-

jorndoe

4.2kSomeone dropped a hopelessly confuzzling argument on me, that I managed to extract a wee bit from, roughly as follows (formalization not included).

jorndoe

4.2kSomeone dropped a hopelessly confuzzling argument on me, that I managed to extract a wee bit from, roughly as follows (formalization not included).

It takes a strange and unusual outlook to assert that Moon rocks are sentient. Observations (and common sense for that matter), will have it that sentience is not a prerequisite for something to exist.

1. A world without sentience does not derive a contradiction. That is, among possible worlds some are without sentience. Sentience is not necessary.

2. By (our) definition, G is necessarily sentient. Conversely, a sentient entity is not necessarily (a) G.

3. If G's existence is necessary, then G carries sentience along to all possible worlds, so that sentience exists in all possible worlds, making it necessary by definition, which contradicts 1. (G figures at most in possible worlds with sentience. A necessary characteristic of a necessary entity, is itself necessary.)

4. Thus, G is not necessary.

Definitions of God that suppose God is necessary will have to consider exclusion of sentience thereof.

Possible worlds semantics at a glance:

- necessarily p ⇔ for all logical worlds w, p holds in w

□p ⇔ ∀w∈W p - possibly p ⇔ for some logical world w, p holds in w

◊p ⇔ ∃w∈W p

Some details: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Possible_world

All explanation, consists in trying to find something simple and ultimate on which everything else depends. And I think that by rational inference what we can get to that’s simple and ultimate is God. But it’s not logically necessary that there should be a God. The supposition ‘there is no God’ contains no contradiction. — British theologian Richard Swinburne, 2009 - necessarily p ⇔ for all logical worlds w, p holds in w

-

jorndoe

4.2kAt a glance, I see a couple objections:

jorndoe

4.2kAt a glance, I see a couple objections:

- outright reject modal logic

- solipsism, panpsychism (or some other special idealism)

It's trivial to come up with an idealist objection.

Suppose I'm a solipsist, holding that only whatever I'm certain of is the case (thereby conflating epistemology and ontology). My error-free knowledge extends roughly to the existence of (self)awareness and some (other) experiences, including sentience (perhaps depending a bit on what's understood by the term). Regardless of any modalities, my sentience becomes necessary.

It's already broadly agreed upon that solipsism is not deductively dis/provable. My self-awareness is essentially indexical, and noumena to any other (self)awarenesses. Phenomenological experiences themselves are "private", part of onto/logical self-identity and not something else.

So, there's no dis/proof to be found here, though obviously such sentiments has consequences that most folk find ridiculous, but there you have it, that's one objection.

Does a necessary God, that's necessarily sentient, imply idealism (well, or substance dualism or whatever)? -

Terrapin Station

13.8k

Terrapin Station

13.8k

The simple use of "G" rather than "God" confused me at first.

Anyway, someone who believed that God's existence is necessary would think that the first premise is false. -

unenlightened

10kIf G's existence is necessary, then G carries sentience along to all possible worlds, so that sentience exists in all possible worlds, making it necessary by definition, which contradicts 1. (G figures at most in possible worlds with sentience. A necessary characteristic of a necessary entity, is itself necessary.) — jorndoe

unenlightened

10kIf G's existence is necessary, then G carries sentience along to all possible worlds, so that sentience exists in all possible worlds, making it necessary by definition, which contradicts 1. (G figures at most in possible worlds with sentience. A necessary characteristic of a necessary entity, is itself necessary.) — jorndoe

I'm finding this one hard to make sense of. Why should God 'carry' sentience to all possible worlds? God creates a possible world consisting of, say, a piano, and not much else. Why does the piano have to be sentient? It looks as though there is the assumption of immanence??? -

Terrapin Station

13.8kI'm finding this one hard to make sense of. — unenlightened

Terrapin Station

13.8kI'm finding this one hard to make sense of. — unenlightened

He means that if in any arbitrary possible world (or in other words, if in all possible worlds), God is a necessary entity (for that possible world), then sentience obtains in that possible world.

The alternate idea is that in at least some possible worlds, God is not a necessary entity (which he's taking to mean that God is not a necessary entity period, which only follows if we define necessity to mean or imply necessity in all possible worlds, and we don't allow that something can be necessary in some possible worlds but not others). -

unenlightened

10kYes, that assumes immanence. There is a difference between necessary for, and necessary in, which you elide above.

unenlightened

10kYes, that assumes immanence. There is a difference between necessary for, and necessary in, which you elide above.

So God can be necessary in the sense of having to create a world without the created world being necessarily sentient. If God intervenes in the world to play the piano, then it is a different matter. -

Terrapin Station

13.8k

Terrapin Station

13.8k

Another way to ask it is, "Are there possible worlds where God doesn't exist?" And where we're contrasting that with the idea of whether God necessarily exists with respect to every possible world.

I think that the "in/for" distinction, while maybe it makes sense, is irrelevant to what the initial post is getting at. -

unenlightened

10kIt doesn't clarify to to substitute 'with respect to'. Compare...

unenlightened

10kIt doesn't clarify to to substitute 'with respect to'. Compare...

Necessarily, every work of art requires an artist, and necessarily, an artist must be sentient. But not necessarily is every work of art sentient, unless the artist participates in the work of art in such a way as to be present in it - as in performance art. This participation is what I am calling 'immanence' in God's case. -

Terrapin Station

13.8kNecessarily, every work of art requires an artist, and necessarily, an artist must be sentient. But not necessarily is every work of art sentient — unenlightened

Terrapin Station

13.8kNecessarily, every work of art requires an artist, and necessarily, an artist must be sentient. But not necessarily is every work of art sentient — unenlightened

Yeah, that works fine, but works of art are not (possible) worlds. -

unenlightened

10k... but works of art are not (possible) worlds. — Terrapin Station

unenlightened

10k... but works of art are not (possible) worlds. — Terrapin Station

They are for God. -

Terrapin Station

13.8k

Terrapin Station

13.8k

Presumably you mean that possible worlds are "works of art" for God (not that works of art are possible worlds for God). That's fine, too, but it is irrelevant to what (possible) world means logically. If a God (necessarily) exists "for" that possible world to exist then God (necessarily) exists with respect to that possible world, which is the same, in logic, as saying that he exists "in" that possible world.

I think you're confusing an issue of ontological types/ontological hierarchies with simple inventories of everything of or pertinent to a domain. (The latter is what (possible) world talk is about). -

Barry Etheridge

349

Barry Etheridge

349

What does it mean to say that God is sentient? If it has any meaning at all it clearly cannot be sentience as we know it. And even if it were it seems an awfully big leap from every possible world has a sentient being involved in some kind of a relationship with it to all possible worlds have sentience and further still to all possible worlds are sentient. -

jorndoe

4.2kAnyway, someone who believed that God's existence is necessary would think that the first premise is false. — Terrapin Station

jorndoe

4.2kAnyway, someone who believed that God's existence is necessary would think that the first premise is false. — Terrapin Station

Sure, but that's a tad bit presumptuous, implausibly strong, unjustified, especially in comparison to any number of alternatives.

Consider a rather simple world consisting in one zero-dimensional "thing", that's indivisible, and changeless, and that's about it. Can you derive a contradiction from that? Not particularly interesting, but seemingly consistent nonetheless.

I'm finding this one hard to make sense of. Why should God 'carry' sentience to all possible worlds? God creates a possible world consisting of, say, a piano, and not much else. Why does the piano have to be sentient? It looks as though there is the assumption of immanence??? — unenlightened

That's not quite how possible worlds semantics work.

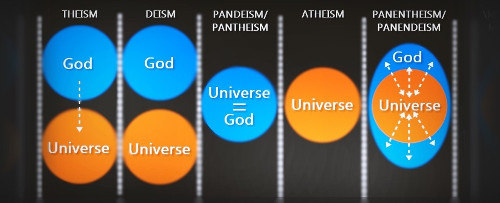

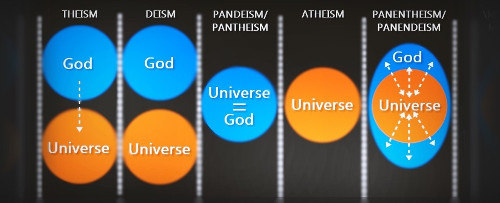

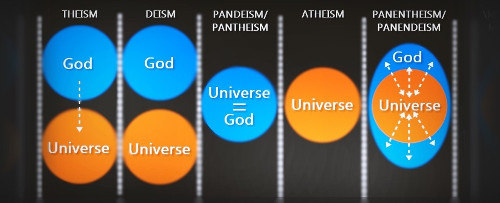

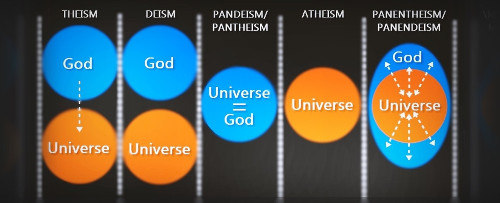

A possible world is an inclusive entirety, where ordinary logic holds. Here are some suggestions, e.g. deism (ignore the simplicity, it's just for illustration):

A significantly simpler suggestion is the zero-dimensional "thing" above, which does not need sentience (or sentient entities) to be logically consistent, non-contradictory. -

jorndoe

4.2kWhat does it mean to say that God is sentient? If it has any meaning at all it clearly cannot be sentience as we know it. And even if it were it seems an awfully big leap from every possible world has a sentient being involved in some kind of a relationship with it to all possible worlds have sentience and further still to all possible worlds are sentient. — Barry Etheridge

jorndoe

4.2kWhat does it mean to say that God is sentient? If it has any meaning at all it clearly cannot be sentience as we know it. And even if it were it seems an awfully big leap from every possible world has a sentient being involved in some kind of a relationship with it to all possible worlds have sentience and further still to all possible worlds are sentient. — Barry Etheridge

Well, defining sentience in terms of something else is perhaps somewhat futile.

I'm thinking it's part of mind, where mind is an umbrella term for self-awareness, consciousness, thinking, feelings, phenomenological experiences, qualia, the usual.

Let's just say "sentience" as we know it, since, what else would we be talking about...?

I suppose we might come up with some special kind of "sentience", but then we're already starting to move into the thick fog of London on a dark night, a bit like inventing things for the occasion. :)

(Sometimes I've seen sentience referring to an awareness of one's own sentiments, feelings, reactions and such, as distinct characteristics of oneself, quite close to self-awareness, something along those lines, but that may not be spot on.) -

Emptyheady

228Claiming God's existence and solipsism is such a strange combination.

Emptyheady

228Claiming God's existence and solipsism is such a strange combination.

Casting that aside, any discussion regarding God's existence without coherently justifying and clarifying "God" is not worth having.

The Modal ontological argument is still very controversial with an unsound premise regarding the possibility of a maximal great being/sentient. Is it possible for a maximal great being/sentient to exist at all? Doesn't it conflate logical possibility with metaphysical possibility? If somehow, you pass the ignosticism test of defining God, why does it make God's existence metaphysically unobjectionable.

I believe that even Plantinga admitted that it isn't proof of God's existence -- though his epistemological basis is quirky, something I still don't quite grasp. -

jorndoe

4.2kClaiming God's existence and solipsism is such a strange combination. — Emptyheady

jorndoe

4.2kClaiming God's existence and solipsism is such a strange combination. — Emptyheady

Good point (I suppose, unless the solipsist consider themselves God).

Perhaps subjective idealism, à la Berkeley or something similar, is a better example.

Or panpsychism of some sort, one that starts from a particular sentiment already contrary to 1.

Come to think of it, if the argument above is sound, then it would seem contrary to Plantinga's modal ontological argument.

Anyway, in this context, I'd say 1 (the zero-dimensional "thing", for example) is significantly more plausible than the contrary. -

Terrapin Station

13.8kSure, but that's a tad bit presumptuous, implausibly strong, unjustified, especially in comparison to any number of alternatives.

Terrapin Station

13.8kSure, but that's a tad bit presumptuous, implausibly strong, unjustified, especially in comparison to any number of alternatives.

Consider a rather simple world consisting in one zero-dimensional "thing", that's indivisible, and changeless, and that's about it. Can you derive a contradiction from that? Not particularly interesting, but seemingly consistent nonetheless. — jorndoe

If one believes that God's existence is necessary for any possible world would think that a world that consists solely of a single simple that's not God is impossible.

I actually think that a world with a single "zero-dimensional thing" is incoherent, by the way, and I'm an atheist. That's simply because I don't believe that there can be zero-dimensional things. -

jorndoe

4.2kIf one believes that God's existence is necessary for any possible world [one] would think that a world that consists solely of a single simple that's not God is impossible. — Terrapin Station

jorndoe

4.2kIf one believes that God's existence is necessary for any possible world [one] would think that a world that consists solely of a single simple that's not God is impossible. — Terrapin Station

Right, yet that's just a definitional petitio principii.

By assertion a world without sentience is impossible because G is absent therefrom, because G is necessary (by definition), which, by the way, holds for any G.

I actually think that a world with a single "zero-dimensional thing" is incoherent, by the way, and I'm an atheist. That's simply because I don't believe that there can be zero-dimensional things. — Terrapin Station

For worlds like ours, by a physical/epistemic/nomological assessment, I tend to agree (no two-dimensional superstrings either per se).

Metaphysically, maybe, maybe not.

Logically it seems non-contradictory to me.

(It was just a (very) simple example that came to mind; not the best.) :) -

Terrapin Station

13.8kBy assertion a world without sentience is impossible because G is absent therefrom, because G is necessary (by definition), which, by the way, holds for any G. — jorndoe

Terrapin Station

13.8kBy assertion a world without sentience is impossible because G is absent therefrom, because G is necessary (by definition), which, by the way, holds for any G. — jorndoe

Wait--that's not actually stated as an argument, so it can't be an example of petitio principii. An argument for this might be something like: If God is a necessary being in all possible worlds, then a world without sentence isn't possible. God is a necessary being in all possible worlds. Therefore a world without sentience isn't possible.

That's a simple modus ponens. -

unenlightened

10kA possible world is an inclusive entirety, where ordinary logic holds. Here are some suggestions, e.g. deism (ignore the simplicity, it's just for illustration): — jorndoe

unenlightened

10kA possible world is an inclusive entirety, where ordinary logic holds. Here are some suggestions, e.g. deism (ignore the simplicity, it's just for illustration): — jorndoe

Well if God, then all of these are possible worlds except the atheist world. But it still seems to me that God only necessarily carries sentience into worlds he enters: 1 & 3.

Otherwise, if one wishes to say that a universe without sentient beings is still a sentient world because 'God knows', then one simply accepts the fact, and rejects premise one.

Always and everywhere God, therefore a non-sentient world is a contradiction. Which no longer requires that a piano is sentient. -

Terrapin Station

13.8k

Terrapin Station

13.8k

That's a handy illustration as it much more easily shows what I earlier labeled a confusion that was occurring: the possible worlds in each of those is ALL of the stuff that we see both horizontally and vertically between the "white lines." I believe that you () were thinking of "possible worlds" as referring to ONLY the circles that are labeled "universe." It's likely confusion simply due to the word "world." "World" in this situation simply refers to EVERYTHING between those white lines. It's not a term for the "material universe" or anything like that. -

jorndoe

4.2k@Terrapin Station, I just meant that obviously you can deny 1 as follows:

jorndoe

4.2k@Terrapin Station, I just meant that obviously you can deny 1 as follows:

a. definition: G is necessary

b. definition: G is necessarily sentient

c. ... sentience is present for all logically possible worlds ...

d. 1 is wrong

And some do just that, albeit contrary to Swinburne.

My line of thinking was that it seems rather odd to assert G, and deny 1 on that account, when much simpler worlds come through as non-contradictory.

@unenlightened, I think @Terrapin Station has the notion of "possible world" well illustrated.

A logical world is an all-inclusive, complement-free entirety (all, "everything") where ordinary logic holds.

Like in the illustration, the whole deism column is a suggestion of a possible world (God and Universe). -

Michael

16.9kDefinitions of God that suppose God is necessary will have to consider exclusion of sentience thereof. — jorndoe

Michael

16.9kDefinitions of God that suppose God is necessary will have to consider exclusion of sentience thereof. — jorndoe

Depends on the kind of necessity. Metaphysical necessity is not the same as logical necessity.

As a possible example (correct me if I'm wrong), it doesn't seem to be a logical necessity that the angles of a triangle add up to 180 degrees (in Euclidean geometry), but it is a metaphysical necessity. -

unenlightened

10kA logical world is an all-inclusive, complement-free entirety (all, "everything") where ordinary logic holds.

unenlightened

10kA logical world is an all-inclusive, complement-free entirety (all, "everything") where ordinary logic holds.

Like in the illustration, the whole deism column is a suggestion of a possible world (God and Universe). — jorndoe

In which case, if necessarily sentient G. then necessarily sentient world is trivial. -

jorndoe

4.2kI suppose, then, as far as assertions go, there's a mutually exclusive choice between 1 and a,b:

jorndoe

4.2kI suppose, then, as far as assertions go, there's a mutually exclusive choice between 1 and a,b:

- 1. Among possible worlds some are without sentience. Sentience is not necessary.

- a. Definition: G is necessary.

b. Definition: G is necessarily sentient.

The former (1) might be exemplified by some simple worlds while assuming they're non-contradictory, whereas the latter (a, b) assumes G and consistency.

OK, let me try being a bit more concise...

Possible worlds semantics at a glance:

• necessarily p ⇔ for all logical worlds w, p holds for w

• □p ⇔ ∀w∈W p

• possibly p ⇔ for some logical world w, p holds for w

• ◊p ⇔ ∃w∈W p

So, a logical world is an inclusive, complement-free entirety where ordinary logic holds.

Let's just say this is ordinary logic (catering for intuitionist/constructive logic), the three first in particular:

1. identity, x = x, p ⇔ p

2. non-contradiction, ¬(p ∧ ¬p)

3. the excluded middle, p ∨ ¬p

4. double negation introduction, p ⇒ ¬¬p

5. modus ponens

6. modus tollens

Ontology and logic tend to meet at identity.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum