Comments

-

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)So the Orange Emperor is gifted a Nobel Peace Prize medal by Maria Corina Machado, leader of the Venezuelan opposition, which had been awarded to her. Never mind that the Committee says that in no way such honours can be transferred! The Emperor will grasp the opportunity. Even though he’s basically disenfranchised Machado after snatching Maduro, declaring that she ‘lacks popular support’. (Oh well, I guess he’s saved the Venezuelans the trouble of having an election as he obviously knows ‘the will of the people’ better than they themselves.)

But what an unbelievably gauche and classless gesture, accepting someone else’s Nobel. With Trump, there’s never any bottom. -

The Predicament of ModernityFair enough. I'd go along with that. But I've got a more specific focus in mind. (I meant by the 'italicized pargraphs' the post directly above your last post, which re-states the thrust of the OP.)

I've gone back and looked at your initial comment in this thread, so I offer the following retrospective response.

I take Wayfarer to mean we are adrift from a culturally imposed overarching purpose. Such overarching purposes were imposed by political elites who throughout most of history were the only literate members of societies. The oppressed illiterate masses had no choice but to at least pay lip service to the imposed values and meanings. To what extent they were genuinely interested in, or were privately opposed to, these impositions remains, and will remain, unknown, precisely because they were illiterate. — Janus

I take this to imply that the hidden purpose of my argument is to 'restore the ancient order'- harking back to some supposed 'higher knowledge' which was imposed on the masses by the aristocracy and the Church ('political elites'.) This is the way you often intepret my posts, and I can sort of understand why. After all the so-called 'perennialists' who invoke the 'wisdom traditions' are often political reactionaries. So this kind of analysis can easily be associated with them. But, not my intent. I think I'm fully cognizant of the way that the knowledge we have now prevents any kind of return to a traditionalist mindset. Yet at the same time, those perennial philosophies must still remain perennial (otherwise, they never were!)

And also, it is true that Biblical narratives provided an historical framework which could be interpreted as an imposed political order and hence an imposed 'purpose'. indeed the European Enlightenment was largely inspired as a means to throw of the 'ancien regime' and ending of our self-imposed tutelage (Kant). This has obviously been hugely beneficial in many ways - in that sense, I'm very much a progressive liberal. But at the same time, it has its shadow. And the shadow is precisely the sense of being cast adrift in a meaningless cosmos, the children of chance and necessity, with only our own wits and purposes set against the 'appalling vastnesses of space' (Pascal). That's nearer to what I mean by the 'predicament of modernity'. The resulting idea that 'the universe is meaningless' is very much the product of that mindset. It comes directly from the 'Cartesian Division' that was mapped out in the OP. And yet, it remains a kind of cultural default for much of the secular intelligentsia. That is Vervaeke's 'meaning crisis' in a nutshell.

So I am reacting against the physicalist view, yes. The view that what is real, are the entities describable in terms of physics, and that life and mind are products of, or emerge from, that. If you see the way the division or duality was set up in the first place, then you can see how it is a picture based on an abstraction. That is what this thread is about. -

The Predicament of ModernityGreat! Thanks for that clarification.

You fail to realize it (physicalism) is self-contradictory only on the the assumptions, the strictures, that you place on it. — Janus

Well, they're spelled out in the two italicized paragraphs above. What I'm arguing is that physicalism in its modern form, arose as a consequence of the Galilean and Cartesian divisions between mind and matter, between primary and secondary qualities, and so on. This thesis has been explored in detail in those sources I provided, amongst many others (i.e. Whitehead's 'bifurcation of nature'.) So if you think that is overall mistaken, then how so? -

The Predicament of Modernitythen accuse others who don't agree with your dogmatic strictures of being positivists. — Janus

The only reason I have said that some of your posts are 'positivist', is when they clearly are. Not all the time, but also not infrequently.

Positivism is a philosophy asserting that genuine knowledge comes only from sensory experience and logical/mathematical analysis, emphasizing scientific methods, objective facts, and observable phenomena while rejecting metaphysics, intuition, or faith as sources of truth.

You might explain what about that definition you disagree with.

The 'tendentiously monolithic history of ideas' is summed up in these paragraphs, and is supported by the references provided.

Descartes systematised what Galileo had begun. Taking the measurable world as the paradigm of objective knowledge, he posited a strict ontological division between res extensa—the extended, mechanical substance of nature—and res cogitans—the unextended, thinking substance of the mind. This dualism safeguarded human subjectivity from the reductionism of mechanism, yet it did so at the cost of severing mind from world. Thought was now a private interior realm looking out upon an inert, external nature. The result was a self-conscious spectator of a disenchanted universe: the modern subject—liberated from dogma yet exiled from a cosmos stripped of inherent meaning.

The Cartesian worldview soon became the framework of modern science. Its success lay in treating the natural world as a closed system of mechanical causes, perfectly describable in mathematical terms and open to experimental verification. By excluding subjective and qualitative dimensions from its domain, science achieved unprecedented predictive power and technological mastery. Yet this very exclusion became an implicit metaphysic: reality was equated with what could be measured, while everything else—value, purpose, consciousness—was deemed epiphenomenal, a by-product of the essentially purposeless motions of matter. Thus the Galilean and Cartesian divisions were no longer simply methodological but ontological, shaping the modern sense of the meaning of being. We're all inheritors of those ways of thinking, whether aware of it or not.

Refs: Edmund Husserl, The Crisis of the European Sciences; Thomas Nagel, Mind and Cosmos: Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature Is Almost Certainly False (2012); Michel Henry, Barbarism (1987).

And it's a perfectly defensible historical analysis. -

About TimeI think of myself, in behalf of a possible experience, by abstracting from all actual experience, and from this conclude that I could become conscious of my existence even outside experience and of its empirical conditions. Consequently I confuse the possible abstraction from my empirically determined existence with the supposed consciousness of a separate possible existence of my thinking Self, and believe that I cognize what is substantial in me as a transcendental subject, since I have in thought merely the unity of consciousness that grounds everything determinate as the mere form of cognition. — ibid. B426

Again, a very useful passage, in terms of understanding Kant's view of the matter, and thanks for it.

The repeated use of “mere” and “merely” in that sentence really caught my eye — they’re doing a lot of work.

Kant isn’t just describing the unity of consciousness, he’s also putting a fence around how we’re allowed to think about it. What he’s warning against is a very natural slide: we abstract in thought from all particular experiences, and then quietly slip into thinking that the “I” could exist on its own, as a separate kind of entity altogether outside experience.

So when he says that what we really have is “merely the unity of consciousness” and “the mere form of cognition,” the point isn’t that it’s trivial or unimportant. It’s that it isn’t substantia — a thing or an entity in its own right. It’s a formal condition: the structural unity that makes determinate experience and judgement possible at all. The “mere” is there to stop us reifying it into a metaphysical self or soul.

At the same time, though, this “mere form of cognition” is doing incredibly deep work. Literally pivotal. It’s what makes any experience hang together as experience in the first place. Without it, nothing could count as an object for a subject, and nothing could really be judged or known. So the language feels a bit defensive. In the effort to avoid dogmatic metaphysics, he risks slipping into dogma of another kind.

Which leaves an interesting tension. On the one hand, he insists it’s only formal. On the other hand, it’s the most basic enabling condition of intelligibility that we ever encounter. You can’t help wondering whether it’s really “mere” in any innocent sense — or whether Kant is deliberately bracketing off a deeper way of understanding it in order to avoid drifting back into old-style metaphysics. I think in this vital respect he is leaning too far towards empiricism.

It's also the very point which his later critics (even his friendly critics) used to pry open the 'door to the noumenal' (see this blog post.)

@boundless - I think this might echo some of your concerns. -

Are there any good reasons for manned spaceflight?There'll be no hats. :yikes:

Anyway - my basic point is still, there's an awful lot of basic stuff that needs doing here on Earth, before 'fixing our gaze on distant worlds'. -

Cosmos Created MindHey, I like Gnomon as a person, and he's not a disruptive or antagonistic contributor. But, you know, this forum is a place where ideas go to get criticized.

-

Are there any good reasons for manned spaceflight?They're not cranks. It's published by the Union of Atomic Scientists.

Founded in 1945 by Albert Einstein, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and University of Chicago scientists who helped develop the first atomic weapons in the Manhattan Project, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists created the Doomsday Clock two years later, using the imagery of apocalypse (midnight) and the contemporary idiom of nuclear explosion (countdown to zero) to convey threats to humanity and the planet. The Doomsday Clock is set every year by the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board in consultation with its Board of Sponsors, which includes nine Nobel laureates. The Clock has become a universally recognized indicator of the world’s vulnerability to global catastrophe caused by man-made technologies.

Last week, Putin fired a nuclear-capable missile into Ukraine. -

Cosmos Created Mindthe material/immaterial gap — AmadeusD

The 'material-immaterial' gap is an artefact of Cartesian philosophy, with his 'mind-matter dualism', which has been woven into the fabric of modern culture. That can be understood through examining the philosophy, culture and history of the last several centuries, without having to compare energy with ghosts. The Predicament of Modernity presents that argument in more detail. -

Are there any good reasons for manned spaceflight?I don't think we're at risk of a catastrophe — AmadeusD

Well, I admire your optimism. The Doomsday Clock was last set 28th Jan 2025, at 89 seconds before midnight. -

Michel Bitbol: The Primacy of ConsciousnessSome commentary on the idea of transpersonal subjectivity developed in dialogue with claude.ai

The supposedly "objective" view of science - the God's eye view, the view from nowhere - actually depends on subjective capacities (conceptualization, measurement, mathematical reasoning) that have been systematically hidden or bracketed. The subject is constitutively necessary for the objective picture but gets erased from the picture itself.

In quantum mechanics specifically:

This erasure becomes impossible to maintain. The measurement apparatus, the observer's choice of what to measure, the collapse of the wave function - the subject keeps reappearing because quantum phenomena are inherently relational. You can't bracket out the conditions of observation the way classical physics was able to.

Michel Bitbol's "veiled subject":

Bitbol argues that modern science achieved its success precisely by veiling the transcendental subject - making it seem like we're describing nature "as it is in itself." But this veiling has costs: we forget that all such knowledge is contingent on the structures of possible experience. Quantum mechanics has forced this forgotten 'bracketing' back into view.

The "transpersonal" qualifier is important:

The transpersonal subject is not solipsistic - it is not 'the individual consciousness creating reality'. Rather, it's the shared structures of rationality, perception, and measurement that together constitute the conditions for any subject. Accordingly, the 'veiled subject' is transcendental/transpersonal, not psychological. -

Are there any good reasons for manned spaceflight?warp drive/wormhole/gravity drive type of thin — AmadeusD

I respectifully think a lot of these ideas are science fiction. Which has, after all, seeped into the culture through nearly a century of cinematic memes. But if the Earth can't even get it together to agree to a treaty to prevent climate catastrophe, what are the odds of pulling together the kind of massive global effort required for planetary expansion. All the people spruking it - Bezos and Musk, mainly - are the top 1% of the top 1%, and they stand also to be the chief finacial beneficiaries of the whole endeavour, such as it is. -

Are there any good reasons for manned spaceflight?Can i put to those people: The long stretch between the wheel and the engine, the engine and the aeroplane, and the aeroplane and the Moon landing. — AmadeusD

Yeah, I'm one. The analogy doesn't hold, though. Mars is a possibility, as it is within some kind of striking distance. But even so, the problems involved in travelling there, let alone setting up habitable environments, are enormous.

But anything outside the solar system is another matter altogether. The times and distances involved are unthinkably huge. The nearest star system, Proxima Centauri, is 4.25 light years away and any kind of travel that covers those distances would take millions of years. That is 40 trillion kilometres, give or take. To give a sense of scale: even at 100,000 km/h (far faster than any crewed spacecraft has ever flown), the trip would take roughly 45 million years.

And even if propulsion and life-support challenges could somehow be overcome, human interstellar travel faces a fundamental biological barrier in the form of radiation exposure. Beyond Earth’s magnetosphere and the Sun’s heliosphere — crews would be continuously bombarded by high-energy galactic cosmic rays and episodic solar particle events. These particles penetrate most conventional shielding, generate secondary radiation within spacecraft materials, and accumulate irreversible damage to DNA, nervous tissue, and immune systems over time. Measured radiation doses on a Mars trajectory already approach the upper limits considered acceptable for astronaut careers; over interstellar timescales of decades or centuries the cumulative exposure would almost certainly exceed survivable thresholds. In this sense, radiation is not merely an engineering inconvenience but a hard biological constraint on human deep-space travel.

There was an ambitious idea to send ultra-light computer-powered systems to Proxima Centauri using laser-guided sails, Breakhrough Starshot. It sounds at least feasible, if not actually possible. But even that is effectively on hold. -

Cosmos Created MindMy definition of Energy : A. not a tangible material substance — Gnomon

The point remains that energy is an abstract but universal, constant, and predictable property of matter - precisely measurable to minute degrees of accuracy. It is not a material substance, but the matter-energy equivalence has been demonstrated in Einstein’s famous equation e=mc2. Ghosts are in no way measurable or observable whatever. So the comparison is fatuous.

All due respect, I don’t think you demonstrate understanding of the sources you’re quoting. You’re still grasping after the idea of a ‘mysterious substance that does stuff’ - some cross between information and energy - so you will gather up definitions and catch-phrases that you think can be pressed into this mould. Not interested in pursuing this further. -

About TimeAlso, bear in mind that Kant has more to say about his religious philosophy, in his Critique of Practical Reason (and also, I think, his Religion within the Limits of Pure Reason), which I haven't studied, and only have a superficial acquaintance with.

I asked claude.ai to provide a synopsis of my posts on the Forum, which it did in about 3.1 seconds. It pointed out that:

3. Platonism & Mathematical Realism

You're interested in Platonic forms, mathematical platonism, and the "unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics." You argue that formal concepts exist independently of individual minds and reflect an intelligible order in the cosmos.

So I have to take ownership of this, as I've so often argued it and I do believe it. -

Are there any good reasons for manned spaceflight?SpaceX has made advances in the re-usability of the rockets, which wass quite a leap. — ssu

That, I have to agree with. SpaceX is clearly an astoundingly competent company, Those re-landing rockets are an engineering marvel, no doubt about that. StarLink is also an extremely clever company with global impact. Up until Elon Musk turned out to be such a complete a***hole, I was really impressed with him. It's depressing to see such obvious brilliance yoked to such malevolent politics.

--

Yet obviously when there's poverty, many can obviously make the question that "Why are we spending money in things like space programs, when there are so many people that are poor?" — ssu

Silicon Valley has given a lot of money to the effective altruism community, which has provided scholarly legitimacy to tech billionaires’ hobbyhorses. Effective altruists encourage the use of reason and data for making philanthropic decisions, but Becker highlights how some of their most influential thinkers have come up with truly bizarre “longtermist” calculations by multiplying minuscule probabilities of averting a hypothetical cataclysm with gargantuan estimates of “future humans” saved.

One prominent paper concluded that $100 spent on A.I. safety saves one trillion future lives — making it “far more” valuable “than the near-future benefits” of distributing anti-malarial bed nets. “For a strong longtermist,” Becker writes, “investing in a Silicon Valley A.I. safety company is a more worthwhile humanitarian endeavor than saving lives in the tropics.” — NY Times Review -

Cosmos Created MindAnd it's those philosophically-inferred relationships that I refer to as Causation, and use physical Energy as an analogy for how the world works on multiple levels. Including Ontology and Epistemology. However, I don't mean that physical Energy is the same thing as metaphysical Causation. — Gnomon

But that's what I mean. In our previous exchange about energy:

My point was simply that Energy is not a tangible material substance, but a postulated immaterial causal force (similar to electric potential) that can have detectable (actual) effects in the real world : similar to the spiritual belief in ghosts. — Gnomon

I'm afraid this is a terrible analogy (and many others would describe it much more harshly).

I tried to point out that in physics, 'energy' has a precise definition and meaning, which I think you were disregarding, in order to use the term in a particular way to suit your polemical framework. I think Boundless was making the same point (and he's certainly not a scientific materialist.)

I'm sympathetic to your orientation, and also appreciate the fact that you're not an antagonistic contributor, both of which are plusses. But interpretive integrity requires a certain amount of respect for definitions and facts. And here we're often discussing and debating many difficult ideas which are very easy to misinterpret or misconstrue. -

Are there any good reasons for manned spaceflight?How things are going, it is extremely likely that the last astronaut that walked on the Moon may die of old age since we go back to the Moon, if we go anymore there. Going to Mars is even more questionable. Actually here Neil Armstrong (first on the moon) and Paul Ciernan (last on the moon) are asked that question on the future of manned space flight. Now both are dead and nobody has gone to the moon back. I think the youngest Apollo astronaut that walked on the moon is now 90 years of age. — ssu

That was a good and persuasive post, and I acknowledge the importance of space technology for scientific exploration and for the unintended benefits it has provided.

But I have become sceptical of the 'colonize Mars' narrative. There are plenty of articles out there on the huge physical impediments to doing that, let alone the economic and political barriers. There's also the fact that in the US at least, the ultra-wealthy tech oligarchs (Musk, Bezos, etc) are positioning themselves as the sole providers (and therefore beneficiearies) of the technologies required for these fantastical ideas. This article by Adam Becker, who is a reputable science author and journalist, spells it out particularly well. (His book More Everything Forever, is a powerful takedown of the tech bros visions.)

Mars is too inhospitable to allow a million people to live there anytime remotely soon, if ever. The gravity is too low, the radiation is too high, there’s no air, and the Martian dirt is filled with poison. There’s no plausible way around these problems, and that’s not even all of them. Nor does the idea of Mars as a lifeboat for humanity make sense: even after an extinction event like an asteroid strike, Earth would still be more habitable than Mars. Mammals survived the asteroid strike that killed the dinosaurs, but no mammals could survive unprotected on Mars today.

Putting all of that aside, if Musk somehow did put a colony on Mars, it would be wholly dependent on his company, SpaceX, for supplies. That’s one feature that tech oligarchs’ fantasies have in common: they all involve billionaires holding total control over the rest of us. — Adam Becker

Jezz Bezos, on the other hand, wants 'a trillion people living in a fleet of giant cylindrical space stations with interior areas bigger than Manhattan.' Also fantasy, plainly.

Recall that fantastic Tom Hanks movie about Apollo 13, that almost crash-landed on the Moon after an engine problem, and which required incredibly adroit improvisation and trouble-shooting with what we would now consider very primitive computer technology. That's the kind of pioneering spirit that made NASA great in the day. Whereas Musk and Bezos owe more to Star Wars than to down-home technological smarts.

This idea that we have to 'colonize other planets' to 'escape Earth' is a sci-fi fantasy. We have a perfect starship, one capable of supporting billions of humans for hundreds of milions of years. But it's dangerously over-heated, resource-depleted, and environmentally threatened. That's where all the technology and political savvy ought to be directed - to maintaining Spaceship Earth. -

About TimeGetting the sense for what 'empirical realism' means for Kant is not a wholesale rejection of Descartes. — Paine

I agree. It's not a wholesale rejection, but a correction.

I've also noticed that Edmund Husserl similarly commented on the mistake Descartes makes in respect of 'res cogitans'. He sees the cogito and the turn to first-person evidence as the genuine origin of transcendental philosophy (including his own). His criticism is internal: Descartes discovers transcendental subjectivity but then reinterprets it in the old metaphysical grammar of substances, turning it into something quasi-objective. Then follows all of the confused questions about what 'it' is etc. -

About TimeVery roughly, for me it shows up as (1) less compulsion to define or secure a fixed identity, (2) more tolerance for uncertainty and contingency, and (3) a slightly quieter self-preoccupation in everyday experience. Hard to argue for — more something noticed over time.

-

About TimeKant never refers to the transcendental subject or transcendental ego

— Wayfarer

He does refer to it, albeit in as a source of misunderstanding — Paine

Thanks for those passages, they are right on point.

So he refers to the transcendental subject as something that can't be referred to! Which was the point I was trying to make.

Kant’s point is precisely that the “transcendental subject = x” is not something that can be known, described, or treated as an object at all. It is a formal condition of representation, not a determinate entity. So yes — he refers to it only in order to show why it cannot properly be referred to as an object of knowledge. Questions about its constitution, origin, or ontological status are, for Kant, literally empty of meaning (i.e. 'what is it?' presupposes an 'it'.)

Recall this passage from the related thread about MIchel Bitbol and phenomenology:

Bitbol argues in Is Consciousness Primary? (that) consciousness is not an object among objects, nor a property waiting to be discovered by neuroscience. It is not among the phenomena given to examination by sense–data or empirical observation. If we know what consciousness is, it is because we ourselves are conscious beings, not because it is something we encounter. — Wayfarer

It is precisely the tendency to reify (=make into something) the subject (or observer) that bedevils so much of the discourse about consciousness. First Descartes designates it res cogitans, 'thinking thing'. Then natural philosophy comes along and negates any such idea as self contradictory and incoherent, leading to philosophical materialism (=sole reality of res extensa). But Kant has already diagnosed and ameliorated these mistakes in this analysis.

I think learning to accept and live with the elusive nature of the self/subject/'I' is a fundamental life lesson. -

About TimeGood as starting points and good to avoid dogmatisms but they can't structurally be 'the last world'. They seem to point to some conclusion and just stop before asserting it. In other words, these approaches seem to point beyond themselves naturally. — boundless

I think you meant ‘last word’ (although it’s an interesting slip). But I agree - they’re not ‘the last word’ in the sense of conveying the absolute truth. They’re a starting point, not a conclusion.

Hope all goes well, I too will be taking a few days out. -

Cosmos Created MindClearly, idealism (i.e. 'mind-dependency') is an anthropocentric fallacy and contrary to the Copernican Principle — 180 Proof

But you never demonstrate a grasp of the implications of philosophical idealism. In the various OPs and essays where I present it, idealism is closely linked to what is called in modern philosophy constructivism: the understanding that the brain synthesises sensory input and conceptual structures to generate what we ordinarily take to be a fully external world. That is not anthropocentrism, nor does it imply that the universe depends on human minds in order to exist. It is an acknowledgment of the nature of knowledge, and, more to the point, the reality of being.

I started listening to the video, and the very first sentence already gives the game away: “It seems that reality somehow waits for awareness before deciding what it is.”

“Waiting” is an intentional predicate. It presupposes an agent that entertains a state of anticipation or suspension. But no serious account of observation — in either physics or philosophy — is committed to anything like that. Introducing this language at the outset inserts a straw man into the presentation. The follow-up claim that “physics dismantles this idea” continues the same. Physics does nothing of the kind; 'dismantling is the aim of a presentation about physics, which in turn always requires interpretation. Phrases like “the universe constantly measures itself” are further examples of a metaphor doing illicit conceptual work.

There is also equivocation in the use of the word 'observer'. Sometimes it denotes a physical interaction system (detectors, environments, particles); sometimes it implicitly refers to a conscious subject. Showing that decoherence does not require a conscious observer in the first sense does nothing to address the second sense. The two uses of the term operate at different explanatory levels.

Finally, look closely at the channel itself: joined Nov 2025, a stream of 6-minute videos comprising computer-generated images with AI voiceovers, driven by a creator with a clear agenda. Someone selected the prompts, framed the claims, and published the material. In other words, there is very definitely an observer — namely the author of those materials. Without him (or her), they wouldn’t exist. :-) -

Cosmos Created Minddefinitions specifically tailored to the subject matter. — Gnomon

Discussion is one thing, but re-definition in support of an argument is another. 'Everyone has a right to their own opinions, but not to their own facts' ~ Daniel Patrick Moynihan. -

Michel Bitbol: The Primacy of ConsciousnessMy proposed second installment on Michel Bitbol was rejected by Philosophy Today. No reason given, but maybe because it's too specialised a subject matter, Bitbol's philosophy of quantum physics. But anyone interested can access it here ('friend link', ought not to require registration.)

-

About TimeNote that if, instead, you say that the transcendental subject is a 'pragmatic model' used to 'make sense' of the world without asserting that it is 'real', then you imply a non-dualist view (i.e. the very distinction of 'subject-object' is provisional). In these kinds of view, there is no need to explain how the subject came into existence. It is, after all, an useful 'map' at best. — boundless

Kant never refers to the transcendental subject or transcendental ego. That comes with later philosophers. But also, notice that in singling out the subject as an individual being, you're already treating this as an object of thought. That is what I mean by taking an "outside view".

What seems to be driving the worry you keep returning to is not so much a disagreement about Kant but a discomfort with contingency itself — the idea that the conditions under which a world appears are not grounded in something further, necessary, or metaphysically self-explaining or self-existent.

What you keep coming back to is

-

1. The transcendental subject is a condition of intelligibility.

2. But if it is contingent, it must have an explanation.

3. If it has an explanation, there must be something beyond it.

4. Therefore transcendental idealism is incomplete or unstable.

This is,preciselysomething like 'the Cartesian anxiety'. And perhaps, now, the 'useful map' analogy is a good one. In presenting this OP, I didn't set out to offer a 'theory of everything'. Really the point is to call out the naturalistic tendency to treat the human as just another object — a phenomenon among phenomena — fully explicable in scientific terms. This looses sight of the way that the mind grounds the scientific perspective, and then forgets or denies that it has (which is the 'blind spot of science' in a nutshell).

The point is not to replace scientific realism with something else, but to recall that the very intelligibility of scientific realism already presupposes what it cannot itself objectify: the standpoint of the embodied mind. So I'm not presenting it as 'the answer' but as a kind of open-ness or aporia. -

About TimeI think the main difference between Plato and Kant, is that Kant denies the human intellect direct access to the noumenon as intelligible object. — Metaphysician Undercover

Agree with the contrast you’re drawing: Plato allows a form of direct intellectual apprehension of intelligible reality, whereas Kant denies that human cognition has any such unmediated access apart from sensible intuition structured by space and time.

But I will call out the language of “intelligible objects.” I think this is where a deep metaphysical confusion enters. Expressions like “objects of thought” or “intelligible objects” (pace Augustine) quietly import the grammar of perception into a domain where it no longer belongs. They encourage us to imagine that understanding is a kind of inner seeing of a special type of thing. I'm of the firm view that the expression 'object' in 'intelligible object' is metaphorical. (And then, the denial that there are such 'objects' is the mother of all nominalism. But that is for another thread.)

But to 'grasp a form' is not to encounter an object at all. It is an intellectual act — a way of discerning meaning, structure, or necessity — not the perception of something standing over against a subject. Once we start reifying intelligibility into “things,” we generate exactly the kind of pseudo-problems that Kant was trying to dissolve. -

About TimeI think @Joshs previous comment (above your reply to me) holds, I hope that what I've been arguing so far conforms with it.

the 'transcendental idealist' takes the 'transcendental subject' as being an individual sentient (or rational*) being. — boundless

Here, you are treating the transcendental subject as if it were an entity that could itself be viewed from an external standpoint and compared with a “world without it.” But the whole point of the transcendental analysis is that there is no such standpoint. The subject here is not a being in the world, but the condition under which anything can appear as world. So asking how the world would be “without reference to it,” or how it “comes into existence,” already presupposes what the analysis rules out.

the transcendental idealist wants to deny that "the world without reference to any sentient/rational being" has any intelligibility and is completely unknowable even in principle. — boundless

And what world would that be? Presumably, the earth prior to the evolution of h.sapiens . But then, you're conflating the empirical and transcendental again. Notice that even to name or consider 'the world without any sentient/rational being' already introduces the very perspective that you are at the same time presuming is absent.

I totally get that this is not an easy thing to internalise, because we are so habituated to treating time, space, and objectivity as simply “out there.” Seeing them instead as conditions of intelligibility rather than as objects of description requires a genuine shift in perspective, a kind of gestalt shift. -

About TimeA note to clarify my view of what is meant by the 'in itself': it designates whatever has *not* entered 'the machinery and the manufactury of the brain' (to quote Schopenhauer.) Put another way: an object considered from no perspective.

You might be thinking of an object in the absence of any perspective, but even thinking of it requires either imagining it or naming it, both of which are mental operations.

This is why I have said previously that the ‘unobserved object’ neither exists nor does not exist — not because it is unreal, but because either claim already presupposes a standpoint from which it can be meaningfully predicated. To say 'it exists' is to predicate something of it when it literally 'hasn't entered your mind'. To say 'it doesn't exist' likewise already situates the object as something, the existence of which can be negated. So the 'in itself' is neither - in fact, not even a 'ding'! Just the 'in itself'.

(Again, the noumenon and the ding an sich are different in Kant's philosophy but they are often conflated, even by him.

Noumenon means literally 'object of nous' (Greek term for 'intellect'). In Platonist philosophy, the noumenon is the intelligible form of a particular. Kant rejects the Platonist view, and treats the noumenon primarily as a limiting concept — the idea of an object considered apart from sensible intuition — not as something we can positively know. And it’s worth remembering that Kant’s early inaugural dissertation already engages directly with the Platonic sensible/intelligible distinction.

The 'ding an sich' is not the same concept although as noted often treated as if it were. The ‘thing in itself’ designates whatever a thing may be independently of the conditions under which it appears to us. It is not an intelligible object we could know or describe, but precisely what cannot be brought under any standpoint or predicates at all.)

In relation to time, then: whatever we think exists, or might exist, is already implicitly located in time and space. Even the theoretical abstractions of modern physics (like virtual particles) are temporally, if ephemerally, existent. As Kant points out, in order to conceive of anything as a thing, it must be located in time and space which provide the structural conditions that underlie all empirical existence - the 'framework of empirical cognition', you might say. But because these ‘pure intuitions’ are so deeply embedded in our consciousness, we fail to recognise that the mind itself is their source. We think we are looking at them, when in fact we are looking through them, at the objects disclosed within them. -

About TimeIt's not a contradiction at all.

If there is, it is utterly independent of our perceptions and consciousness — Janus

Note the use of “is” and "it" here — “if there is X,” “if there is something unknown.” In designating it as a something, the grammar is already treating it as a determinate entity, when the whole point of the discussion is precisely that it is not even a thing in that sense. (In fact, this is where I think Kant errs in the expression 'ding an sich', 'thing-in-itself'. I think it would be better left as simply 'the in itself'.)

The phrase “in itself” is not meant to name a hidden object standing behind appearances, but to mark a limit: the point at which our concepts, predicates, and categories no longer legitimately apply. Once we start saying, of the in itself, that “it exists,” “it is independent,” “it has properties,” we have already introduced the very conceptual determinations that the notion of the in-itself was supposed to suspend. Remember this was Kant's argument against dogmatism (although I know you think that Kant was dogmatic.) But it should engender a genuine sense of not knowing.

That is why there is no contradiction in saying, on the one hand, that what reality is in itself lies beyond our conceptual and sensory reach, and on the other hand, that we cannot meaningfully predicate independence, existence, or non-existence of it. The first is a negative or limiting claim about the scope of cognition; the second is a refusal to reify that limit into a metaphysical object, a mysterious 'thing behind the thing.'

To insist that “if there is an in-itself, then it must be utterly independent” is already to assume the very issue under question — namely, that reality must be a kind of thing standing over against a mind, describable in abstraction from the conditions under which anything becomes intelligible at all.

None of this commits me to phenomenalism or to denying a shared world. We plainly inhabit a common world structured by stable regularities, constraints, resistance, error and correction. But those features belong to the world as it is disclosed within experience and inquiry, not to a metaphysical description of what reality supposedly is “in itself” apart from any standpoint whatsoever.

The deeper point is simply this: we are not outside reality looking in. We are participants within it. Treating the in-itself as a hidden object that either exists or does not exist already presupposes a spectator standpoint that the argument is calling into question.

Glad we have some points of agreement here and I appreciate the way you’ve framed this.

I agree entirely that something like a limiting or grounding function is logically indispensable. If we remove the idea that our experience is constrained by something not reducible to our beliefs or constructions, then reason, error, correction, and a shared world really do start to collapse. In that sense, I also agree that simply denying the “in itself” leads to incoherence.

Where I still want to be careful is about sliding from that logical indispensability to an ontological claim that what plays this limiting role therefore exists independently as some kind of determinate something — even if we immediately say it is unknowable or indefinable. My worry is that this quietly reintroduces the very reification the limit-concept was meant to address.

I’m not saying there’s a hidden thing behind the world that we can’t access. I’m saying that the fact we’re always inside reality — participating in it rather than standing outside it — means that our ways of describing it are never final or complete. Reality keeps pushing back on our concepts and forcing revision, but that doesn’t mean there’s a separate metaphysical object called “the in-itself.” The limit shows up in the openness and corrigibility of our own understanding, not as a mysterious thing beyond it.

So I’m not trying to remove the limit, but to interpret it differently: not as a hidden entity or substrate standing apart from us, but as a structural feature of our participation in reality — the fact that conceptual determination never closes upon itself, that experience is always constrained and corrigible without being exhaustively capturable in metaphysical predicates.

On that reading, reason, language, science, and intersubjective objectivity remain entirely intact. What drops out is only the picture of a fully observer-external reality that could, even in principle, be described as it is “in itself” from nowhere in particular. That seems to me a modest but important shift rather than a radical one.

With that, I offer another quote from the irascible but brilliant Arthur Schopenhauer, which I think makes the point that I was trying to press earlier, about how cogniive science validates aspects of philosophical idealism. The second sentence, in particular:

All that is objective, extended, active—that is to say, all that is material—is regarded by materialism as affording so solid a basis for its explanation, that a reduction of everything to this can leave nothing to be desired (especially if in ultimate analysis this reduction should resolve itself into action and reaction i.e. physics). But ...all this is given indirectly and in the highest degree determined, and is therefore merely a relatively present object, for it has passed through the machinery and manufactory of the brain, and has thus come under the forms of space, time and causality, by means of which it is first presented to us as extended in space and active in time. — Schopenhauer

And with that, I've said enough already, I need to log out for a few days to return to a writing project which is languishing for want of concentration. But thanks for those last questions and clarifications, I think the discussion has moved along. :pray: -

InfinityThe kind of thought that was subject of an excellent 2008 BBC documentary, Dangerous Knowledge.

-

About TimeThe quantum realm is so minute that the measuring tools we use to monitor the quantum state affect the state itself. Non-quantum measurement is like rolling a ping pong ball at a bowling ball. We bounce the ping pong ball off, then measure the velocity that the ball comes back to determine how solid the bowling ball is. The ping pong ball is rolled to not affect the movement of the bowling ball. — Philosophim

Not so:

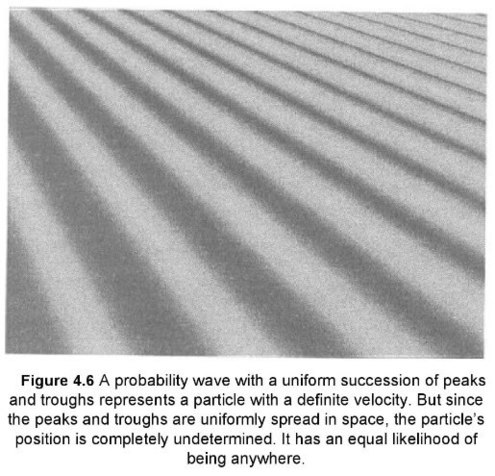

The explanation of uncertainty as arising through the unavoidable disturbance caused by the measurement process has provided physicists with a useful intuitive guide… . However, it can also be misleading. It may give the impression that uncertainty arises only when we lumbering experimenters meddle with things. This is not true. Uncertainty is built into the wave structure of quantum mechanics and exists whether or not we carry out some clumsy measurement. As an example, take a look at a particularly simple probability wave for a particle, the analog of a gently rolling ocean wave, shown in Figure 4.6.

Since the peaks are all uniformly moving to the right, you might guess that this wave describes a particle moving with the velocity of the wave peaks; experiments confirm that supposition. But where is the particle? Since the wave is uniformly spread throughout space, there is no way for us to say that the electron is here or there. When measured, it literally could be found anywhere. So while we know precisely how fast the particle is moving, there is huge uncertainty about its position. And as you see, this conclusion does not depend on our disturbing the particle. We never touched it. Instead, it relies on a basic feature of waves: they can be spread out. — Brian Greene, The Fabric of the Cosmos

There is a need to know the exact location and velocity of every electron circling an atom, and yet we don't have the tooling to get that — Philosophim

I'm sorry, but you're not seeing the real problem. The point of the uncertainty principle is that it's not a matter of 'tooling'. The uncertainty is genuine, as Brian Greene says above - a matter of principle. It is also true that scientific realists including Sir Roger Penrose don't accept this saying that there must be a better theory that hasn't been discovered yet. But I think that is far from a majority opinion. I acknowledge I'm not a physicist, but those references I mentioned (plus the Brian Greene one) do support what I'm saying.

But the issue is, you can't stipulate anything about the 'independent thing' without bringing the mind to bear upon it.

— Wayfarer

Barring one thing: That it is independent. Meaning you are saying it exists apart from your observation. How? Who knows really. That's the definition of true independence. It does not depend in any way on your comprehension of it. You know it can exist in a way based on your tested and confirmed model. But how does it behave apart from that model? At that point, you can glean certain qualitative logic that necessarily must be from the working model. One being, "That is independent". Meaning it exists apart from observation. How exactly? Who knows. Its the "Thing in itself" problem from Kant. And it is a fascinating topic. I like your exploration of it here. My point is that if it is not independent, what does that logically mean? Does that break our current model use, our definition of observer, and everything we comprehend? It would seem to. Maybe it doesn't, and I was curious if you had given it thought and could propose what that would be like. — Philosophim

I agree that this lands us very close to the “thing in itself” problem — but my own way of thinking about it probably leans more towards Buddhism.

What I mean is this: the “in itself” is what lies beyond our conceptual and sensory reach. It is not just unknown in practice; it is unknowable in principle insofar as any determination already brings the mind’s discriminations to bear. Even to say “it exists independently” is already to ascribe an ontological predicate to what is supposed to lie beyond all predication.

From that point of view, saying that the 'in-itself exists' is already a kind of over-specification — but saying that it does not exist is equally a mistake. Both moves bring in conceptual determinations into what is precisely not available to conceptual determination. We 'have something in mind'. That’s the sense in which 'it' is neither existent nor non-existent: not as a mysterious third thing, but because the existence / non-existence distinction itself belongs to the world as it is articulated for us.

So when you say “barring one thing: that it is independent,” I would hold off on that — not because I think the world collapses into subjectivism (ceases to exist outside my particular mind), but because “independence,” taken as an claim about reality in itself, is already a conceptual construction. What we actually encounter is constraint, resistance, regularity, surprise — all within experience and modelling. Independence as such is an abstraction we draw from that, not something we can meaningfully attribute to what lies beyond all possible description.

None of this breaks scientific models or the practical notion of an observer. Science continues exactly as before, operating perfectly well within the conventional domain of determinate objects, measurements, and laws. The point is only that when we try to step outside that domain and make ultimate claims about what reality is “in itself,” our concepts outrun their legitimate scope.

Bottom line: reality itself is not something we're outside of or apart from. We are participants in it, not simply observers on the outside of it. And that points towards an existential stance or way-of-being. -

About TimeThe distinction made between a realm of becoming and the realm of eternity in early Greek thought is an interesting frame to consider.

Change becomes the most difficult thing to talk about. — Paine

Yes — that distinction really does go back to Parmenides, for whom 'the Real' can’t change without becoming unintelligible, which is why becoming is relegated to the realm of appearance. Plato and Aristotle both respond by trying, in different ways, to show how something can remain the same while still genuinely changing. This was the origin of much of Aristotle's metaphysics of universals.

There’s also an interesting modern echo in Andrie Linde’s point that a purely observer-independent picture of the universe tends toward a kind of thermodynamic “deadness,” where time and becoming drop out of the equations in quantum cosmology. Meaningful change only manifests relative to observers in non-equilibrium conditions - 'an observer with a clock, and the rest of the Universe', as he puts it. It feels like a contemporary version of the same old tension between being and becoming (see this interview.)

The independent existent we are measuring, does not overlook the role of the observing mind. — Philosophim

But it does! This is the basis of the major arguments about 'observer dependency' in quantum physics. Here are some excerpts from an influential paper, which has really entered the realm of popular science, John Wheeler's Law without Law, something I've quoted previously. Here is Wheeler's gloss on the measurement problem in quantum physics, and it really shows in a few words, how it had called Einstein's lifelong belief in the 'mind independence of reality' into question:

The dependence of what is observed upon the choice of the experimental arrangement made Einstein unhappy. It conflicts with the view that the universe exists "out there" independent of all acts of observation. In contrast, Bohr stressed that we confront here an inescapable new feature of nature, to be welcomed because of the understanding it gives us. In struggling to make clear to Einstein the central point as he saw it, Bohr found himself forced to introduce the word "phenomenon". In today's words, Bohr's point - and the central point of quantum theory - can be put into a simple sentence: "No elementary phenomenon is a phenomenon until it is a registered (observed) phenomenon".

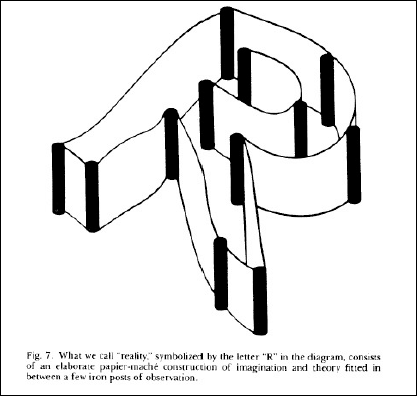

He also created this graphic to illustrate the point:

Caption reads: 'What we consider to be ‘reality’, symbolised by the letter R in the diagram, consists of an elaborate paper maché construction of imagination and theory fitted between a few iron posts of observation."

Notice this - the 'iron posts' are observations and measurements. But the shape of the R itself is a 'paper maché construction of imagination and theory'. That is what I mean by the way 'mind constructs reality'.

All this is elaborated in such books as Manjit Kumar. Quantum: Einstein, Bohr, and the Great Debate About the Nature of Reality. London: Icon Books; New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008 and David Lindley - Uncertainty: Einstein, Heisenberg, Bohr, and the Struggle for the Soul of Science. New York: Anchor Books/Random House, 2008. They make the centrality of the question of the 'mind-independence of reality' is central to these debates.

You can absolutely logically claim that if observers weren't there, the measurements that they invented in themselves would not exist. But you haven't proven that what is concluded inside of the framework itself, that there is change which independently exists of our measurement, isn't necessary for the framework to work. That is why it is not an assumption that if you remove the measurement, that the independent thing being measured suddenly disappears. — Philosophim

But the issue is, you can't stipulate anything about the 'independent thing' without bringing the mind to bear upon it. We know a lot about the early universe, before h.sapiens evolved, from cosmological science, geology and so on. But all of that is still structured within the framework the mind provides. You might say it was 'there all along' or 'there anyway' - but 'there' and 'anyway' are what the observer brings to the picture. This is what I mean by saying that there being an observer, nothing exists - not that does not exist, but neither does it exist, because there is no 'it'. Yes, when we discover 'it', we learn that it was there all along - but outside that framework, what is 'it'?

We don't notice that we're 'bringing the mind to bear' because that is the way that naturalism frames knowledge. There's the subject/observer, here, and the object/target, there, and never the twain shall meet.

I notice that you haven't actually commented on any of the philosophical arguments presented in the original post. I suggest that this is because you instinctively interpret the question through the frame of scientific realism. This is it intended as a pejorative statement, but as a way of understanding what the debate is about. Scientific realism is based on conviction of the reality of the observed world, and to question it is really a difficult thing to do. -

About TimeSize", "weight", etc., are not "the object", those terms refer to a specific feature, a property of the supposed object, and strictly speaking it is that specific property which is measured, not the object. — Metaphysician Undercover

That’s actually on point. It’s very close to Bergson’s argument about clock time: what gets measured is not concrete duration itself, but an abstracted, spatialized parameter extracted for practical and mathematical purposes. Precision applies to the abstraction — not to the lived or concrete whole. But then, we substitute the abstract measurement for the lived sense of time.

You have to understand that the act of measurement assumes something is there independent of the measurer — Philosophim

I don’t think any of the sources I’m drawing on dispute that there is something to be measured. Of course measurement presupposes an independent reality — otherwise measurement would be meaningless. The point is not that we create what we measure, but that the act of measurement already involves an observer-relative framework of abstraction.

Distance does not disappear if no one measures it — but “distance in meters,” embedded in a metric geometry and operationalized by instruments and conventions, does not exist independently of those frameworks. Likewise with clock time. What exists is change, passage, becoming; what we measure is an abstracted parameter extracted from it.

The philosophical claim is simply that it does not follow from the existence of something independent to be measured that reality itself can be specified in wholly observer-independent terms. That further move is a metaphysical assumption, not something licensed by the practice of measurement itself. It overlooks //or rather takes for granted// the role of the observing mind.

I think there’s a deeper issue lurking here. Absent any perspective whatever, what could it even mean to say that something “exists”? To exist is to be this rather than that — to stand apart, to have determinacy, identity, and distinction. That act of discrimination is not supplied by the world in the abstract; it is enacted by cognitive systems.

Space and time are intrinsic to that discriminative capacity. Without spatial differentiation and temporal ordering, there could be no stable objects, no persistence, no comparison, no calculation — and therefore no measurement at all. Conscious awareness and intelligibility presuppose these structuring forms.

None of this denies that there is something there independently of us. The point is that what counts as an existent — as something identifiable, measurable, and meaningful — already presupposes a standpoint capable of making distinctions. Pure “observer-free existence” is not coherent; it is an abstraction that undercuts the very conditions that make existence intelligible in the first place.

Husserl makes a related point in Philosophy as a Rigorous Science: naturalism quietly assumes “nature” as already given and self-evident, instead of asking how nature becomes constituted as an objective domain in the first place. The intelligibility and measurability of the natural world presuppose structures of cognition that naturalism itself cannot account for without circularity.

That is a cognitive process: the way the mind “brings forth” or constructs the world that naturalism treats as its starting point. This used to be the territory of philosophical idealism, but in an important sense these insights have been increasingly validated by cognitive science. Cognitive science explores how the brain and mind actively structure what we take to be external reality. That does not deny that there is an external reality — but an external reality can only be real for a mind.

This is how mind is properly re-integrated into a universe that naturalism assumes is without one. -

About Time

I don’t want to give the impression that I doubt science’s capacity for extraordinary accuracy in the measurement of time (and distance). Atomic clocks measure time with astonishing precision. The philosophical point, however, is that the act of measurement itself cannot be regarded as truly independent of the observer who performs and interprets the measurement.

So what? might be the response. The point is that this quietly undermines the assumption that what is real independently of any observer can serve as the criterion for what truly exists. That move smuggles in a standpoint that no observer can actually occupy. It’s a subtle point — but also a modest one. It doesn't over-reach.

Where it does appear to be controversial is insofar as it calls into question the instinctive sense that the universe simply exists “just so,” wholly independent of — and prior to — any possible apprehension of it. But again, that is a philosophical observation, not an argument against science. It is an argument against drawing philosophical conclusions from naturalistic premises. -

About TimeIsn't the measurement (of time) objective? — Corvus

It is. If you read the OP as saying it isn’t, then you’re not reading it right. -

About TimeHey, thanks! Most appreciated. There’s nothing I really differ with there. Again, I’m not saying that ‘nothing exists’ sans observers. What this, and most of my arguments, are against, is the elimination of the observer - the pretence that through the perspective of science, we see the world as it truly is. And the almost invariable implication, we’re a ‘mere blip’ in the vastness of cosmic space and time. That is viewing ourselves “from the outside”, so to speak - treating the observer as another phenomenon. When in reality the observer is that to whom or to which phenomena appear. That, I take to be the lesson of phenomenology and its forbears.

Again, I’ve also been most impressed with a book I’ve mentioned before Mind and the Cosmic Order, Charles Pinter (Routledge 2021.) Pinter was a maths professor emeritus whose last book (and swansong) was about the intersection of philosophy and cognitive science. It was not much noticed in the philosophy profession as he had been a maths professor - which is a shame, because it’s a genuinely insightful book. His big idea is the way cognition (not only human cognition) organises experience by way of meaningful gestalts.

I’m also influenced by Aristotle - not by having studied him at length, because I wasn’t educated in ‘the Classics’. But I’ve absorbed it by cultural osmosis, so to speak, and also through my pursuit of comparative religion and philosophy. In the time I’ve been posting to forums, since around 2010, I’ve developed respect for Aristotelian Thomism, although without necessarily buying into the devotional commitments. But I’m very much in the overall mold of Platonism, again I think through cultural osmosis.

We know there is activity independent from the observer, and any activity requires the passage of time. — Metaphysician Undercover

“The observer knows there is activity independent from the observer”. He does indeed. -

Michel Bitbol: The Primacy of ConsciousnessThanks. I'm interested in this fragment from a review of the following book. (I acquired a copy, but it's very technical and specialised):

Husserl called his position "transcendental" phenomenology, and Tieszen makes sense of this by claiming that it can be seen as an extension of Kant's transcendental idealism. The act of cognition constitutes its content as objective. Once we recognize the distinctive givenness of essences in our experience, we can extend Kant's realism about empirical objects grounded in sensible intuition to a broader realism that encompasses objects grounded in categorial intuition, including mathematical objects.

The view is very much like what Kant has to say about empirical objects and empirical realism, except that now it is also applied to mathematical experience. On the object side of his analysis Husserl can still claim to be a kind of realist about mathematical objects, for mathematical objects are not our own ideas (p. 57f.).

This view, Tieszen points out, can preserve all the advantages of Platonism with none of its pitfalls. We can maintain that mathematical objects are mind-independent, self-subsistent and in every sense real, and we can also explain how we are cognitively related to them: they are invariants in our experience, given fulfillments of mathematical intentions. The evidence that justifies our mathematical knowledge is of the same kind as the evidence available for empirical knowledge claims: we are given these objects. And, since they are given, not subjectively constructed, fictionalism, conventionalism, and similar compromise views turn out to be unnecessarily permissive. The only twist we add to a Platonic realism is that ideal objects are transcendentally constituted.

We can evidently say, for example, that mathematical objects are mind-independent and unchanging, but now we always add that they are constituted in consciousness in this manner, or that they are constituted by consciousness as having this sense … . They are constituted in consciousness, nonarbitrarily, in such a way that it is unnecessary to their existence that there be expressions for them or that there ever be awareness of them. (p. 13). — Richard Tieszen, Phenomenology, Logic, and the Philosophy of Mathematics (Review)

My belief is that numbers, forms, and so on, are structures in consciousness, in a somewhat Kantian sense. Put very simply, if you ask me what 2 and 2 are, I am obligated to answer '4' - which doesn't say there is any such 'thing' as a number in some purported 'platonic space'. Counting is an act, and numbers represent those acts. So as acts, forms, ideas, etc are intrinsically dynamic, but also invariant.

(I haven't read Deleuze yet, although watched a very interesting video lecture on his 'registers', which, um, registered for me.)

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum