-

Direct realism about perceptionYou’re treating phenomenal character as that which is assessed for correctness in the act of perception — Esse Quam Videri

No, I'm saying that it's the thing directly seen. From this we then make judgements about the world that can be correct or not (if indeed we do; much of the time I experience things without making any kind of judgement). -

Direct realism about perceptionIn veridical perception, that judgment is answerable to objects in the environment and can be corrected by further interaction with them. In hallucination, the same kind of judgment is made, but it fails—there is no object that satisfies it. No inner surrogate is thereby promoted to the status of what is assessed; rather, the judgment is simply false. — Esse Quam Videri

As I said a few days ago, these judgements do not occur apropos of nothing. Excluding the obvious cases of mathematics and logic, it is the phenomenal character of experience that prompts and directs our judgements. I say "there is a white and gold dress" when the appropriate visual phenomena occurs. If the experience is veridical (to the extent that colour experiences can be veridical), the judgement is true. If the experience is an hallucination, the judgement is false. In either case it is the visual phenomena (including its character) that acts as "immediate object of assessment". -

Direct realism about perceptionIf the bionic eye is integrated into perception such that judgments are still answerable to objects through ongoing interaction and correction — as with natural, transplanted, or lab-grown eyes — then there is no epistemic intermediary, and perception is direct in the sense I’m using.

The visor and nerve-stimulation cases differ because they interpose a surrogate whose adequacy depends on a generating process that stands in for the world, rather than being part of the perceptual relation itself. — Esse Quam Videri

What's the difference between a bionic eye that is "integrated into perception such that judgments are still answerable to objects through ongoing interaction and correction" and a bionic eye that is a "surrogate whose adequacy depends on a generating process that stands in for the world"?

It just seems like there's a lot of special pleading here.

Whether an organic eye or a bionic eye, there is something that takes electromagnetic radiation as input, carries out transduction according to some deterministic process, and then stimulates the optic nerve.

Without begging the question, what determines whether or not the physical intermediary between the electromagnetic radiation and the optic nerve is an epistemic intermediary? I don't think there is such a thing, e.g. proteins are not privileged over silicon.

So either perception is direct both with the bionic eye and the organic eye or perception is indirect both with the bionic eye and the organic eye.

If you say that perception is direct both with the bionic eye and the organic eye then we return to the Common Kind Claim: whatever is the "immediate object of assessment" when the eye (whether bionic or organic) is "malfunctioning" must also be the "immediate object of assessment" when the eye isn't "malfunctioning" — and in the former case that thing cannot be an object in the external world because the thing we're seeing doesn't exist in the external world; therefore in the latter case that thing cannot be an object in the external world either. -

Direct realism about perceptionI would say that there is no relevant difference of the kind you are asking for — because the distinction I’m drawing is not about the material or biological status of the causal chain at all — but about the epistemic role it plays.

In ordinary perception — regardless of whether the eye is natural, transplanted, or artificially grown — one’s judgments are answerable to objects in a shared environment through ongoing interaction and correction... — Esse Quam Videri

So why is this not also the case for the bionic eye? It simply replaces rod and cone cells with silicon chips. -

Direct realism about perceptionIn both cases, what the subject’s judgments are immediately answerable to is a generated input whose correctness depends on how it was produced, rather than to the objects themselves. That is the sense in which the perception is indirect. — Esse Quam Videri

Then what is the relevant difference between these:

1. An artificial bionic eye

2. An artificial organic eye (identical to a natural eye, but grown in a lab)

3. A transplanted natural eye

4. The natural eye one was born with

All work by taking electromagnetic radiation as input and then stimulating the optical nerve according to some deterministic process. -

Direct realism about perceptionThe visor case is instructive precisely because it introduces an epistemic intermediary whose outputs are the immediate objects of assessment. — Esse Quam Videri

So let's amend the scenario slightly. Instead of there being a screen on the inside that outputs light towards the eyes it has wires connected directly to the optical nerves and stimulates them in the "appropriate" way, i.e. the visor is a "bionic eye".

Would you still accept that these people only have indirect perception of the world beyond the visor, or does it now qualify as direct perception? What are the immediate objects of assessment? If the Common Kind Claim is to be believed then whatever are the immediate objects of assessment when the bionic eye is malfunctioning (e.g. causing their wearers to see things that aren't there) are also the immediate objects of assessment when it's working as intended. -

Direct realism about perceptionFor the direct realist, the chain is the mechanism by which the world shows itself... — Banno

The problem with this is that it makes the word "direct" in the phrase "direct perception" meaningless. This is highlighted by your assertion that these people with their visors still directly perceive their shared environment. You appear to be arguing that the visor and its screen is "the mechanism by which the world shows itself".

Whereas I think this visor and its screen functions exactly like a Cartesian theatre, and a Cartesian theatre is exactly the sort of thing that would qualify as indirect perception (but isn't required for indirect perception, as I've argued before). So you've defined "direct realism" in such a way that even the strawman misrepresentation of indirect realism would count as direct realism.

And while they are seeing the image on the screen and they are seeing the ship and they are talking about the ship, each of these has a slightly differing sense, each is involved in a different activity. — Banno

According to the indirect realist, the same is true ("each of these has a slightly differing sense") even without the visor.

1. There is perceiving mental phenomena (e.g. colours in the sui generis qualitative sense of the term) — which is not to be understood in the sense of a Cartesian theatre but in the sense of the seeing and hearing that (also) happens when we dream and hallucinate.

2. There is perceiving distal objects (e.g. a dress).

3. There is talking about the mental phenomena (e.g. "I see white and gold").

4. There is talking about the distal object (e.g. "there is a dress").

The substantive philosophical claims are that a) (2) only happens in virtue of (1) and that b) (2) does not satisfy the philosophical notion of directness, e.g. as explained here — with the example of the visor showing that (2) doesn't need to be direct for (4) to happen. -

Direct realism about perception

So here's the thing; anyone can mean anything by the words "direct" and "indirect". It is possible that direct and indirect realists each mean different things by the words such that perception is direct in the sense that direct realists mean by the word "direct" and that perception is not direct in the sense that indirect realists mean by the word "direct", and so that the dispute is nothing more than two groups of people talking past each other.

But I don't think that this is the case, at least traditionally. I think that both groups mean the same thing by the words. I think that naive colour primitivism is exactly what was meant by direct realism, with Locke's distinction between primary and secondary qualities being exactly what was meant by indirect realism. This appears consistent with the definition of direct realism as explained here, where one of the stipulations is that "the phenomenal character of experience is determined, at least partly, by the direct presentation of ordinary objects".

You used the phrase "perception relates us directly to mind-independent objects", but what exactly does it mean for perception to "relate us directly" to mind-independent objects? Consider this example of a society of people who wear visors with sensors on the outside and a screen on the inside displaying a computer-generated representation of their environment. Does their perception "relate them directly" to their environment? They certainly can talk about and make judgements about their environment, but must there be more to it? Will you say that these people "directly perceive" their environment, as Banno says? You're more than welcome to define "direct perception" in such a way that such a proposition is true, but I think it very obvious that this is not what is traditionally meant, either by indirect realists or their direct (naive) realist opponents, both of whom will agree that these people do not directly perceive their environment (even if they disagree over whether or not these people directly perceive the screen). Once again, I think it's semantic direct realists introducing a philosophy distinct from phenomenological direct realism, and which is consistent with (phenomenological) indirect realism (as that article argues). -

Direct realism about perception

I was referring to the example of the people with visors on their heads, with sensors on the outside and a screen on the inside displaying a computer-generated representation of their environment.

Even if direct realists want to argue that these people directly see the screen on the inside of the visor they must accept that they do not directly see the environment outside the visor. Yet these people can still talk about the environment outside the visor, not only about their screens.

So Banno's argument that if indirect realism is true then we can only talk about our private experiences is evidently invalid. We don't need direct perception of something to talk about it. -

Direct realism about perceptionThe mere possibility of global deception does not by itself show that perception is indirect, nor that the world is not as it appears. — Esse Quam Videri

This has it backwards. The indirect realist claim is that because a) perception is indirect b) the world might not be as it appears and so c) there are legitimate grounds for scepticism, and the direct realist claim is that because d) perception is direct e) the world is as it appears and so f) there are no legitimate grounds for scepticism.

I'm not using (c) to justify either (a) or (b). I am:

1. Citing sources that show that in the context of this discussion the meaning of the phrase "direct perception" is such that if (d) is true then (e) is true

2. Arguing that our scientific understanding of the world shows that (e) is false (e.g. naive colour primitivism is false)

3. Concluding that (d) is false and that (a) is true

I can understand you arguing that (c) does not follow from either (a) or (b) and that (f) does not follow from either (d) or (e), but I think this is secondary to the primary issues of (a), (b), (d), and (e). -

Direct realism about perceptionOne simply judges that there is a ship, and that judgment is assessed over time by its coherence with other judgments, its responsiveness to further experience, and its success or failure in inquiry. — Esse Quam Videri

All of which can happen if we are hallucinating ships. In the extreme sceptical scenario we are brains-in-a-vat. This is not to say that indirect realists argue that this is probable, only that this is possible. You could argue that such scenarios are fantastical and unfalsifiable, and so unworthy of consideration, but I don't see this as refuting the core claims that perception of the external world is indirect and that it is not as it appears. -

Direct realism about perceptionBy perceptual belief I mean something more ordinary and less theory-laden: they are beliefs about objects and states-of-affairs that are formed in ordinary perceptual contexts (e.g. “there is a ship”, “the screen is emitting orange light”, “the umbrella is wet”). — Esse Quam Videri

Okay, so this is where the Common Kind Claim comes in. If we accept that (2) is false (that perception is not direct) then the phenomenal character of an hallucination can be indistinguishable from the phenomenal character of a so-called "veridical" experience.

If my "background knowledge" is the same in both the "veridical" and the hallucinatory case (which surely it must be, unless hallucinations necessarily affect memory), and if the phenomenal character of an hallucination can be indistinguishable from the phenomenal character of a "veridical" experience, then how can I justify my belief that I am not hallucinating? Other than the (questionable?) assertion that I ought assume that all experience is "veridical" unless I have a good reason to believe otherwise, it would seem that I cannot justify such a belief.

Although I personally find these sceptical conclusions to be secondary to the primary issues of (1) and (2), and especially to (2). If the answer to (2) is "no" then indirect realism is correct, even if its further conclusions (and other assumptions) are unwarranted. -

Direct realism about perceptionI think the issue is that your formulation of (1) already presupposes a particular conception of justification — namely, that perceptual beliefs are justified if and only if the world is “as it appears”. — Esse Quam Videri

Perhaps, but then by "perceptual belief" I mean "a belief that the world is as it appears". What do you mean by the term?

So to be very explicit, I'll rephrase (1):

1. Is direct perception required for us to be justified in believing that the world is as it appears?

2. Is perception direct?

If you want to argue that our perceptual beliefs (whatever they are) are justified even if the world isn't as it appears then I'm not sure it's relevant to the direct and indirect realist's concerns. This really depends on what counts as a perceptual belief. -

Direct realism about perception

Then we have two separate questions:

1. Is direct perception required for our perceptual beliefs about the world to be justified?

2. Is perception direct?

Direct and indirect realists likely agree that the answer to (1) is "yes", with direct realists arguing that the answer to (2) is "yes", and so concluding that our perceptual beliefs about the world are justified, and indirect realists arguing that the answer to (2) is "no", and so concluding that our perceptual beliefs about the world are not justified.

You appear to agree with the indirect realist that the answer to (2) is "no" but disagree with both the direct and indirect realist that the answer to (1) is "yes"?

I think you might be misinterpreting (1). It's not supposed to be interpreted as "does the phenomenal character of experience justify our beliefs about the world?" but as "are we justified in believing that the world is as it appears, i.e. that the phenomenal character of experience is (or resembles) the mind-independent nature the world?" (with naive colour primitivism being the exemplar of such a notion). -

Direct realism about perception

Then I really don't understand what you are trying to argue, or how it relates to the dispute between direct and indirect realism.

Again, the direct realists argued that a) the phenomenal character of experience is the direct presentation of mind-independent objects and their properties, such that b) we can infer (deductively, even) from the phenomenal character of experience that "there are in nature colors, of a distinctive kind that we are all familiar with, i.e., ... simple intrinsic, non-relational, non-reducible, qualitative properties".

Indirect realists argued that (a) is false, and so that because of this (b) is unjustified, and possibly false, i.e. it is possible that the mind-independent nature of the world is radically different to the phenomenal character of experience ("the world isn't as it appears"). -

Direct realism about perceptionphenomenal character is not truth-apt and cannot function as a premise — Esse Quam Videri

Phenomenal character isn't truth apt but the premise "I am experiencing such-and-such phenomenal character" is, and so this latter proposition can function as a premise. It's exactly how John and Jane come to their respective conclusions.

John

P1. Electromagnetic radiation with such-and-such wavelengths usually cause people to experience such-and-such phenomenal characters

P2. I am experiencing such-and-such (e.g. orange) phenomenal character

C1. Therefore, the screen is probably emitting electromagnetic radiation with such-and-such a wavelength (e.g. 600nm).

Jane

P1. Electromagnetic radiation with such-and-such a wavelengths usually cause people to experience such-and-such phenomenal characters

P2. I am experiencing such-and-such (e.g. red) phenomenal character

C1. Therefore, the screen is probably emitting electromagnetic radiation with such-and-such a wavelength (e.g. 700nm).

Without each P2 each C1 would be a non sequitur, and given that P1 is the same for both John and Jane there would be no explanation for why each C1 is different. -

Direct realism about perceptionConsider the example of John and Jane that ↪Michael provided. Jane makes a perceptual judgment (“the screen is orange”) and infers that the wavelength of the light is between 590nm and 620nm. Appealing to an introspective judgment (“I am seeing orange”) in order to justify her perceptual judgment simply won’t convince anyone, including herself. If she really wants to justify her judgment that the screen is orange, she’ll need to appeal to her background knowledge (optics, screens, color-blindness, etc.) and further perceptual judgments about her environment (current lighting, viewing angle, screen filters, etc.). — Esse Quam Videri

I didn't mean to suggest that the phenomenal character of experience is sufficient to infer mind-independent facts about the environment (although the naive colour realist does suggest this, and is wrong). Obviously if neither John nor Jane know anything about electromagnetic radiation then they wouldn't infer anything about the wavelength of light emitted by the screen.

It doesn't follow from this that they don't infer mind-independent facts about their environment from the phenomenal character of experience. Given their background knowledge of electromagnetic radiation, computer screens, etc., it is then the phenomenal character of experience that allows them to choose between "the screen emits ~700nm light", "the screen emits ~600nm light", etc, with John's and Jane's different inferences being explained by them having different phenomenal experiences. -

Direct realism about perceptionIn your visor world, the visors drop out of the discussion when folk talk about ships. They are not seeing the image on the screen, they are seeing ship. — Banno

"Seeing" and "talking about" do not mean the same thing. They are seeing the image on the screen and they are seeing the ship and they are talking about the ship.

It simply doesn't matter what "drops out of [their] discussion". If it helps, consider us to be secret observers, e.g. the mad scientists who engineered these people. Their visors do not "drop out of" our discussion. We ought accept that they do not directly see their shared environment.

That's not a redefinition. — Banno

Yes it is. There is no reasonable account under which these people can be said to directly see the ship (as the term "directly" means in the context of the dispute between direct and indirect realism). A scenario like this is exactly what it means so see something indirectly. -

Direct realism about perceptionAll of this is presented as implicitly rejecting the idea that meanings are fixed by hidden reference-makers (phenomenal or physical), and treating meaning instead as constituted by the public criteria governing a word’s use within a practice. That is, there are in fact all sorts of internal things going on in your mind that may in fact be the cause of your utterances, but we don't fix meaning by those, but we fix it by usage. Your example makes that clear, showing that regardless of the internal causes, even when they are dissimilar across speakers, the language game makes sense upon relieance upon usage without worrying about the internal causes. — Hanover

And yet the example should show that the usage will change if the phenomenal character of experience changes, even though nothing about the strawberry or the light changes, so clearly the phenomenal character of experience also has something to do with the meaning of the word "foo" in their language.

Although, saying that the usage will change is somewhat ambiguous. It changes in the sense that they no longer describe strawberries as being "foo-coloured", but then that would also be true if rather than a secret surgery on their eyes someone secretly dyed strawberries (and every other "foo-coloured" thing). This will change which things are described as being "foo-coloured" but it doesn't follow that the meaning of the word "foo" has changed.

I think an important point to mention when we say "meaning is use" is that it completely disentangles metaphysics from grammar. Grammar answers the question of how we use words. When I say "I see a ship" and you ask what is a "ship," under a meaning is use analysis, the "ship" is defined by how it is used. If you start asking about the atomic structure of the ship and how the photons bounce off the boards to your optic nerve, you are answering a very different question. — Hanover

I agree that metaphysics and grammar are different things; I just disagree with the claim either that the phenomenal character of experience is not real or that it does not have anything to do with language. It's real, and like every other real (and even unreal) thing in the universe, we can talk about it. -

Direct realism about perceptionthe fact that they are "in a very real sense" referring to their beetle in their box doesn't mean we now get to understand what those beetles are. — Hanover

I'm not claiming that we do. I'm only showing that our words can, and do, refer to these beetles.

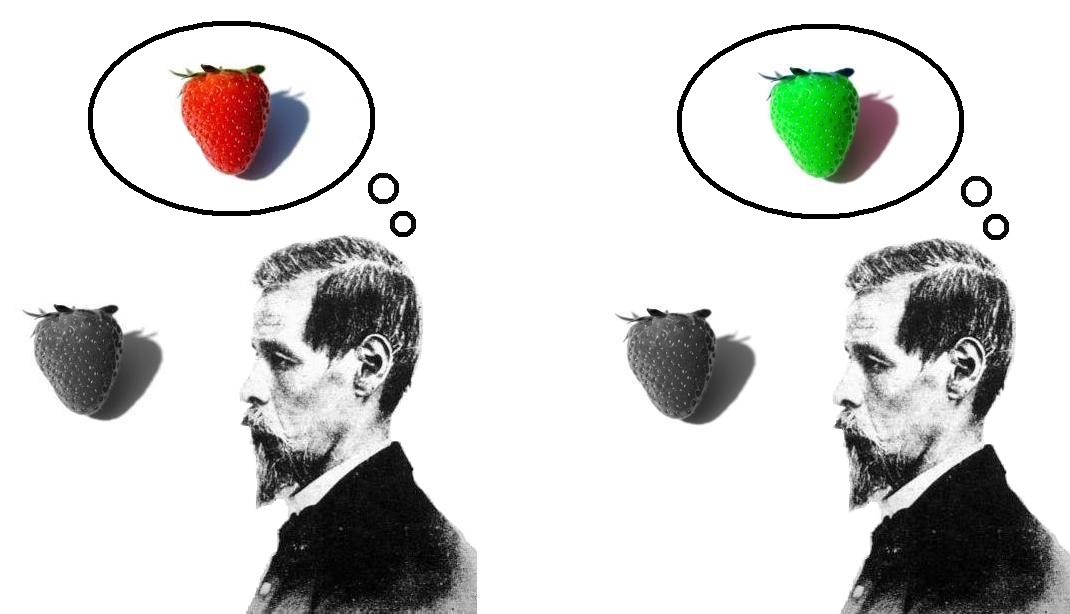

In a situation like the below, both may agree with the proposition "the strawberry is foo-coloured", and may even agree that the word "foo" (sometimes) refers to a disposition to reflect a particular wavelength of light, but I think it unproblematic to accept that the word "foo" also refers to the private phenomenal character of the individual's experience, even if neither can know the other's. If someone were to secretly surgically alter their eyes and/or brains such that the phenomenal character was switched then each would say "the strawberry is no longer foo-coloured" (and then be very confused when they measure the wavelength of light and detect no change).

-

Direct realism about perception

For the sake of argument, let's assume that direct realism is true. I directly hear the sound waves being produced by my telephone. Do I (directly) experience the "causal link" between these sound waves and my mother on the other end of the line? No. Does this matter? No. Does it follow that I don't (indirectly) hear my mother talking? No. Is it possible that I'm being deceived and that it isn't really my mother speaking on the other end of the line? Sure. Am I justified in believing that it's probable? Not really.

The same principle applies to indirect realism; it just draws the line that separates the direct from the indirect at a different place in the world, and as I believe I showed with my example of the society of people with visors, this line can be drawn in such a way that nobody ever directly sees what another directly sees, and yet they can still have a functional language and knowledge of their shared environment. -

Direct realism about perception

As I clarified in my comment, I meant to say that I take no stock in the private language objection to indirect realism. You claimed that if indirect realism is true then we cannot talk about our shared environment, only our private experiences, and so that because we can (must?) talk about our shared environment then indirect realism is wrong. I showed that your premise is false, and so that your argument fails. These people do not directly see their shared environment (given the visors) and yet can still talk about it.

Indeed, it supports direct realism by showing that we routinely and intelligibly “see through” intermediaries without reifying them as perceptual objects. — Banno

You're seriously trying to redefine "direct perception" in such a way that even with these visors and their computer-generated images on a screen they still directly see their shared environment? This is absurd, and is precisely the problem I highlighted at the end of this post. You're taking what is very clearly indirect perception, butchering the meaning of the words "direct" and "indirect" to mean something else, and then taking this as proving the indirect realists of their world wrong. It's dishonest, and equivocation. -

Direct realism about perceptionAnd their language would be public and therfore not disproving the PLA. The PLA is not dependent upon unmediated access to the environment. In fact, Wittgenstein says nothing about whether the world is mediated through the senses or not. He's talking about words and how they can have meaning. — Hanover

I slightly misworded my first sentence. I meant to say that I hold no stock in the argument that the PLA refutes indirect realism.

But on the PLA, let's assume that John's and Jane's screens each output different colours in response to the same wavelengths of light, but in a consistent manner. Do you accept that a) they will both use the word "foo" in their language when asked to describe the colour of grass, that b) there is a very real sense in which when they use the word "foo" they are referring to the colour output by their private screen, and that c) it is intelligible for each to wonder if the other's private screen outputs a different colour when looking at grass? -

Direct realism about perceptionHow is that in any way contrary to the private language argument? These folk are talking about their shared environment, not their unshared screen time... — Banno

I meant to say that I hold no stock in the argument that the PLA refutes indirect realism. You appear to be accepting that these people are talking about their shared environment even though none of them ever directly see it (which even the direct realist must accept given the visors). The only thing these people ever directly see (even assuming direct realism) is their private screen.

So your entire objection falls apart. -

Direct realism about perception

I hold no stock in the private language objection. A society of people born with unremovable visors on their heads with sensors on the outside and a screen on the inside displaying a computer-generated image of the environment could develop a language, talk about the environment, and lives their lives just as well as we can. Let's even throw in the inverted spectrum hypothesis and have different screens output different colours (but consistent for each individual), just for fun. -

Direct realism about perceptionYou are losing me here.

Sure, when we use a telephone we hear someone indirectly. Are you suggesting that undermines direct realism? — Banno

You said this, as if it were objectionable:

"Pretty ad hoc. Now we have both direct and indirect perception happening in the same individual for the same event."

It's not objectionable. It's quite ordinary. We just disagree on which things fall within the category "direct" and which things fall within the category "indirect".

Yep. But he is not only a mental image, or a firing of brain cells. He is public in a way that whatever indirect realists say they see, isn't.

It appears to me that you have moved on to equivocating about what it is that indirect realists suppose it is that is perceived. — Banno

You claimed that it's impossible to talk about things unless we can see them directly, and so I provided an example of something that we can talk about but haven't seen directly. So your objection fails.

We don't directly see Napoleon but can still talk about him. We don't directly see ships but can still talk about them. -

Direct realism about perceptionNow we have both direct and indirect perception happening in the same individual for the same event. — Banno

Yes? That's how indirect perception works. You directly perceive some X and because of that indirectly perceive some Y. Even the direct realist must accept that this is how television and telephones work.

That's exactly right. We can talk about Napoleon because there is more to him than the firing of neutrons. He is not an hallucination. — Banno

The point is that we don't need to directly see him to talk about him, and we don't need to directly see ships to talk about them. -

Direct realism about perceptionIf the thing one sees is only ever "the visual cortex being active in the right kind of way" then we would have no basis for agreeing that there is a ship. — Banno

I didn't say only ever. I explicitly said here that "in the non-hallucinatory case there is both hearing voices-as-mental-phenomena and hearing voices-as-distal-stimulus", with the former satisfying the philosophical notion of directness — as explained here — and the latter not.

If what one really sees is always private — cortex states, sense-data, whatever — then nothing in experience can fix reference to a public object. — Banno

I object to this use of the word "really". It's a weasel word, as you said. The proper phrase in the context of this discussion is "directly see" — again, as explained here.

And we don't need to directly see something to "fix reference" to it. You and I can both talk about Napoleon. -

Direct realism about perceptionOn the view I’m defending, epistemic directness is not a matter of what is phenomenally present to the mind at all.

...

Directness, on my view, concerns what our judgments are about, not what appears in experience. — Esse Quam Videri

But direct (naive) and indirect realism, as traditionally understood, are concerned with what sorts of things are phenomenally present to the mind (and the epistemological implications). That's the nature of their disagreement.

I've addressed this elsewhere, but I think part of the problem here is that there are newer brands of "direct realism" that, in adopting the term "direct realism" to mean something else, have fabricated a dispute with indirect realists that isn't really there. Indirect realists aren't necessarily in conflict with every position that calls itself "direct realism". We need to look past superficial labels to the substance of the claims made.

An article I often refer to in these discussions is Semantic Direct Realism:

The most common form of direct realism is Phenomenological Direct Realism (PDR). PDR is the theory that direct realism consists in unmediated awareness of the external object in the form of unmediated awareness of its relevant properties. I contrast this with Semantic Direct Realism (SDR), the theory that perceptual experience puts you in direct cognitive contact with external objects but does so without the unmediated awareness of the objects’ intrinsic properties invoked by PDR. PDR is what most understand by direct realism. My argument is that, under pressure from the arguments from illusion and hallucination, defenders of intentionalist theories, and even of relational theories, in fact retreat to SDR. I also argue briefly that the sense-datum theory is compatible with SDR and so nothing is gained by adopting either of the more fashionable theories. -

Direct realism about perception

The problem is that you are using your definition of "I see X" (such that it is true only if X is a real object in the environment) to (mis-)interpret their claim "I see mental phenomena" (and is why your accusation that indirect realism entails an homunculus is a strawman).

The indirect realist might argue that "I see X" just describes the visual cortex being active in the right kind of way, regardless of what the eyes are doing or what distal objects exist, and so I see things when I have visual hallucinations and hear things when I have auditory hallucinations (and don't see or hear anything if I have brain damage but otherwise functional eyes and ears). This is an ordinary use of English vocabulary.

And the things I see and hear when I hallucinate have properties that can be described, such as their colour, and is how we distinguish between hallucinating one thing and hallucinating something else. Given that there is no real object in the environment when I hallucinate, the colours I see when I hallucinate are not microstructural properties of something's surface, or wavelengths of light, or anything of the sort; the colours I see when I hallucinate are mental phenomena, and it is acceptable to say that I see these colours. -

Direct realism about perception

I'll copy the argument from Epistemological Problems of Perception:

1. Nothing is ever directly present to the mind in perception except perceptual appearances. (Indirectness Principle) Thus:

2. Without a good reason for thinking perceptual appearances are veridical, we are not justified in our perceptual beliefs. (Metaevidential Principle)

3. We have no good reason for thinking perceptual appearances are veridical. (No-Good-Reason Claim)

4. Therefore, we are not justified in our perceptual beliefs.

The most minimal version of indirect realism is simply an acceptance of (1), where "directly present" is a substantial claim about phenomenology.

The more skeptical indirect realists may also accept (3), and so (4), although strictly speaking they can reject (3), e.g. if they agree with the naive colour realist that colours exist "out there" but disagree that these are ever directly present to the mind (the distinction I made in earlier posts between token and type identity).

And direct realists, in their attempt to argue that (4) is false, argue that (1) is false. -

Direct realism about perceptionIndirect realism, as you are presenting it, seems to depend on the idea that knowledge of the world is justified by first securing knowledge of phenomenal character and then inferring outward. — Esse Quam Videri

Then perhaps I haven't explained myself clearly, because indirect realism argues that because perception of the world is not direct (i.e. its features do not manifest in phenomenal experience) phenomenal experience doesn't justify our knowledge of the mind-independent nature of the world, hence there being an epistemological problem of perception. -

Direct realism about perceptionThey hear hallucinated voices. — Banno

Yes, and hallucinated voices are mental phenomena. Ergo, the thing being heard is a mental phenomenon.

The Common Kind Claim is that this sense of hearing voices also occurs in the non-hallucinatory case, i.e. in the non-hallucinatory case there is both hearing voices-as-mental-phenomena and hearing voices-as-distal-stimulus.

The indirect realist claims that it is only hearing voices-as-mental-phenomena that satisfies the philosophical sense of directness (as explained here) and that it is only in virtue of this that hearing voices-as-distal-stimulus is possible — hence the latter being indirect perception. -

Direct realism about perceptionAnd when you hallucinate, you don't see anything - that's kinda the point. — Banno

Arguing that schizophrenics don't hear voices, only hallucinate voices, is such a pointless argument that fails to address the actual philosophical substance of both direct and indirect realism. The phrase "the schizophrenic hears voices and sees faces in the walls" is a perfectly ordinary and acceptable phrase in the English language; it is meaningful, true, and does not entail anything like a homunculus.

This attempt to avoid the important phenomenological and epistemological issues by deferring to grammar or the dictionary, splitting hairs over the "one true" meaning of the verbs "see" and "hear", is hopelessly misguided.

You might want to use the phrase "I see X" only if there's the right kind of physical interaction between your body and some distal X, whereas others might want to use the phrase "I see X" whenever their visual cortex is active in the right kind of way, regardless of what, if any, distal causes there are. Even if it were a misuse of language to use the phrase "I see X" in this latter way, it does not follow that direct realism is true and indirect realism is false, because their dispute is far more significant (explained in my previous comment) than a dispute over which kinds of events are described by the phrase "I see X" in ordinary, everyday language.

And "I see X" ought not be conflated with "I directly see X". The philosophical term "directly" matters. Indirectly seeing distal objects is still seeing distal objects. So you appear to be guilty of equivocation in arguing that if you see the ship then you directly see the ship. -

Cosmos Created MindBut this view assumes that (1) the wavefunction is a real thing and (2) that consciousness is what is needed to cause the wavefunction collapse. — boundless

Well, I'd at least question the use of the phrase "is needed" in (2). If the wave function is real and quantum states really are in a superposition until something collapses them then that doesn't entail the binary choice between either a) only consciousness can collapse the wave function or b) only something other than consciousness can collapse the wave function. There's also c) consciousness and other things can collapse the wave function.

Maybe consciousness isn't special, but that doesn't mean it's ineffective. It's just as real and world-affecting as any other physical phenomenon, and maybe it (sometimes) does play a (non-unique) role in collapsing the wave function (if there is such a thing). -

Direct realism about perceptionYou’re treating phenomenal character as something like an epistemic instrument - a reading from which we infer how the world is, much like a thermometer reading. — Esse Quam Videri

On the view I’m defending, phenomenal character is not a “reading” at all. It is not truth-apt, not accurate or inaccurate, and not something whose reliability is assessed independently of judgment. — Esse Quam Videri

These are not contradictory positions.

It is both the case that (a) the phenomenal character of experience is not truth-apt and the case that (b) we use the phenomenal character of experience to make inferences about the environment. (b) is exactly what John and Jane do in the example I gave; their assertions about the wavelength of light emitted by the screen are not made apropos of nothing — they derive their conclusion from the phenomenal character of their experience (coupled with their knowledge of the wavelengths of light that are usually responsible for such an experience).

My view doesn’t require that phenomenal character be explained by an object’s qualitative property manifesting itself in experience. — Esse Quam Videri

But the naive realist does make this claim, and it is this claim that indirect realists reject. The naive realist believes that the phenomenal character of experience isn't just the phenomenal character of experience but also the phenomenal character of the environment. They believe that "there are in nature colors, of a distinctive kind that we are all familiar with, i.e., that colors are simple intrinsic, non-relational, non-reducible, qualitative properties ... not micro-structural properties or reflectances" and that our colour perception is veridical if and only if the phenomenal character of our experience is the same as the phenomenal character of the environment.

And I can sympathise with this naive view. It's tempting to imagine the world as literally being coloured in the exact same way that my experience is coloured (i.e. not just in the sense of reflecting certain wavelengths of light). I think even the non-naive realist thinks something similar with respect to geometry, i.e. shape, size, distance, orientation, etc.

But at least with respect to colour (and other secondary qualities, à la Locke), the world just isn't this way. Any inference about the mind-independent nature of the world from these secondary qualities is open to scepticism. That's really all there is to indirect realism. Often this goes hand-in-hand with the semantic claim that it's appropriate to say that we see and hear and feel and taste and smell these secondary qualities — something which those like Banno seem to object to — but I don't see this as philosophically relevant (e.g. this grammar doesn't entail anything like a homunculus). -

Direct realism about perceptionOn the view I’m defending, "phenomenal character" is not what John or Jane are making inferences about — Esse Quam Videri

I agree; they are making inferences about something in their environment. But they are using the phenomenal character of their experience to make this inference, much like someone might use a thermometer to make an inference about the temperature of a pot of water. If this isn't what you mean by "epistemic intermediary" then I don't really know what you mean by the term, and I'd argue that whatever you mean isn't a requirement for indirect realism to be true.

To put it in overly simple terms, the epistemic question that gave rise to the dispute between direct and indirect realism is "can we trust that the world is as it appears?", with direct realists answering in the affirmative and indirect realists answering in the negative.

To refer back to and extend my post to Banno above, the naive colour realist justifies their affirmation of the epistemic question by arguing that:

P1. Colours as manifested in phenomenal experience are of a distinctive kind that we are all familiar with, i.e simple intrinsic, non-relational, non-reducible, qualitative properties

P2. The character of phenomenal experience is explained by an actual instance of the apple's colour manifesting itself in phenomenal experience

C1. Therefore, apples are coloured in the distinctive kind that we are all familiar with, i.e simple intrinsic, non-relational, non-reducible, qualitative properties (... not to be conflated with micro-structural properties or reflectances, or anything of the sort)

Both the direct and indirect realist believe P1. The direct realist believes P2, and so deduces C1. The indirect realist rejects P2, and so cannot deduce C1, legitimising scepticism about the mind-independent nature of the world (i.e. C1 might be false).

So direct realism is true if and only if P2 is true and indirect realism is true if and only if P2 is false. My comments regarding resemblance or representation were just to say that indirect realism can be true even if C1 is true, although if modern science is to be accepted then it's clear that C1 is false, and so P2 must be false (hence why the Wikipedia article says "indirect perceptual realism is broadly equivalent to the scientific view of perception"). -

Direct realism about perceptionIn other words, this "something" needs to act as an epistemic intermediary rather than a merely causal intermediary, — Esse Quam Videri

So let's take the dress that some see to be white and gold and others black and blue. Let's simplify it for ease to a computer screen that some see to be red and some orange.

Do you accept that it is possible that all three of these statements are true:

1. John sees a red screen

2. Jane sees an orange screen

3. The screen emits only a single wavelength of light

I would say that it is possible that all three statements are true; the photo of the dress and the worldwide reaction to it suffices to prove this. So even though there is a sense in which John and Jane see the same thing (the screen) there's another sense in which they see different things (a red screen and an orange screen respectively).

In the context of (1), (2), and (3) all being true, it must be that the words "red" and "orange" are not referring to the wavelength of light emitted by the screen (which for the sake of argument I will say is 630nm, within what we would consider the "red" range). It is true that Jane sees an orange screen but it is not true that Jane sees a screen emitting a wavelength of light between 590nm and 620nm.

In the context of (1), (2), and (3) all being true, the words "red" and "orange" are referring to the phenomenal character of their experience. This phenomenal character is the "epistemic intermediary" from which they infer some mind-independent fact about the screen, with Jane (incorrectly) inferring that it is emitting a wavelength of light between 590nm and 620nm and John (correctly) inferring that it is emitting a wavelength of light between 625mn and 750nm. -

Cosmos Created MindHere's the problem of 'mixing' concepts of different contexts. Yes, the 'hard problem' is very relevant. But there is no compelling evidence that 'consciousness' has a special role in quantum mechanics. And even those who does give consciousness some kind of 'role' in quantum mechanics generally say that consciousness doesn't 'do' anything to physical reality. Rather, QM is a tool that is used to predict how the knowledge/beliefs of observers evolve in time. — boundless

It's not clear what you're saying.

Quantum mechanics is an attempt to describe the behaviour of all matter and energy in the universe. If consciousness exists and is a physical phenomenon then quantum mechanics can, in principle, explain the origin and behaviour of consciousness. And consciousness, like every other physical phenomenon in the universe, interacts with and affects the behaviour of its environment. So just as the physical phenomenon of electricity can "move" any surrounding matter — both at the quantum scale and the macro scale — so too can the physical phenomenon of consciousness.

It seems to me that to deny that consciousness plays a role in the behaviour of other physical phenomena is to either deny that consciousness exists or to deny that consciousness is physical (and so is some other kind of phenomena that is affected by but cannot in return affect physical phenomena). -

Direct realism about perception

This is a largely irrelevant semantic point but I don't think representation requires intention. If John and Jim are identical twins (or lookalikes) then I see no problem in saying that John's facial features are an accurate representation of Jim's facial features. It's not just a judgement we might make but also a (presumably) mind-independent geometric fact.

If you don't like the phrase "sensory content may or may not represent the environment" then perhaps the phrase "the sensory content's features (shape, size, distance, orientation, colour, etc.) may or may not resemble the environment's features".

The point I am making is that even if the environment has properties that resemble the properties that manifest in sensory experience, and even if English grammar describes the interaction between the body and the environment as "seeing the environment", if there is such a thing as sensory content distinct from the environment then it's still indirect realism. It is the features of this sensory content that inform our intellect and with which we make judgements about the environment, but given the distinction between this sensory content and the environment we cannot use sensory content alone to determine that it accurately resembles the environment (at best we can only determine that it is causally determined by the environment) leading to the exact epistemological problems that direct realists are trying to avoid — and in the extreme case to Kant's transcendental idealism.

We somehow need to "look past" sensory content to determine if it accurately resembles the environment. Some say that this is impossible in principle, whereas others say that modern technology has allowed us to do this, with such things as the Standard Model describing the mind-independent nature of the environment — but the picture of the world as described by the Standard Model (matter and energy as excitations of a quantum field) is very different to the world we are familiar with, proving, I think, that the original sceptical fears concerning the epistemological problem of perception were accurate.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum