Comments

-

God as the true cogito

The most effective refutation of such kinds of ontological arguments that I know of is the one invented by Kant: existence is not a predicate, or if you prefer Frege: existence is a second order predicate.

If that is true, then it makes no sense to think of existence as a “quality which is better to have”:

Suppose I express my idea of a blue apple by painting a picture of five blue apples. I point my finger at it and say, "This represents five blue apples." If later I discover that blue apples really exist, I can still point to the same picture and say, "This represents five real blue apples." And if I can't discover the existence of the blue apples, I can point to the painting and say, "This represents five imaginary blue apples." In all three cases the picture is the same. The concept of five real apples does not contain one more apple than the concept of five possible apples. The idea of a unicorn will not get more horns just because unicorns exist in reality. In Kant's terminology, one does not add any new properties to a concept by expressing the belief that the concept corresponds to a real object external to one's mind. — Martin Gardner

Here is a (short) explanation of Frege's criticism -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

The world is a phenomenon, an object of experience, now that we’ve witnessed it in its entirety from outside its limits; the universe is not. If the universe is the condition for space and time, it cannot be a phenomenon determined by them. Trying to equalize them, is, as the Good Professor says, “...a mere subterfuge...”, nevermind the lengthy exposition on why this is so. — Mww

Ok, so according to this distinction the universe is never experienced as a phenomenon, unlike the world, right?

You say that we've witnessed the world in its entirety, but then what do you make of philosophers and physicists who speak of unknown parts of the world, and parts we have not observed yet or of whose existence we are not even aware at present? If those are part of the world, surely it can't be said that we've witnessed the world in its entirety.

On the other hand, if we define the world as all the phenomena we've experienced and whose existence we're currently aware of, then I agree that it must have had an origin in time (though I'm not sure about that being an analytic truth).

How the universe has a necessary origin in time? Hmmmm.....two ways, perhaps. Show the origin of the universe is simultaneous with the origin of time, — Mww

That would mean that the universe “begun to exist” (so to speak) “at the same time” as time. But I thought that the universe, according to you, was the condition for space and time, in which case wouldn't that imply that the universe is determined by time, contrary to what you said? I thought only phenomena could have origins in time, meaning the universe, as you defined it, would have no origin in time.

Also, that would seem to imply that there was time before the origin of time (for how else would the universe originate at the same time as time?), which is surely absurd.

Or else what do you mean by “origin in time” when speaking about the universe? -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

Argument A

1. It makes sense to ask about a time before any given moment in time — TheMadFool

If there is no beginning in time, then yes.

2. If it makes sense to ask about a time before any given moment in time then, the past is infinite — TheMadFool

If 1 is true, then yes.

Ergo,

3. The past is infinite [1, 2 MP] — TheMadFool

That does follow if 1 and 2 are true.

Argument B

4. We are in the present, the now

5. If we're in the present, the now and the past is infinite then, the infinite past (has passed) is an actual/completed infinity — TheMadFool

If the past is infinite, then the infinite past is an actual/completed infinity, if by that one means merely that it is the case in reality. But that does not imply that an infinite amount of time has “passed” up to the present moment.

For I ask: From/since when to when did it pass? You can't say “From the beginning of the universe to the present day”, Because there is no “beginning of the universe” in this model.

And if you say, it passes from some moment in the past that wasn't the beginning up to the present moment, then a finite amount of time has passed, not an infinite amount, and that poses no problems.

You're bothered by how if the past is infinite, time has no beginning and ergo, you contend that time couldn't possibly pass. This, if you really think about it, is just another way of expressing the idea that the past is finite. — TheMadFool

No, did you read my OP? I'm trying to show that there is nothing logically inconsistent about a universe with an infinite past, against what Kant tried to “prove” with one of his theses.

I'm saying an infinite amount of time has not “elapsed”, but also that that doesn't contradict a universe with an infinite past.

In other words, there has to be a beginning for time = the past is finite. Simply put, a petitio principii - you can't claim the past is finite because the past is finite. — TheMadFool

No, what I'm rejecting is Kant's argument which states that the universe couldn't have been infinite towards the past because that would imply that an infinite amount of time would have elapsed up to to the present moment.

That one would be the one that begs the question, by assuming tacitly that the universe must have had a beginning in time: It assumes that such an infinite universe both has and doesn't have a beginning in time, which is just a way of creating a strawman of the person who holds that the universe is infinite towards the past.

As for the passage of time, we're here, in the now, right? Considering the past is infinite (see proof above) and we're here, in the now, time has passed. — TheMadFool

If you look at my previous posts again, you'll see that I don't have a problem with the idea of time passing, but with the idea that “if the universe has an infinite past then an infinite amount of time must have passed”.

So, if you are saying that, that's what I'm rejecting.

But if you insist: From/since when to when did it pass? It must have passed from some moment in time to some other moment in time, right? -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

If you are not using the words “world” and “universe” as synonyms, then what's the difference between the two?

I said that the world exists and therefore has a necessary origin in time, is a tautology, a analytic truth. — Mww

Right, but that would mean that we could deduce the proposition “The world has a necessary origin in time” without experience, merely by analysis of the concept “world”, right? I don't think that's the case, but maybe you could show me how that proposition is analytic. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

The solutions to the field equations support it, which are not subject/copula/predicate propositions, but mathematical formulations, and while not analytical, are nonetheless true. If otherwise, the entire human system for knowledge certainty is in serious jeopardy, regardless of its adaptability to changes in observational data. — Mww

Ok, but you said before that it was a tautology, which seems untrue: the universe is not by definition finite towards the past, which would be the case if you could deduce that from the definition of “universe” alone, there would be no need for empirical observation. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

The past is infinite and an actual infinity at that; after all, we're at some point in time (this now) that can be only if infinite time did pass [another way of saying completed/actual infinity]. — TheMadFool

But when someone says an infinite amount of time “passes”, if they don't mean that it passes from some moment in time to some other moment in time (which clearly cannot be the case), then I do not understand what is meant by “passing”. In the case of a universe with an infinite past, the idea that time must “pass” from a beginning moment all the way to the present seems false, since by definition such a universe has no beginning moment:

The statement that the universe cannot be infinite towards the past because that would imply going through or traversing an infinite number of events to get to the present seems false to me, since it seems to assume that in traveling such a series of events one goes through or traverses from an initial moment to the present, while this infinite universe towards the past by definition has no initial moment.

If, on the contrary, the journey begins at some point in the past which is not an initial moment, it does not matter how much one goes back in the timeline, the events and time from that moment to the present will always be finite, and there is therefore no impossibility in a universe whose time is infinite to the past.

And it makes no sense to say "but the journey begins before the temporal events begin", because there is no point in time in which they begin according to this model (again, by definition). — Amalac

I like what you said :point: "...if being "completed" means that one must be able to write down all the elements of the series..." I think you're on the right track. — TheMadFool

If that's what you mean, that what's your response to this?:

If being “completed” means that one must be able to write down all of the elements of the series, then why should we accept that criterion as the one which determines whether a series of elements can “exist” or not? — Amalac

Meaning: Why is whether it is “enumerable” or not the way to determine if it's possible or not? -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

For what it's worth, to think there's a problem with an infinite past in the sense such can't be for the simple reason that infinite anything can't be completed is to assume Aristotle's position that there are only potential infinities and no actual infinities.

It's quite clear why Aristotle thought that way; after all, the definition of infinity is such that the very notion of completion/an end is incompatible with it.

The only supposedly actual infinity I'm aware of is the set of natural numbers {1, 2, 3,...} but then it's an axiom [something arbitrarily assumed as true]. — TheMadFool

What about the series of negative integers? It has no first term of course, but it ends in -1, so that it is “completed” in that sense. Why can't the timeline of the universe be like that (with -1 being the present, so to speak)?

If being “completed” means that one must be able to write down all of the elements of the series, then why should we accept that criterion as the one which determines whether a series of elements can “exist” or not? -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

Evidence that the universe is finitely existent in the past is provided by the mathematically logical necessity of singularities. — Mww

If you have to look for evidence in support of that proposition, then it's no longer a tautology. It may be logically necessary given the laws of physics that govern the actual universe, but these laws themselves are not logically necessary (as in: they could have been different, and could even change in the future).

As for singularities, if you are talking about gravitational singularities, then I guess you are refering to the Big Bang being one.

Well, I seem to remember that some scientist (was it Sean Carroll? Lawrence Krauss?) said that the Big Bang is a sort of placeholder for our ignorance, the limit to how far back we can know the cosmos.

There are some things that are not too clear to me: Is the Big Bang the cause of the observable universe? Or is it the cause of the universe in an absolute, all-encompassing sense (both the observable and the unobservable universe)?

Because I'm refering to the universe in the second, all-encompassing sense.

Now, I know some people say that time “appeared”, so to speak, with the Big Bang, but that seems problematic to me for many reasons, one of them being that it is not clear that time actually exists outside our minds, and if it doesn't exist outside our minds then there is no sense in saying that time appeared with the Big Bang, since in that case time “appeared” when the first subject who imposed time onto what he perceived appeared. Such was Kant's point of view, for instance.

I don't know how we could know if time exists outside of our minds or not.

Thing is, experience informs us of the phenomenal reality of the world, but cannot inform us of the phenomenal reality of the universe or of singularities. Can’t use the criteria for what it is possible to know, in determinations for what is not. — Mww

Maybe here is where I misunderstood you, I thought you were using the words “world” and “universe” as synonyms.

But I agree with Kant's conclusion: there is no sense in asking such questions about the universe as a whole. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

That the world exists and therefore has a necessary origin in time, is an analytic...tautological....truth of logic, insofar as its negation is impossible. — Mww

Seems to me like that would only be true if the universe were finite towards the past, which doesn’t seem tautologically true, since if it were, no philosophers or physicists would argue about it: they would all agree that the universe is finite towards the past.

Or perhaps I’m misunderstanding and you are talking about the other thesis, which holds that the universe did have a beginning, in which case yes: by definition it does, but only because Kant assumes for sake of argument that it does have an origin in time, to show how that assumption leads to a contradiction, as well as the antithesis which holds that it doesn’t have an origin in time. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

The realist interpretation of potential infinity is that it is epistemic ignorance of the value of a bounded variable. For the realist an unobserved variable has a definite value irrespective of it's measurement or observation . Hence for the realist, the value of a variable is either actually infinite or it is finite, with no third alternative. — sime

Ok, I'm fine with this.

The logic of a potentially infinite past in this constructive sense is superficially demonstrated in the video games genre known as "roguelikes", where a player assumes the role of an adventurer who explores a randomly generated dungeon that is generated on the fly in response to the player's actions. — sime

Hmm, ok.

So it's sort of like the universe, in the sense that it is constantly expanding. But supposing one could “catch up” to the expansion (in some possible world), would there be anything beyond the expansion, or would space somehow “end” there? (maybe I'm just very confused about this matter).

By asymmetric causality, I am referring to either the belief or definition of causality such that causes come before their effects. This is a physically problematic assumption due to the fact that the microphysical laws are temporally symmetric. — sime

I'll plead ignorance about this point, I don't know enough physics to comment on that.

But I guess my point is that the notion of “cause” may not be applicable to the total, as Russell pointed out in his famous debate with Copleston.

If we see the universe as a “set” or “collection/bundle of events”, then there may be no sense in asking what its cause is, just as there is no sense in asking what the cause of “the set of all ideas” is, in the same sense as we would ask what the cause of a rock, or of lightning, is.

But then again, Russell did also say that matter could be seen as a way of grouping events into bundles, so maybe there is a sense in asking for the cause of sets after all. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

With respect to Kant reflected in Popper, the world exists, which makes explicit a necessary origin in time — Mww

Doesn't seem that explicit to me, how does that follow? (1. The world exists, 2.???, 3. Therefore, the world has an origin in time)

Where do he prove that, exactly? — Mww

I meant as in “apparently prove”, since by Kant's reasoning one can also “prove” that the universe cannot be finite towards the past.

So the conclusion of the antinomy is that there is no scientific sense in the very question: “is the universe finite or infinite towards the past?”, right?

But my point was that even his “apparent proof” seems invalid. -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?I did, I thought the argument seemed fallacious, but figured maybe I was making some obvious mistake in the argument one of you in the forum could point out.

-

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

The idea of an actually infinite past in the extensional sense of actual infinity is incompatible with the beloved premise of asymmetric causality running from past to future. — sime

Could you elaborate a bit on how it's incompatible with asymmetric causality? I'm not very well acquainted to the idea.

In order to accept the premise of an actually infinite past, one must both theoretically reverse the direction of causality and somehow square that against physics and intuition — sime

If by “reversing the direction of causality” you mean that we must go back into the chain of causes and arrive at a first cause, why must we? Doesn't that already assume that the universe must be finite towards the past, and thus beg the question?

Whether or not it contradicts our intuition, that is no ground for rejecting physical models with an actual infinite past, since many physical discoveries also contradict our intuitions and are nonetheless true.

and in addition posit a finite future - a situation that is at least as problematic as the original picture. — sime

I mean, it's currently finite towards the future (up to the present moment).

Whether time has an absolute end at some point in the future I do not know, though physicists assure us that the universe very likely will come to freeze completely (such is one of the most plausible theories at present anyway).

I guess one could argue that even in such a completely static universe, time still passes, in which case the future time would be infinite.

But at any rate, why would an infinite future, in the sense I have described, be incompatible with an infinite past?

In physics , the notion of actual temporal infinity is metaphysical in the literal sense of meta-physics, i.e it is a proposition that cannot be falsified, verified or even weakly evaluated through experiments. — sime

Here I probably agree with you: I don't see how such a proposition could be falsified.

However, there cannot be any empirical evidence on the basis of the observable universe to posit a past of any particular length. Therefore, the idea of a potentially infinite past is both perfectly consistent and the least assuming position to adopt. — sime

Hmm, I'm kind of puzzled with regards to this idea of a universe with a “potentially infinite” past.

I mean, the past is either finite or it's infinite, right? What is meant by “potentially infinite” then? -

Can the universe be infinite towards the past?

How do you imagine negative time for yourself? — SimpleUser

I suspend judgement as to the question whether time had an absolute beginning or not.

Kant spoke of time, which clearly has a beginning and is always positive. — SimpleUser

In this antinomy, Kant considered a universe which is infinite towards the past, which by definition has no beginning, and argued that it is logically inconsistent. Leaving aside the fact that later he argued that we cannot apply the notions of space and time to things that we do not experience (which I think is correct), i.e. the universe as a whole, my point is that the argument he used to prove that the universe cannot be infinite to the past doesn't appear valid regardless. -

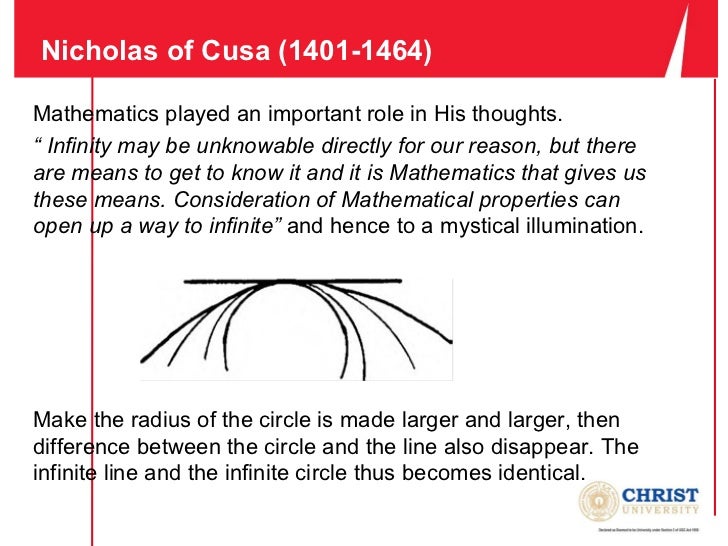

Question about the Christian TrinitySpeaking of math and the Trinity, a more interesting attempt was made by Cusanus: Suppose you have an isosceles triangle in which two of its equal sides gradually became longer and longer.

Then, Cusa argued, a triangle that had sides which were infinitely long, would be an infinitely long straight line. That is because the longer the sides of the triangle become, the closer it gets to becoming a straight line.

That is how he explained, metaphorically, how 3 and 1 could be the same.

It's easier to understand with an infinite circle, which is also the same as an infinite line according to Cusa:

-

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)The developers are quite literally the AIs gods. All the problems we have of understanding why God can not reveal himself to us, are made clear by this analogy. A creator is all powerful and omnipotent, yet unable to show their face to the AI. — Edy

That's another way of putting it, yes.

But the point seems to be the same: the non-physical cannot mix with the physical without ceasing to be non-physical. Or if it could, it seems hard to imagine how such a thing is possible (and how could we identify something non-physical in the physical world?)

On the other hand, both the developers and the game are physical, so the former have no problem creating the latter.

With God however, the matter is different: Assuming God did exist then how did he, a non-physical entity, create the physical universe? That seems inconceivable, to say the least.

So I think your analogy is not quite adequate in that respect. -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)Calculus uses infinite points to describe something that is also finite in the exact same respect. — Gregory

Infinite parts ≠ infinite extension. So no, it's not the “exact same respect”.

For instance: 1= 1/2+1/4+1/8+1/16+... even though 1 is a finite number, it has infinitely many parts.

We can divide a square in half, and then its half in half, and so on forever. And yet the square is obviously finite in extension.

Lots of things in modern mathematics seems to contradict Aristotle's law from one side — Gregory

Such as?

Another better law is that a human cannot name something in particular he knows for sure is impossible. — Gregory

Why not?

But anyway, as you said, let's not get off topic. -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)

If you are asking about Wittgenstein then yes, I am quite sure. If you are talking about theology then in my opinion God is ineffable and theologians are always in one way or another always trying to eff him. — Fooloso4

Ok then.

He is taking you to task. Trying to get you to think. Can you say what an illogical world would look like? Do you not see the problems? — Fooloso4

Right, and so one possible interpretation is that an “illogical” world is simply impossible, therefore even God cannot do what is logically impossible. I can't imagine X, therefore X is impossible. What's wrong with that interpretation?

Why is it important? You can create any God you want, one that is and one or more that is not constrained by logic. — Fooloso4

Because if, for instance, you showed a theologian a conclusive refutation of that God's existence (one bound by logic), then there would be no point in them thinking about what consequences could be derived from a philosophical system which falsely assumed that such a God can exist. And so, they could instead spend time on something more worthwhile.

It's opportunity cost, as economists say.

The argument is in my opinion not worth talking about. You obviously see things differently. — Fooloso4

Well, nothing to do about that I guess. -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)

If he exists, he made something that is both a particle and a wave; and to account for it we simply changed the description to one of mathematics. We choose the logic - the grammar - to match what is before us. — Banno

That doesn't answer my questions (unless in your sentence particle means exactly, and without equivocation, “not a wave”, is that what you are saying?), just answer “yes” or “no”:

Could God, if he exists, make something that both is and is not a tree, in the same sense and at the same time? Could he make an object that was both round and triangular? — Amalac -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)God is outside the logical relationships of things in the world. What is or is not logically possible has nothing to do with God. — Fooloso4

Are you sure about that?:

It used to be said that God could create anything except what would be contrary to the laws of logic. The truth is that we could not say what an "illogical" world would look like. — Wittgenstein

How would you interpret that passage? Many philosophers in the past and still now hold that God is constrained by logic, so it's still important to show why they are wrong, if indeed they are wrong.

Anyway, like I said before, we shouldn't focus on whether Mr's arguments are wholly consistent with Wittgenstein's philosophy, rather we should focus on the arguments for their own sake. -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)

So what difference will it make to what you do? Apart from posts to philosophy forums, that is. — Banno

By that criterion, you could ask the same about almost all philosophy.

God can't be "bound" by logic; logic is just formal grammar - how we can say things — Banno

Could God, if he exists, make something that both is and is not a tree, in the same sense and at the same time? Could he make an object that was both round and triangular?

If your answer to those questions is yes, then you are right that we should stay silent.

But it's still important in my opinion, because if this proof (Mr.S') were valid, then many philosophers could just stop wasting their time in building complicated systems based on a God that cannot do what is logically impossible, and use that time for more fruitful endeavors. -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)I mean... the ”consequence”, if one adopts the view that God is bound by the laws of logic, could be that such a God does not exist. I think that's a pretty important consequence, but if you don't agree that's fine.

-

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)

but since the questions do not ask anything, the answers can be of no consequence. — Banno

Let's just agree to disagree about this point then. -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)

Right, but I'm asking if it's even logically possible.

Also, sorry for lying but due to your answer I need to ask a few more questions:

If a transcendental God exists but didn't create the universe, what would be the explanation of the existence of said universe?

Would that universe be logically posterior or logically simultaneous to God? Are those options even possible?

Because if that's not logically possible, the rest of Mr.S' argument seems to follow. -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)

I'm not denying that......and yet there it is. — Banno

Anyway, one last question: do you think it is possible for God and the universe to exist, but also that God didn't create the universe? -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)

and yet there it is. — Banno

But that's precisely the point, he's saying that if his logic is correct and even God must obey the laws of logic (If God exists, the physical world must not exist, since it could only exist by being created by God, if God exists), then:

If God existed, the physical world would not exist. The physical world is ontologically incompatible with the nature of God. A single particle of the transcendental (of ethics, for example) would serve to crumble the entire universe. But, the physical world exists. Ergo: God does not exist. — Mr.S

And if we hold the view that God can do even what is inconceivable or unimaginable to us, then we should go back to mystical contemplation and stay silent. -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)Ok, so we are pretty much in agreement.

However, what about the question: if God exists, how did he create the world? Would you say we should also just stay silent about that?

It seems to me that Mr.S tries to argue: If creating the universe didn't involve mixing the physical with the metaphysical (which he holds is logically impossible), then creation is inconceivable/unimaginable. Therefore, creation is impossible.

But if God couldn't create the world, it would not exist. That contradicts the fact that the world does exist. Therefore, God does not exist.

Would you say that we can't argue: X is inconceivable/unimaginable, therefore X is impossible? -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)

Ok, but if you go back to the OP, you'll see that one of Mr.S' point is that the process through which God created the world (if he existed) is inconceivable, and that the existence of the world is ontologically incompatible with God's existence:

If God existed (which in itself remains to be seen), there would also be an unfathomable gulf between his greatness, his omnipotence, his spirituality and his ability to access the material world. It is assumed here, of course, that God is not matter (he is immaterial), since if he were subject to physical laws he would be a decadent God, an absolutely powerless God, a hoax of a God. In other words, despite his omnipotence, he cannot infiltrate matter, into the physical world in which we live, so he remains an alien God, from another plane. This leads me to a devastating conclusion on the theological-metaphysical plane:

If God existed, the physical world would not exist. The physical world is ontologically incompatible with the nature of God. A single particle of the transcendental (of ethics, for example) would serve to crumble the entire universe. But, the physical world exists. Ergo: God does not exist. — Mr.S

And even if God did exist, Mr.S would continue, he might be unable (due to a logical impossibility) to reveal his divine commands and what he wishes us to do, in the world.

And if that's the case, revelation through any sacred scriptures and miracles would be logically impossible.

God would remain forever unknowable, even if he did exist. “Only something Supernatural can express the Supernatural”, I think Wittgenstein said. -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)

Many statements we make have many meanings. — Gregory

Right, and to use a word with two different meanings without clarifying them is to commit the fallacy of equivocation, just as you have done here (if you think the following is a contradiction):

If I am in a doorway, I am both in the door way and in the room I'm stepping into. — Gregory

Aristotle was clear in his formulation of the Law of Contradiction: contradictory propositions cannot both be true in the same sense at the same time.

I would just suggest reading about Jains's seven values logic if you are interested in Hegel's style of argument. That's a good place to start — Gregory

Thanks for the advice, I'll read that when I have the time. -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)

You neglect consideration of an existential relationship. — Fooloso4

Could you elaborate?

Is this a concept of God that Wittgenstein endorsed? — Fooloso4

I don't know, he did say that God does not reveal himself in the world. But Mr.S doesn't want to defend the whole of Wittgenstein's philosophy, he only borrowed some of his ideas (as he interprets them) to make his argument. So see it more as Mr.S' conception of a trascendental God.

I suggest that if your concern is with Wittgenstein then stick with what he said rather than concepts he does not explicitly ascribe to. — Fooloso4

Well, that's how Mr.S interprets him. Let's not focus on who said what and who didn't, and more on the ideas themselves (like the validity of Mr. S' argument). -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)That's just a very poor choice of word. A Doctrine, creed, dogma... the implication of explicit rules. — Banno

Right, english is not my mother tongue, so you'll have to forgive me about this one. I thought “doctrine” could mean something similar to “theory”. But surely you must have realized that that is what I wanted to say. Let's not make this a discussion about words.

It's not that he does not reveal himself, but that if he exists he must be obvious. — Banno

How could the existence of a transcendental God be obvious though? Through some argument perhaps, but then how can language, which is the product of physical processes, apprehend the metaphysical?:

A two-way problem arises in this relationship of God with the empirical world:

(1) Upwards: the possibility of language to grasp the transcendental.

(2) Downwards: the possibility of the transcendental to infiltrate, to penetrate the world.

A problem, I repeat, that has two courses of action, being double in nature: first, the possibility that a physical language, that a factual thought, that a thought that is matter captures the transcendental; second, that from a thought or better still from a transcendental idea there is room for the possibility of penetrating the physical world — Mr.S -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)

That's a bit selective. Isn't it "God does not reveal himself in the world"? — Banno

That's what I originally wrote before editing the OP, but I thought it was redundant.

Where else would he reveal himself?

I'd also question the notion hat Witti had an "ethical Doctrine"; pretty much the opposite, such things being shown rather than said — Banno

Right, perhaps I didn't state that clearly, I meant Wittgenstein's doctrine about ethics, as appears in the Tractatus and in his “Lecture on Ethics”. -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)

but I too still reject things as false but they absorb into the wider ocean at the end of the day — Gregory

If you mean that contradictions can be true (dialetheism) or you claim that they are not actually contradictions, but seem that way due to our limited understanding, then you are making quite the extraordinary claim.

I'd just like to know how you (or Hegel) know this (that they will absorb into the wider ocean at the end of the day). -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)

I do read Hegel but a contradiction is not resolved by forcing it into place. — Gregory

Isn't that what you were trying to do here?:

I see transendence and immanence as different but the same, and God as us and not us. The physical and spiritual are two sides of a coin — Gregory

If the spaces between thoughts is wide enough, what appears as a contradiction will latter dissolve into something new and the difference between objective and subjective will radically change — Gregory

So, I'm not very knowledgeable about Hegel's philosophy, but I do know about his doctrine of thesis, antithesis and synthesis, which seems to be what you are setting forth here.

Following Hegel's idea, if we define the transcendental as something that cannot be apprehended by the senses or the physical sciences, then it cannot also occur in the world.

Is Hegel suggesting that if we apprehended the absolute whole, we would see that there is no impossibility or contradiction about a thing being both transcendental and immanent? How on earth does he know such a thing?

Not to mention that would imply that we have no reason to reject any claim as impossible, if we allow contradictions (even if they are only “apparent” ones). -

An argument for the non-existence of God based on Wittgenstein's theory about Ethics (+ criticism)That sounds a lot like Cusanus' doctrine that God is the unity of all contradictions. Though I suppose that you have rather Hegel in mind, right?

The problem with that view, which was pointed out by Aristotle, is that if we don't accept the Law of Contradiction (at least tentatively), discourse and knowledge are impossible. -

Is there a goal of life that is significantly better than the other goals of life?

I think there might be a standard or some other way to compare their strengths with each other......... A " Happy-o-meter" or something. — No One

Unfortunately, that seems impossible.

We know intuitively that some sensations are much better than others, but if we were asked: How much better is this sensation compared to that other sensation?

We wouldn't even know how to begin to answer that question, since we don't have the tools to measure such a thing (though perhaps in the future neuroscience could produce such a tool, I doubt it).And sometimes we don't even know if a sensation is superior to another. -

Is there a goal of life that is significantly better than the other goals of life?As for “what might be the greatest pleasure”, we should first ask: for whom? Some people would say food, others sex, others art, others spirituality, others wisdom, etc.

-

Is there a goal of life that is significantly better than the other goals of life?For me, it's not. For practical purposes I'd say: often “knowledge” can be quite painful.

But then again, being a sceptic in the theory I don't even know if I know anything or not.

Amalac

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum