Comments

-

Avoiding costly personal legal issues in the West

-

Personal Identity and the AbyssConcepts do not exist - that is, they have no material reality. — Vera Mont

Interesting. This, to me, is to say that there are things that 'exist' and 'do not exist' yet they are all extant... Can you see if you can make the language there work? -

A quote from TarskianUntil you're willing to read the legal reports, keep beating hte horse my dude.

prostitution is persecuted only when it is deemed a disturbance to public order — Tarskian

I assume you got this from the legal reports about rates of prosecution? (btw, prosecution is the word you're looking for here).

If not, you'll need to provide those statistics (preferably vetted by an external HR-type source) for me to take this seriously.

You ahve also ignored hte direct challenges to your obvious hypocrisy and cherry-picking.

Are you going to address any of the objections you've received, or just continue to ignore them? I have asked specifically if you're going to beat a dead horse. Are you?

-

Is the real world fair and just?Given you find yourself alive, is it then better to have a positive or a negative mindset about that fact? — apokrisis

You'll need to let me know what this has to do with AN first (i can save the time: It does not have more than an aesthetic resemblance to the issues AN wants to deal with). In the meantime, I think I can address the question your asking, noting it is a non sequitur from defending/objecting to AN.

is your situation going to be made better or worse if you believe your fate is in your own hands, or if you instead believe the hope has already gone? — apokrisis

I don't think the question is that easy. Having one's fate in one's own hands seems to overwhelm (literally) the majority of people to psychosis.

I don't think any mindset 'ought'. That seems an extreme move to make. -

Is A Utopian Society Possible ?I said that a utopian vision depends on eliminating

wealthdisposition, skill and determination disparity — Vera Mont

Wealth may get us someway to equalizing these things, but they are not a good indicator at all. These problems will persist whether wealth even exists. Some will do, some will not do. That's the basis for the entire conversation, if one wants to think about it a bit further than 'wealth' which is a bit of a cop out when it comes to human behaviour. -

Avoiding costly personal legal issues in the WestLOL.

Oh brother. You don't understand the majority of what you've posted. I remember that zone well. -

The Liar Paradox - Is it even a valid statement?Which, based on the description above, it is not. This, unfortunately, would use some logic of language chat, which I have very little interest in.

Suffice it to say, it wants to say something it can't, and so contains no meaning. -

How 'Surreal' Are Ideas?Likely, but it might also be that he's collecting epistemic idealism under hte same banner - in which case, equivocally, his statement sort of hits.

-

The Liar Paradox - Is it even a valid statement?He's correct, as far as I can tell and am concerned at this stage. It is not a paradox.

-

Is the real world fair and just?You have to catastrophise the average life to make life itself seem always an intolerable burden and thus never justified in its starting. — apokrisis

You really, really do not. Your position is that of most people, even one's aware of hte burden of living so there are no surprises here. Just, not a lot of analysis. -

A quote from TarskianI present you with a simple fact, and you answer again with a useless word salad. — Tarskian

You did not. You posted a popular, sponsored article which has been removed from the 'credible' list by more than one poster. You're going to beat a dead horse now too?

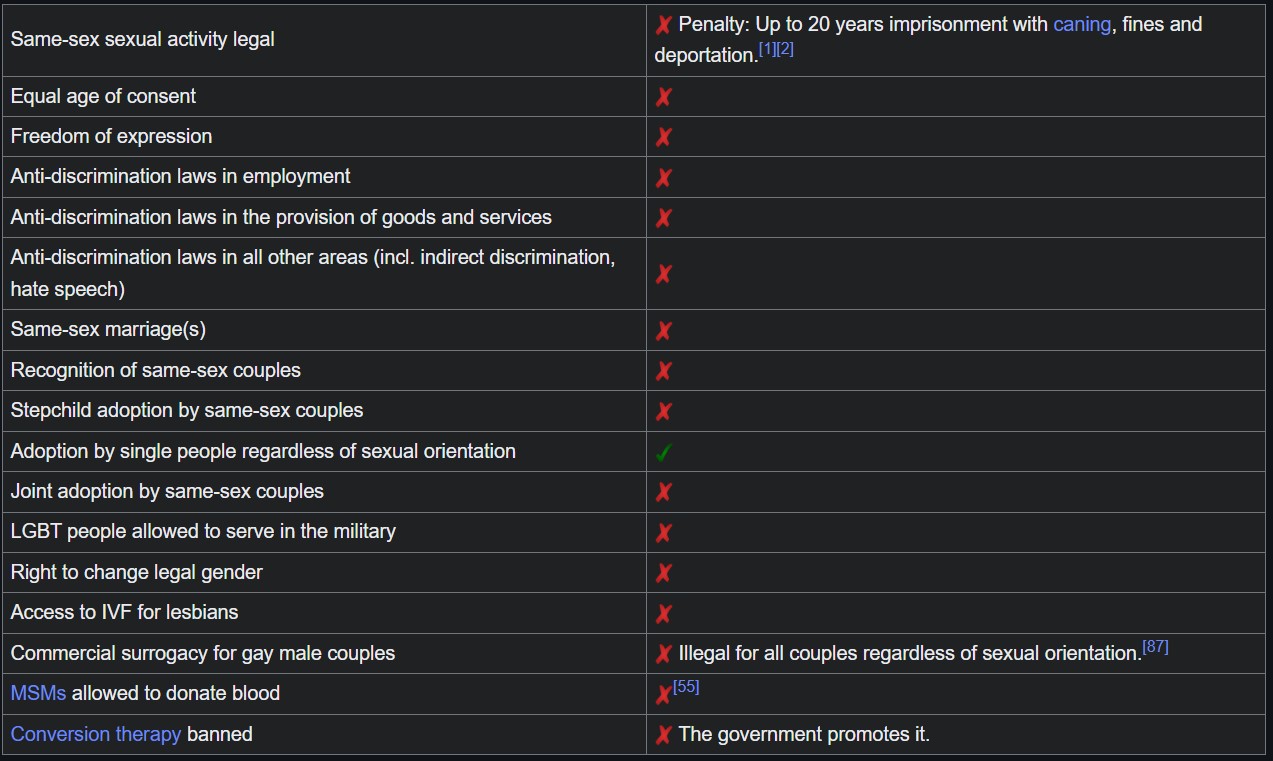

This is clearly not the case in Malaysia. — Tarskian

You're an ignorant werido. I have provided several local reports from legal experts to the contrary. You literally refuse to read them. You're a joke, my friend.

What's more, your meandering word salads won't make any difference whatsoever to the facts on the ground. — Tarskian

That you cannot understand plain English is sufficiently clear. You did not need to be so mean to yourself.

My position on the matter is otherwise perfectly clear. The government should not enforce matters deemed of moral self-discipline unless public order is at stake. — Tarskian

You're now doing the non sequitur. A quaint dance. Once again, no one will be taking you seriously on the back of this. Was that the goal? -

The Liar Paradox - Is it even a valid statement?I agree that if the sentence "this sentence contains fifty words" is inferred to mean that this sentence, ie the sentence "this sentence contains fifty words", contains fifty words, then this is not paradoxical and is false.

However, we are not discussing what the sentence "this sentence contains fifty words" is inferred to mean, we are discussing what it literally means.

And because not grounded in the world, if "this sentence" is referring to "this sentence contains fifty words", it has no truth-value and is meaningless. — RussellA

Why did it take 9 pages. -

Is the real world fair and just?

Agree.creates a caricature "natalist" — apokrisis

caricatured anti-natalism — apokrisis

I think you're wrong, so I can't agree here. Your objections are linguistic in nature and do not affect his actual reasoning (though, I think he's not clear on his own tbh).

Not sure that any society was ever blindly natalist, or even anti-natalist, in the way schop requires. — apokrisis

They have, but under weird guises like 'economy' when in reality, they wanted a bigger army or whatever. It's never been a bare goal though, I'd cop to that.

unlike antinatalism. — 180 Proof

"troll someone else". Caricature of a thinker. -

Avoiding costly personal legal issues in the WestThat outcome is called an "attractor" — Tarskian

So you're now confusing sociology, ideology, philosophy and mathematics. Gotcha.

When every syllogistic chain of arguments leads to the same conclusion, then this conclusion is simply inevitable. — Tarskian

You've not presented a single one to base this on. And, doubtless, your Ps will be entirely false, so what's your point? Syllogisms don't come from Mathematical concepts.

Therefore, I am absolutely not surprised that the South Korean feminist 4B movement comes to this conclusion. — Tarskian

You might be surprised to learn that it is hatred of men, destablising social structures, and avoiding populating the country are their reasons. These are terminal reasons (not to mention they are empirically utterly bereft of evidence for either their reasons, or their purported solution). These are reasons for ending the species, not for changing any kind of dynamic. If their ideology was taken up en masse, we are then in a situation where there are no babies. So, you're an anti-natalists? Very unislamic of you.

So, while you may not be surprised, it violates all the points you're making. If you're not surprised, I'd hazard a guess that once again your ideology is clouding your (obviously functional) reasoning and assessment mechanisms.

The West is terminally doomed. — Tarskian

"the West" is a delusion you are glomming on to to, again, support an unsupportable point.

If you hate the West, live elsewhere are shut the fuck up. -

A quote from TarskianThese gay bars, a multitude of them -- being openly advertised -- seem to be perfectly legal in Malaysia. How is that compatible with your gay-persecution hypothesis? — Tarskian

You may want to re-read all the replies to this erroneous posting, and your ridiculous conclusions.

I also note that you are now relying on 'legality' instead of 'enforcement'. This is because if you read the reports, you'd realise prosecution is rife. You are cherry-picking, and changing your position based on what it supports in your retorts. This is extremely bad thinking, writing and argumentation. First-year critical thinking courses would tie you in knots.

You haven't answered to what seems to be a glaring contradiction in your position on the matter. — Tarskian

You haven't presented one, so I'm not answering to one. This is a mistake on your part, not mine.

Deal with the legal reports, or don't.

there is no need to read your sources of propaganda — Tarskian

Right, so you're a religious zealot who refuses to engage with criticism, 'fact's or evidence. Gotcha brother. Could have said this at the start and saved me the time. I was 100% right - you are under the impression that high-level discourse is the same as low-level discourse, but it isn't. You are floundering here my friend. -

A quote from TarskianHow is that compatible with the following? — Tarskian

What you've posted is a popular article literally advertising specific bars in the area. It has nothing, whatsoever to do with the discussion. Either critique thos several legal reports but local legal experts, or move on. Posting a travel article which is sponsored is not credible. I think it's possible you're under the impression that the level of discussion on these things remains in the same place it does when one speaks from a theocratic position (i.e restrained by belief). This would apply to your beliefs that aren't directly related to your theology too. In this case, you simply 'believe' that things are OK for LGBT people in these places, perhaps because you need to, to reconcile your religious position, with the world around you and your apparently inherent moral code (i.e don't arbitrary criminalise same-sex relationships - yet Islam does, routinely, almost anywhere it gets the chance).

Is it just about any perceived Malaysian distaste for LGBTQ propaganda? — Tarskian

You haven't read the reports, so stop trying to have a conversation about htem. Read them and critique them, if you wish. Otherwise, please stop trying to talk about things you are plainly ignorant of from every conceivable angle.

I also note that you've just swallowed, without reflection, that the term "propaganda" is being used correctly. No. It is not. It is being used to label anything which is visible not heteronormative which is an strictly religious impulse in human history.

It would be better if you asked questions, clarified, and accepted sources and facts that go against your initial position. This should have been an opportunity to learn. -

Donald HoffmanIn Melbourne? I had a short foray in the area (intellectual area) and Melbourne was a hot bed at the time (circa 2010-2015). I still quite like the Thesophical Society Bookstore

-

Is the real world fair and just?They want to see someone else live out X and they make it happen. They force the hand. — schopenhauer1

Not true. Natalism is a population ethic concern and has to do with population growth. We no longer need people to 'have children' to grow the population. This 'guilt' can be lumped on a singular social functionary: The doctor.

I already said you can use what term you’d like. — schopenhauer1

Ok. But you're talking about an established population ethics concept. It would be more reasonable for me to say "pick a different term". THe one you've chosen is taken. -

A quote from TarskianI was recently recommended a podcast hosted by Glenn Loury and John McWhorter. — Leontiskos

Talking Heads right? You might like McWhorter's book. A pretty good antidote the Kendi's, Crenshaw's and DiAngelo's of the world. -

Is the real world fair and just?What does that mean? You were birthed. Does that force you to be a natalist? — apokrisis

You're reading backwards. Any parent that forces a child into life is 'Natalist' on that account there, but Schop is wrong about what Natalism is. He's wrong in his recent reply too, because that particular attitude is not capturing Natalism. -

Is the real world fair and just?Unfortunately, it's worse.

Natalism is a population ethic concept, whereas AN doesn't apply to that set of concerns/issues. Using 'Natalism' as an ethical argument toward any small group, or individual is completely inapt and inhumane (largely). -

The essence of religionYou haven't. There would be evidence in your thoughts and there is none. I really did read all of your long post and found nothing, absolutely nothing of a working intellect. A lot of insults but nothing even remotely about anything these philosophers had to say. — Constance

You are now:

1. Mind reading;

2. Insulting;

3. Refusing to engage;

4. Doubling-down on your incredibly intense failure to be a functional interlocutor.

You are now simply lying to get past the points brought up to you. You haven't engaged a single work, and have (in three consecutive posts) fallen back on pure ad hominem. You are either incredibly dishonest, or incapable of understanding what you pretend to. Either way, go well. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyFair enough!

Sorry to bother you. — Relativist

Not at all! I was far more concerned that my reply would come off bothering to you :P -

What should the EU do when Trump wins the next election?I would say you are explicitly incorrect, or are misusing hte term Fascism which is quite specific, and not just an indicator of violent governmental enforcement.

The U.S isn't even sniffing the arse of fascism currently. -

PerceptionSince "pain" in its scientific representation, is understood to consist of both of these aspects — Metaphysician Undercover

Can you perhaps lay out which two aspects you're referring to, in terms of the scientific understanding? I cannot see any room for the weird "pain in the toe" aspect in any scientific reading I've seen (I don't think!).

Do you agree that it is wrong to say that pain is simply a specific type of touch sensation? — Metaphysician Undercover

Not really, but I think pain from sensory input and pain with no sensory input are the same thing from different sources. The experience is the same. Seeing a shadow in the exact same shape as an actual image (which you can also 'see') might be analogy here. Maybe a slightly better one would be apprehending something's shape due to touch, rather than sight.

In any case I take it that you're trying to get out of me an admission of difference between pain the "Sensory input" and pain the "mental experience". I could probably be pushed. Onward...

"unpleasantness" inheres within the definition of "pain" — Metaphysician Undercover

This does not seem true to me. I think I have covered this earlier. I'm unsure I will go back over it, but a pretty darn clear example is BDSM behaviours or combat sport. For some, "pain" is literally an academic label for something they don't shy away from whereas for most, that is the case.

In the case of pain, unpleasantness is a defining feature, so one cannot feel pain without the unpleasantness, and so this emotional aspect is an "objective" aspect of pain, it is a necessary condition. — Metaphysician Undercover

I just think this is obviously wrong for reasons above, and elsewhere. I am less inclined to be pushed now :P

However, in the case of "pain", unpleasantness is the defining feature of that concept — Metaphysician Undercover

It is not (on my account/view).

We can though, separate the sensory aspect and talk about "pain" as an emotionally based concept — Metaphysician Undercover

It is (on my account/view) a different concept. Emotional pain, it seems to me, is actually a different but related mental experience. Perhaps, a bad one and hte unpleasantness in this concept seems to inhere, but I think you are wrong to conflate them and transitively apply this to "physical" pain. There are blurred lines - being emotionally struck can cause nausea for instance, but is that pain? I should think not. Discomfort.And, the fact that "pain" as an emotional concept, is a true representation of the reality of pain, is evident from experiences such as phantom pain, and some forms of chronic pain. — Metaphysician Undercover

This, for me, seems to indicate exactly the opposite and represents an aberration in a physical signalling system. THe expereince remains the same. -

Personal Identity and the AbyssHow does the reference to the DOJ relate to this discussion? — Paine

Athena was suggesting a bit of TE about how to prosecute crimes when the guy that did it at T1 isn't the same as the guy arrested at T2. I'm saying if Parfit controlled the DOJ, likely we would have to say something like "If he remembers it, cuff him. If not, we can't in good conscience nick him for it".

A weird and unsustainable system indeed, but a bit more toward what the concept of Identity is supposed to capture. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the Bodyjust a separate consideration before we jump onto the idea that we're only correlating — Philosophim

Fair enough mate :)

Do you have the conscious experience of homunculusly controlling a meat puppet through some sort of communication channel? If so, what do the controls (that homunculus-you uses to control meat puppet-you) looks like? — wonderer1

1. Yes;

2. Choices.

This answers nought. Sometimes those choices appear Red to me. This also doesn't answer anything ;)

This seems to suggest that it's OK to believe any theory that isn't provably false. — Relativist

No. "believe" is doing a huge amount of speculative assumption here. I did not intend, nor did I (best I can tell) intimate that i even considered this aspect of the issue as relevant. Belief is not relevant here.

What does it mean to "hold" a theory, but not have it take precedence? — Relativist

Entertain it. Don't write it off (this also, best I can tell, a pretty clear inference from my post - I said it outright at the end). Let it explain what it can for those who want to play with it until it doesn't. Not your circus.

a theory can only be rationally held if it is arguably the "best explanation" — Relativist

In areas where we have no good ones(or at least satisfactory)? Bollocks. Entertain all comers.

Even so, that is often too low a bar to compel belief in it — Relativist

Luckily, I made no attempt to even intimate 'belief' in what I was trying to say. Apologies if this post comes off combative - I feel words were put in my mouth. -

Mental Break DownCouple of times, yes. Less often than the common cold over the same three year period.

-

PerceptionI'm not. I'm saying that our everyday, ordinary conception of colours is that of sui generis, simple, qualitative, sensuous, intrinsic, irreducible properties, not micro-structural properties or reflectances, and that these sui generis properties are not mind-independent properties of tomatoes, as the naive colour realist believes, but mental percepts caused by neural activity in the brain, much like smells and tastes and pain. — Michael

I genuinely think this thread has made it clear that the discomfort with this (apparent) reality is all that lies behind htis debate. -

Mental Break DownSometimes, after all the rules and regulations, it as if Covid is ignored almost. — Jack Cummins

It's treated the same as any relatively scarce illness.

so many issues which were brought on by the pandemic/lockdown — Jack Cummins

For sure. Which is a shame, in light the first bit. -

Personal Identity and the AbyssIt's not just a rule; its our modus operandi. — Vera Mont

I'm not sure they amount to anything different. It could be otherwise, if Parfit controlled the DOJ. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the Bodyit's unparsimonious — wonderer1

I think this is a little bit of a red herring when it comes to theorizing in teh way we do here (or, philosophy in general). I think if the theory has no knock-downs, we can hold unparsimonious theories. They just shouldn't take precedence. But, the "brain-as-receiver" theory is as old as time and has some explanatory power so I like that it's not being written off.

While I hear this argument as strong, it is actually not all that clear and decisive imo. Your analogy between radiowaves and consciousness(waves?) doesn't hold very well at all. It works on the surface, but we know so little about consciousness that to assume it would behave the same way in those contextual scenarios, as radiowaves, is certainly beginning to look like bad reasoning. That said, as above, it's still one of the further-down-the-list ones. All we do know about the brain can still obtain if the 'receiver' type of theory is in some way true (i.e in some way, consciousness is received by the brain..). It's also quite fun, so I really appreciate you making a thorough response in good faith there. Unsure why Sam got upset tbh. -

Antinatalism ArgumentsI think, for me, it's a bit simpler: Not needing ethics would be a goal in this context. No human seems to be the only possible way for that to obtain. Therefore, antinatalism leads to the ultimate ethical goal of never needing ethics.

-

PerceptionThere are many internal pains, sore muscles, stiffness, headaches, stomach aches, and pains of other organs. I don't think it's proper to call such pains a sensation of touch. — Metaphysician Undercover

These are all examples of physical touch, though? These are all situations where some physical force exerted on the pain receptors has triggered a signalling cascade to your brain. Maybe there's more to be said, but I don't see a different other than in sort of spatial locale. I can hurt my tongue by running it along the edges of my front teeth, as an example. The tongue is a muscle.

I also do not think this proposed distinction between pain and discomfort is useful. What one person calls discomfort, another would call pain. What is subjective is the proposed distinction. — Metaphysician Undercover

I think this is shying away from the real meat here. It's not a distinction. Pains are generally uncomfortable, but not always. Discomfort is largely not painful (without the former being the case, if you see what i mean). They come apart and are distinct, but I'm not trying to put them in a relation to one another.

Do you not have internal pains? These are not the result of any of the five known senses. You are not touching your stomach when you feel a stomach ache — Metaphysician Undercover

Addressed above, A stomach ache, generally, is the physical (sensory) event causing pain internally (though, you're actually describing discomfort here so I'm not sure your objection works anyway - internal "pain" is generally hte result of an actual physical aberration - say, a torn stomach lining. All of these feelings arise from sensory data, internal or external. I think you are insinuating that internal pain is not 'caused'? What could it be caused by if not sensory data (just, from within, not without)).

You start with the faulty assumption that pain is produced from the sense of touch, and you proceed from that false premise. — Metaphysician Undercover

You say it's false - i think you haven't shown that at all. I'm unsure you've even shaken my position with what you've said...

Pain is not produced from the sense of touch, as internal pains demonstrate. — Metaphysician Undercover

Dealt with, and I disagree with your account of pain. It seems plainly wrong, empirically speaking.

If you knew some of the science about how pain is supposed to be an interaction between the brain and the inflicted part of the body, through the medium of the nervous system, you would recognize that your proposition is very likely false. — Metaphysician Undercover

I do. And that is actually exactly why it appears to be true to me. What are you specifically referencing here? I ask, because all we know about pain seems to violate your position in many ways.

Some excerpts that are apt here:

"Nociception refers to ... processing of noxious stimuli, such as tissue injury and temperature extremes, which activate nociceptors and their pathways.

...

"The receptors responsible for relaying nociceptive information are termed nociceptors; they can be found on the skin, joints, viscera, and muscles.

...

"Pain perception begins with free nerve endings ... The multitude of different receptors conveys information that converges onto neuronal cell bodies in the dorsal root ganglion (stimulus from the body) and the trigeminal ganglia (stimulus from the face). There are 2 major nociceptive nerve fibers: A-delta fibers and C-fibers. A-delta fibers are lightly myelinated and have small receptive fields, which allow them to alert the body to the presence of pain. Due to the higher degree of myelination compared to C-fibers, these fibers are responsible for the initial perception of pain. Conversely, C-fibers are unmyelinated and have large receptive fields, which allow them to relay pain intensity.

...

"The body is also capable of suppressing pain signals from these ascending pathways. Opioid receptors are found at various sites ... The descending pain suppression pathway is a circuit composed of (the part missing here doesn't matter, i'm just connecting the following to the whole piece) .. It suppresses information carried via C-fibers, not A-delta fibers, by inhibiting local GABAergic interneurons."

It then speaks about how in some complex pain disorders, the pathway is aberrated and signals cross, weaken, intensify etc... due to a couple of conditions, but describes them in the above terms.

This is how Tylenol is thought to work, by affecting the part of the brain which sends the pain signal. — Metaphysician Undercover

This does not seem to be the case, at all. Unfortunately, it doesn't even seem reasonable to suggest that the brain sends a "pain" signal to the injured area. How would that even work? Where does it land? What does it do? Cause the area to simply relay more pain signals to the brain? This is getting a little silly, tbh.

It seemed to me, though I do not have the resource on hand, that the way most pain medications work (Tylenol included) is inhibiting the brain's pain receptors so as to uptake less signal from the affected area (or, none, in some cases). I did find this:

"...by directly inhibiting the excitatory synaptic transmission via TRPV1 receptors expressed on terminals of C-fibers in the spinal dorsal horn. Contrary to previous studies on the brain, we failed to find the analgesic effect of acetaminophen/AM404 on the CB1 receptor on spinal dorsal horn neurons."

This directly suggests that all that is happening is that the signals from the affected area are arrested along the ascending pain pathway. -

The essence of religionMight I remind you of your juvenile intrusion into this thread?: — Constance

I have provided several hundred words of analysis of your writing. You have addressed absolutely none of it - you've preened, ignored, and now devolved into pure ad hominem. That has nothing at all to do with me and my comportment. You are behaving like an angry 14 year old who has had their playstation taken away.

Did you not mention later that I was committing a non sequitur — Constance

Because you did. You did it constantly, and it gets called what it is. This isn't insulting in any way. It is a comment on your (terrible) writing style. If you cannot handle having your incoherence called out, perhaps don't write confused, incoherent posts on a philosophy forum inviting comment?

There is no argument here, no mention of anything remotely related to the OP, not even a single thoughtful construction. — Constance

Is it possible you are just not being honest? Not only possible - clearly true.

You got no more than your deserve, you inelegant ass. — Constance

You are now just being a dick. If this is how you respond to analyses of your bad writing, well... All i can do is laugh. You had the chance to engage with some ideas (thoroughly connected to your own writing, in direct response to it). You, instead, shied away from doing any thinking and just started insulting me. I've made some off hand comments about Continental philosophy and your writing being bad. If you identify so strongly with either thing you take them as personal insults, triggering your emotional outbursts, please get some help. -

A quote from TarskianYou really don't know Indonesia, do you? — Tarskian

I do, actually. It strikes me as quite odd that you'd assume a lack of knowledge when I;'ve provided the sources... Your link has absolutely nothing to do with anything under discussion, and I note you have not bothered to look at the sources provided.

He is almost surely exaggerating about "gay persecution": — Tarskian

https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/malaysia-questions-18-people-arrested-lgbt-halloween-party-2022-10-31/

https://www.asiasentinel.com/p/growing-persecution-lgbtq-malaysia

https://www.article19.org/resources/malaysia-stop-the-criminalisation-of-lgbtqi-individuals/

https://www.petertatchellfoundation.org/matty-healey-not-a-white-saviour-for-condemning-malaysian-homophobia/ (the article is somewhat irrelevant (as is Tatchell) but hte basis for it is what's interesting)

https://www.voanews.com/a/malaysian-authorities-raid-lgbt-halloween-party/6811548.html

https://www.humanrightspulse.com/mastercontentblog/the-persecution-of-transgender-people-in-malaysia

https://www.reuters.com/article/world/malaysia-cannot-accept-same-sex-marriage-says-mahathir-idUSKCN1M10UW/

Yeah, totally exaggerating.

Concerning Indonesia, you don't know what you are talking about, do you? You simply have no clue whatsoever. — Tarskian

I, in fact, do. I take your continuous denial of the facts on board.

I have no clue about how things are in Malaysia for homosexual people. — Tarskian

No, you don't.

I personally consider casual sex to be rather lawless behavior. — Tarskian

This sentence is incoherent.

So back to the start, I guess:

I have, though, provided you multiple academic legal opinions to the contrary - at least oen from within Indonesia. Malaysia, I am less ofay with.

— AmadeusD

You really don't know Indonesia, do you? — Tarskian

Please, feel free to critique several reports from legal experts in the region. -

Donald HoffmanI can't see the * comment, but this is plainly a misuse of 'literally'. If taken 'literally' it is, after investigation, entirely false. If taken as a description of appearances (i.e not to be taken literally) then it goes through. — AmadeusD

The stars and the Sun do orbit the Earth in the earthbound frame — SophistiCat

They do not. This is what 'taking it literally" precludes. This is not actually happening, no matter how it may appear so. Literally, the Earth turns and gives an appearance (which is not a true appearance) of other bodies orbiting the Earth (though, I've never understood this one. It seems clear to me the Earth turns on bare observation.. no matter). So, if it wasn't your intention, that's fine, but including the "literally" aspect means that the claim is false.

just not quite the way — SophistiCat

Not - at all - the way they ancients thought of it, which was a mistake. They described what appeared to be happening. It was not, and is not, 'literally' happening no matter the 'frame'. The frame is irrelevant to a literal reading. -

A quote from TarskianIn my Indonesian and Malaysian experience, it simply is. — Tarskian

I have, though, provided you multiple academic legal opinions to the contrary - at least oen from within Indonesia. Malaysia, I am less ofay with.

Again, what's on the books is irrelevant. — Tarskian

Then you are talking into the ether, from the ether. Which is fine, but it makes your responses fairly empty. You're defining-out some of the most important pieces of data to support a view point - not always horrid, but in this case, it is quite unfortunate as it amounts to moving the goalposts. If your entire view rests on "I don't think they would do that...." in response to bad policies, we ahve not much to discuss as that's just an opinion.

The above is simply unenforceable. — Tarskian

Plainly untrue. This is entirely enforceable, i'm unsure why you would suggest otherwise. If a report is filed, and the police process the report, it can be prosecuted. End of discussion. Whether someone is convicted is neither here nor there, but given the general biases against women in the penal system there, it is not at all out of the realm of reasonable assumption that at least one woman will be charged and convicted. THe possibilitiy is enough to uphold hte objection I'm making.

I am a foreigner in these countries. — Tarskian

This is not relevant to our discussion. If you're centering yourself, I don't know why you're talking to others about it.

You seem to be confused as to the role of the Islamic clergy — Tarskian

No. It appears that you pick and choose theory and practical results when it suits. Muslim Clergy are the ruling class by proxy in almost all Muslim-majority nations. Sharia is hte law of hte land? Ok, then Clergy are the judges. That's how that works. Pretending it's not because the titles don't reflect it is like saying the USA is not, in any way, oligarchical. It's a farce.

is substantially different from the army, the police, or the security forces in general. — Tarskian

They are all required in service of the faith and Islamic Law regulates how this is done (in all those cases). They are, all of them, theocratic outsources. If this were not the case, you could have a Catholic leader of the Iranian defense force (whatever it's named Properly).

AmadeusD

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum