Comments

-

David HumeAnd all of this is apples and oranges anyway because while there may be a limit to what inductive reasoning tells us about the actual world, deductive reasoning tells us nothing about the world. It tells us only about whether truth has been preserved from our premises, yet there is no suggestion (or requirement) that our premises be a truth about the world (e.g. all glurgs are gurps and all gurps are glomps, therefore all glurgs are glomps). So, you can talk about the limitations of inductive reasoning, but the limitations of deductive reasoning are more severe, as it tell us nothing at all other than whether we've correctly solved our Sudoku puzzle. — Hanover

Thank goodness for some commonsense.

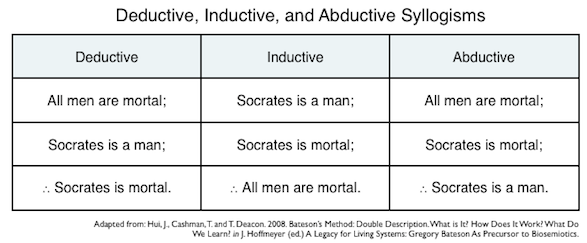

The interesting thing was that a valid deductive syllogism could be defined in terms of the three elements, the three steps, of a rule, a case, and a result. Some general "truth" that ranges over a class, some particular instance of that class, and then a consequence that could be predicated of that instance as a necessary fact.

And then the question arises of what happens when you play around with those three elements and consider what they say in a different order.

Induction was hazily understood as a converse of deduction - a step from the particular back to the general. But Peirce pursued the idea that induction itself was distinguishable into abduction and inductive confirmation. That was the way we actually seemed to reason about things in pragmatic fashion. And it was the way that science was turning into an explicit epistemology. Now you could see that this triadic story was itself already revealed in the formal tripartide structure of a deductive syllogism.

Of course the two varieties of induction were both "invalid". To go from the particular back to the general must involve a probabilistic leap of faith. A willingness to believe rather than to doubt.

But the whole problem with deduction is that it can't itself ever derive new information. It is just a system of syntax. It can only rearrange whatever semantics you put into it in a way that makes that move from the general to the particular.

So the "problem" with induction was really a problem with deduction. It was the rationalist dream that deduction could yield certain knowledge about everything. And in fact, by itself, it can yield no new knowledge at all. You needed induction to get the game started and to pragmatically justify the results.

The puzzle for me is that Banno keeps contradicting himself on these issues. One minute he is attacking the sceptics who just refuse to be pragmatic and commit to a belief that works. The next he is attacking the inductive basis of that pragmatism on the grounds the truth is "out there" beyond any such probability-based understanding.

Either he just hasn't sorted out a basic incoherence in his own epistemic metaphysics or he has something further to say which he just can't seem to bring himself to say. It's all very curious. -

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismWhat kind of content would you predict that a social species with a big natural interest in social dramas might find gripping? Stories of love, hurt, power and status? Stories that really engage their emotions?

-

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismWhat you cannot do is prove what is an innate instinct and what is socially constructed. Do you think "nurturing" is just an instinct or a tendency or preference that an individual may have towards something that originates by being provided the tools of personality/ego/introspection/environmental interaction that comes from a socially constructed mind? — schopenhauer1

I’ve already said there isn’t a sharp line as the two things are blended in development. The self is a mix of nature and nurture. It’s the same story as when we are talking about IQ or whatever.

The view being contested was your contention that instinct no longer played a role in humans after language came along.

So you are simply creating a straw man to attack now.

Any overriding metaphysics (like your peculiar brand of Peircian triadic semiotics) can be considered romantic. So, I don't think it does much to throw out this label. You are just creating a false dichotomy and then pitting one romantic vision (the interlocutor's) with your own. — schopenhauer1

Peirce would be a good metaphysics to oppose a bad metaphysics like Romanticism or reductionism. But ordinary science is quite good enough to argue against your claim concerning a lack of biological instinct in modern humans. -

David HumeHmm. Again it is baffling that you sound like you believe this is some kind of devastating criticism.

Abduction finds the assumptions from which conclusions can be drawn. Deduction finds the conclusions that can be drawn from those assumptions. Inductions then confirm that the conclusions support those assumptions in terms of the predicted facts.

Deduction might be semantics preserving in being syntactically closed, but it can’t generate new information. Whereas abductive inference and inductive inference are both probabilistic in spirit and can go beyond the evidence in ampliative fashion.

As I said, abduction does seem a work in progress. It is hard to boil down its holism into some more reductionist formalism.

But another way to get at it is as retroduction.

We can say the particular fact, A, is observed. And if the general fact, B, were true, then A would be so as a matter of course. Hence, there is reason to suspect that B is true.

So it runs deduction backwards from a conclusion to a likely assumption. And it should make you think a bit about why deduction is only secure in going from the general to the particular, while going from the particular to the general is inductive - that is, going beyond the evidence by a willingness to believe a high probability is good enough to be a workable certainty.

Isn’t that just what you always want when faced by these pesky doubters?

But I agree. Once you get into this business of abduction and the full pragmatist story of how we formulate knowledge, you start to see the much larger scope of the project.

Generality must be fleshed out with some kind of best fit principle. And this is the approach familiar in a philosophy of science understanding of the framing of natural laws. We want the generalisation that discards the most information. And that is in fact a balancing act - a best systems account (BSA) that opposes simplicity and strength.

So there you have a link to Ramsey, Lewis, and the like. Abduction can be bolstered by this same principle.

Likewise the principle of indifference is critical to finding a pragmatic grounding to the particular. There are always going to be an unlimited number of potential differences. But at some point - dictated by a purpose - any further differences will cease to make a difference. And we can see how this applies to the inductive confirmation.

So we need cut offs for the general, and cut offs for the particular. When those are supplied, a process of reasoned inquiry can become self-closing in the tales it tells.

Deduction is merely already closed - syntactically. It can’t discover new semantic content.

But deduction sandwiched between abduction and induction has the means to be open enough to learn and create content. Then achieve a satisfactory degree of self-closure. -

David HumeJust drop the word "absolute" and you can avoid vast quantities of philosophical guff. — Banno

So now you prefer the locution to be: "The answer would be that we can't have any kind of truth or certainty."?

Are you sure? Try again perhaps. -

David HumeGiving them a name does not alter their invalidity. — Banno

Calling them invalid does nothing except highlight that their truth claims hinge on matters of semantics rather than syntax.

It's so funny watching you trying to rescue your metaphysical preferences while pretending not to care about metaphysics. :P

Go on. Tell us about lunch again. -

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismI don't know, looked pretty much like you unwittingly agree, — schopenhauer1

That's what you get for trying to be precise I guess. Folk still don't take any notice. :)

The "I" is largely socially constructed, agreed then. — schopenhauer1

And largely biologically constructed as well. Don't now just ignore that.

However, what you cannot do is a sleight of hand where something that is "intrinsically rewarding" now counts as instinctual. — schopenhauer1

I said both the biology and the sociology can bring their intrinsic rewards. I was disputing your sub-premiss that having a family is intrinsically unrewarding on either account.

So you are now really mangling my reply.

Why have I enjoyed raising a family? I can see both social and biological reasons. It feels very instinctive to nurture. And also being a good dad is a socially approved activity.

You can say - in anti-natalist fashion - that both reasons are bogus. I am a fool for taking them at face value. But if we then take the debate to that level of general metaphysics, as we have before, then I still prefer my naturalistic account to your old-hat clash of Romantic idealism vs Enlightenment realism.

You are stuck in a discontented bind because of your incoherent metaphysics. But I don't find your problems to be my problems.

The decision to have less kids due to hard times, is a calculus based on the very linguistic-cultural brain that can do this sort of rationale. — schopenhauer1

You might also decide to have more kids as - if you are a subsistence farmer - more helping hands is a worthwhile capital investment.

It is situational. The point is that we are good at making choices given a situation. But what troubles us is when we have no particular influence over the situation itself.

So if there is "philosophy" to be done, it ought to be aimed at creating better situations if there is indeed something not to like about the ones we are in.

Of course, your pessimism is predicated on the impossibility of situations ever being good. And stubbornness will turn that into a self-fulfilling prophecy very quick.

This is a live issue. My daughters are in their 20s. I see many in their circle of friends going into self-destructing spirals because they turn in the wrong direction when faced with any challenge.

Now certainly modern society can be blamed for the kind of challenges that the young face. But also, it is obvious that many of them have faced so little actual challenge in their growing up that absolutely everything becomes a challenge as soon as they want to start standing on their own feet.

So it is a complex story. Yet also very simple. Bad metaphysics can really screw your life up. :)

What I am trying to do is show that raising a child is a preference like any other preference- it just happens to be a popular one because of cultural pressures. — schopenhauer1

Yes. You need it to be axiomatic that it has to be an external pressure rather than an intrinsic desire. Yet with a straight face you then also say you are a social constructionist and a naturalist. But if we are socially constructed as selves, then that "pressure" is simply our true being finding its expression. It comes from the self - as much as there is a self for it to come from.

The confusion kicks in because we are then both biological selves and social selves. The communal self we share at pretty basic level. The phenomenological self we share at an even deeper biological level, but also we don't really share at all beyond our capacities for empathy and mirroring.

So there is complexity here again. But don't let it confuse the argument. If you are focused now on the socially constructed self, then you yourself removed the very grounds to complain about any individual preferences being socially constructed.

There is a basic logical flaw in your argument. It shows that you are operating from the incoherent and dualistic paradigm which is Romantic idealism vs Enlightenment realism.

Beyond the obvious physical pleasure involved in sex, the preference for actually procreating is simply in the imagination, hopes, preferences, of the individual just like any other goal that is imagined, hoped for, preferred, etc. — schopenhauer1

No. You just said that the psychology of that individual is largely a social construction. Indeed, you have been arguing that Homo sapiens represents a complete rupture with nature in this regard. Instinct was set aside and we became totally cultural creatures.

Anyway, having said the pressures were social and external, now you are switching to talk of them being internal and individual. The next step in your faulty argument is to then say that is why these individual preferences are falsehoods imposed on people unwillingly. As if they had some other more legitimate self - an inalienable soul. Which you will then say they can't have - as Newtonian physics and Darwinian evolution proved God is dead and life can have no purpose or value.

You have trapped yourself in a bind - even if not one of your own making, but one that simply recapitulates some bad socially-constructed metaphysics.

So how will you react to that realisation? Will you again go through each point and find that I unwittingly agree with you despite whatever I might have actually said? -

David HumeIt seems odd, then, to back up one's belief that the chooks will lay eggs tomorrow with a vast, profound theory of pragmatism. — Banno

What's odd is that you want to waste all your time on a philosophy site ranting against critical thinking.

But I'm guessing you suddenly have a lot of time to waste for some reason. -

David Hume...the first question, which is "how can we hope to have certain knowledge?", will remain unanswered. I think the first question makes no sense at all. — Magnus Anderson

The answer would be that we can't have any kind of absolute truth or certainty. So it is a question that was answered. That clears the field to get on with a pragmatic approach to truth and certainty.

Well, there is still then tautological, deductive or Platonic truth. Folk will want to say deductive logic is at least truth-preserving when the syntax is valid. It maps one state of affairs to another without loss of semantics. We could have a debate about that.

And then there is the allied thing of mathematical truths - the things we say about abstract objects like triangles. We can know those things for sure, in a necessary fashion. Again, we could have a debate about that too.

So in a general way, the absolutism is long dead. Pragmatism rules. But at the fringes, people still want to maintain some kind of unquestionable certainty.

So abduction, if I understand you correctly, is a pattern of no-pattern of thinking. You say that it is the least formalisable pattern of thinking which suggests to me that it lacks pattern to a considerable degree. Or it could be that the pattern is complex and thus difficult to understand and formalise? Which one of the two is the case? I am inclined to think the former but I like to keep my options open. — Magnus Anderson

Not really. I was emphasising how we know it is an important part of successful thinking, and yet we are not sure if we can formalise it. We would certainly like to if we can. One of Peirce's many foundational contributions to logic was to bring the issue out into the clear light of day. I argued that he was less successful at given a proper answer.

My own thinking is informed by modern science and its efforts to build pattern recognising machines, as well as the efforts to understand the same in human brains.

Why do Fourier transforms work so well in signal processing, for example? Why do generative neural networks seem a powerful approach? We do have some mathematical models to consider now.

So if abduction is a process of thinking that has very little pattern within itself, this means that abduction is mostly a random process. It's basically random guessing. — Magnus Anderson

Well if that were so, we would hardly ever arrive at a useful hypothesis. It would take us a lifetime to answer a single question in any ordinary IQ test. It is just a simple fact that we can leap towards the explanations which erase the most information and leave us with the core principle we need to follow.

Our brains do it all the time. The question becomes, how? It certainly ain't a serial search process. It certainly doesn't rely on random exploration. There is something gestalt and holistic in how we can feel the edge of an answer and then watch it flesh itself out into a fully fledged aha!

So the brain is doing something in information processing terms - unless you believe that all such mental activity is connected with divine powers.

If you see a disembodied head lying on the floor you are not going to assume "someone clapped his heads and this head popped out of nowhere" you are going to assume something like "someone's head has been cut off". That betrays order. Not necessarily in reality but in thought. — Magnus Anderson

Yep. So inference to the best explanation.

And what should be noted is that we can imagine a gazillion reasons for there being a disembodied head lying on the floor. Maybe a dinosaur bit it off. Maybe that dinosaur was a pterodactyl or a t-rex. The possibilities are endless.

But no. If we are actually any good at this business of reasoning, we will discard a gazillion possibilities pretty much instantly. We will come up with some maximally plausible guess. We will use all the information to hand and assign some Bayesian process of evaluation that leaves some central body of possibility as whatever is the hypothesis that can't be so easily eliminated.

Even Sherlock Holmes knew that. He was the master of abductive logic after all - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sherlock_Holmes#Holmesian_deduction

Abduction has the following form:

1. Event B occurs.

2. When event A occurs event B follows.

3. Therefore, event A occured before B. — Magnus Anderson

Well yes, Peirce did notice that the same terms employed by the classical versions of deductive and inductive arguments could be used to generate a third kind of argument.

So an abductive argument was already contained within the standard formalism. It followed on directly from the truth of those other two. It was there implicit and waiting to be recognised.

That should be a pretty striking fact I would have thought.

If you aren't interested in either induction or deduction, then you won't care about abduction either. But if you do care about those two things, then you have to care about the fact that the same elements just automatically then have a third combination.

-

David HumeThermodynamics is part of physics, not metaphysics. — Banno

Really? Is that the best you can do? -

Against All Nihilism and AntinatalismSo, despite your protestations to the contrary, your very evidence indicates you believe cultural learning is largely the vehicle for which humans procreate and follow a preference to raise children. — schopenhauer1

Err, no.

I already agreed that sex is the "basic" instinct via the general tendency to prefer physical pleasure, but that is not the same as literally the conceptual idea of "I prefer to raise a child" which involves much higher cognitive understanding and cultural ques than mere physical pleasure. — schopenhauer1

Well when you shift the goalposts that way, then claiming that there is an "I" that has an innate preference is of course what would be countered by a social constructionist point of view on the subject.

You are now framing it as a personal choice. Which in turn demands a Cartesian model of a choosing self.

The argument was about this "self" being unwillingly forced to procreate due to evolved instinct vs being unwilling forced to procreate by some social necessity. And your emphasis either way is on the unwilling. Yet either way, it might be a willing inclination in being an intrinsically rewarding or pleasurable action - the rewards of having sex and then raising a family being something that both biology and sociology would have reason to celebrate.

Based on your own response, the score is:

Cultural learning- 4

Instinct- 1 — schopenhauer1

You mean based on your own spurious marking system.

If you want a score, clearly you are flat wrong in suggesting that Homo sapiens abruptly left behind biological instinct when it became a linguistic species.

And you would be right to the extent that you might then make some more nuanced case for the cultural malleability of our procreational habits.

I mean everyone knows that we respond to social economics. You either have a lot of kids, or try to avoid having kids, depending on the economic equation as you see it.

And even my pet fish - dwarf cichlids - can make that kind of decision. They lay eggs and then either eat them or protect them, depending on some instinctive judgement about the situation in their tank.

So really, the same evolutionary logic is at work, just at a higher level of sophistication.

Anti-natalism depends for its grounding on some kind of anti-naturalistic metaphysics. It arises from being disappointed by the Romantic promise that being alive has transcendent meaning, and then Enlightenment physics saying no, life is transcendently meaningless.

Well as you know, I just reject that metaphysical framing. I take the natural philosophy route on all questions. And that accounts for the issues here with ease. -

David Humeif any of these disbarred tomorrow from following on form today, we would reject them. — Banno

How exactly could you reject them without determining which of them was responsible for some failure of prediction?

You could plan your future with Tarot cards, bedtime prayer, or gut intuition. Those have been pretty everyday habits in the past. Was there some reason they might have fallen out of fashion in the planning of your own life? Or do you still put your avocadoes in a magic box to keep them fresh, or instead a thermodynamic device called a fridge?

What metaphysics does your actual daily routine depend upon? Of course, the fridge might as well be a magic box to you. But the good folk who designed and built it might have needed some more rigorous reality model, don't you think? -

David HumeSo I think Hume had it pretty well right, in describing our acceptance of continuity as a habit. It's not something that requires justification. It's not as if, were we unable to find such a justification, we wold cease to plan our mealtimes. — Banno

Again, it is wonderful that you accept a pragmatic account of truth and rationality. But you are still confusing philosophy with your personal satisfactions.

Animals don't need to have an epistemic theory either. A reliance on an unquestioned habit of inductive generalisation is good enough for their everyday purposes as well.

But I'm not sure why you think that the everyday routine of your eating habits is all there is to say about epistemology. I guess you just enjoy taking an anti-metaphysics stance to its caricatured limit. But in the end, who cares when there is interesting metaphysics to be discussed.

Just don't distract us too much with all your noisy chomping. -

David HumeSo before we invented entropy we could not plan our lunch.

Your account is just too complex. — Banno

Well, maybe some of us have larger epistemic concerns than the world that encompasses our breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Your account is just so shallow. ;) -

David HumeBut the future is not like the past.

Yesterday I had a full bottle of red. Now it is only half full. — Banno

Erm, the story is that the future is like the past in that its total entropy has increased by much the same amount yet again.

The basic constraints in play are the physics of thermodynamics. And Hume/Newton were talking about the physics in play. It was just that that physics was the reversible story of inertial mechanics, not the irreversible story of the Cosmos as a dissipative structure.

So the surprise - the disproof of an inductive metaphysics - would be if your pissed-away bottle of red magically reconstituted again itself each night, like a Magic Pudding.

So yesterday, the slope was downhill. And tomorrow, the slope will still be downhill. That is the inductive claim here. -

David HumeI have yet to see the relevance of introducing the third type of reasoning that is abductive (or retroductive) reasoning. — Magnus Anderson

The relevance is that it introduces a third and missing step in reasoning as a holistic process. And it is interesting in that so far it is the least formalisable. It would be really important if we could add a formal model - a potential algorithmic approach - to our arsenal of intellectual tools.

The unarguable point is that humans are remarkably good at guessing right answers if we took a strictly random search approach to creative insight.

How do we form our intuitions in the first place? It can't just be that we try every possible key to unlock the door. Peirce made mathematical arguments about why a random search couldn't be executed in the lifetime of the cosmos. And the same arguments are made today about NP hard solutions.

Folk like Roger Penrose have really gone to town on the issue, saying it proves to them that conciousness must be a non-computational quantum process. So it wasn't just Peirce. This is an issue that is central to a lot of metaphysical positions, as well as being of great practical interest in human psychology and artificial intelligence.

Peirce actually was leaning towards a pretty mystical answer on the "how" of abduction. He talked of Galileo's il lume naturale. He wanted to use the existence of inspired guessing as a proof of the divine. And so - in that regard - I am hardly peddling the Peircean line. Although that then depends on how you interpret what Peirce actually wrote.

Anyway, my own naturalistic view is that human minds - being evolved to understand worlds - are good at unbreaking broken symmetries. We can inductively generalise and so leap to an understanding of what the unbroken generality must have looked like before it became broken in the particular way it presents itself to us.

This is a Gestalt or Holistic deal. The whole brain is set up to see figure in terms of ground. The figure breaks the symmetry of a ground. And we can then turn our attention to the nature of the ground that had that general potential to be broken.

So the search isn't a random stumble that would take forever. Awareness is already developed in a fashion that represents a symmetry-breaking. It is already broken into figure and ground. Reversing that is just a case of relaxing the mind in a certain fashion to allow the backdrop to be seen in that light. It is a short leap - like seeing the negative space in a reversible Gestalt image of vase and two faces - rather than a blind computational search through every alternative.

I guess it all depends what you think is a central question of epistemology. Is it how can we hope to have certain knowledge? Or is it how is it that we can reason in optimal fashion?

The two were connected for a while - particularly where Newtonian science finally cashed out the deterministic simplicities of Ancient Greek atomism. Determinism, deduction and computation all go together as neat metaphysical package that appears to promise absolute certainty - something quite miraculous to humans more accustomed to thinking of the world as an arbitrary and uncertain place.

But we are beyond that now. The other side of the story is again more interesting. -

Against All Nihilism and Antinatalismook at a baby human versus that of many other mammals. The baby human is the most defenseless. Why? Very few innate behaviors. Also, the epigenetics and the learned behaviors of other animals also have an instinctual component that is not driven by the much more generalized learning process that humans posses via linguistic/conceptual brains. — schopenhauer1

Since you asked, Schop, I agree with Pseudonym that you seem to be trying to draw too sharp a line here. It doesn't make sense to argue that Homo sapiens abandoned neurobiological instinct for socially-constructed desires. Sure, socially-constructed desires radically change things for humans. Yet the underlying biology continuity still exists and we can argue that linguistic culture largely serves to amplify that evolved instinctual basis rather than to somehow completely replace it.

Yes, it is possible that humans evolved to be less instinctual so as to be more open to cultural shaping. But I don't think there is much actual evidence of that being the case.

Humans are born more helpless - their brains a mass of still unwired connections - because we happened to become bipeds with narrow birth canals trying to give birth to babies with large skulls. The big brains were being evolved for sociality and a tool-using culture. So babies had to be squeezed out helpless and half developed, completing their neuro-development outside the womb - a risky and unique evolutionary step. But also then one with an exaptive advantage. In being half-formed, this then paved the way for the very possibility of complex symbolic speech as a communal activity structuring young minds from the get-go. It made it possible for culture to get its hooks in very early on.

Of course this evolutionary account is disputable. But it seems the best causal view to me. And while it says that there was undoubtedly some evolutionary tinkering with the instinctual basis of human cognition - we know babies have added instincts for gaze-following and turn-taking, stuff that is pre-adaptive for language learning and enculturation - you would have to be arguing for a more basic erasure of instincts that are pretty fundamental for the obvious evolutionary reasons that Pseudonym outlined.

It is natural that animals would have an innate desire to procreate - have sex. And it is natural that animals would have innate behaviours that are particular to whatever parental nurturing style is their ecological recipe for species success.

These in turn might be highly varied. There are many possible procreative strategies - as you know from discussions of r vs K selection.

http://www.bio.miami.edu/tom/courses/bil160/bil160goods/16_rKselection.html

However we can make reasonable guesses about what the human instinctual basis was, and remains. Certainly a desire to have sex and an instinct for nurturing are pretty basic and hormonal. Which is enough to keep the show on the road so far as nature is concerned.

Now arguing in the other direction, I would agree that this hardwired biology is not of the "overpowering" kind popularly imagined. Culture probably does have a big say. As society becomes a level of organismic concern of its own, it can start to form views about what should be the case concerning procreation. The drivers might become economic, religious and political - these terms being a way of recognising that society expresses its being as economic, religious and political strategies.

And likewise, society might wind up turning individual humans into largely economic, religious or political creatures. We might really become incentivised to over-ride our biological urges as a result of the direction that cultural evolution is taking. This may get expressed in terms of the full variety of r vs K strategies. We might get the range of behaviour from Mormons or other cultures of "strength through big families" vs the economic individualism which turns supporting a family into a financial and personal drag (with the individual now becoming, in effect, a permanent child themselves - never wanting to grow up and so creating a new dilemma for the perpetuation of that society, as is big news in Japan).

So, in my view, it is too simplistic to draw a sharp line between biological instinct and linguistic culture in humans - especially when it comes to any hardline anti-natal agenda. Although there is certainly this added level of evolutionary complexity in play with Homo sapiens.

We are at an interesting time for humans. Society has shifted from an agricultural basis to an industrial one, and now believes it is entering an information age that really cuts itself off from its biological roots. So culture is churning out individuals with psychological structures that express that current stage in its development.

Can that mindset flourish and last? Is it realistic or out of touch? Can a society predicated on life-long infantilism survive?

It might, if we can all afford robot slaves and crack the fusion free energy problem, etc. Anything remains possible - that is, if you don't pay any attention to the underlying economics of biological existence itself. The bottom is surely about to fall out of that dream - that we aren't simply a species gorging on a short-lived windfall of fossil fuels. But that's another thread. -

David HumeYou have to rely on the assumption that the future will be like the past in order for past evidence to be relevant to the future. Which is assuming the conclusion. I don't object to you doing it, I just object to your claim that is is reasoned. — unenlightened

The reasoning might not be purely deductive, but it is scientific reasoning that thus includes a deductive element.

So a full account of the reasoning would go that we start with an abductive step - a guess at a causal mechanism. Then we deduce the observable consequences. Then we tally the inductive confirmation.

As I argued earlier, a belief in induction is justified by a guess at a mechanism - history builds constraints on free possibility. Then from that, we can deduce the observable consequence - the past can be used to predict the future in this fashion. We will see this causal mechanism at work. And then observation - of the success of this inductive approach - will be inductively confirmed (or not).

The Hume/Newton thing arises out of a particular metaphysics - a belief that the world might be deterministic, atomistic and mechanical. But rather paradoxically, that nominalism created some serious realist type problems. It couldn't account for the existence of backdrop dimensions, such as space and time. It couldn't account for how physical events were ruled over by natural laws. It couldn't account for gravity's action at a distance.

The background metaphysics that Hume relied on to motivate an argument was so patently full of nominalist holes that it never was a complete story. Yes, it did speak to a deductive consequence of its axiomatic hypotheses - all the guesses about determinism, atomism, etc. And that part of the belief system could be inductively confirmed in its own terms. But then it also relied deductively on a set of unobservables - like the laws, and space-time, and action at a distance. These "must" exist according to the metaphysical set-up, but they could never be directly measured or shown. So they could not be inductively reasonable as such.

So Hume was making points that seemed appropriate in a particular metaphysical context. They were "reasonable" in his day. But if we are talking about a modern scientific view of reasoning, then introducing the third thing of abduction, or an axiomatic leap of the imagination, makes a big difference. It says knowledge works quite differently from how the traditional conflation of deductive logic and rationality might want to represent it.

The sharp line folk tried to draw between the rational and the empirical was too strong. All reasoning relies on a mix of both. And indeed, the mixture is triadic.

You have forms of induction book-ending the process. Abduction is the generalisation step, the inference to the best explanation. It begins as vague or hazy intuition and snaps into crisply expressed hypothesis.

After that, deduction can kick in. It has something to work on and can do its syntactic, rule-bound, thing. But while the consequences of deductive argument carry the stamp of certitude (valid is valid), it is still a case of garbage in/garbage out. The hypothesis might be wrong, or more likely just part of the story. So nothing is reasonable until it is measured against the world it pretends to model. Induction from the empirically particular back to the abductively general has to close the loop, confirming the initial guess is right (or right enough for all practical purposes).

So "reasonable" should mean reasonable in that full scientific method sense. And induction itself seems reasonable in that light. We can guess at a mechanism - the accumulation of constraints. We can deduce the observable consequences. We can measure the degree to which nature conforms to our model.

And as I say, we then encounter the ways that nature doesn't in fact conform - as in the frequency with which abrupt or catastrophic changes do occur in the world. So at that point, we need to go around the loop again. We realise that we were presuming a linear world. We need to develop a larger model that relaxes that constraint. That leads us towards non-linear models - non-linear models being more generic than linear ones. -

Thoughts on EpistemologyWhether a doubt feels vaguely intuited or crisply expressed is a separate issue. And one that makes no essential difference except that a doubt has to be made concretely counterfactual to achieve the status of being part of a rational argument.

-

A Way to Solve the Hard Problem of ConsciousnessHas the Cartesian dualism inhering in the earlier generation of cognitivism, with its sharp dichotomizing of affect and cognition, been overcome by what you have called the general physicalist monism of the newer approaches(and some not so new ones)? — Joshs

Fair enough. I am biased because I particularly sought out those who I felt took a properly integrated view of the issue.

So yes, the Platonic tripartide model of humans - reason as the charioteer trying to control a chariot pulled by the two horses of the higher passions and the baser instincts - still has a lot of cultural pull. And a computational turn in psychology really did foster a brain in a vat view.

For me what is crucially at stake is the ethical-psychotherapeutic possibilities opened up by a way of thinking. — Joshs

Heh. So now this is yet another direction. I'm not sure what you have in mind exactly.

It seems to me that today one set of cognitivists gather on the conservative, that is , Nietzschean-Darwinian, side of a philosophical divide, while a much smaller group(Shaun Gallagher, Varela, Jan Slaby, Matthew Ratcliffe) attempts to incorporate into their thinking phenomenologists like Husserl, Merleau-Pony and Heidegger , and poststructuralists like Foucault and Lyotard. — Joshs

Well, I wouldn't be on the side of the PoMo johnny-come-latelies. Another personal bias. I am with the structuralists rather than the post-structuralists. :)

But also my views are based rather directly on the science. So I am dealing with concrete neurobiological models and empirical evidence. SX is probably more into the philosophical politics here.

I'm sure you're aware that this latter group of philosophers is responsible for the ongoing assault on the presuppositions of physicalist science.

We are accustomed to dealing with this from humanities and cultural studies departments, but a gentler version of it is now being put forth by those calling themselves cognitive scientists. — Joshs

So you are saying that the PoMos are attacking the physicalists and the Darwinian conservatives are attacking the PoMos?

It seems what you would be saying, but it reads a little hazy.

Would you agree that the philosophical understanding of concepts like quality, quantity and essence have undergone continual shift over the past centuries, and those changes in understanding make their way subtly into the empirical descriptions of scientists?

If so , then I would expect that the notion of quality as a 'general theoretical essence', which is about as Cartesian a definition as I can imagine, has room for updating. — Joshs

Again, I'm unclear about your point.

But what I'm thinking is that science - to be quantitative - has to in the end just operationalise the metaphysical qualities it seeks to explain. And this is not necessarily a bad thing. It seems an honest thing.

So science invents these terms like energy or entropy that are essentially pretty meaningless. They sound like science is speaking of some material substance, but really the terms just become place-holders for something that is a constant factor or a conserved quantity. It seems like there is some stuff. And thinking that way allows for a system of measurement which speaks about quantitive variations in that stuff - differences in its location, form, amount, etc. Yet the scientists don't really believe the stuff has the substantial being that giving it a solid-sounding name implies.

This has become really obvious now with the information theoretic turn in physics. Now science just shrugs its shoulders and say we can count primal bits. We can throw away all the materialist presumptions and treat the purest quantification - a 0 and a 1 - as the quality, the conserved stuff, that we know how to measure.

To me, that's pretty sophisticated. Especially in contrast to the qualia talk that kind of does the exact opposite for philosophy of mind. It doubles down on materialism by adding a mental stuff to the physical stuff.

So I see the information theoretic turn as a paradigm shift that can get science out of a material monism without then falling into a Cartesian dualism.

But I doubt that was the angle you had in mind.

So again, is there a question here? Perhaps the PoMo take on a phenomenological alternative to mainstream neuroscience's Darwinian naturalism concerning embodied cognition offers important psychotherapeutic results. That might connect the dots. However if that is the line of thought, I'd need more details to have a view. -

Thoughts on EpistemologyWhenever something doesn't seem quite right, there is cause for doubt. — Metaphysician Undercover

But how could you know something wasn't quite right unless you were making a prediction that it would be otherwise in some sense?

So yes, the prediction might not be a vivid and specific expectation - an attention driven prediction. But it could still be a prediction in the sense that you have some habitual expectation about things, and then that more general expectancy is the background against which surprises can pop out and catch your attention. -

Thoughts on EpistemologyNo amount of clarification of terms will overcome that fundamental untranslatability of language. — Joshs

But when you say something that actually reaches past a conventional or habitual level of understanding, isn't that the feature rather than the bug? Isn't that how philosophy or understanding generally manages to stay creatively open and progress?

So every sentence of any interest remains open to fresh interpretation - even to oneself. We can twist it and turn it in the light to see new possibilities of what might be meant. The meaning is not fixed but already open to another point of view.

This is one of the things that flips a theory of truth on its head. Language is not a system of frozen meanings, petrified semantic commitments. At the creatively open edge of reason, even the same sentence can be understood many slightly different ways by its own speaker. And that is a good thing. It is how language can both stretch itself elastically while also aiming at some tightest possible fit.

I see that as the dichotomistic tendency of Grayling's OC1 vs OC2 which Sam cites here. Plasticity vs stability. Novelty vs habit. A basic relational freedom combined with the possible discovery that there is some eventual metaphysical-strength limit.

All this talk about belief vs doubt. Sam was saying something that didn't make much sense to me about neural states. But the neurobiological story of the brain is how it is organised by the dichotomy of the habitual vs the novel.

If we want proof that knowledge is built on a "background" of unquestioning belief, then we can read that story into the way the brain is founded on the accumulation of useful and embodied habits. And then in complementary fashion, the brain is also designed to "doubt" - apply its attentional resources - whenever this general backdrop of belief fails to predict the world in suitable fashion.

So a naturalistic basis is right there to be seen. However its logic is dialectical. Which is where things start to go all uncomfortably Hegelian for some. :) -

Thoughts on Epistemologyyouve taken what should be a common curtesy towards Sam as the instigator of this thread and turned it into an excuse for your not starting a thread Of your own. — Banno

Dry up Banno. I made posts that addressed his points about neural states and attempts to find a grounding in something inarguable because it is "natural". If we are now discussing red herrings like whether Paris is the capital of France, it is because of your efforts to deflect from the pragmatism towards which Wittgenstein was moving.

There is actually an amusing contrast here. Peirce started off as a quietist and then became keen on a metaphysical-strength epistemology. So how that pans out could be instructive for someone actually wanting a foundational story.

If you are not interested, fine. Butt out. -

Thoughts on EpistemologyYep. Whenever it comes down to it, you don't actually have an argument. It was simply a posture.

-

Thoughts on EpistemologyThat's the trouble with pragmatism. It does not address questions of truth. It pretends they are all questions of justification. — Banno

That's true.

But can you explain to me what the difference actually is as far as you are concerned.

Of course, pragmatism doesn't actually pretend its all just justified belief. Just like it doesn't deny the world exists in some fashion that is separate from our desires and conceptions. So it certainly addresses the question of truth head on and gives its pragmatic answer. But again, the stage is yours. Tell us what the critical difference is here, using the example supplied.

To remind, "God created the earth and mankind, the Big Bang never happened" is true IFF God created the earth and mankind, the Big Bang never happened.

So who speaks the truth here, and in what way is that so? -

Thoughts on Epistemology"P" is true IFF P. — Banno

So let's take a more useful example to flush out what you could possibly mean by epistemic justification.

"God created the earth and mankind, the Big Bang never happened" is true IFF God created the earth and mankind, the Big Bang never happened.

Fine. In the most question-begging way conceivable, we have set out a truth condition.

But now how would you go about cashing that proposition out? If you claim to be interested in epistemology, then start doing some.

We have two convinced schools of thought - the creationists and the cosmologists. How does "Paris is the capital of France" as your prototypical example of commonsensical truth apply in sorting out how doubt and belief ought now to proceed here.

If you were actually saying anything helpful in pushing that example, its usefulness will be made clear in your very next post. -

Thoughts on EpistemologyThat's as close as can be got, and I have said it to the point of tedium. — Banno

And to the point of tedium, you won't discuss the informal acts of measurement that are needed to show such truth in practice. So same old same old. You leave out the "self" that is needed to give propositions any grounding purpose and any natural limits to their concerns about errors, exceptions or doubts.

And of course, that extra stuff is central to making sense of such different classes of proposition as Paris is the capital of France, and here is one hand, here is the other. -

Mental States and DeterminismSome Brief Arguments for Dualism — Wayfarer

Rather that's a brief argument for semiotics and the epistemic cut.

Yes, it shows that there is a separation of our "minds" from "the world". The interpretation of marks is separate from the physics of the marks. And in turn, that informational separation is how interpretance can arise to regulate the actual physics of the world with some purpose in mind.

But actual dualism is avoided by there being that living connection - the feedback loop which connects the two sides of the modelling relation. The habits of interpretance can only survive to the degree they do useful material work.

So the mind is actually free or transcendent. It is embodied and rooted in an ultimately physicalist purpose. -

Thoughts on EpistemologyIndeed, as you were so forthcoming when asked if it is true that Paris is the capital of France. — Banno

That's a little lame when you wouldn't give a definition of what "truth" might be taken to mean in your view.

I agreed it might be tautologically true according to some social convention. And I pointed out how inadequate such a definition of "true" might be in any sensible debate about realism - as might hinge on Prof Moore and his flapping hands.

But as usual, when faced with an actual argument, you went radio silent for a while. And now re-emerge clinging onto this as some unanswered winning remark you might have made.

You can always go back and address my actual replies. But I know you won't. It's all impression management as usual. -

Thoughts on EpistemologyNotions of absolute truth were laid to rest at the start of last century, with Moore and Russell's criticism of Absolute Idealism. — Banno

Hah. Well there is certainly still something in Hegelianism. But it took Peirce to make the case that there is no direct correspondence between the reasoning subject and the objective world. The mediation of the relation by signs pretty much ensures that there isn't - as the comprehending self and its comprehended world arise separately from the world in itself.

So what you are expressing here is some personal prejudice about what have been the twists and turns in the development of epistemology. Moore and Russell hardly ended anything. They were already blundering into logical atomism.

The world is too complex for one Grand Scheme to provide us with The Truth. — Banno

Oh dear. Again that may be your impression, but after checking out the great variety of epistemologies on offer, I am repeatedly surprised by what a robust scheme Peirce arrived at.

So you have your view. I have mine. The difference is mostly that I am prepared to supply the arguments and evidence for mine. You instead have adopted the easy position of the arch-sceptic. You can just keep saying "I doubt that very much".

You even seem proud that you won't even read anything about Peirce when it is offered. It's a funny attitude to encounter. But variety is what I enjoy.

Pragmatism says nothing of the truth of love, beauty, courage, respect. It is a philosophical sideline. — Banno

Hmm. But pragmatism done properly speaks directly to the values of the "self" that is doing the philosophising. I keep point that out to you. It puts the other side of things - the self that hopes to discover itself in its world - in the limelight.

Of course, this is a fundamentally anti-Romantic and anti-Transcendental enterprised. A lot of folk - you too apparently - don't like that mystical side of life being called into question and treated as a scientific inquiry.

Yes. I can see how it might seem to threaten Philosophy. Science has taken over metaphysics pretty much entirely, and now it is back for the rest. :)

But to me, that is what progress looks like. And I'm always willing to make the argument in full. I don't need to hide behind ambiguous non sequiturs and one liners. -

Thoughts on EpistemologyPerhaps talk of absolute truth lead philosophers astray, so that they threw out good old plain ordinary truth along with absolute truth. — Banno

But that's not really the issue, is it. Yes, of course, it is impressive that we seem to find it pretty easy to deal with everyday "truth". Agreeing on the facts is simply about mastering the right social habits.

So where philosophy begins is when we want to move on to an epistemic theory that itself is "true", or at offers an analysis of the best way to go about things. This is basic to moving away from the everyday socially-constructed forms of knowledge and establishing an epistemic method that can be extended way beyond into the realms of the metaphysical even.

The search for that ideal epistemic method is hard and ongoing. But we can see that it has largely cashed out as pragmatism and the scientific method of reasoning. And philosophy as a training aims to foster the critical thinking skills which are involved in applying that epistemology.

So you can continue with your anti-metaphysical griping. It counts for nothing. Metaphysics is alive and well. In scientific circles anyway. :)

The correct employment of doubts (and beliefs) is an issue. But just as obvious is that most folk have no trouble distinguishing between the everyday socially constructed truths (like Paris being the name given to a city that has also been designated a nation's capital) from the philosophical issues surrounding epistemology itself.

In conflating the everyday with the deeper story, you not only show a failure in critical thinking, you also wind up excluding what is actually fun and interesting about metaphysical level inquiry. And that makes for a dull life, wouldn't you say? -

Thoughts on EpistemologyOne might be things we are cause to take as indubitable - Sam, from the OP.

Another might be constitutive rules, which might be doubted outside the game they help constitute.

A third might be propositions that are shown, such as "here is a hand". — Banno

1) The first is too strong. Even an axiomatic or grounding supposition needs to be doubtable to be believable. It has to be framed in a way that has an explicit contradictory - a counterfactual axiom - to even have any explanatory bite and not merely get classed with the set of propositions that are “not even wrong”.

So of course we choose axioms on the grounds of being the least doubtable. That is how they can be the most believable. But the fact that the whole business is founded in this counterfactual game means that the necessity is more about the necessity of just making some abductive leap. We can always circle back to have another go at the axiomatic basis if the results of the axiomatic system don't seem to be working out so well ... on pragmatic or empirical grounds.

2) The second is right in emphasising the need to just make some rule to get a game of inquiry going. Even a bad guess is a good guess so long as it is a definite guess - one that is crisply counterfactual in its framing.

But what we need to avoid is the suggestion that the game is arbitrary. The game is going to be judged in terms of the purpose it accomplishes. So there is that global constraint, the empirically-grounded one, that feeds back to say something about the quality of the grounding axiomatic choices.

And also, more needs to be said about the epistemology of abduction. Peirce already made the mathematical argument that the history of the universe is not long enough for humans to have made even a few right basic guesses at random. So we need an explanation for why our guesses tend to be rather good. And the reason is a non-linearity, as illustrated by the exponential ability to discard alternatives in the classic 20 questions game. If we can cut the total number of possibilities in half at every step, not just knock them off one by one, then it is much less of a surprise that we can employ a dialectical logic to generate our metaphysical axioms.

We arrive at constitutive rules via dichotomies for a good reason. Non-linear search beats linear search by a country mile^2. ;)

3) The third is the baffling one. It seems like an attempt to be empirical. It claims - in pointing to something particular - to demonstrate the existence of some grounding or backdrop context.

But while that background of belief exists, it would be better just to point to it directly. Everyone of course can see by your actions that you presume a certain dichotomy of self and world to be basic. But better to say that directly - put it verbally on the table for forensic examination - rather than try to get away with some ostensive demonstration.

It feels always too much like an attempt to evade real debate than to answer the sceptic. To grunt and point ain't ever as good as presenting a proper epistemic theory.

So yes. There must be some general ground of belief that then makes all further doubts crisply local and particular. That is standard pragmatism, and standard psychology. Without an established set of habits, we could never do anything that actually counted as creatively novel.

But flapping your hands about and appealing to the strength of some established communal belief shared by an audience just seems a bad faith attempt to dodge the serious epistemic questions at stake. -

David HumeApo must be having a bad day. It usually take three or four posts to goad him into an ad hom. — Banno

Bad day? Every laugh at your expense must surely be an entry in the credit column of the great ledger of life. And now you admit that your aim is to goad. Checkmate, mate.

So, the necessary Banalities having been completed, let’s get back to you explaining to me how empirical correspondence operates in the absence of conceptual coherence.

You prefer the one, and hope to avoid mentioning the other. But sadly, even induction relies on a coherent metaphysics back in the real world of pragmatic knowledge.

And I just demonstrated that fact in mentioning the need to incorporate catastrophe theory into any full view of the probabilistic basis of reasonable inference. These days (well, for these past 40 years at least), you would need a positive reason to believe your phenomena actually inhabit a stable linear realm of constraints. You would need to know there was no parameter slowly creeping into critical territory.

So how do you work that discovery into your own personal worldview I wonder? (Well not really, as it’s obvious.) -

A Way to Solve the Hard Problem of ConsciousnessAs far as the history of psychological theory, where have you seen accounts integrating the affective and the cognitive before 10 years ago, outside of a few fringe writers? — Joshs

Well my view is shaped by having being deeply concerned with the research into the question 30 years ago. So yes, there was a cogsci representationalism that was the mainstream at the time. And I was interested in the counter history of the more embodied and affective approaches.

There were plenty around, I found. For instance the Soviet work on orienting responses that followed on from Pavlovian conditioning was very influential on me. But also, it would be fair to characterise it as fringe through the 1980s. And personally I was a little annoyed when a second rate hack like Damasio came along at the right moment to catch the eventual mainstream backlash against good old fashioned symbolic AI. :)

But that aside, I’m finding your OP - especially given its contentious title and liberal name dropping - rather confused. If you have some particular thesis, it is lost on me.

Perhaps you can have a go at clarifying how a physicalist conception of qualities says something about a physicalist conception of qualia. I fear that there is only some sleight of tongue at work here.

You see, in my view, qualities are the general essences that science would name - the basic categories of substantial being like gravity, time, energy, entropy, work, etc. And then what makes that naming of entities actually scientific is they are able to be quantified in terms of measurements. We can relate time and energy as physical qualities because we also know how to measure them in terms of seconds and joules.

So the dichotomy (or binary) of quality~quantity is about the general vs the particular, the general theoretical essence and the particular measurement framework which deals with its extension in a world (of time and spatial dimensionality).

But qualia, from philosophy of mind, is something else. It is the atomisation of experience that just wants to reduce that general quality - experience - to a named variety of particular kinds or forms of experience. It builds in a Cartesian dualism by design. It is a way of talking meant to forever frustrate a deflationary neurocognitive approach to “the mind”.

So really, it is a bit of a fraud. A cunning ruse. If you get folk talking seriously about qualia, they have already lost the battle against dualism. The whole Chalmerian enterprise was a rhetorical trick that derailed philosophy of mind in the mid 1990s (in my view).

The better answer was the embodied cognition movement that then followed. But as I say, for me personally, that had already happened. Even early cog sci had an enactivist flavour with folk like Ulric Neisser. And you couldn’t get more mainstream than the “father of cog sci”. ;)

Anyway, again you seem to be making some play on the notion of qualities and qualia. To me, this is where a general physicalist monism and a lingering Cartesian dualism are in fact in direct opposition to each other, and so not a point at which they could be joined. Perhaps you can clarify your thesis in this light. -

David HumeI much prefer my question. One hopes not to need celestial mechanics and Bayesian Inference in order to plan one's breakfast with confidence. — Banno

Focus, Banno. Breathe deeply and focus. :) -

David HumeDifferent question. I was emphasising what makes it reasonable to believe in causal continuity. You are now asking the empirical question of where is the counterfactual that would cause you to doubt that continuity in some particular circumstance.

You also seem to miss the important point. We do know that catastrophes can befall even sunrises. Supernovas are just one such possibility.

And yet, even then, we now have mathematical-strength accounts that make predictions even about such unpredictability. -

David HumeThis is just a failure of the atomistic paradigm, it does not refute the simple fact that effects are the result of causes. — charleton

So you have a simple deterministic account of the quantum eraser experiments that doesn’t involve retrocausality or some kind of outlandish multiverse metaphysics?

Something has to give when faced with the evidence of quantum contextuality as a causal thing. -

David HumeWhy is it reasonably probable that the past predicts the future? Because the constraints or deep structures that generate patterns tend to have been built up bit by bit over a long history. For that historic weight of constraints to change, it seems probable that it would therefore have to be picked apart slowly in the same fashion - bit by bit.

But also, we know from empirical observation of nature, and now logical models of that nature, that catastrophic collapse can occur. What took a long time to build up, can also collapse in sudden and predictably unpredictable fashion.

So the world is actually far more interesting than Humean and Newtonian notions of determinism and probability could know.

We have new models of probability - non-linear and chaotic ones - that change the good old Humean debate beyond recognition anyway ... even after we have abandoned rigid deduction in favour of Bayesian induction as an epistemic foundation.

apokrisis

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum