness would be the kind of philosophy I like. Great project.

I think the transformation of world-mystique is what Heidegger had in mind in terms of the understanding of being. 'If it's gear, it's here', 'If it spends, we're friends.' 'If it get clicks, it sticks.' What does a culture take as real, true, valuable, authoritative? Have you seen Debord's film? If you get in the mood, here's a link: https://vimeo.com/139772287

In Nausea I see the intimate link between mystic union and schizophrenia. Joseph Campbell writes: "The schizophrenic is drowning in the same waters in which the mystic swims with delight." — ZzzoneiroCosm

I read The Masks of God recently and was quite impressed. Anyway, that quote makes sense. The shaman is perhaps the survivor of a schizophrenic crisis. -

Infinite world

Well I can try to explain what I find valuable. But I don't read German. For me studying Heidegger further illuminated Hegel and Feuerbach and Wittgenstein. Then Culler's book on Saussure fits in too. I just read that one and it further illuminate Derrida (the 'perfected Heidegger' some have said.)We’ll have to at it over Heidegger sometime. — I like sushi

(a few selective quotes from previous works would be nice regarding ‘dasein’ if you can manage it? — I like sushi

Heidegger is already using 'Dasein' in Ontology, which I have on hand, but doesn't offer a definition, probably because it's a common German word, which he is further specifying through context and what he does with it. To escape bias, I'll just use a German-English dictionary.

https://www.dict.cc/german-english/Dasein.html

It means 'to be there' or 'to be around.' I think that Heidegger was just trying to get around an encrusted tradition and talk about the 'subject' or the 'rational animal' with fresh eyes.

I'm sure you've seen this in B&T, but it's at least Heidegger being explicit.

This being, which we ourselves in each case are and which includes inquiry among the possibilities of its being, we formulate terminologically as Dasein. — Heidegger / Stambough translation, top of page 7

Since the who of everyday Dasein is 'one' rather than 'I,' I think it was a good move. To me the philosophical prejudice that we are isolated subjects in a mind-box was a primary target of the analytic.

The 'beetle in a box' point made by Wittgenstein seems to get at the same kind of thing. What we are tempted to take as a hidden interior is primarily exterior. Pinkard's book on Hegel's POS (The Sociality of Reason) presents Hegel in something like today's terminology, and seems related. I chose the name 'softwhere' for this primary object of fascination for me, the way we exist culturally, more we than I[, largely in language but also through music, etc.

He missed that the words coming out his mouth were an expression of values though, he was seemingly unaware of the force a narrative has for carrying ‘emotional’/‘moral’ weight. — I like sushi

Ah, I see. I'm am very much with you on 'the force of narrative.' I think we humans qua human exist on that level, on the level of the ideality of the literary object, some of which are the instrumental (non-)fictions of science. The scientific image is grounded in the manifest image and yet aims at the ground of the manifest image. -

What God is notThanks. I bumped into Eckhart by way of Derrida. I forget the name of the book. — ZzzoneiroCosm

I bumped into Eckhart in Caputo's book on Heidegger. Also Angelus Silesius.

The Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition identifies these epigrams as Reimsprüche—or rhymed distichs—and describes them as:

...embodying a strange mystical pantheism drawn mainly from the writings of Jakob Böhme and his followers. Silesius delighted specially in the subtle paradoxes of mysticism. The essence of God, for instance, he held to be love; God, he said, can love nothing inferior to himself; but he cannot be an object of love to himself without going out, so to speak, of himself, without manifesting his infinity in a finite form; in other words, by becoming man. God and man are therefore essentially one.[9] — Wiki

I think this is what Hegel wanted to rationalize.

Also this:

The rose is without 'why'; it blooms simply because it blooms. It pays no attention to itself, nor does it ask whether anyone sees it. — Angelus

This reminds me of Wittgenstein: It's not how but that the world is that is the mystical. Such an insight is repeated in Nausea, albeit in its unsettling aspect. -

What God is not

I like the poem. It reminds me of Whitman, and I love Whitman.

I'm not sure there's anything like a permanent escape from (let's say) "everydayness." After all, as they say, samsara is nirvana.

Meditative practice has a permanent effect on brain wave patterns. That might be the best we can do. — ZzzoneiroCosm

That's how I tend to view it. There is no enduring escape, but moments of insight and ecstasy leave traces on everyday living. And I love my favorite philosophers for unveiling what is profound in the apparently mundane. There's a 'spiritual' ambition or intention in the great philosophers that is bigger and brighter than technology-as-truth ('If it's gear, it's hear.', 'If it's useless, it's unreal.') As you may know, Derrida's first paper was on the 'ideality of the literary object,' which is arguably the 'spiritual realm,' our intersubjective participation in the 'holy spirit' of language. This embarrasses the tough-minded pragmatist who sides ultimately with worldly power against fleeting 'private' insights.

I also like God as the abyss of our unknown selves. I think that's what Feuerbach means by the species essence. As mortal beings in time, we can live out only a tiny part of our potential, of the species as still-unknown possibility (including paths that others take and we don't). And then I love the God in Job, a dark transrational or subrational God justified only by the beauty and terror of the real. In short, the idea of God or gods seems central to human existence. -

What God is notWith so many logicians skulking in cybershadows it's a mistake to resort to paradox. You won't be welcome and you won't be understood. — ZzzoneiroCosm

I tend to agree, I guess. I think theology should be rational or just confess itself as poetry.

The great poets - I think of Rimbaud's "genie" - come closest to describing god. But they fail. Great music can convey the moment of ecstatic union. But it's a dayfly shadow set beside the psych-ekstatic prowess of a devout and weathered mystic. — ZzzoneiroCosm

I enjoy this input. I know the ecstasy of music and rationalized theology, but I can't claim access to a mysticism that escaped a return to everyday life. I'm not familiar w/ the 'genie,' but I'll look into it. -

Human Nature : EssentialismThere is no denying that human psyche is variable and mutable, both on the historical and the individual human scale, but that doesn't make us blank states and empty vessels at birth, to be filled and shaped entirely by culture. — SophistiCat

I completely agree. I just emphasized (by exaggerating, let's say) the historicality and sociality of human existence. In this context, nature was being personified without irony or distance -without an awareness that 'Nature' as protagonist is one more piece of evolving culture. -

Information - The Meaning Of Life In a Nutshell?Apparently, some can only think milk. — Galuchat

Perhaps. But 'history is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.' People learn by talking as well as reading. That people on this forum vary in terms of exposure is clear. In some ways that's good. We are all forced to interpret the strange idiolects of (often enough) autodidacts. The posts I like best refer me to new thinkers.

Even the 'bad' posts are useful as opportunities for articulating what I think is wrong with them. I've been on and off such forums for years. While I learned more philosophy from books, I benefited from writing, writing, writing. I don't think there's a substitute for writing. It helps one see what, if anything, they have taken from their reading.

It's also a great place to observe and practice social skills. I read all kinds of threads that I don't participate in. To me the style of self-presentation is as interesting as the thoughts presented. Its part of a total projection through the public, written word of an ideal personality. -

Infinite worldI’ve not read much of Hegel yet. Started POS, but then my interested turned elsewhere. — I like sushi

I got into Hegel via Kojeve, translated by Allan Bloom. I thought the English prose was great, and it was Hegel from an atheistic point of view, influenced by Heidegger and Marx. I'll always love this book for blowing my mind. I haven't read every page of POS. I've learned quite a bit from secondary sources. And then the lectures he taught from are surprisingly clear. His theory of art is great, and there's a great Hegel In His Own Words biography that really impressed me. He could give rousing speeches, so clear, and yet write some very difficult prose.

but I still found use in B&T. — I like sushi

I like Division I, the basic examination of being-in-the-world. The death stuff is somewhat fascinating but suspect. I also like Ontology: The Hermeneutics of Facticity. And then Braver's work on the later Heidegger rescues it for me from some highly suspect prose. I do think that we're dominated perhaps by the spirit of technology. Though I don't see any easy path forward.

Maybe I wasn’t clear. I don’t ‘like’ any. I do admire Nietzsche for being a ‘non-philosopher’ and brutally honest, and Husserl for hesitating to call what he was doing ‘philosophy’. The rest, just the odd good scholar in between the Ancient peoples of the world, Descartes and Kant as far as I can see (which isn’t all that far). — I like sushi

Ah, thanks for clarifying. I've read Nietzsche pretty closely. He's such a glorious mess that figuring out what to make of him is like figuring out who one is in one's 20s (when I was especially taken by him.)

Husserl is fairly new to me. Derrida got me interested. Like many I've tried to cheat and work backwards. Rorty got me interested in Heidegger, Kojeve in Hegel, etc. You didn't mention Hume. No love for Hume?

Philosophers are just living black boxes. Once you pull them from the wreckage of humanity and look at what they regurgitate at you it’s often nothing much other than a bland drone of altitudes and bearings - with some caught in turbulence mistaking their view as ‘original’. — I like sushi

I think there's truth in what you say. But to me that's the human condition. Philosophers are like articulate especially maniacal types. What stand shall we take on our existence? What shall we spend our time talking about? I also love fiction, music, etc. But philosophy scratches the itch to make one's orientation explicit. A kind of suspect 'non-fiction' that is also 'obviously' just heroic roleplay. We carve little identities out of words. Politics looks to me like applied philosophy, including apolitical passivity and cynicism (which I preferred for most of my life and is still defensible, really.)

But all cynicism aside, I really love good conversation. The futility or absurdity of philosophy is more interesting topic for the philosopher.

Yeah, I can wax lyrical too, so what? That is still my point. What use is a nebulous statement for a meaningful discussion? May as well consult a random recipe braindead-ironic-neuroatheist style (referring to the dead-eyed intellectually empty mouth farts from a guy whose name thankfully evades me - even if he does make some sense some of the time). — I like sushi

I like 'mouth farts.' Zizek? Peterson? As Kant saw (not that I'm a Kant expert, but I like him), we just can't resist metaphysics. We are metaphorical-metaphysical-mythological animals. Bleed us of our dreams and there's nothing left. But Kardashians selling lipstick and becoming billionaires via social media fame. I've been studying Guy Debord lately, known for The Society of The Spectacle.

https://vimeo.com/60328678

I think philosophy often has a kind of negative glamour, like the sexy gloom of an existentialist. Sartre wrote somewhere that he wanted fame to get women. I won't accuse all philosophers of this, but perhaps there is a sexual display in the trans-scientific attitudes of various philosophers. The game is to project access to some difficult but valuable object. All one has to do is understand the magic words. At the same time, I think the 'magic words' often work, that one feels relatively illuminated. If all of this is illusion, then this too seems like a philosophical view, one that sides with power via technology.

It's complex, and I have mouth-farted too much already. -

Information - The Meaning Of Life In a Nutshell?Producing/consuming information makes our lives happier. The more information processed it seems the happier we get - we get excited by new information - neurotransmitters that raise our mood seem to be released during the production / consumption of information. — Devans99

I might use different words, but this roughly gets the joy of reading and writing right. A person should of course exercise and eat well, but beyond the obvious stuff I think endlessly challenging the mind (with interpretation and not just the absorption of facts) not only makes our lives happier but even feels 'essentially' human. And it's a clean form of pleasure: one is drunk on thought and not bourbon. One becomes capable of more kinds of conversation with more kinds of people. -

Davidson: "A Coherence Theory of Truth and Knowledge"In response to your question, I would argue that for Davidson beliefs are behavioral dispositions, as are skills....In your terminology, beliefs are skills. — quickly

OK, thanks. I've mostly read the continentals, though I had a long Rorty phase.

I'm glad you joined the forum. Your posts have been illuminating. -

What God is not

If God also exists, then God would be just another fact of the universe, relative to other existents and included in that fundamental dependency of relation. — Bishop Pierre Whalon

I think I understand this, and I think that's why various philosophers have more or less identified God with all of reality. To ensure that God remains good, reality has to be understood as either already good or on the way to becoming good, justified as a result. 'No finite thing has genuine being.' There is only God. Human consciousness is God knowing himself, etc.

There cannot be any empirical evidence of the existence of God, for God does not exist. — Bishop Pierre Whalon

Out of context, this looks suspicious. If God is not all of reality or a kind of shareable subjectivity, then in what way is s/he at all? To me it seems like the burden of a rational-philosophical theist to articulate how God is supposed to be or not be...basically what is intended. To be sure, a mystic need not reply to skeptics or offer explanations. -

Current Status of Rationalityt is also VERY important to consider that many cognitive neuroscientists seek funding by making somewhat misleading and fanciful claims simply because what they really wish to study is so banal finding the required funds to research is near impossible. — I like sushi

Food for thought. It's one of the annoying things about specialization. Who has time to keep up with it all? And scientists have to eat too. I have noticed lots of bad journalism abusing science, absurdly interpreting conclusions to generate clicks. Unfortunately all this muddy information just further encourages passivity coupled with fantasy. The machine runs on headlessly. -

Davidson: "A Coherence Theory of Truth and Knowledge"It is relevant to his argument that disagreement about specific facts can only occur against a background of shared true beliefs. — quickly

I like this, but skills is perhaps better than beliefs, in that 'beliefs' casts the whole thing as more explicit than I think it is. Have you looked into Dreyfus's Being-in-the-world? The 'form of life' is something like a set of norms that aren't explicit and can't plausibly be enumerated. -

What God is notGod can never be be evil or, to answer your question, God is not evil. — TheMadFool

Good answer. And that's because the divine predicates are familiar human virtues. Who made who? We created God in our own image, unconsciously, automatically. But what are concepts? They too are 'non-material' ghosts, like the concepts of the non-material and the material for that matter (which by the way threatens our conception of concepts.)

At the same time, God also works as a symbol for world entire in its mysterious presence. this whole vast circus is God, or entertainment for the gods. Lots of uses of 'God' and 'gods.' But the God of Christians only makes sense with human virtues, as a non-evil loving God. And yet, of course, what's with the hellfire? And that's how speculative philosophy is born, as an attempt to make theology rational. -

Infinite world‘Crisis’ is an incomplete mess. — I like sushi

But it's still good! It's like Husserl blended with Hegel and Heidegger.

I have certainly come across many who are far too willing to dismiss Husserl. I cannot blame them tbh as on the surface it looks quite dubious. It does require a certain fortitude to understand he is talking about self-made boundaries and limits, about the grounding of Logic, whilst being someone who sings the praise of ‘sciences’. — I like sushi

It's strange though that even a PhD in math is still suspicious when he gets philosophical. But I get it. I work in math, and lots of mathematicians are even anti-philosophical. But this leaves math and what it means hanging in the air. I suggest that the mystique of science (as opposed to squishy philosophy) primarily manifests our love of technology. 'If it ain't gear, it ain't here.'

I don’t think I could honestly say I ‘like’ any philosophers/philosophies. Some I find more interesting than others, but all-in-all I have more respect for those that do their best to articulate their findings and thoughts, so ‘philosophers’ rarely fall into that category tbh. There’s a glimpse in Husserl, but I’d hardly say he does much better or worse than any other. — I like sushi

I'm surprised you don't like more philosophers. I can understand frustrations with bad style, needless jargon, etc.

Today I’d call most philosophers either embittered individuals attempting to smuggle ideologies through under the guise of ‘philosophy’, or scholars of previous philosophers (the later I can respect if they temper their bias as much as impose their own will). — I like sushi

Is it smuggling though? I consider it the explicit projection of an ideology. I do think we are all biased and not as rational as we claim to be or would like to be. But that's why I like to think of an evolving conversation. I loved Lee Braver's A Thing of This World for organizing the tradition of anti-realism for presentation for an analytic-leaning audience. And this is why I love Hegel. He made this accumulative-dialectical-historical evolution of philosophy explicit.

Dead philosophers are also much easier to assess than living. The living do too much ‘talking’ and not enough ‘saying’. I think it is plain enough to see from entires on philosophy forums that a large contingent ‘attracted’ to this area of interest are generally trying to create a cult from themselves. Baby steps ... I prefer godhood ;) — I like sushi

I agree that philosophy types tend to be cult-leader types. I also prefer godhood. For me there's this complex idea that one becomes godlike by assimilating the genius of others. So the arrogant goal requires (strangely) a deep humility. This theme of vanity seems central to me. For me one of the marks of the wrong kind of arrogance (those mere baby steps) is not acknowledging how many of one's best ideas were stolen, inherited. The short-lived human being is nothing without the language he learned to speak and the conversations he's been a part of (often passively, as a reader.)

The cult-leader always has 'golden tablets,' freshly delivered by an angel --instant omniscience, just addwatera small donation. -

What God is not

While I understand where you are coming from, I also think the evolving idea of g/G has been and remains important. Why this monotheism? Why this God apart from nature? If Feuerbach was right, then God served a purpose as a stage of free and rational humanity becoming conscious of itself as such, a perhaps necessary error.

Not to invent, but to discover, “to unveil existence,” has been my sole object; to see correctly, my sole endeavour. It is not I, but religion that worships man, although religion, or rather theology, denies this; it is not I, an insignificant individual, but religion itself that says: God is man, man is God; it is not I, but religion that denies the God who is not man, but only an ens rationis, – since it makes God become man, and then constitutes this God, not distinguished from man, having a human form, human feelings, and human thoughts, the object of its worship and veneration. I have only found the key to the cipher of the Christian religion, only extricated its true meaning from the web of contradictions and delusions called theology; – but in doing so I have certainly committed a sacrilege. If therefore my work is negative, irreligious, atheistic, let it be remembered that atheism – at least in the sense of this work – is the secret of religion itself; that religion itself, not indeed on the surface, but fundamentally, not in intention or according to its own supposition, but in its heart, in its essence, believes in nothing else than the truth and divinity of human nature. — Feuerbach

God has the qualities of 'infinite' human reason-feeling-imagination distributed in fact over many mortal bodies--but concentrated and projected symbolically away from this plurality of local mortality. As human culture accumulates within language, a kind of super-mind is created that individuals can plug into by reading, thinking, living. God's omniscience functions as a point at infinity. The philosopher wants to know like God, from first principles. In short, God is an important 'fantasy' worth talking about. -

Human Nature : EssentialismEven for those who are not concerned about the laws of God, what about violating the laws of Nature? — Gnomon

How can one violate the laws of nature? I think you're framingnatureNature as another god. -

Human Nature : EssentialismRelative to the topic of this thread, Naturalism would find homosexuality to be, not only unnatural, but unethical. So, who's to say what's right : Darwin or God? — Gnomon

ThatnaturalismNaturalism (our demonic protagonist) would find homosexuality 'unnatural' is...absurd. Homosexuality has probably always been with us. And not only with us: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homosexual_behavior_in_animals

'Perversion' is created by the imposition of a norm. The norm and the perversion are created at the same time, like two sides of the same coin. No doubt primitive interpretations of nature have played a role in this. But this is comparable to social Darwinism.

the theory that individuals, groups, and peoples are subject to the same Darwinian laws of natural selection as plants and animals. Now largely discredited, social Darwinism was advocated by Herbert Spencer and others in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and was used to justify political conservatism, imperialism, and racism and to discourage intervention and reform. — dict

This can be read as a form of 'bad faith' and/or the rationalization of prejudice.

The thinking is perhaps that homosexual contact doesn't create offspring. Therefore (?!?!) it must be unnatural. [But whatever happens is natural, unless one believes in miracles.] And this crudely assumes that sexuality is a simple phenomenon that is only good for reproduction. It also crudely simplifies human sexuality. I recommend a The History of Sexuality (Foucault), not as an authority but as opening the space for thought. 'Heterosexuality' and 'homosexuality' are useful perhaps for rough categorization, but that's about it. The 'homosexual' is a kind of useful fiction, just like the 'heterosexual.' -

Information - The Meaning Of Life In a Nutshell?

I would just switch from information to interpretation. This is an active process. Metaphorically speaking, we are readers, readers, readers making sense of the text of experience, which includes actual texts and provides the metaphor.

This also allows us to make sense of existence-time or reading-time which is not physics time. As you read this sentence, it's beginning is dragged along in expectation toward its end. In reading there is no present, only the expectation of the future shaped from the past. I think we can generalize this to all of existence. Note also that the beginning of the sentence only gets a relatively settled meaning from the end of the sentence, so the (meaning of the) past is not fixed. In terms of the OP, 'interpretation' is less likely to come across as half-physics and half-philosophy in an unstable blend. -

Infinite worldI’m squishy like a peach with a stone at its centre: holding it together — I like sushi

I relate, if I understand you correctly. I love phenomenology. I fear that some will categorize it as mysticism, while the mystical-religious types might object that it still an 'atheism' that wants to be scientific in a high philosophical sense.

I believe you like Husserl. So do I. I recently read his Crisis and thought it was great. He's now on my list of favorites.

Thanks for the thumbs up. I like your way of putting it. -

Infinite world

I think this connects to one's conception of philosophy. Should it be poetic and/or 'spiritual'? Personally I think that it must be. We care about these things. And if we want philosophy to be quasi-scientific, then even that is a manifestation of our passion for objectivity, scientificity, practicality.

Hegel is one of my favorites, and he conceived of philosophy as doing conceptually what religion did imaginatively. I think there is truth in that. Feuerbach made it clearer, I think.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ludwig-feuerbach/That Feuerbach, unlike Strauss, never accepted Hegel’s characterization of Christianity as the consummate religion is clear from the contents of a letter he sent to Hegel along with his dissertation in 1828.[7] In this letter he identified the historical task remaining in the wake of Hegel’s philosophical achievement to be the establishment of the “sole sovereignty of reason” in a “kingdom of the Idea” that would inaugurate a new spiritual dispensation. Foreshadowing arguments put forward in his first book, Feuerbach went on in this letter to emphasize the need for

the I, the self in general, which especially since the beginning of the Christian era, has ruled the world and has thought of itself as the only spirit that exists at all [to be] cast down from its royal throne. (GW v. 17, Briefwechsel I (1817–1839), 103–08)

This, he proposed, would require prevailing ways of thinking about time, death, this world and the beyond, individuality, personhood and God to be radically transformed within and beyond the walls of academia.

Feuerbach made his first attempt to challenge prevailing ways of thinking about individuality in his inaugural dissertation, where he presented himself as a defender of speculative philosophy against those critics who claim that human reason is restricted to certain limits beyond which all inquiry is futile, and who accuse speculative philosophers of having transgressed these. This criticism, he argued, presupposes a conception of reason is a cognitive faculty of the individual thinking subject that is employed as an instrument for apprehending truths. He aimed to show that this view of the nature of reason is mistaken, that reason is one and the same in all thinking subjects, that it is universal and infinite, and that thinking (Denken) is not an activity performed by the individual, but rather by “the species” acting through the individual. “In thinking”, Feuerbach wrote, “I am bound together with, or rather, I am one with—indeed, I myself am—all human beings” (GW I:18).

In the introduction to Thoughts Feuerbach assumes the role of diagnostician of a spiritual malady by which he claims that modern moral subjects are afflicted. This malady, to which he does not give a name, but which he might have called either individualism or egoism, he takes to be the defining feature of the modern age insofar as this age conceives of “the single human individual for himself in his individuality […] as divine and infinite” (GTU 189/10). The principal symptom of this malady is the loss of “the perception [Anschauung] of the true totality, of oneness and life in one unity” (GTU 264/66). — link

Some might find this too squishy. My view is that certain philosophical problems are the result of taking the isolated ego as an unquestioned starting point. In an obsession with personal certainty, one neglects the being of the 'I,' which is mostly a we. For me it's not about hidden spiritual machinery but the naked-yet-taken-for-granted fact (however slippery) of being in a language together. I think it's hard to overstate how historical and social human existence is.

softwhere

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum