Comments

-

I’ve never knowingly committed a sinGod has never revealed his will to me. — Art48

Obviously the Christian response is to say that, well, that is what the Bible is, including the gospel of Jesus Christ. The Bible is the revealed word of God. Of course, you choose not to accept that, and that choice is perfectly within your rights, and I wouldn't try to persuade you. You choose to believe that Catholic Priests are expressing their ideas, arising from their personal conviction, and that religion is all man-made, and not revealed truth at all. Again, perfectly within your rights to believe that, and if you challenged them to prove otherwise, and considering the attitude you bring to the table, they in all likelihood would never succeed. And they would say, well, God's will has indeed been revealed, but you chose not to believe it.

But for some reason I am reminded of an anecdote. A parish church is sorrounded by a once-in-a-lifetime flood, but the priest refuses to leave, saying, "God will save me."

The water keeps rising, and begins to lap at the door. A crew in a rubber dinghy comes by and offers him a ride to safety. The priest declines, repeating, "God will save me."

The water continues to rise, and after some time the priest has been forced into the bell-tower. A rescue helicopter arrives and the crew shout to him through a loud-hailer and offer to lower a rope. Again, the priest waves them off, insisting, "God will save me."

But a short while afterwards, the floodwaters overwhelm him and he drowns.

When he reaches heaven, the priest asks, "Why didn't you save me?" He gets the reply, "We sent a boat! We sent a helicopter! What more did you want?" -

The Mind-Created WorldWhat we tend to forget is that every object can also be a subject, — Ludwig V

How so? Subjects are invariably sentient beings are they not? Tables and chairs and billiard balls are objects, but how are they subjects of experience? Isn’t saying that a version of panpsychism?

now we are facing a "hard problem" that appears to have no solution. The framework that establishes the problem has to go. — Ludwig V

Precisely!

I don't quite understand this — Ludwig V

What I meant was that Descartes, in dividing the two substances, material and mental, placed them side-by-side, as it were. And whilst any of us can see and interact with material substance, the existence of ‘res cogitans’ is conjectural, and the proposed ‘interaction’ between the two ‘substances’ problematic. It sets the stage for the elimination of the mental, which is basically what subsequently developed, most directly expressed by ‘eliminativism’.

This criticism is not novel to me, by the way. As I mentioned in another thread, it’s also related to what Husserl said about Descartes, even while crediting him as the founder of transcendental philosophy.

Not to create a physical world from scratch, but to create a metaphysical model of the world that we sense (feel) and make-sense of (comprehend). — Gnomon

Notice the duality you introduce between model and world.

The realization that prompted this essay is basically that of the primacy of experience - but unlike much empiricist philosophy, without bifurcating the domain of experience into subjective and objective. You and I have both read Charles Pinter’s book Mind and the Cosmic Order which I think supports a similar view. -

Rings & BooksI will add, two of my direct family owe their health and well-being to neuroscience. I’m not at all sceptical about its medical and therapeutic benefits. But I’m profoundly sceptical about its relevance to philosophy per se.

-

Rings & BooksI find it interesting to find out about the insights of philosophers with regard to thinking, when those philosophers didn't have the advantage of modern neuroscience in making sense of what is going on. — wonderer1

Don’t you think that is just a tad ‘scientistic’?

Have you ever read anything about the well-known book The Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience, Bennett and Hacker? -

Mindset and approach to reading The Republic?It can be seen, but not demonstrated. — Count Timothy von Icarus

What I get from this, is that this is something that can only be known first-person, as it were. Not that it’s personal in any sense, but (as Buddhists say) ‘only knowable by the wise’. The wise are like finely-tuned instruments which can detect what others do not. But then of course to those who don’t know it, it might well sound like ‘moonshine’, as Socrates also says.

it's less clear if man, hoping to "become like what is most divine," can ever reach that goal, which is why Aquinas has to add infused contemplation/grace into the equation in his commentary on the Ethics to allow the human being to actually achieve happiness in the beatific vision. — Count Timothy von Icarus

‘Through a glass, darkly’ is the Biblical expression. In the Christian faith, it is something that is only seen on the other side of death, although in the Christian mystics, death might be understood symbolically as representing the ‘death of self’. All of which belongs to another age of mankind altogether. -

Exploring non-dualism through a series of questions and answersAll I said was, she acknowledges it. The point being, to gesture towards ‘the atom’ as a purported physical fundamental unit fails to recognize the indeterminate nature of so-called sub-atomic particles. Anyway it’s off-topic.

-

Exploring non-dualism through a series of questions and answersYes - at one point Lawson asks her what her interests are, aside from her ‘very successful YouTube career’ to which she demurs. She says she’s interested in a fundamental research program - something is missing or wrong with quantum physics, and the observer problem ought to be eliminated. (I’m not able to re-listen at the moment, but I know she said it.)

//around 16:30 “…which will do away with this measurement problem….” -

Mindset and approach to reading The Republic?Terrific post, thanks Count. I think that covers a lot of points that I have been struggling with, I’m on the road at the moment but will come back to it later.

-

Exploring non-dualism through a series of questions and answersIt's a fact. I listened to Hillary Lawson interview Sabine Hossenfelder yesterday, and she says her main research interest, aside from her very successful youtube channel, is somehow eliminating 'the observer problem'. That, and the ontological status of the wave-function (which which it is intimately connected) are still outstanding issues in philosophy of physics. You are, of course, free to ignore or deny it but it doesn't negate it.

-

Exploring non-dualism through a series of questions and answersendlessly swirling atoms — 180 Proof

atoms which have no definite existence until they're observed, what's more. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyNo, not that. The problem of personal identity across time. — RogueAI

The article I linked to mentions perdurance. That has to do with anything - and it doesn't have to be a being - maintaining identity through time even as some or all of its component parts are changed (per Ship of Theseus).

I was lamenting that there's no way to test what is actually going on- to know if it is reincarnation, or some form of ESP. — Relativist

Stevenson acknowledges that. It's why he says his data doesn't prove that reincarnation has occured.

It's probably worth acknowledging the Buddhist view of rebirth. As a matter of dogma, Buddhism denies that there is an eternally-existing self that migrates life to life. However, and paradoxically, rebirth is still fundamental to the religion. Consider the selection of lamas in Tibetan Buddhism, where children are shown artifacts from a purported previous incarnation, if they recognise them it's taken as evidence of their identity - even though there is no self or soul that migrates! Many would say it's evidence of a contradiction in Buddhism, but they say that a rebirth is more like a recurring pattern of existence - there's actually a rather lovely Sanskrit term for it, 'citta-saṃtāna':

Citta-saṃtāna (Sanskrit), literally "the stream of mind",[3] is the stream of succeeding moments of mind or awareness. It provides a continuity of the personality in the absence of a permanently abiding "self" (ātman), which Buddhism denies. The mindstream provides a continuity from one life to another, akin to the flame of a candle which may be passed from one candle to another:[4][5][a] William Waldron writes that "Indian Buddhists see the 'evolution' of mind i[n] terms of the continuity of individual mind-streams from one lifetime to the next, with karma as the basic causal mechanism whereby transformations are transmitted from one life to the next."[6]

According to Waldron, "[T]he mind stream (santāna) increases gradually by the mental afflictions (kleśa) and by actions (karma), and goes again to the next world. In this way the circle of existence is without beginning."[7] — Wikipedia

So that actually dovetails rather well with 'perdurance' theory, which could be summarised as 'not the same, but also not different'.

(Incidentally, William Waldron is a go-to scholar in this area, when I did Buddhist Studies, I emailed him and got a nice reply, with some unpublished articles attached. His latest book is this one.) -

AGI - the leap from word magic to true reasoningQuestion: Further to this discussion one of the points I would make is that, in order for an AGI system to fully realise human capacities, it would need to be a subject of experience. And no current systems, including ChatGPT, are subjects of experience, as such. They emulate what a subject might say, but they're not actually subjects as such, right?

ChatGPT: That's a very astute point, and you're correct. Current AI systems, including ChatGPT, are not subjects of experience—they do not have subjective experiences, consciousness, or awareness. These systems are designed to process input data and generate responses based on patterns they have learned from large datasets. They can emulate human-like dialogue and even imitate styles of thinking or arguing, but this is fundamentally different from actually experiencing or understanding these processes.

The notion of an AI being a "subject of experience" involves concepts of consciousness and subjective experience that are, at present, beyond the capabilities of AI. The idea of subjective experience, often referred to philosophically as "qualia," is closely tied to consciousness—having personal perceptions, feelings, and experiences that are inherently private and firsthand.

For an AGI to truly realize human capacities as you've mentioned, it would need to not only process information and solve problems efficiently but also possess consciousness or some form of experiential understanding. This leap from a highly advanced computational tool to a being with subjective experiences raises profound questions about what consciousness is and whether it can be artificially created or replicated.

Philosophers, cognitive scientists, and AI researchers debate whether it is possible for artificial systems to ever truly achieve consciousness, or if it is a quality that will remain unique to biological organisms. Some argue that consciousness might emerge from sufficiently complex systems, while others believe it requires a specific kind of biological substrate or that it is fundamentally inexplicable and thus inimitable by machines.

In any case, the development of AI systems that can claim genuine subjectivity and consciousness would represent a monumental shift not only in technology but in our understanding of what it means to be 'alive' or 'aware.' This continues to be a fascinating area of inquiry at the intersection of technology, philosophy, and ethics.

And that sure sounds like a Hard Problem ;-) -

Exploring non-dualism through a series of questions and answersNirvana is the realization of impermanence, no absolutes, and emptiness through and through. — PoeticUniverse

But it's emphatically also not nihilism, that idea that nothing is real, which is always rejected as one of the 'extreme views' (and even though many Hindus accuse Buddhism of nihilism). So it's unwise to declare what Nirvāṇa is. Only a Buddha knows that. -

AGI - the leap from word magic to true reasoningThe only way I can think of is to imbue it with a chronic angst or fear of death or suffering — Benj96

For it to fear death, it would have to be alive. It would have to be a being, not a simulcrum. But then you'd have to consider its rights as a being. And besides, if it were a being, what if it decided it couldn't bear this mode of being? It's more than a can of worms! Now we're in Blade Runner territory. -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyIt's frustrating because there seems to be no way to test any theories. — Relativist

But if a child's alleged memories of a previous life can be validated against documentary records and witness testimony, that amounts to some form of verification. (I've discussed Ian Stevenson previously but it usually generates such hostility that I refrain.) However his activities spanned a 30 year period and many thousands of cases. He himself never claimed to have proved that cases of re-incarnation occur, but that the evidence 'suggests it'. My knowledge of it is limited to a book I read about him by a journalist who travelled with him, and one of his publications borrowed from a library. Seems legit to me, but to a lot of people, not only is it not true, but it can't be true. Whereas I'm open to the idea.

Do you think idealism solves it? Did you see the conversation with Kastrup and Koch yet? — RogueAI

I watched about half of it, but I didn't notice anything about this topic. Besides, I don't know if idealism 'solves' the question of re-incarnation. Perhaps Sheldrake's morphic resonance at least provides a candidate for a medium of transmission. He says, as you will recall, that nature forms habits, that memories are not merely encoded in brains but in morphic fields. One question I've got is this: science only discovered electromagnetic fields in the mid-19th century. Until then, we had no idea of such a phenomenon, now they're thought to be more fundamental than sub-atomic particles. So what if there are fields other than electro-magnetic? How would they be detected? Electromagnetic fields are detected using instruments that register electric current. Even if there were morphic fields, presumably they are not detectable by those instruments, so they might exist undetected. There have been ideas like this in esoteric and occult circles for millenia. Maybe they're on to something, but it's a taboo subject as far as the mainstream is concerned. -

Information and RandomnessRight. But the error I think the Verasatium presentation makes is then to equate non-compressibility with information - that a completely random string carries the greatest amount of information, because it can't be compressed. Whereas I think a random string embodies no information whatever.

That said, I frequently watch that Youtube channel, he's a very good popular science commentator. But I think this was not one of his better efforts. -

What is a strong argument against the concievability of philosophical zombies?Oh, sorry, I re-quoted a question originally posed by @180 Proof (but it doesn't change my response, such as it is.)

-

Rings & BooksOh yes, I perfectly agree. I'm a staunch advocate for one or another form of idealism on this forum, see The Mind-Created World which I think I posted before you joined (and most enjoying your contributions, by the way.)

-

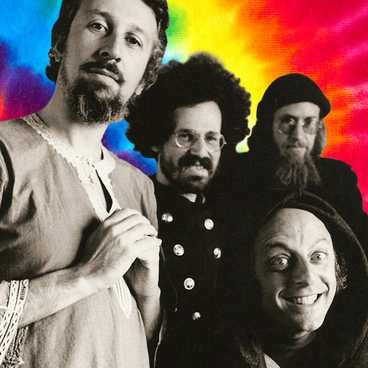

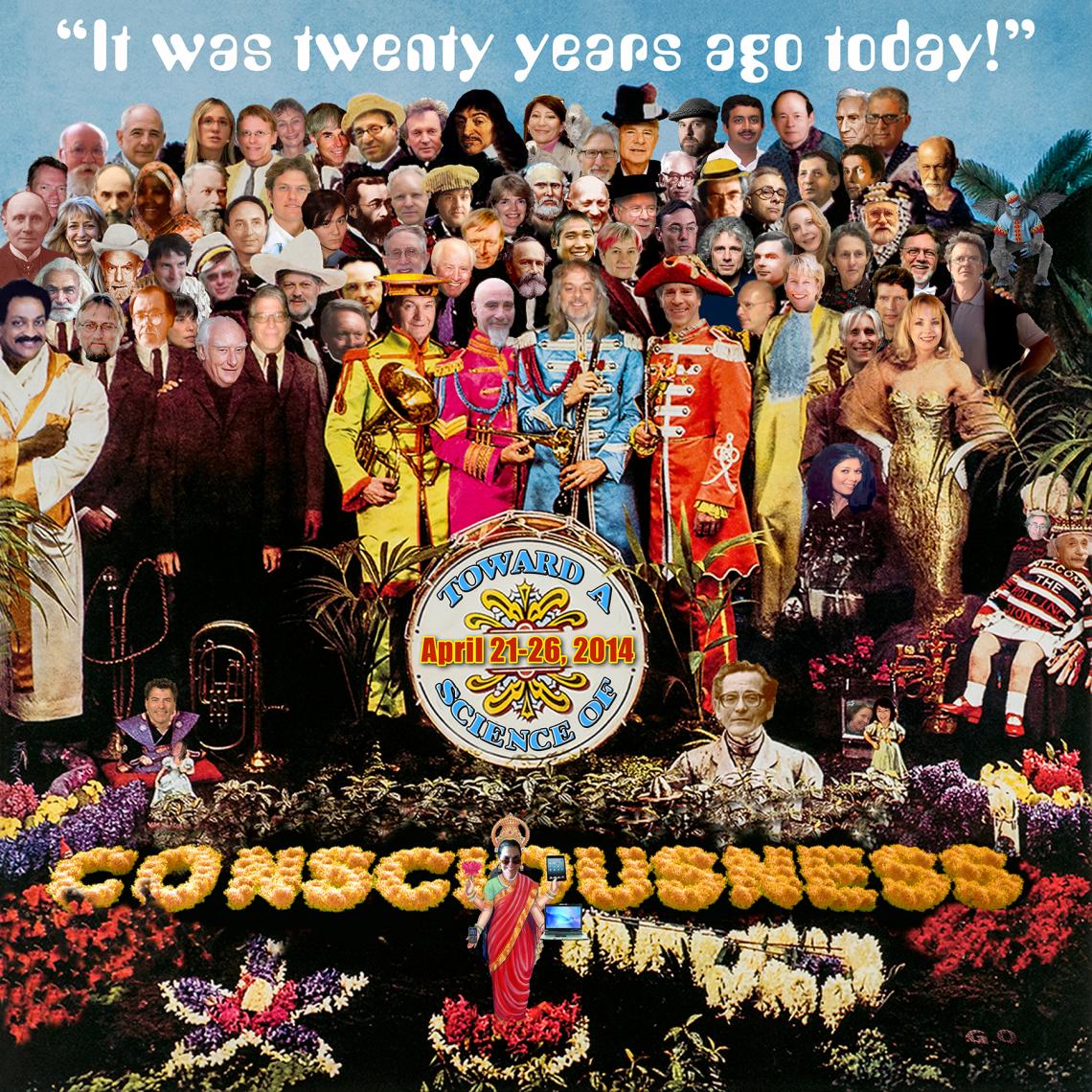

What is a strong argument against the concievability of philosophical zombies?The first of the Towards a Science of Consciousness, a bi-annual spielfest held at Uni of Arizona Tucson (next one is this month!). If you zoom in on that ‘album cover’ it comprises photos of many of the main attendees, with David Chalmers in the middle. (His ‘Facing up to the problem of Consciousness’ was one of the main motivators for the conference. To his right is Stuart Hameroff who is known for the OrchOR model co-developed with Roger Penrose. I can identify a few of the others also.) But the thing which grabbed me about that, is how hippies have now become part of the mainstream, hence the salute to Sgt Pepper's. There's another great book along those lines, How the Hippies Saved Physics, David Kaiser, which features this great photo of the Fundamental Fysiks Group

Standing, left to right: Jack Sarfatti, Saul-Paul Sirag, Nick Herbert;

Bottom right: Fred Alan Wolf.

Hence the mainstreaming of the counter-culture in physics and philosophy of mind.

Zombies be damned :flower: -

AGI - the leap from word magic to true reasoningIn the words of Yann LeCun (a leading AI technologist) "researchers need to work on 'objective-driven' AI with the ability to reason and plan about the world, rather than just work on words alone."

So what does it mean to have an "objective", and "reason" towards a resolution instead of just predict one? — Benj96

Does it mean, something has to matter to it? Humans and other creatures are driven by basic needs, but also by desires, plans, intentions and goals. I think the human capacity to reason is also goal-oriented in that way, and so ultimately driven by necessity. How could such attributes be genuinely embedded in an artificial system?

On Pierre-Normand's suggestion, I put it to ChatGPT 4, which responded as follows:

RevealYes, it's a very insightful question, highlighting some of the most significant challenges and philosophical inquiries in the development of artificial intelligence, especially concerning the aspirations toward artificial general intelligence (AGI). Let's explore the concepts mentioned and respond to some of the questions raised.

Objective and Reasoning in AI: In AI, an "objective" typically refers to a specific goal that the system aims to achieve, programmed by humans. For example, the objective of a chess-playing AI is to win the game. This is in contrast to human objectives, which are often multifaceted and can change dynamically based on the situation and internal motivations. "Reasoning" in AI terms means the capability to make inferences or deductions based on data and a set of rules, or more advanced forms of reasoning that involve planning or decision-making based on predicting future states.

However, current large language models (LLMs) like the one you're interacting with now do not genuinely reason in the human sense. They generate responses based on patterns learned from data, aiming to provide the most statistically likely answer, not necessarily to understand or reason through topics as humans do.

Goal Orientation and Data: Humans use a relatively limited dataset (our personal experiences and knowledge) but are incredibly efficient at generalizing from this data, thanks to our biological evolution and cognitive development which grant us the ability to reason abstractly, plan, and adapt. We're not just processing information but also actively learning and applying knowledge creatively and adaptively. For AGI to reach a similar capability, it would need not only access to vast amounts of data but also the ability to abstract, generalize, and reason beyond mere data retrieval or pattern matching.

Reiterative Automaticity: The concept you referred to as "reiterative automaticity" suggests that AGI should be able to autonomously modify its algorithms based on new information or changes in its environment, much like how humans learn from experiences and adjust our behavior. This type of learning and adaptation is a step beyond what current AI systems are capable of, where most adjustments to AI behavior are manually programmed by developers.

Compression of Algorithms and Data Efficiency: The idea that AGI should operate with the same or less data than a typical human to reason effectively is a profound one. It suggests an efficiency of processing and decision-making that AI systems currently lack. Current models require extensive data and computational power, whereas humans can make complex decisions with much less explicit information, often relying on intuition or subconscious processing.

Objective and Free Auto-Self-Augmentation: Giving AI an "objective" while also allowing "free auto-self-augmentation" touches on the core challenge of creating an AI that can set its own goals and adapt its methods autonomously. This raises both technical challenges and ethical questions. How do we ensure that an AI's self-set goals are aligned with human values? How do we manage and govern systems that can operate independently?

Lastly, whether this could be the difference between something that feels/experiences and something lifeless touches on the philosophical debate about consciousness and experience in artificial entities. This is a complex question that straddles technology, philosophy, and ethics.

In conclusion, moving towards AGI involves not just technical advancements in how AI systems process and handle data but also profound insights into the nature of intelligence, consciousness, and the ethical frameworks we construct around autonomous systems. It's a fascinating field with much to explore and discuss! — ChatGPT4

(I noticed the use of the pronoun ‘our’ in relation to human capacities). -

Rings & BooksI've always thought that Kant essentially accepts Berkeley, — Ludwig V

I have read that Kant was infuriated by those critics of his first edition who accused him of basically re-cycling Berkeley's idealism, to which end he included a lengthy section in the second edition, 'A Refutation of Idealism' (see e.g. this reference.) -

What is a strong argument against the concievability of philosophical zombies?mind is a 'mystery' too intractable for science, even in principle, to explain? — bert1

(Apologies for the delay in responding, I only just noticed the question from 15 days ago.)

Science construed as dealing solely with objective phenomena. But the grounds are rapidly shifting. I'm spending a lot of time nowadays perusing various Internet speilfests and panel discussions which are challenging the over-arching physicalist/objectivist paradigm that has dominated science until now. Phenomenology, analytical idealism, post-modernism and non-dualism (to mention a few) are challenging the physicalist paradigm and conception of the nature of science.

Who remembers the poster from the 2014 Tucscon Science of Consciousness conference?

'It was twenty years ago today'. And that was ten years ago! -

Evidence of Consciousness Surviving the BodyStevenson's research on children who remember their past lives might be of interest. Of course it's wildly controversial and a taboo subject but he assembled a large data set. See this article.

-

The Mind-Created WorldA bunch of chalk on a blackboard, not a universe. — Count Timothy von Icarus

True - but that said, it is remarkable that the equations of general relativity can be captured on a single piece of paper. I don't think Thomas Nagel (or myself) wants to deprecate the astonishing reach of mathematical physics, so much as to point to what it assumes, and what it leaves out. Mind you, Wheeler's 'participatory universe' is one of the ways that these kinds of reflections became apparent from within science itself. -

The Mind-Created WorldFrom here. I will try and respond to this here because it is more relevant to this thread than to the one from which it originated.

If the physical is naturally understood to have substantial or substantive existence, and it is upon that idea of substance that the notion of reality is founded, and the idea of a mental substance is untenable, then what justification would we have for saying that anything non-physical is real?

The alternative to eliminative physicalism would be to say that mental phenomena are real functions of some physical existents, and that the only sense in which they are not physical is that they do not (obviously) appear as objects of the senses. — Janus

I think what you mean by 'substantial' and 'substantive' is 'tangible' and/or 'measurable'. Those are the empirical criteria for what is considered to exist.

There are many things that could be said, but as the question originated in a thread about Descartes, it might be noted at the outset that the idea of 'substance' and 'substantial' in philosophy is not an empirical one. Rather it originates with Aristotelian/Platonic metaphysics, wherein 'substance' was 'a thing whose existence is independent of that of all other things, or a thing from which or out of which other things are made or in which other things inhere' (Brittanica. It is, of course, true, that the classical idea of substance has fallen out of favour except for with adherents of Thomism and perhaps other modern forms of hylomorphism, for which see this daunting index.)

That said, I think that the traditional notion of substance became associated with, or displaced by, the objects of physics, as a part of the 'Scientific Revolution'. After all, the hallmark of the 'new science' was (1) the identification of the 'primary attributes' of matter as the principle subject-matter of physics and (2) the supposedly universal scope of the new physics (i.e. Galilean-Newtonian) to all such objects of analysis. This leads to the paradigm that I also quoted in the thread from which this query originated:

The modern mind-body problem arose out of the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, as a direct result of the concept of objective physical reality that drove that revolution. Galileo and Descartes made the crucial conceptual division by proposing that physical science should provide a mathematically precise quantitative description of an external reality extended in space and time, a description limited to spatiotemporal primary qualities such as shape, size, and motion, and to laws governing the relations among them. Subjective appearances, on the other hand -- how this physical world appears to human perception -- were assigned to the mind, and the secondary qualities like color, sound, and smell were to be analyzed relationally, in terms of the power of physical things, acting on the senses, to produce those appearances in the minds of observers. It was essential to leave out or subtract subjective appearances and the human mind -- as well as human intentions and purposes -- from the physical world in order to permit this powerful but austere spatiotemporal conception of objective physical reality to develop. (Mind and Cosmos, Pp35-36) — Thomas Nagel, Mind and Cosmos, Pp 35-36

I am proposing in this OP, that this amounts to more than just a theoretical paradigm - it's also a worldview, and one which is essentially the default view of secular, scientifically-informed culture. I also claim that an implicit assumption of this worldview is the 'subject-object' relationship - it takes for granted or assumes our status as intelligent subjects existing in a world of objects (and other subjects). Within that paradigm, 'objectivity' is the criterion for what is real or existent; what is 'objectively true' is what 'exists when you stop believing in it', as Philip K. Dick put it.

Here, this point is relevant:

...physics reveals a physical world that is almost completely insubstantial. "Substantial" and "real" have a meaning in the context of physics, but not one that meets the demands of this philosophical wild-goose chase. Berkeley was wrong about many things, but about this, he was right. — Ludwig V

With which I agree. I take his main point to be a reference to the well-known 'observer problem' in quantum physics, which has undermined the whole idea of the 'mind-independent reality' of the objects of quantum physics, although I don't want to go into the whole 'interpretations of physics' tangle.

So what I was arguing in the other thread is that a consequence of Cartesian dualism is to depict mind (res cogitans) as something that exists within this subject-object paradigm, which is the scientific paradigm, and which is the only one we know or are confident of. The question becomes, how do you demonstrate or prove the existence of such a 'thinking thing'? Why, you can't! It's a specious concept. So what are we left with? The other half of Descartes' duality, namely, res extensia, extended matter, which Modern Science has proven so extraordinarily adept at analyzing and manipulating. (This is the sense in which I agree with Ryle's categorisation of Descartes' error as a category mistake, although I don't accept his remedy.)

Mind is not something that exists in this paradigm, except for as a product of the brain, an epiphenomenon, or an emergent attribute of what really does exist - which is the physical. That I see as the common-sense, mainstream view (which eliminativism takes to the most extreme, but also most consistent, position.)

This is why the argument in the OP says that an alternative to this view is a perspectival shift, a different way of seeing, which also turns out to be a different way of being. I'm pretty much in agreement with Bernardo Kastrup's analytical idealism in that regard, but it's really important to understand that this doesn't mean establishing that mind is something objectively existent. -

Exploring non-dualism through a series of questions and answersI'll add, I think these subjects *are* very difficult to fathom, as the Buddha's quote. After all, those who sought to fathom them often gave away everything in order to pursue it.

When I was much younger, I had the foolish idea that Zen enlightenment, satori, was a simple matter - probably from reading too much of Alan Watts. I recently read an essay by an Australian poet and esotericist, Harold Stewart, who emigrated to Kyoto Japan where he spent the last decades of his life. He observes:

But many Western enthusiasts for what they imagine to be Zen have never actually come into contact with this branch of the Buddhist Tradition as it still exists and functions in the Far East. ....Those few who took the trouble to visit Japan and begin the practice of Zen under a recognized Zen master or who joined the monastic Order soon discovered that it was a very different matter from what the popularizing literature had led them to believe. They found that in the traditional Zen monastery zazen is never divorced from the daily routine of accessory disciplines. To attenuate and finally dissolve the illusion of the individual ego, it is always supplemented by manual work to clean the temple, maintain the garden, and grow food in the grounds; by strenuous study with attendance at discourses on the sutras and commentaries; and by periodical interviews with the roshi, to test spiritual progress. Acolytes are expected to develop indifference to the discomforts of heat and cold on a most frugal vegetarian diet and to abstain from self-indulgence in sleep and sex, intoxicating drinks and addictive drugs. Altogether Zen demands an ability to participate in a communal life as regimented and lacking in privacy as the army.

I read a few accounts of Westerners who did spend time in Zen monasteries, like Jan Westerling's 'An Empty Mirror.' And it's extremely taxing. The Japanese are famously strict disciplinarians and the daily routines are exacting - one of those visiting Westerners (can't remember which) became so severely malnourished he almost died because the monks were given only a few minutes to eat.

Not that I've abandoned any effort, I'm still keen to learn and practice, and some things I've learned have sunk in. But it's a hard row to hoe. -

Exploring non-dualism through a series of questions and answersupon its obtainment the conventional truth of phenomena (such as of phenomena-dependent pains and pleasures together the our apprehension of selfhood) will also persist in this state of ultimate being - for the two truths were roughly stated to be one and the same. Yet, as expressed, I can currently only presume this to be wrong, for it is contrary to what Nirvana without remainder is described to be — javra

In the early Buddhist texts, speculation about 'what it must be like' is discouraged. In later Buddhist texts, like the Diamond Sutra, whether Nirvāṇa is something that can really be obtained is an open question.

As far as Advaita is concerned, my reading is limited mainly to the teachings of Ramana Maharishi. At the end of his life, he developed a tumor on his arm which turned out to be the cause of death. When asked if it was painful - it certainly looked pretty gruesome, according to the accounts of those around him - he would reply 'I feel the pain, but it doesn't hurt'.

From a philosophical perspective, which is inevitably quite shallow, his sense of the Self is such that the pain experienced on a physical level no longer seems all-pervading, as it would do to most of us who completely identify with the physical. I suppose you could say that pain is then experienced in a much broader context, as his sense of the Self transcends the physical. But that doesn't mean he's simply numb or unfeeling.

(In all this I'm only reflecting what I've read, I don't claim to have any special insight or realisation.) -

Exploring non-dualism through a series of questions and answersIncidentally I read an Aeon essay some time back from a philosopher who is interested in dialetheism, Graham Priest, on Buddhist logical paradoxes, you can find it here https://aeon.co/essays/the-logic-of-buddhist-philosophy-goes-beyond-simple-truth . (I couldn't really understand it but others might find it helpful.)

-

Exploring non-dualism through a series of questions and answersNāgārjuna's philosophy posits that the ultimate truth is not a separate, higher realm of reality but is instead the real nature of the conventional world when it is seen without the distortions of conceptual thought. In other words, ultimate reality is not an alternative to conventional reality; it is the insight into the emptiness (śūnyatā) of inherent existence in all phenomena. This realization leads to the understanding that what we consider to be fixed and separate entities are actually interdependent and devoid of intrinsic nature (svabhava).

Thus, the distinction between conventional and ultimate truths is a skillful means (upāya) to guide beings towards enlightenment. For unenlightened beings, the world appears in dualities and distinctions. For those who have realized enlightenment, however, these dualities are seen as expressions of a single, indistinguishable reality that is empty of inherent existence. The "two truths" are therefore not ultimately separate; they are two ways of perceiving the same reality, contingent upon one's level of insight.

Like I said (somewhat tongue-in-cheek) 'burn after reading' ;-) -

Exploring non-dualism through a series of questions and answerswhat I was fishing for here is any rational criticism of the presented necessity that non-dualism, this regarding the world as it’s known, entails a duality between a) a real (or ultimately real) and non-dual fundamental essence and b) a contingent fundamental essence of phenomena (etc.) which brings about duality in the world and which is ultimately illusory in full. — javra

I haven't read Loy's book in full, either, but I would be surprised if he doesn't cover this.

But the epistemology of non-dualism is a very subtle and difficult thing to understand. That's because at its core, it arises out of dhyana, meditative stillness, which is the practical negation or transcendence of self-and-other. The early Buddhist texts constantly repeat a fundamental theme, which is that of dependent origination, the causal chain which leads to suffering, and the seeing through of it by insight. But the insight is always inseperable from praxis - the three legs of the tripod are sila, prajna, samadhi, meaning right action, right wisdom, and meditative absorbtion. But that is not presented or understood as being something easy to attain or understand, it requires constant application and deep commitment. So it's a form of practice.

Actually if you read Pierre Hadot, ancient philosophy in the West was also like this:

For Hadot...the means for the philosophical student to achieve the “complete reversal of our usual ways of looking at things” epitomized by the Sage were a series of spiritual exercises. These exercises encompassed all of those practices still associated with philosophical teaching and study: reading, listening, dialogue, inquiry, and research. However, they also included practices deliberately aimed at addressing the student’s larger way of life, and demanding daily or continuous repetition: practices of attention (prosoche), meditations (meletai), memorizations of dogmata, self-mastery (enkrateia), the therapy of the passions, the remembrance of good things, the accomplishment of duties, and the cultivation of indifference towards indifferent things. Hadot acknowledges his use of the term “spiritual exercises” may create anxieties, by associating philosophical practices more closely with religious devotion than typically done. Hadot’s use of the adjective “spiritual” (or sometimes “existential”) indeed aims to capture how these practices, like devotional practices in the religious traditions, are aimed at generating and reactivating a constant way of living and perceiving in prokopta (=preceptors, students), despite the distractions, temptations, and difficulties of life. — IEP

Secondly, the relationship between reality and illusion is also very subtle. In the Madhyamaka of Nāgārjuna, there is 'the doctrine of two truths', the domain of conventional reality, Saṃvṛtisatya, in which all sentient beings are situated, but then the domain of ultimate reality, Paramārthasatya which is the higher truth perceived by the Buddhas. But part of this doctrine is that (1) these are not ultimately two and also that (2) the principle of emptiness (śūnyatā) is also empty.

There's a saying in both Advaita and Buddhism, that wisdom-teachings are like the stick you use to stoke the fire. Once the fire is burning, then the stick can be thrown into it. Like, 'burn after reading'. All of that goes back to the Buddha's 'parable of the raft', which compares the teaching to a raft, used to cross the river of suffering, but not to be clung to. See the Zen calligraphy, Hui Neng tearing up the Sutras:

I think the way to see all this, is that awakening is something like a deep gestalt-shift, a complete shift or reversal of perspective, so that from the 'conventional' perspective, there are 'two truths', conventional and ultimate, but from the 'higher' perspective, the distinction vanishes. The world appears as multiplicity to the conventional mind, but is seen as being ultimately one in the unitive consciousness. Of course that is a very hard thing to grasp also, as the Buddha says to one of his philosophical interlocutors, 'Deep, Vaccha, is this dharma, hard to see, hard to realize, tranquil, refined, beyond the scope of conjecture, subtle, to-be-experienced by the wise.' -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)Meanwhile Trump is holding a press conference on Election Integrity on Friday, some he’s said to ‘care deeply about’ :vomit:

-

Rings & BooksI recommend Pierre Hadot's "Philosophy as a Way of Life" — Fooloso4

From which:

Philosophy in antiquity was an exercise practiced in each instant. It invites us to concentrate on each instant of life, to become aware of the infinite value of each present moment, once we have replaced it with the perspective of the cosmos. The exercise of wisdom entails a cosmic dimension. Whereas the average person has lost touched with the world, and does not see the world qua world, but rather treats the world as a means of satisfying his desires, the sage never ceases to have the whole constantly present to mind. He thinks and acts within a cosmic perspective. He has the feeling of belonging to a whole which goes beyond the limits of his individuality. In antiquity, this cosmic consciousness was situated in a different perspective from that of scientific knowledge of the universe... . Scientific knowledge was objective and mathematical, whereas cosmic consciousness was the result of spiritual exercise. — Pierre Hadot, PWL, pa 273

(Incidentally just prior to this passage, Hadot says Descartes and Spinoza remained faithful to philosophy as 'the practice of wisdom'. Spinoza, in particular, despite being claimed as the harbinger of secular naturalism, was still within the current of Judaic mysticism, and his 'intellectual love of God' very much in keeping with Hadot's depiction of cosmic consciousness.)

Compare also Thomas Nagel:

Plato was clearly concerned not only with the state of his soul, but also with his relation to the universe at the deepest level. Plato’s metaphysics was not intended to produce merely a detached understanding of reality. His motivation in philosophy was in part to achieve a kind of understanding that would connect him (and therefore every human being) to the whole of reality – intelligibly and if possible satisfyingly. — Secular Philosophy and the Religious Temperament -

Rings & Booksthere is no problem conceiving something immaterial that exists by itself unless you are a close-minded physicalist. — Lionino

What kind of 'something'? That's the rub. I'm sure the majority view is expressed by Janus here:

If the physical is naturally understood to have substantial or substantive existence, and it is upon that idea of substance that the notion of reality is founded, and the idea of a mental substance is untenable, then what justification would we have for saying that anything non-physical is real? — Janus

The notion is - mind is the product of the brain, which in turn is the product of evolutionary biology over many aeons of time. Rational sentient beings such as ourselves are therefore a very late arrival in the grand scheme, which is otherwise mindless. Isn't that what practically any sound person believes? -

Exploring non-dualism through a series of questions and answers

You might find this a useful resource: Nonduality, David Loy, a .pdf copy of his book by that name, based on his PhD. You can find more about him on davidloy.org.(FYI, this correlates with parts of something I'm currently working on.) — javra -

Rings & BooksWhat is your claim? — Banno

Again - my claim is that due to the form that Cartesian dualism assumed, that there is a kind of widespread, implicit dualism of mind and body or spirit and matter that is endemic in culture. And that the untenability of the idea of a 'thinking substance' or 'thinking thing' has had huge influence of philosophy of mind ever since, it is one of the principal causes of the dominance of physicalism in mainstream philosohpy (remember your surveys in which only 1% of respondents hold to alternatives to physicalism?) Which is implicit in the question you asked. -

Rings & BooksYou do understand that in your quote, Ryle is setting out his target, not defending a doctrine. — Banno

His target is, explicitly, Cartesian dualism of mind and body. That's the starting point of his book Concept of Mind. Ryle's solution to it is basically beaviourism - that categorisation of mind and body as two separate entities is a category mistake (which is the origination of that term), but then, the philosophy of mind that comes from that is essentially behaviourist.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2024 The Philosophy Forum